Kirk Hallahan

Inactive Publics: The

Forgotten Publics in

Public Relations*

ABSTRACT: By focusing on activism and its consequences, recent public relations theory has largely ignored inactive publics, that is, stakeholder groups that demonstrate low levels of knowl-edge and involvement in the organization or its products, ser-vices, candidates, or causes, but are important to an organization. This article examines the nature of inactive publics and proposes a model that locates inactive publics among five categories of publics along the dimensions of knowledge and involvement. The model provides a theoretically rich alternative for how public relations practitioners might conceptualize publics, a central con-cept in public relations theory and practice.

Kirk Hallahan is an assistant professor in the Department of Journalism and Technical Communication at Colorado State University.

In recent years, public relations theory has focused mostly on publics that are interested in and concerned about the activities of organiza-tions. Largely overlooked is the importance of groups that have only minimal motivation, ability, or opportunity to know about, talk about, or participate in efforts to influence the policies or practices of organizations. These forgotten constituencies can be referred to as inactive publics.

The field’s preoccupation with activism is well-grounded theoretically and well-founded because of the potential consequences of activist groups, which can

*This article is based on a Top Faculty Paper presented at the PRSA Educators Academy International Interdisciplinary Research Conference in June 1999 at College Park, MA. Public Relations Review,26(4):499 –515 Copyright © 2000 by Elsevier Science Inc.

directly and immediately threaten the organization’s goals or help to attain them. However, the assumption underlying contemporary theory focused around activ-ists is that the interests of organizations and publics are necessarily at odds with one another. The focus on activism, as manifested in issues management, for example, implies that individuals who constitute a public are sufficiently interested and equipped to think about problems, to engage in meaningful conversation with others, and to organize to take action. For example, normative models that suggest public relations is practiced ideally as two-way, symmetric communication pre-sume that publics are active participants and are both motivated and able to voice concerns through activities such as collaboration.1Similarly, situational theory is intended to serve as a predictor of activism, as measured in active information seeking and passive information processing.2Recent articles that draw on inter-personal communication, psychotherapy, and interorganizational communication similarly assume that organizations and publics must interact to form relation-ships.3

This article begins with a quite different set of assumptions from those that underlie much contemporary public relations theory. First, it assumes that not all public relations activities necessarily revolve around issues, disputes, or conflicts. Indeed, many public relations programs today merely involve building positive relationships. In such cases, differences between organizational interests and pub-lic needs might not exist or might be minimal at best.

Second, many organizational–public relationships can operate at an ex-tremely low level, that is, rank-in-file members of a public have only minimal knowledge and involvement in the policies and practices of an organization. More important, this minimum-level relationship suffices both parties. A richer, more intensive, more “meaningful” relationship might not be necessary. Indeed, orga-nizations might not have the financial, temporal, or human resources to establish close relationships with everyone; meanwhile, members of inactive publics simply have other concerns.

Third, the prospect of establishing and maintaining minimal relationships with inactive publics pose a set of communication challenges that are quite differ-ent from interactions with highly active publics, where communications are often highly reactive, interactive, and sometimes confrontational. Such communications efforts require different strategies that public relations theorists must begin to address in a more coherent manner.4

DEFINING INACTIVE PUBLICS

One of the most conceptually troublesome notions in con-temporary public relations is the idea of a public. In its classical definition, public is reserved to describe groups that are actively involved in the discussion of a public issue. Publics, thus, are organized around issues. Dewey defined a public as a group of people who (1) face a similar problem, (2) recognize the problem exists, and (3) organize to do something about the problem. Blumer later offered a similar

nition of public as a group of people who are (1) confronted by an issue, (2) divided in their ideas about how to meet the issue, and (3) engaged in discussion about the issue.5

In contemporary public relations practice, this narrow definition of a public is largely ignored. Researchers and practitioners often use the term public when referring to a variety of other, closely related concepts. Public is used to refer to potential or actual audiences, that is, receivers of messages. Public also is used to describe segments, such as a market segment, that is, a group of people who share particular demographic, psychographic or geodemographic characteristics and thus are likely to behave or respond to organizational actions or messages in a similar way. With increased frequency, public is used to refer to communities, that is, groups drawn together by shared experiences, values, or symbols. Public also can be used synonymously with constituents, that is, groups (such as voters) that an organization serves and to whom the organization is ethically or legally responsi-ble.

The term is also used to denote stakeholders, that is, people who are impacted by the actions of an organization. In their three-stage model of issue development, Grunig and Repper (1992) illustrated the difficulty of nomenclature. In describing the first stage, the stakeholder stage, they wrote:

An organization has a relationship with stakeholders when the behavior of the organization or of the stakeholder has consequences on the other. Public relations should do formative research to scan the environment and the behav-ior of the organization to identify their consequences. Ongoing communica-tion with these stakeholders helps to build a stable, long-term relacommunica-tionship that manages conflict that may occur in the relationship.6

The authors explained that the second stage, the public stage, occurs when “stakeholders recognize one or more consequences of a problem and organize to do something about it or them.” Finally, they identified the issue stage, which is “not reached until publics organize and create issues out of the problems they perceive.” Grunig and Repper admitted only subtle differences between a stake-holder group and a public. In particular, stakestake-holders are passive: “Stakestake-holders who are or become more aware and active can be described as publics.”7 This inconsistency is troublesome because Grunig and Repper freely acknowledged that public relations initiatives are not limited to publics alone, that is, active groups, but can (and should) be directed to passive stakeholder groups as well.

One way to reconcile this problem is to define all groups to which public relations efforts are directed as publics, but to recognize that they differ in their levels of activity–passivity. Inactive publics largely meet the definition of stakehold-ers,8but no assumption is necessarily made that they recognize their stakeholder role. This approach is considerably more straightforward and subtly extracts the definition of public from a discursive framework, that is, a requirement that a concerted interaction among individuals is necessary for a public to exist.9Thus a public might be defined simply as a group with which an organization wishes to

establish and maintain a relationship. Alternatively, a public can be defined as a group of people who relate to an organization, who demonstrate varying degrees of activity–passivity, and who might (or might not) interact with others concerning their relationship with the organization.

Inactive public, as defined here, is strikingly akin to the notion of a mass, which along with crowd and public constitute the three principal categories of social groups identified by Blumer. The noted sociologist distinguished a mass from a public by observing that a mass “merely consists of an aggregation of people who are separate, detached, anonymous” and who act in response to their own needs.10 A mass is characterized by very little interaction or communication, considerable homogeneity, and wide geographic dispersion. However, members of a mass are brought together by some common source of interest or attention. This might include, for example, the identity people share as citizens of a nation or the common stake they have in an organization. In this sense, a mass or an inactive public might be considered a symbolic community, a group of people who share a common set of symbols and experiences.11

A SOCIETY OF LOW-LEVEL RELATIONSHIPS

The inactive nature of the population in modern society has been recognized by sociologists, political theorists, and journalists. Theories of mass society, as first proposed by classical sociologists, suggest that individuals have become atomized members of society through the division of labor and estrange-ment from others. In mass society, people are thrust into a social system dramat-ically different from the communal structure that characterized life before the rise of urbanization and industrialization.12

Lippmann was one of the first observers of the implications of these changes for communications and the political process. He observed that, by the 1920s, people no longer acted based on direct experience, but were dependent on sec-ondary information sources such as the mass media. Lippmann argued that people act based on the resulting “pictures inside our heads.”13Later, he suggested that the population in modern society had become a phantom public that was mostly disinterested in public affairs and quite content to delegate decision making about issues to experts.14Subsequent writers have lamented the decline in the robustness of public discussion and debate.15

Significantly, inactivity should not be confused with deliberate manipulation or control by powerful forces within society, as critical theorists suggest.16Indeed, inactivity is not equivalent to a lack or capability or concern for others by people in society. Research in the past three decades suggests that audiences are not passive, but are active processors of information. People construct their own meaning from mediated messages and other forms of communication and put information in the context of their own lives.17

In large measure, the inactivity characteristic of mass publics today can be

explained as a function of the large, complex, interdependent nature of modern society. Today, people juggle a variety of different activities and concerns in their daily lives. Cognitive psychologists have characterized humans as “cognitive mi-sers,”18who process information only as required to cope with information over-load.19 People can cope with only a limited number of problems or situations in their lives at one time. In the same way, the carrying capacity of public arenas to address social problems or issues is limited.20

