저작자표시-비영리-변경금지 2.0 대한민국 이용자는 아래의 조건을 따르는 경우에 한하여 자유롭게 l 이 저작물을 복제, 배포, 전송, 전시, 공연 및 방송할 수 있습니다. 다음과 같은 조건을 따라야 합니다: l 귀하는, 이 저작물의 재이용이나 배포의 경우, 이 저작물에 적용된 이용허락조건 을 명확하게 나타내어야 합니다. l 저작권자로부터 별도의 허가를 받으면 이러한 조건들은 적용되지 않습니다. 저작권법에 따른 이용자의 권리는 위의 내용에 의하여 영향을 받지 않습니다. 이것은 이용허락규약(Legal Code)을 이해하기 쉽게 요약한 것입니다. Disclaimer 저작자표시. 귀하는 원저작자를 표시하여야 합니다. 비영리. 귀하는 이 저작물을 영리 목적으로 이용할 수 없습니다. 변경금지. 귀하는 이 저작물을 개작, 변형 또는 가공할 수 없습니다.

Impact of Pelvic Floor Dysfunction on Quality of Life

in Cancer Survivors and Development of

Pelvic Floor Muscle Rehabilitation Program

by

Eun Joo Yang

Major in Medicine

Department of Medical Sciences

The Graduate School, Ajou University

Impact of Pelvic Floor Dysfunction on Quality of Life

in Cancer Survivors and Development of

Pelvic Floor Muscle Rehabilitation Program

by

Eun Joo Yang

A Dissertation Submitted to The Graduate School of Ajou University

in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of

Ph. D. in Medicine

Supervised by

Ueon Woo Rah

, M.D., Ph.D.

Major in Medicine

Department of Medical Sciences

The Graduate School, Ajou University

Acknowledgements 처음부터 마지막까지 흔쾌히 기회를 주시고, 격려해주시고, 마칠 수 있도록 여러모로 가르쳐 주신 나은우 교수님께 진심으로 감사 드립니다. 암생존자를 위해 무언가를 해드리고 싶은 꿈만 있었던 제게, 연구를 시작할 수 있도록 장을 열어 주시고, 하나하나 가르쳐 주신 임재영 교수님께 감사 드립니다. 논문이 완성될 수 있도록 지도해 주시고, 중요한 일이라고 의미를 부여해 주셔서, 마칠 수 있는 힘을 북돋아 주신 전미선 지도 교수님, 양정인 교수님, 윤승현 교수님께 이 자리를 빌어 진심으로 감사 드립니다. 이 연구를 위하여 함께 환자분들을 면담하며 같은 마음으로 자료를 수집해 주신 김경희 연구원님께도 감사 드립니다. 무엇보다 지금도 몇 달에 한번씩 외래에 오셔서 반갑게 오히려 제 안부를 물어주시는 환자분들께 참으로 감사 드립니다. 수요일 마다 늦게 들어오는 저를 많이 이해해주고 좋아해주는 첫째 수민이, 돌 지난 지 이제 사흘 된. 젖 먹느라 새벽에 일어나 함께 컴퓨터 앞에 앉아 있었던 우리 둘째 성준이, 아이들을 더 많이 사랑해 주길 바라며 많이도 참아 주었던 고마운 남편, 가족이 있었기에 이렇게 마칠 수 있었습니다. 부족한 딸과 며느리를 조건 없이 사랑해 주신 부모님, 시어머님, 감사 드립니다. 무엇보다 예수님의 피로 하나님 자녀 삼아 주시고, 하나님 나라를 이루는 꿈을 새롭게 꾸게 하시는 하나님께서 지금도 함께 하심에 다시 시작합니다.

-ABSTRACT -

Impact of Pelvic Floor Dysfunction on Quality of Life in Cancer

Survivors and Development of

Pelvic Floor Muscle Rehabilitation Program

Purpose: This study was designed to evaluate the pelvic floor dysfunction and its impact

on quality of life in gynecological cancer survivors and to assess the effects of pelvic floor muscle rehabilitation program on pelvic floor dysfunction and quality of life in gynecological cancer survivors by a prospective randomized controlled trial.

Methods: Thirty-four subjects with gynecological cancer and 16 healthy women

completed a Korean version of pelvic floor questionnaire and Korean version of the EORTC QLQ-C30 and QLQ-CX24. Gynecological cancer survivors were randomly allocated to exercise group performing Pelvic Floor Rehabilitation Program (PFRP) or control group. All gynecological cancer survivors completed a Korean version of pelvic floor questionnaire and Korean version of the EORTC QLQ-C30 and QLQ-CX 24 and MEP by sacral and transcranial magnetic stimulation and pelvic floor strength were examined at the baseline and post-intervention at 1 month.