As a result, people are selective about the issues in which they become involved or consider important. Individuals enter into deep relationships with only a handful of other individuals (spouses, significant others, friends) and only a few organizations or institutions (most notably, schools and employers). Yet as a matter of survival, they also enter into a wide range of secondary or tertiary relationships that are much more superficial and purposely limited in scope. Not all relationships are equally important; thus assumptions that public relations should treat every organizational-public relationship in the same way requires careful scrutiny.21

Resource dependency theory, for example, suggests that people enter into relationships in response to the need for resources.22In today’s industrial society, publics contract with large, complex organizations that provide services ranging from groceries to utilities. As long as those services are provided reliably and satisfactorily, and within a range of ethical expectations, there is no reason for many people to pay much attention to these organizations or desire a more in-depth relationship with the organization that provides them. The closing of gaps in expectations is one basis for dealing with issues, whereas the elimination of gaps in reliability and satisfaction is behind the recent total quality management move-ment in organizations.23

Social exchange theory suggests that people enter into relationships by analyzing costs versus benefits. People expect benefits to exceed costs, and people will withdraw from a relationship whenever perceived costs exceed benefits, based on their analysis of comparison levels.24 Under this socioeconomic approach to relationships, people have little incentive to change (or incur “switching costs”) unless the perceived costs significantly exceed the perceived benefits. Unless the problem is particularly important, or people are prompted to act by external actors, inertia can lead to indifference and inactivity or what might be termed routine behaviors.25

A TYPOLOGY OF PUBLICS

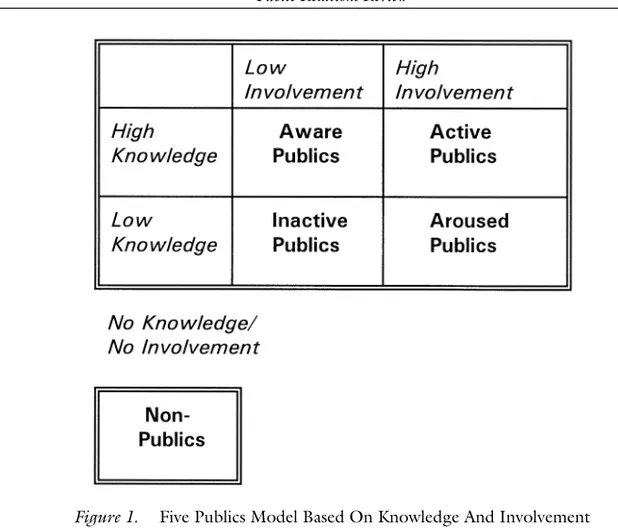

What defines inactive publics? An inactive public is theo-retically the opposite of an active public. An analysis of the behavioral literature suggests that two criteria are paramount in understanding the behaviors of indi-viduals and the groups they comprise: the knowledge that indiindi-viduals and groups hold about a particular topic and their involvement in the topic. The logical extension of this approach is to suggest a five-cell model that differentiates groups

exhibiting different combinations of high and low involvement and high and low knowledge, plus a provision for groups that exhibit virtually no knowledge nor involvement (Fig. 1). Significantly, this model builds up previous theorizing about publics in political science and extends and refines J. Grunig’s classification scheme for publics.26

Inactive Publics

Inactive publics are conceptualized here as groups com-posed of individuals who, as a whole, possess comparatively low levels of knowl-edge about an organization and low levels of involvement in its operations. Knowl-edge and involvement similarly can be operationalized in terms of the products, services, candidates, or causes provided or represented by an organization. Inactive publics generally are organization stakeholders who might or might not recognize the consequences for them of an organization’s actions. As a whole, members of inactive publics might be satisfied with the relationship that exists between them and an organization because the relationship meets their needs. Alternatively, members of inactive publics might believe it is not worthwhile to challenge the relationship or might take the relationship for granted without much consider-ation. Yet others might take a fatalistic position that nothing can be done to alter the situation.

Figure 1. Five Publics Model Based On Knowledge And Involvement Public Relations Review

Aroused Publics

Aroused publics share comparatively low levels of knowl-edge about an organization and its operations with inactive publics, but include people who have recognized a potential problem or issue. Their level of involve-ment is heightened. Their arousal can be prompted by several different factors: personal experience; media reports or advertising about a situation involving oth-ers with whom they identify; discussions with friends; or exposure to issue creation efforts by organizers for social movements, special interest groups, or political parties. The transformation of individuals from an inactive to an aroused state and, eventually, to an active state constitutes the limited focus of situational theory.

Aroused Publics

Aware publics include groups that might be knowledgeable generally about an organization or situation, even though its members might not be affected by it directly. Aware publics often include groups labeled by political scientists as attentive publics, that is, the stratum of society that is generally knowl-edgeable about the world (including public affairs) and serve as opinion leaders through their positions in society, education, or backgrounds.27These groups can include all-issue publics. Aware publics, in contrast to merely aroused publics, can be knowledgeable about an organization and or its activities and might be able to articulate the origins, processes, and consequences of potential issues. However, merely aware publics do not have a personal stake.

Active Publics

Active publics are composed of individuals who share both high involvement and high knowledge of an organization (or an issue) and thus are predisposed to monitor situations and to organize, if required. They clearly meet the traditional definition of a public set forth by Dewey and Blumer. Examples include the leaders of social movements and special interest groups as well as close followers who are willing to exert personal time and effort to effect change. Active publics often are directly involved in issue advocacy; might serve as missionaries for the cause; and might serve as representatives for a social movement, special interest group, or political party in interactions with an organization.

Nonpublics

Nonpublics, the default component in the model, are com-posed of individuals with no knowledge and no involvement whatsoever with an organization. However, once individuals attain any level of knowledge or involve-ment, they properly should be accorded inactive public status.

An Alternative Perspective on Publics

Others have suggested the potential value of reassessing the classification of publics used in the field. For example, Goldman and Theus

gested, based on their study of two healthcare organizations, the need for “another look at the accepted definitions of aware and active publics” and called for a redefinition of the terms as used in Grunig’s model.28

This model of publics departs from Grunig’s typology of active, aware, latent, and nonpublics in several ways. First, its purpose is to identify the different states in which groups and individuals might be found for purposes of an organi-zation initiating communications with them, rather than predicting the probability of an individual becoming aroused about or active on an issue. J. Grunig’s model in situational theory makes the presumption that activism is the ultimate result. Second, the model presented here incorporates, as antecedents, the general con-cepts of knowledge and involvement, rather than problem recognition, constraint recognition and involvement. In particular, the emphasis is on prior knowledge as a predictor of responses to communication efforts, rather than information gain (in the form of passive information processing or active information seeking) as an outcome.

Third, this model differentiates between inactive and aroused publics, which J. Grunig combines as latent publics. Latency to become active is proposed here to be a trait (vs. state) that can be found among individuals within any of these categories. Although an individual who is merely aware (high knowledge but low involvement) has the potential to move into the active category, individuals within the aroused category are more likely to become activists because their level of involvement has been activated, even though their knowledge might still be un-developed. Thus, the model suggests that heightened involvement or recognition of relevance is a prerequisite for knowledge acquisition leading to activism.

Fourth, the model reserves use of the term aware to mean knowledge, and thus suggests that knowledge about a problem is a necessary, but not sufficient, condition for an individual or group to become active. Activism requires both knowledge and involvement, unless aware publics are motivated by factors other their personal involvement in the issue itself, for example, power, greed, political duty, or professional responsibility. By recognizing that there are people who were merely aware of a problem or issue, it explicitly acknowledges the importance of third parties and third-party groups that are not addressed in J. Grunig’s model of publics or in situational theory.

Finally, the use of the term nonpublic here attempts to reconcile Grunig’s construct with the conceptual framework outlined here. Under Grunig’s original conceptualization,29 a nonpublic fails to meet Dewey’s definition of a public because it is not organized around an issue, and the actions of the organization have no consequences for the public, and vice versa. Yet, many nonpublics actually can have knowledge about an organization, product, service, candidate, or cause. This model specifies that only groups that have absolutely no knowledge and no involvement can be classified as nonpublics. In the segmentation of publics, orga-nizations can and probably will choose to ignore nonpublics. However, organiza-tions might also choose to ignore segments of inactive publics for a variety of reasons, such as a lack of resources.

KNOWLEDGE AND INVOLVEMENT AS CRITERIA FOR DEFINING PUBLICS

The rationale for defining publics along the two dimen-sions of knowledge and involvement is well grounded in recent research in social psychology and consumer behavior. These two constructs have been identified as important factors in learning, information processing and persuasion.

Knowledge, a variable related to ability, refers to beliefs and attitudes held in memory about a particular object, person, situation, or organization, based on everyday experience or formal education.30Beliefs involve what a person holds to be true; attitudes represent predispositions toward an object based on beliefs and values.31Knowledge is believed to organized in memory as associated networks of memory nodes32 or in hierarchical knowledge structures known as schemas.33 Experts on a particular topic, that is, individuals with well developed networks or schemas related to a particular topic, are believed to attend to messages more frequently and are able to make sense of them more readily than others.34

Expertise or familiarity, however, does not mean that information is pro-cessed more thoroughly. Individuals with high levels of knowledge can process information more efficiently and with less effort because they compare information to extant knowledge stored in memory to discern discrepancies, and then focus cognitive capacity on reconciling differences, that is, either reinterpreting the meaning of the message or altering extant knowledge when new or more credible information is obtained. Experts can be quite discriminating in making judgments about the validity of messages.

Novices, or individuals with low levels of extant knowledge, are at a disad-vantage in information processing. They are less likely to attend to messages with which they are not familiar and must exert more effort to make sense of informa-tion, such as identifying the appropriate schema where information fits. Individuals with low knowledge of a topic have difficulty placing information in context and often can miscomprehend information.35Novices are less discriminating and often will accept a wider range of arguments as being valid because they are less equipped to challenge the validity of claims.36

Involvement, a motivation variable, has been recognized as a distinct con-struct from knowledge and refers to the degree to which an individuals sees an object, person, situation, or organization as being personally relevant or having personal consequences.37 Mitchell described involvement as “an individual level, state variable that indicates the amount of arousal, interest or drive evoked by a particular stimulus or situation.”38

Although the involvement construct suffers from a variety of conceptualiza-tions,39 involvement has generated robust findings among researchers. The in-volvement construct was first conceived a half century ago by Sherif and Cantril40 and became a focus of applied communication research beginning with research on low-involvement learning from television advertising.41A particularly useful dif-ferentiation was suggested by Houston and Rothschild, who distinguished be-tween situational involvement, that is, the short-term need to make a judgment,

and enduring involvement, that is, motivation related to the long-term or inherent qualities of an object or topic linked to an individual’s personality.42

In social psychology, the Elaboration Likelihood Model (ELM)43 and the lesser-known Heuristic-Systematic Model (HSM)44both posit that topic-relevant involvement can play a pivotal role in the strategies people use to process informa-tion. High involvement individuals process information effortfully (ELM) or sys-tematically (HSM), whereas individuals with low involvement rely on cognitive shortcuts referred to as peripheral cues (ELM) or heuristics (HSM). Both models posit that behavior change effected by central route (ELM) or systematic (HSM) processing is more effective and enduring than persuasion that relies on peripheral route (ELM) or heuristic (HSM) processing.

J. Grunig recognizes the importance of involvement in the development of issues in public relations. He drew on Krugman to define involvement as the degree to which a person feels “connected” to an issue.45 In situational theory, high involvement (combined with high problem recognition and low constraint recognition) leads to greater information gain. Theus has similarly pointed to the importance of involvement as a central factor in information processing, suggest-ing that “problem recognition,” as stated in Grunig’s situational theory, might be reconsidered as a component measure of involvement.46

Elsewhere, Heath and Douglas documented the importance of involvement in discussions in public policy issues. Involved individuals exert more effort to communicate, as evidenced in being able to generate more cognitive responses (pro or con), engage in greater reading and television viewing, and discuss issues more with others when compared to uninvolved individuals.47 Cameron sug-gested that involvement can be explained functionally as a process of spreading activation within associated networks in memory.48

ALTERNATE STRATEGIES FOR COMMUNICATING WITH PUBLICS

Communicating with inactive publics, characterized by low levels of knowledge and involvement, impose special challenges to public relations communicators—problems that have been overlooked in theorizing about dealing with publics.

Normative theorists contend that the ideal way to practice public relations involves two-way, symmetric communication.49 Such approaches make sense when an organization is responding to active publics, where the principal actors involved in communication exchanges are the leaders of a social movement or special interest group. Generally, these leaders are both highly motivated and able to engage in an active, two-way collaboration. J. Grunig has argued that symmetric communication involves (“can include”) central route processing.50Indeed, the idea of two-way, symmetric communication is important to the extent that it is an ideal or a strategy to be used by organizations to be open to the worldviews of others and contributes to a more accurate enactment of the environment around

them.51However, two-way, symmetric communication might not be adequate to describe what actually occurs in organizational–public relationships, except in limited instances.

Coleman has observed that modern society is becoming increasingly asym-metric in its orientation, particularly with the rise of corporate entities. He suggests that at least three types of relational exchanges can take place: person-to-person, corporate-to-corporate and corporate-to-person.52Notions of two-way, symmet-ric communication make sense in communication exchanges involving one orga-nization to another orgaorga-nization, such as large corporation dealing with a large activist group, such as an environmental group, a labor union, or competing corporation. However, when the exchange crosses levels of actors and involves a corporate-to-person exchange, the presumption of symmetric communication is problematic. Significantly, this is not because of the organization’s lack of com-mitment to fostering good relationships. Instead, the lack of balance stems from the lesser motivation and ability found on the part of the public in any exchange with an organization.

Despite efforts to personalize organizations, that is, to help organizations develop a persona,53theorists confound reality when they suggest that communi-cations involving a large unnatural organization operates in the same way as communication among natural persons. Coleman observes that corporate actors (1) typically have large resources, (2) nearly always control the conditions sur-rounding the relationship, and (3) control much of the information relevant to the interaction.54This is not unexpected because often, organizations possess far more knowledge and are more involved. Indeed, organizations often have greater in-centives to establish and maintain a relationship and extract favorable outcomes with potential customers, investors, donors, employees, or voters than do the publics with whom they are trying to establish and maintain a relationship.

The issue of probable asymmetry is particularly important when dealing with inactive publics, where large organizations inherently possess greater power.55The concern here does not involve attempts to exploit or manipulate people. Rather, with the possible exception of its highest leadership, the rank-and-file members of many publics are never likely to share the same level of knowledge and involvement about a topic as the organization that seeks to communicate with them about it. Many times, individual members of publics have other options available to them and thus might have less incentive to increase either their knowledge or involve-ment.

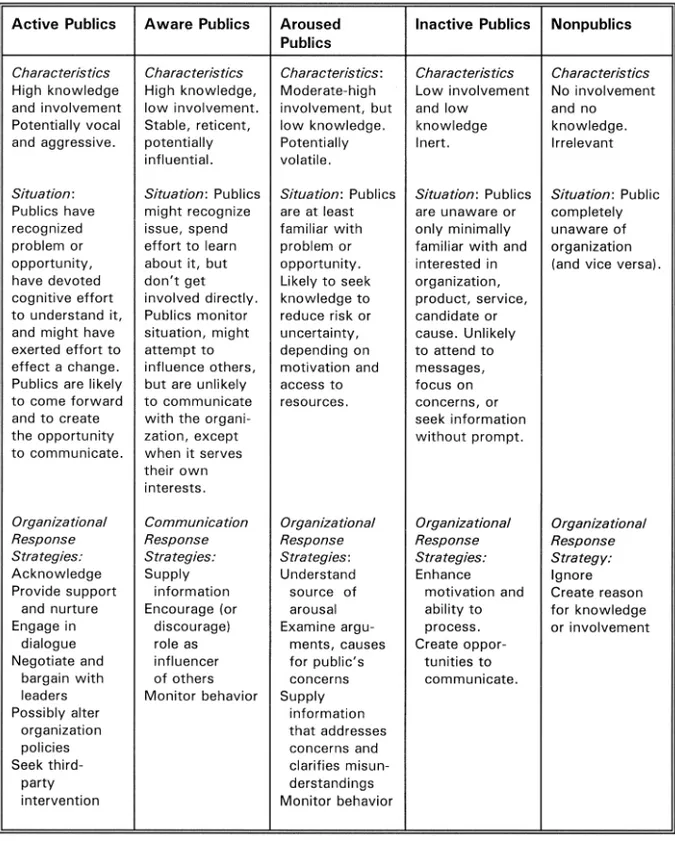

Figure 2 illustrates the alternatives challenges confronting an organization when dealing with publics that might be found in each category. Figure 2 also suggests that the communication strategies appropriate to pursue are considerably different depending on the type of public involved.

Active publics, that is, those with high knowledge and involvement, are the groups most likely to be organized, with formal structures and leaders, and are most likely to collaborate. Organizations do not need to attract attention or entice active publics to communicate with them. The public will come to them and will create their own opportunities to communicate.

On the other hand, merely aware publics and merely aroused publics are much less likely to be organized or to be spearheaded by a leadership group that presses demands. Organizations dealing with aware or merely aroused publics are likely to need to respond to individual members of these groups on an individual

Figure 2. Alternative Strategies for Communicating with Publics Public Relations Review

basis. Members of aware or aroused publics might call, write, or visit as part of their process of monitoring (aware publics) or active information- or remedy-seeking (aroused publics). The imperative of the organization is to be responsive to such inquiries and thus seize opportunities to build relationships or to contain potential problems that might escalate later. Organizations also might choose to seek out such groups and to educate them or allay their concerns, as appropriate.

By contrast, inactive publics (and certainly nonpublics) are unlikely to en-gage in any deliberate information seeking efforts, other than to satisfy routine personal needs. In the case of inactive publics, it becomes incumbent on organi-zations to seek out these groups, not because they are will become activists, but rather to build positive relationships. Organizations must initiate and assume responsibility for the communication process because of the unrecognized or marginal interest often exhibited by inactive publics.56

The inertia that characterizes inactive publics places the burden on the organization to establish communication programs that gain the attention and engage less attentive publics. Indeed, this often merits use of techniques associated with the much-maligned models of public relations involving press agentry; public information; and one-way, asymmetrical communication. Indeed, before any higher-order levels of communication (such as dialogue or negotiation) can begin, it is first necessary to engage otherwise inattentive publics. This involves enhancing their motivation and ability to focus on the organization and its messages and by providing adequate opportunities for them to do so.57

CONCLUSION

This article challenges contemporary thinking about public relations by reminding theorists and researchers about inactive publics, a category of publics that have been largely ignored in the literature. Inactive publics need to be understood better because of the large numbers of people they often represent and the emphasis placed on them in many public relations campaigns as organiza-tions strive to influence the way inactive publics buy, invest, donate, work, and vote. Inactive publics, as a group, are important, long-term constituents for many organizations, which are desperately seeking ways to do a better job of communi-cating with them.

By defining inactive publics as groups with low involvement and low knowl-edge in an organization (or its products, services, candidates, or causes), this article has identified two of the most critical variables that also merit greater theoretical attention from the field. The degree to which an individual or group is involved or perceives that an organization is relevant to them personally is a critical factor in determining the degree to which people are motivated to attend to or respond to an organization’s public relations efforts. At the same time, the degree to which an individual or group is knowledgeable about an organization dramatically influ-ences their ability to comprehend those efforts and to respond accordingly.

From this discussion it should be evident that a wide range of alternative

response strategies, based on whether a public is active, merely aware, merely aroused, or inactive, might be appropriate. Although normative theory suggests that public relations is ideally practiced as two-way, symmetric communication, that notion has been challenged in recent years by contingency theories that suggest that a combination of advocacy and accommodation might be called for.58 The model presented here contributes to that discussion by suggesting that advo-cacy might be especially valuable, to the extent that a particular public is less active, that is, less involved and less knowledgeable, in a particular topic or issue. More-over, the alternative strategies suggested in Figure 2 go beyond the simple advocacy–accommodation continuum suggested by others to outline some of the more specific response strategies that an organization might undertake.

Notes

1. James E. Grunig and Larissa A. Grunig, “Models of Public Relations,” in James E. Grunig (ed.), Excellence in Public Relations and Communication Management (Hill-sdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 1992), pp. 285–325; Larissa A. Grunig, “Activism: How it Limits the Effectiveness of Organizations and How Excellent Public Relations Departments Respond,” in James E. Grunig (ed.), Excellence in Public Relations and Communication Management, op. cit., pp. 503–530; James E. Grunig and Todd Hunt, Managing Public Relations (New York, NY: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1984).

2. James E. Grunig, “A Situational Theory of Publics: Conceptual History, Recent Challenges and New Research,” in Danny Moss, Toby MacManus, and Dejan Vercic (eds.), Public Relations Research: An International Perspective (London: Interna-tional Thomson Publishing, 1997), pp. 3– 48, 282–288.

3. Glen M. Broom, Shawna Casey, and James Ritchey, “Toward a Concept and Theory of Organization-Public Relationships,” Journal of Public Relations Research 9 (1997), pp. 83–98; James E. Grunig and Yi-Hui Huang, “From Organizational Effectiveness to Relationship Indicators: Antecedents of Relationships, Public Rela-tions Strategies and RelaRela-tionship Outcomes,” in John A. Ledingham and Stephen D. Bruning (eds.), Relationship Management: A Relationship Approach to Public Rela-tions (Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 2000), pp. 23–54.

4. Sylvia H. Goldman and Kathryn T. Theus, “The Relationship Between Organiza-tional Communication Style and the Motivation of Publics to Seek Information to Meet Their Needs,” paper presented to Public Relations Interest Group, Interna-tional Communication Association, July 1994, Sydney, Australia.

5. John Dewey, The Public and Its Problems (Athens, Ohio: Swallow Press, 1927); Herbert Blumer, “The Mass, The Public and Public Opinion,” in Bernard Berelson (ed.), Reader in Public Opinion and Communication, 2nd ed. (New York: Free Press, 1966), pp. 45–50. (Originally published in 1946.)

6. James E. Grunig and Fred C. Repper, “Strategic Management, Publics and Issues,” in James E. Grunig (ed.), Excellence in Public Relations and Communication Manage-ment (Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 1992), p. 124.

7. Ibid, p. 125.

8. R.E. Freeman, Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach (Boston: Pitman, 1984).

9. Carroll J. Glynn, “Public Opinion as a Normative Opinion Process,” Communication Yearbook, Vol. 20 (Thousand Oaks, CA.: Sage Publications, 1997), pp. 157–183. 10. Herbert Blumer, op. cit., pp. 186 –187.

11. A.P. Cohen, The Symbolic Construction of Community (New York: Tavistock, 1985). 12. Emile Durkheim, The Division of Labor in Society, (trans. by G. Simpson) (New York: Macmillan, 1947) (Original work published 1893); Ferdinand Tonnies, Community and Society. Gemeinschaft and Gessellschaft (East Lansing, MI: Michigan State Uni-versity Press, 1947).

13. Walter Lippmann, Public Opinion (New York: Harcourt Brace and Co., 1922). 14. Walter Lippmann, The Phantom Public (New York: Harcourt Brace and Co., 1925). 15. John Dewey, op. cit.; Herbert Blumer, op. cit.; C. Wright Mills, The Power Elite (Oxford, England: Oxford University Press, 1956); Ju¨rgen Habermas, The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere: An Inquiry Into A Category of Bourgeois Society, (trans. by Thomas Burger with Frederick Lawrence) (Cambridge, MA.: MIT Press, 1989) (Originally published in 1962).

16. Antonio Gramsci, Selections from the Prison Notebooks, Q. Hoare and G. N. Smith (eds.), (New York: International Publishers, 1971); Karl Marx and Frederich Engels, The German Ideology, (trans. by J. Arthur), (New York: International Publishers, 1947).

17. R. A. Bauer, “The Obstinate Audience: The Influence Process from the Point of View of Social Communications,” American Psychologist 19 (1964), pp. 319 –328; Brenda Dervin, “Audience as Listener and Learner, Teacher and Confidant: The Sense-Making Approach,” in Richard Rice and Charles Atkins (eds.), Public Communica-tion Campaigns, 2nd ed. (Newbury Park, CA: Sage PublicaCommunica-tions, 1989), pp. 67– 86. 18. Susan T. Fiske and Shelley E. Taylor, Social Cognition, 2nd ed. (New York: Random

House, 1992).

19. Richard Wurman, Information Anxiety (New York: Doubleday, 1989).

20. Stephen Hilgartner and Charles L. Bosk, “The Rise and Fall of Social Problems: A Public Arenas Model,” American Journal of Sociology 94 (1988), pp. 53–78. 21. Amanda E. Cancel, Michael A. Mitrook, and Glen T. Cameron, “Testing the

Con-tingency Theory of Accommodation in Public Relations,” Public Relations Review 25 (1999), pp. 171–198.

22. Jeffrey Pheffer and Gerald Salancik, The External Control of Organizations (New York: Harper and Row, 1978).

23. Robert L. Heath, Strategic Issues Management, (Thousand Oaks, CA.: Sage Publica-tions, 1997); Anders Gronstadt, “Integrated Communications at America’s Leading Total Quality Management Corporations,” Public Relations Review 22 (1996), pp. 25– 42.

24. John W. Thibaut and Harold H. Kelley, The Social Psychology of Groups (New York: John Wiley and Sons, 1959).

25. James E. Grunig and Todd Hunt, op. cit., p. 154.

26. James E. Grunig and Todd Hunt, op. cit.; Roger W. Cobb and Charles D. Elder, Participation in American Politics: The Dynamics of Agenda-Building (Boston, MA.: Allyn and Bacon, 1972), pp. 104 –109.

27. Elihu Katz and Paul A. Lazarsfeld, Personal Influence (Glencoe, IL.: The Free Press, 1955).

28. James E. Grunig and Todd Hunt, op. cit., p. 145.

29. Sylvia H. Goldman and Kathryn T. Theus, op. cit.; Kathryn T. Theus, “Toward Respecifying Motivation and Decision Models: Analogues Between Grunig’s

Situation-Based Theory of Communication Behavior and Lawlor’s Expectancy The-ory,” paper presented to Public Relations Interest Group, International Communi-cation Association, May 1993, Chicago.

30. Stephen J. Hoch and Young-Won Ha, “Consumer Learning: Advertising and the Ambiguity of Product Experience,” Journal of Consumer Research 13 (1986), pp. 221–233.

31. Martin Fishbein and Icek Azjen, Belief, Attitude, Intention and Behavior: An Intro-duction to Theory and Research (Reading, MA.: Addison-Wesley, 1975).

32. Glen T. Cameron, “Spreading Activation and Involvement: An Experimental Text of the Cognitive Model of Involvement,” Journalism Quarterly 70 (1993), pp. 854 – 867.

33. Joseph W. Alba and L. Hasher, “Is Memory Schematic?” Psychological Bulletin 93 (1983), pp. 203–231; Susan T. Fiske and Shelley E. Taylor, op. cit.; Larissa A. Schneider (aka Grunig), “Implications of the Concept of Schema for Public Rela-tions,” Public Relations Research and Education 2 (1985), pp. 36 – 47.

34. Joseph W. Alba, “The Effects of Product Knowledge on the Comprehension, Reten-tion and EvaluaReten-tion of Product InformaReten-tion, ” in Richard M. Bagozzi and Alice M. Tybout (eds.), Advances in Consumer Research 10 (Provo, UT: Association for Con-sumer Research, 1985), pp. 377–380.

35. Michelene T. H. Chi, Robert Glaser, and M. J. Fair, (eds.), The Nature of Expertise (Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 1988); C. W. Sherif, M. Sherif, and R. E. Nebergall, Attitude and Attitude Change: The Social Judgment-Involvement Approach (Philadelphia, PA.: Saunders, 1965).

36. Lien-Ti Bei and Richard Heslin, “The Consumer Reports Mindset: Who Seeks Value—The Involved or the Knowledgeable?” in Merrie Brucks and Deborah J. MacInnis (eds.), Advances in Consumer Research 24 (Provo, UT: Association for Consumer Research, 1997), p. 24; Mita Sujan, “Consumer Knowledge: Effects of Evaluation Strategies Mediating Consumer Judgments,” Journal of Consumer Re-search 12 (1985), pp. 31– 46.

37. Richard A. Petty and John T. Cacioppo, Communication and Persuasion: Central and Peripheral Routes to Persuasion (New York: Springer-Verlag, 1986).

38. Andrew A. Mitchell, “Involvement: A Potentially Important Mediator of Consumer Behavior,” in William L. Wilkie (ed.), Advances in Consumer Research 6 (Ann Arbor, MI: Association for Consumer Research, 1979), p. 194

39. Glen T, Cameron, op. cit.; Charles T. Salmon, “Perspectives on Involvement in Communication Research,” in Brenda Dervin and Melvin Voight (eds.), Progress in Communication Sciences 7 (Norwood, NJ: Ablex, 1986), pp. 243–268.

40. Muzafer Sherif and Hadley Cantril, The Psychology of Ego Involvement (New York: John Wiley and Sons, 1947).

41. Herbert E. Krugman, “The Impact of Advertising Involvement: Learning Without Involvement,” Public Opinion Quarterly 29 (1965), pp. 349 –356.

42. Michael J. Houston and Michael L. Rothschild, “Conceptual and Methodological Perspectives on Involvement,” in S. Jain (ed.), Research Frontiers in Marketing: Dialogues and Directions (Chicago: American Marketing Associations Educators Conference Proceedings, 1978), pp. 184 –187.

43. Richard E. Petty and John T. Cacioppo, op. cit.

44. Shelley Chaiken, “Heuristic Versus Systematic Information Processing and the Use of Source Versus Message Cues in Persuasion,” Journal of Personality and Social Psychol-ogy 39 (1980), pp. 752–766.

45. James E, Grunig, 1997, op. cit.; James E. Grunig and Fred Repper, op. cit., p. 136 46. Kahtryn Theuss, op. cit.

47. Robert L. Heath and William Douglas, “Involvement: A Key Variable in People’s Reactions to Public Policy Issues,” in James E. Grunig and Larissa A. Grunig (eds.), Public Relations Research Annual 2 (Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 1990), pp. 193–204.

48. Glen T, Cameron, op. cit.

49. James E. Grunig, op. cit.; James E. Grunig and Todd Hunt, op. cit., 1989. 50. James E. Grunig and Larissa A, Grunig, op. cit., pp. 310 –311.

51. Karl E. Weick, The Social Psychology of Organizing, 2nd ed. (Reading, MA.: Addison-Wesley, 1979).

52. James S. Coleman, The Asymmetric Society (Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press, 1982).

53. Robert L. Heath, Management of Corporate Communication (Hillsdale, NJ: Law-rence Erlbaum Associates, 1994).

54. James E, Coleman, op. cit., pp. 21–22.

55. Michael Karlberg, “Remembering the Public in Public Relations Research: From Theoretical to Operational Symmetry,” Journal of Public Relations Research 8 (1996), pp. 263–279.

56. Sylvia H. Goldman and Kathryn T. Theus, op. cit.

57. Kirk Hallahan, “Enhancing Motivation, Ability and Opportunity to Process Public Relations Messages,” Public Relations Review 26 (Winter 2000), pp. 463– 480. 58. David M. Dozier, James E. Grunig, and Larissa A. Grunig, Managers Guide to

Excellence in Public Relations and Communication (Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 1995), p. 48; Amanda E. Cancel, Michael A. Mitrook, and Glen T. Cameron, op. cit.

상황이론의 블로거 공중 세분화 적용 연구*

1) 박노일** 연세대학교 커뮤니케이션연구소 전문연구원 블로고스피어의 급속한 확산과 사회정치적 영향력 확대는 저널리즘은 물론 PR활동의 중요한 연구 대상으로 부각하였다. 특히, 블로거들이 조직체의 명성 과 이익에 중대한 영향을 미칠 수 있다는 배경에서 활동적인 블로거 공중을 세 분화할 PR연구의 필요성이 제기된다. 이 연구는 공중 세분화 연구에서 그 가치 와 유용성을 국내외적으로 인정받아 온 그루닉의 상황이론을 그대로 블로고스 피어에 적용하여 이론의 유용성을 점검하는 데 목적을 두고 있다. 구체적으로, 상황이론을 ‘쌀 소득보전 직접지불사업(쌀 직불금)’과 ‘식품안전(멜라민파동)’ 쟁점을 중심으로 블로거 공중을 세분화하고자 했다. 온라인 설문조사로 수집된 블로거 895명의 답변 자료를 구조방정식 모델(SEM)을 통해 분석한 결과, 두 가지 연구 쟁점 모두에서 블로거들의 쟁점에 대한 지각과 커뮤니케이션 활동을 모델로 반영한 상황이론의 구조방정식 모델이 낮은 적합도를 갖는 것으로 나타 났다. 이는 전통적인 공중세분화 모델인 상황이론이 블로고스피어의 현실 상황 을 하나의 구조적 모델로 반영하는 데 한계가 있음을 실증적으로 제시한다. 이 러한 연구 결과는 상황이론을 블로고스피어에 적용하기 위해서는 상황이론의 수정, 또는 새로운 공중세분화 모델연구를 촉발한다. 주제어:블로그, 블로거, 공중, 상황이론, 공중 세분화 * 이 연구는 저자의 박사학위 논문(2009) 중 일부자료를 활용하였으며, 2009년 정부(교육과학기 술부)의 재원으로 한국연구재단의 지원을 받아 수행된 연구임[NRF-2009-352-B00051]을 밝힙 니다. ** zzualra@yonsei.ac.kr1. 서론

블로그(blogs)의 부상은 저널리즘 분야뿐만 아니라 산업과 마케팅 분야에 서도 급격한 변동과 영향력을 행사하고 있다(Lim & Yang, 2006). 특히, 많은 혁신적인 미디어 환경 변화 중에서 블로그의 등장만큼 PR(Public Relations) 영역에 영향을 미치는 뉴미디어는 없을 것이다(Messner, 2005). PR관점에서 블로거들(bloggers)1)이 뉴스 가치를 창출하고 조직체와 관련된 정보의 해석 과 확산에 영향을 미칠 수 있다는 것, 그리고 전통적인 저널리스트와 달리 활동적 블로거들이 저널리즘적인 역할을 보완하거나 대신한다는 배경에서 블로거 공중의 중요성이 부각된다. 이러한 블로거 공중의 영향을 반영하듯 이미 일부 PR연구자는 물론 실무자들도 블로거들에게 관심을 갖기 시작하였 다. 실제로 다수의 연구자들이 블로거들을 제품, 서비스 혹은 회사나 조직체 의 명성과 이익에 치명적인 영향을 미칠 수 있는 존재로서 조직체가 직접 접촉해야 하는 핵심 공중이라고 지적하고 있다(Edelman & Intelliseek, 2005; Flynn, 2006; Messner, 2005; Porter, Sweetser, Chung, & Kim, 2007; Sweetser & Metzgar, 2007; Trammell 2006; Wilson 2007; Wilcox, Cameron, Ault, & Agee 2007; Wright & Hinson, 2006).

하지만 PR측면에서 모든 블로거들이 관심을 가져야 할 목표 공중으로 간주되진 않는다. 활동적이며 사회적으로 영향력을 행사하는 블로거, 소위 파워 블로거(power blogger)들이 주 관심 대상이다. 그런데 이들의 힘은 그들의 독특한 블로깅 패턴으로 기인된다는 점을 주목할 필요가 있다. 9·11 사태 이후 사회적으로 주목을 받은 블로거들의 활동 사례들을 살펴보면, 전통적인 저널리스트의 활동방식과는 상이한 방법으로 정치, 경제, 사회 전 반에 영향력을 행사하고 있기 때문이다. 이러한 이유로 PR실무자들은 조직 체에 대한 긍정적인 정보를 확산시켜 주거나 영향력을 행사할 수 있는 대상 으로서 블로거들을 모니터하는 한편, PR연구자들은 활동적인 블로거 공중을 1) 블로거(blogger)는 블로그 운영자를 말한다.

식별해 내는 모델이나 이론을 발전시키고자 노력하고 있다(Park, Jeong, & Han, 2008).

공중을 세분화한 연구는 그루닉의 상황이론(situational theory)을 중심으 로 살펴볼 수 있다(Grunig, 1978; 1979a; 1979b; 1983; Grunig & Childers, 1988; Grunig & Hunt, 1984; Grunig & Repper, 1992). 1968년 메릴랜드 (Maryland) 대학의 그루닉과 그의 동료들이 주창한 상황이론은 이후 많은 연구자들이 꾸준히 검증해 왔다. 상황이론에 따르면 공중이란 지속적으로 변화하는 상황적인 집단으로 이슈나 상황에 따라 발생하였다가 그 문제가 해결되면 소멸하는 특성을 가진다. 이런 배경에서 일반 공중이란 개념은 PR의 관점에서는 의미가 없다(Grunig & Hunt, 1984). 공중이란 쟁점을 중심 으로 형성되기 때문에 일반적인 공중이란 존재할 수 없기 때문이다. 다시 말해, 공중이란 쟁점이 사라지면 소멸되는 기능적인 집단화(functional groupings)로 정의될 수 있다(Grunig & Repper, 1992). 이것은 공중이 인구 사회학적 변인을 중심으로 연령, 교육, 수입, 인종, 종교, 지리, 정치, 직업 등으로 구분되기보다는 쟁점을 중심으로 형성됨을 의미한다. 하지만, 인터넷과 블로고스피어2)의 확산으로 인해 상황이론은 ‘선택과 참여’라는 행위를 통해 자신을 드러내는 온라인 공중들을 구분하고(배미경 2003, 216쪽) 1인 미디어로 활동하는 공중을 유효적절하게 식별하는 데 한계 를 가질 것으로 예측된다. 수동적으로 대중매체의 정보를 수용하기만 하던 공중이 아니라 공중 개개인이 정보의 생산과 유포, 소비를 동시에 수행하는 하나의 미디어적 속성을 갖기 때문이다. 다시 말해, 블로거들은 상황이론이 전제하는 커뮤니케이션의 마지막 수용자가 아니라 왕성한 커뮤니케이션 생 산자이자 행위지로서 특정 주제나 영역에만 한정하지 않고 잠재적으로 전 지구적 영향력과 파급효과를 가질 수 있기 때문이다(Dillon, 2004; Edelman & Intelliseek, 2005; Flynn, 2006; Hall, 2006; Porter, et al., 2007; Sweetser

2) 블로고스피어(Blogosphere)는 커뮤니티나 사회적 네트워크로서의 모든 블로그를 일컫는 합성어로, 블로그 세계(world of blogs)를 뜻한다.

& Metzgar, 2007; Trammell, 2006; Wilson, 2007). 이러한 블로고스피어의 급속한 팽창과 블로거들의 사회적 영향력 증가는 PR관점에서 상황이론을 그대로 블로고스피어에 적용 가능한지를 점검해 보 는 작업을 요청한다. 따라서 이 연구는 시의성의 높은 사회정치적 쟁점을 선정하여 상황이론의 기본 모델이 블로고스피어에 적용 가능한지를 구조방 정식 모델을 통해 검증하고자 한다. 상황이론이 쟁점을 중심으로 뭉쳐진 블로거들을 적절히 세분화하는 유용한 모델이 될 수 있는지를 실증적으로 검증하는 데 구조방정식 모델을 이용하여 살핀다는 것이다. 이러한 이유는, 지금까지 상황이론의 검증연구가 각 쟁점에 대해서 개별 변인의 인과적 유의 성이나 상황이론에 따른 집단별 차이를 중심으로 살피고 있지만, 또 이러한 결과가 비록 상황이론 변인들 간의 인과관계 혹은 집단 간 차이를 설명해 줄 수 있겠지만, 상황이론이 하나의 모델로서 현상을 어느 정도 간명하게 설명하는지를 실증적으로 제시하지 못한다고 보았기 때문이다. 이런 배경에 서 이 연구는 구조방정식 모델 검증을 통해 상황이론의 블로고스피어 적용 가능성을 보다 엄밀하게 검증해 보고자 한다. 이러한 시도는 상황이론의 유용성이나 한계를 실증적으로 면밀히 확인하고 차후 블로거 공중 세분화 모델연구를 촉발하는 계기가 될 것이다. 2. 이론적 논의 1) 블로그와 블로고스피어의 확산 1997년 미국에서 등장한 블로그는 2001년 9·11 사태를 계기로 널리 알려 지게 되었는데(Adamic & Glance, 2005; Gillmore, 2004; 2005), 전통적인 미디어에 비해 제작과 정보 이용의 접근성, 편리성, 유용성, 그리고 이용자의 상호작용성 등으로 인해 전 세계적으로 그 수가 증가하고 있다(Drezner & Farell, 2004; Kaye, 2005; 2007). 특히, 초기의 블로그는 게시글이나 포스트

에 대한 링크를 중심으로 이뤄졌으나 기술적으로 트랙백(track back)과 RSS(Really Simple Syndication)과 같은 상호작용 기능이 추가되어 그 이용이 더욱 증가하였다. 또한 대부분의 블로그 설치와 운영이 무료로 이용될 수 있다는 점으로 인해 이용자가 증가하고 있다. 실제, 블로그를 만드는 시간은 서비스 포털의 프로그램을 지원받아 설치하면 채 10분이 걸리지 않는다 (Drezner & Farrell, 2004).

블로그의 수가 확산되는 또 다른 이유는 블로그의 공개적인 속성에 기인한 다고 볼 수 있다. 블로그의 게시 내용은 블로거의 아침 식사 메뉴가 무엇이었 는지부터 시작해서 전 세계적인 이슈에 관한 것까지 다양하다(박노일·남은 하, 2008). 지극히 개인적인 일상사나 이야기, 혹은 날카로운 사회비판까지 다양한 쟁점들에 대한 담론들이 블로그 포털사이트 등을 통해서 쉽게 전파되 고 공유되는 속성을 가진다. 바로 옆집 이웃 혹은 자신과 유사한 사람들의 생각이나 의견이 블로그를 통해 전파되면서 블로그 이용자들은 기성 미디어 보다 블로그를 더 신뢰하며 더 높은 의존도를 보이기도 한다(박노일, 2008). 이렇게 일반 시민들이 이야기나 목소리가 사회적으로 공개하고 공유하는 속성은 블로고스피어 확산에 일조하였다(Blood, 2002). 한편, 개별적인 블로그의 특성에 비해 블로그 네트워크인 블로고스피어는 독특한 구조적 특성을 갖고 있다. 한마디로 블로고스피어는 불평등한 네트워 크 구조를 기반으로 한다. 블로거들이 상호 긴밀하게 연결되어 있을 것 같지 만 실제로는 많은 블로거들이 상호 연동되어 있지 않다. 반면 특정 소수 영향력 있는 블로거들은 조밀한 연결망을 확보하고 있다. 비록 블로그가 ‘사람들을 위한 목소리(voice for people)’나 누구나 발언할 수 있는 길거리의 ‘가두연설(soapbox)’ 공간으로 상징되지만(Herring, Scheidt, Bonus, & Wright, 2004; Sweetser & Kaid, 2008; Walker, 2005; Winer, 2003), 모든 블로그가 시민의 목소리를 대변하거나 가두연설 무대를 제공하지는 못한다는 것이다 (박노일·한정호, 2008).

결국, 블로고스피어에서 다양한 의견과 교류가 가능할 수 있지만 그 세계가 더 커지고 복잡해질수록 블로고스피어는 더 불균형하며 멱함수

법칙(power law)3)에 따라 특정 블로거에게 파워가 심하게 쏠리게 된다

(Barabasi, 2002; Bar-Ilan, 2005; Drezner & Farrell, 2004; Shirky, 2003). 이러한 배경에서 블로고스피어에서 비균형적으로 많은 방문을 받는 블로거 들이 파워를 행사한다. 예를 들어, 특정 미디어적 기능을 하는 유명 블로거가 대부분의 일반 블로거들로부터 주목을 받고 영향력을 행사하는 것이다 (Drezner & Farrell, 2004). 영향력 있는 블로거 혹은 파워 블로거의 출현은 블로고스피어에 존재하는 블로거들이 기본적인 선택의 자유를 갖고 있기 때문에 나타나는 필연적인 현상이다. 실제로 미국의 블로그 433개 중 3%인 상위 12개의 블로그가 20% 이상의 링크를 받는다는 연구 결과는 이러한 논의를 뒷받침해 준다(Shirky, 2003). 그러나 비록 멱함수 법칙이 네트워크를 선점한 승자가 독식한다는 논리를 제공하긴 하지만 이는 인터넷 공간의 구조적인 불평등에도 불구하고 특정 쟁점을 중심으로 후발 주자가 승자의 자리를 뒤엎거나 빈약한 소수의 노드가 갑자기 집중적인 링크를 받는 현상에 대해서는 설명을 못하고 있다(박노일· 한정호, 2008; Barabasi, 2002). 구조만으로 블로고스피어의 파워 구조나 변동을 모두 설명할 수 없다는 것이다. 다시 말해, 비록 링크를 많이 받는 블로그가 지속적으로 성장할 수는 있겠지만 시간을 축으로 살펴보면 블로그 구조보다 블로거들의 커뮤니케이션 행위나 활동으로 인해서 블로고스피어 의 파워는 변동될 수 있다는 것이다(박노일·한정호, 2008; Drezner & Farrell, 2004). 따라서 블로고스피어에서 활동하는 블로거 공중을 연구하기 위해서는 단 순히 방문자가 많은 몇몇 순위 블로그 리스트를 주목하기보다는 쟁점을 중심 으로 뭉쳐 활동하는 블로거들의 독특한 행위를 주목할 필요가 있다. 쉽게 포털에서 구할 수 있는 정보를 긁어다가 놓은 블로그가 블로고스피어에서 많은 방문자를 확보하고 상위 리스트에 위치할 수 있기 때문이다(김익현, 3) 멱함수 법칙(power law)에 따른 분포는 평균 주위에 정점(頂點)이 없고 크기가 커짐에 따라 계속 감소하는 모양을 갖는다. 멱함수 분포를 따르는 네트워크에서는 연결선이 적은 점들이 대부분이지만 동시에 연결선이 많은 점들도 적지만 함께 존재한다는 것이다.

2005). 다시 말해, 상위 리스트의 블로그는 블로고스피어에서 특정 쟁점에 대한 의제를 설정하고 확산시키며 버즈(buzz)4) 형성의 주도자라기보다는 대중의 구미에 맞는 레퍼토리가 다양한 레스토랑의 메뉴판과 같을 수 있기 때문이다. 2) 블로거 공중 인터넷 보편화 등 매체환경의 변화는 다양한 미디어 주체를 양산해 왔다. 이는 곧 온라인 공간에서 적극적으로 활동하는 공중의 부각을 의미하며, 이들은 또 언제든지 특정 조직체를 위협할 수 있는 잠재력을 가진다는 것을 의미한다(배미경, 2003; 한정호·박노일·정진호, 2007). 이러한 배경에서 인터넷과 같은 온라인 매체를 행동주의적 매체로 간주한다(Holtz, 1999). 특히 블로고스피어의 등장은 수천만 명의 개별적인 사람들이 순식간에 활동 적인 공중으로 돌변할 수 있는 기술적 환경을 마련해 주었다(Paine & Lark, 2005). PR연구에서 공중을 식별하는 기본적인 목적은 변화하지 않겠지만 공중을 식별하는 데 핵심적인 두 용어가 쟁점과 커뮤니케이션이기 때문에 공중이 활동하는 공간이 이동되거나 커뮤니케이션 패턴의 변화는 활동적 공중에 대한 측정과 세분화 방법에 대한 재고를 요청한다고 볼 수 있다. 이미 인터넷 이용자를 정의하는 데 있어서 일방적으로 미디어 정보를 수용 하는 수동적인 존재가 아니라 이용자 혹은 정보 공동생산자라는 점에 대해서 는 대부분의 연구자가 동의하고 있다. 반면 인터넷 공간에서 활동하는 집단 이나 공중에 대한 명확하고 통일된 정의는 없다. 물론, 최윤희(2001)가 전자 환경과 새로운 공중을 논하면서 ‘전자공중’이라는 개념을 제기한 바 있지만 이는 단순히 인터넷 수용자 혹은 사이버 서퍼(cyber surfer) 등으로 지칭되어 왔다. 4) 버즈(buzz)는 블로고스피어에서 수많은 블로거들이 동일한 주제에 대해서 동시에 대화하거 나 토론하는 현상을 말한다.

최근 들어서야 온라인 공간에서 활동하는 공중을 ‘온라인 공중(online public)’으로 정의하기 시작했다(배미경, 2003; 한정호 외, 2007). 배미경 (2003)은 온라인 공중이란 인터넷을 서핑하다가 조직체 홈페이지 게시판, 토론방, 회원가입을 통해 자신의 정체성을 드러내는 지점에서 조직의 공중이 되기도 하고, 토론 등에 참여하면서 커뮤니케이션 행동을 보인다고 설명하고 있다. 이에 대해 한정호 등(2007)은 정체성을 드러내지 않는 공중의 활동도 간과되어선 안 된다고 지적하고, 인터넷 글쓰기뿐만 아니라 읽기도 중요한 커뮤니케이션 행위임을 지적하였다. 그들은 온라인 공중을 보다 광의의 개념 으로 온라인 공간에서 특정 쟁점이나 문제점을 중심으로 형성되는 집단이라 고 정의하였다. 선행 연구들은 온라인 공중들이 특정 쟁점을 지각하고 자신의 행동의 효과 를 예측하는 인식의 정도가 다르게 나타난다는 점을 강조하고 있다(Postmes & Brunsting, 2002). 반면, 블로거 공중은 인터넷 게시판, 토론방, 커뮤니티 이용자로 다소 느슨하게 정의되는 온라인 공중 개념과도 다를 것이라고 예측 된다. 블로거들은 대중 미디어를 소비하거나 인터넷을 이용하는 온라인 이용 자와는 다른 성격을 지닌다. 왜냐하면 블로거들은 미디어 수용자인 동시에 미디어 주체이기 때문이다. 무엇보다 블로거들은 커뮤니티나 게시판의 암묵 적 규범과 규칙에 영향 받지 않는다. 이들은 보다 더 자기중심적이고 주체적 이며 개인적이다. 블로그에 글을 쓴다는 것은 마치 자신만의 일기를 쓰는 형태와 같다고 간주한다. 자기 자신만의 미디어인 블로그를 소유하고 있기 때문에 자신의 블로깅 행위에 대한 제약인식이 약하다. 특히, 블로거 공중은 특정 쟁점에 대한 정보 수용자이면서 생산자의 위치 를 점하고 있는 상호작용적 존재이다(박노일, 2008). 이들은 그루닉의 상황 이론에서 가정하고 있는 대중 매체의 수용자가 아니다. 블로거 공중은 쟁점 이나 정보에 대한 공개와 참여를 기본으로 한다(Trammell & Keshelashvili, 2005). 블로거들은 관심 있는 분야에 대해 지극히 개인적인 의견이나 주장을 펼칠 수 있다. 하지만 블로거들의 커뮤니케이션은 고립되어 있다기보다는 생각을 같이 하는 동지(同志) 블로거들과 상호 연결되면서 뭉쳐져 하나의

떼(swarm)를 이루면서 쉽게 활성화되고 응고된 행동으로 구체화될 수 있다 (Scoble & Israel, 2006). 역설적이게도 블로거들은 지극히 개인적이지만 쉽 게 사회적으로 활성화된 공중으로 승화될 수 있는 속성을 가진다는 것이다. 블로거들이 관심 있는 쟁점에 대해서 정보를 추구하는 경향이 높을 뿐만 아니라 관련된 정보를 소화하는 경향도 높으며 이런 과정에서 정보의 생산과 수용이 교차적으로 이뤄져 공유와 합의, 그리고 집단적 행동으로 나타날 수 있기 때문이다. 결국, 블로거 공중은 서로 간의 정보의 생산과 교환, 수용, 비판, 상호긍정 그리고 지지와 참여가 높은 집단이라고 할 수 있다. 전체적으로 보면, 오프라인의 일반 공중이 쟁점을 중심으로 활동 공중으로 활성화되기 위해서는 커뮤니케이션 공간이 필요하듯이(Ni & Kim, 2009), 블로거 공중은 특정 쟁점에 대해 커뮤니케이션 할 수 있는 블로고스피어라는 사회적 공간이 필요하다. 이런 배경에서 블로거 공중은 오프라인 공중과 유사하게 쟁점을 중심으로 형성되는 집단이지만, 블로고스피어라는 특정 커뮤니케이션 공간에서 존재하는 블로거들의 무리나 집단이다. 특히, 활동적 인 블로거 공중은 특정 쟁점이나 문제점을 사회적으로 공개하고 여론화시키 는 데 있어서 막강한 네트워크 파워를 내재하고 있으며 그 영향력은 블로고 스피어뿐만 아니라 인터넷 공간과 오프라인 현실 공간에까지도 파급효과를 가진다. 지극히 개인적 블로깅의 자유로움을 가진 블로거 공중, 그러나 이들 이 블로고스피어의 네트워크의 파급력을 통해 온라인과 오프라인을 넘나들 며 공적인 힘을 발휘할 수 있는 특성을 가진다는 점에서 중요하다(Edelman & Intelliseek, 2005; Flynn, 2006; Porter, et al., 2007; Sweetser & Metzgar, 2007; Trammell, 2006; Wilson, 2007).

3) 상황이론

전술한 블로거 무리(swarm)의 적극적인 활동으로 블로고스피어뿐만 아니 라 사회 전반에 미치는 파급효과는 PR연구의 패러다임 변화를 요청하고 있다. 쟁점을 중심으로 뭉쳐진 블로거들은 블로고스피어의 네트워크를 통해

버즈를 만들어내고 형성되는 집단이므로 일종의 공중으로 간주될 수 있다. 이들은 공중 중에서도 블로고스피어에서 활동하는 공중이므로 이들을 어떠 한 방법으로 분류하고 세분화할 수 있는지가 관건이 된다. 전통적으로 PR연구는 상황이론을 동원하여 공중을 세분화해 왔다. 상황 이론에서는 쟁점에 대한 지각이 공중을 세분화하는 기초적인 근거를 제공하 고 있으며, 같은 집단의 공중은 상황에 대한 지각만 비슷한 것이 아니라, 그들의 커뮤니케이션 행동 또한 비슷하다고 가정하고 있다. 상황에 대한 지각이 공중을 형성하는 필수요소라고 말한다. 상황에 대한 문제인식 (problem recognition), 제약인식(constraint recognition), 그리고 관여도 (involvement) 지각에 따라 공중은 쟁점과 관련해 적극적 혹은 소극적으로 커뮤니케이션한다는 것이다. 예를 들면, 어떤 쟁점에 대해 자신이 뭔가 조치를 취해야 한다는 문제틀 (problematic)을 인식하는 수준이 높고, 이를 해결하는 과정에서 자신의 행 동을 계획하고 실행할 자유가 제한되는 수준이 낮다고 지각하며, 또 관련 쟁점에 대해서 자신과 연관성이 높다고 지각하는 고관여 상황이라면, 공중은 관련 정보를 적극적으로 추구하고 처리하는 커뮤니케이션 행동을 나타낸다 는 것이다. 이렇듯 상황이론의 기본 목적은 언제 어떻게 사람들이 커뮤니케 이션하고 어떤 커뮤니케이션이 가장 효과적일 수 있는지 찾아내는 데 있다. 실제로 그루닉(Grunig, 1983)은 환경문제에 대한 사람들의 태도나 인구사회 학적 배경으로 공중이 구분되기보다는 쟁점에 따라 공중이 활성화되고 분류 됨을 검증하였다. 지금까지 상황이론을 적용한 PR연구의 흐름은 그루닉의 상황이론에 대한 기본 검증(replication)과 확장(extension) 연구 형태로 진행되어 왔다. 공중 식별 연구는 상황이론을 중심으로 그 이론을 검증해 보거나 거기에 새로운 변인을 추가, 수정, 혹은 새로운 변인과 통합하며 변형시키는 형태로 이뤄진 것이다. 기본검증 연구는 다양한 상황에 상황이론을 적용하여 이론의 유용성 을 검증하는 연구이며(권중록, 2000; 김인숙, 1997; 남경태, 2006; 신호창· 홍주현, 2000; Atwood & Major, 1991; Grunig, 1978; 1979a; 1979b; 1983;

Hamilton, 1992; Major, 1993a; 1993b; 1998), 확장 연구는 상황이론의 기본 검증 연구뿐만 아니라 독립변인이나 종속변인을 추가하고 변형시키는 연구 로 분류된다(차동필, 2002a; 2002b; 2006; 윤희중·차희원, 1997; 1998; Aldoory, 2001; Lundy, 2005; Moghan, Daniel, & Sriramesh, 2005; Grunig & Childers, 1988; Sha & Lundy, 2005).

실제, 선행 연구들은 상황이론 변인들의 인과관계를 누적적으로 검증하였 을 뿐만 아니라, 상황이론에 따라 분류된 활동 공중이 다른 공중유형들보다 정보추구와 처리행동 수준이 높다는 것으로 상황이론을 검증하였다(권중록, 2000; 남경태, 2006; 김인숙, 1997; 한정호 외, 2007; 신호창·홍주현, 2000; 차동필, 2002a; 2002b; 2006; Atwood & Major, 1991; Grunig, 1978; 1979a; 1979b; 1983; Grunig & Childers, 1988; Hamilton, 1992; Hearit, 1999; Kim, Downie, & Stefano, 2005; Major, 1993a; 1993b; 1998; Phillips, 2001). 4) 상황이론의 블로거 공중 세분화 제한점 PR의 공중 세분화 연구는 전반적으로 그루닉의 상황이론을 중심으로 이뤄 져 왔다고 해도 과언은 아니지만 그루닉의 상황이론에 따른 공중 분류는 인터넷의 등장으로 새로운 변화가 요청된다. 기존의 공중 세분화 모델을 그대로 온라인에 적용할 수 있는가의 문제와 관련해서 몇몇 선행 연구들이 이의를 제기하고 있기 때문이다(배미경, 2003; 한정호 외, 2007; 한혜경, 2003; Hearit, 1999; Paine & Lark, 2005). 특히, 블로고스피어의 등장에 따른 블로거들의 블로깅은 오프라인 공간의 공중과 매우 상이한 커뮤니케이션 패턴을 가진다. 이러한 배경에서 기존의 그루닉의 상황이론을 그대로 블로고 스피어에 적용하여 블로거 공중을 세분화할 수 있는지에 대해 회의적 시각이 제기된다. 그렇다고 블로그를 운영한다는 사실 하나만으로 모든 블로거가 높은 수준 의 활동적 블로거라고 간주할 수는 없을 것이다(Powers, 2003; Rutigliano, 2007; Shirky, 2003 Trammell & Keshelashvili, 2005). 관심을 갖는 쟁점들이