Results: Gynecological cancer survivors have more pelvic floor dysfunction that have a

relevant impact on HRQOL especially physical functioning compared to the healthy women. The exercise group had a significant improvement in pelvic floor dysfunction with comparison to the control group (p < 0.001). A significant short-term training effect was

rise in amplitude of motor evoked potential at sacral stimulation than in the control group.

Conclusions: Gynecological cancer and treatment procedures cause important problems

that have a negative effect on quality of life. Pelvic floor dysfunction improved after PFRP in gynecological cancer survivors. These preliminary results support the feasibility of a substantive trial of PFMT for pelvic floor dysfunction in gynecological cancer survivors.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

ABSTRACT ··· ⅰ TABLE OF CONTENTS ··· ⅲ LIST OF FIGURES ··· iv LIST OF TABLES ··· iv Ⅰ. INTRODUCTION ··· 1Ⅱ. MATERIALS AND METHODS ··· 5

A. Participations ··· 5

B. Methods··· 6

1. Pelvic Floor Rehabilitation Program Protocol ··· 6

2. Measurements ··· 9

3. Blinding ··· 12

4. Assessment of Exercise Adherence and Adverse Events ··· 13

5. Statistical Analyses··· 13

Ⅲ. Results ··· 15

A. Pelvic floor dysfunction and its impact on quality of life in gynecological cancer survivors··· 15

1. Comparison of pelvic floor symptom with reference group ··· 17

2. Relation of pelvic floor symptom with pelvic floor muscle strength and motor evoked potential ··· 21

3. Comparison of HRQOL outcomes with reference group ··· 23

cancer survivors ··· 27

1. Change in prevalence of pelvic floor dysfunction ··· 33

2. Changes in pelvic muscle strength and MEP ··· 35

3. Changes in HRQOL outcomes ··· 39

Ⅳ. DISCUSSION ··· 42

Ⅴ. CONCLUSION ··· 49

REFERENCES ··· 51

LIST OF FIGURES

Fig 1. Site of sacral stimulation ··· 11 Fig 2. Mean functional scores of patients with gynecological cancer compared with

reference group ··· 23 Fig 3. Mean symptom scores of patients with gynecological cancer compared with

reference group ··· 24 Fig 4. Flow chart of participants through the randomized controlled trial of the exercise

program and analysis ··· 32 Fig 5. Comparison changes of mean functional scores of exercise group compared with

control group in EORTC C-30 ··· 40 Fig 6. Comparison changes of mean functional and symptom scores of exercise group

LIST OF TABLES

Table 1. Demographic and disease-related characteristics of gynecological

cancer survivors and reference group ··· 16 Table 2. Prevalence of pelvic floor symptoms in gynecological cancer group

and reference group ··· 18 Table 3. Sexual questionnaire item analysis··· 19 Table 4. Comparison of pelvic muscle strength between incontinence and continence

group in gynecological cancer survivors ··· 22 Table 5. Relationship among generic HRQOL outcomes and pelvic

floor dysfunction ··· 26 Table 6. Baseline comparative characteristic between the two groups

in gynecological cancer survivors ··· 28 Table 7. Differences of prevalence in pelvic floor dysfunction between exercise

and control groups ··· 34 Table 8. Comparison of pelvic floor strength and MEP between exercise

I. INTRODUCTION

Gynecological cancers account for approximately 18% of all female cancers worldwide, and are a major source of mortality and morbidity. Most gynecological cancers show good survival rates; the 5-year survival rate for cervical cancer is 65% and endometrial cancer is 83% and these rates are increasing over time. Advances in surgical procedures (Trimbos, Maas et al. 2001), chemotherapy, and radiation have significantly reduced mortality from the major cancers of the female reproductive system, thus they have resulted in increased longevity. As cancer treatment improves, cancer survivor‟s quality of life and function have gained increasing importance. One important aspect of dysfunction directly impacted by gynecological cancer and treatment is pelvic floor dysfunction (PFD), which can severely affect patients‟ life(Herzog and Wright 2007) A wide range of PFD may be manifested as storage and voiding difficulties of the bladder (Benedetti-Panici, Zullo et al. 2004), urinary (Skjeldestad and Rannestad, 2009) or fecal incontinence(Sood, Nygaard et al. 2002, Dunberger et al., 2010), sexual problems (Vrzackpva et al., 2010) and pelvic or rectal pain. The operation of radical hysterectomy may result in partial denervation of inferior hypogastric plexus, the pudendal or sacral nerve(Jackson and Naik 2006). A series of studies demonstrated more severe clinical symptoms with a higher degree of PFD in irradiated compared with non-irradiated patients with gynecological cancer, particularly higher diarrhea, tenesmus and urgency.(Barker, Routledge et al. 2009)

negatively and despite high prevalence, they are under assessed in survivors of gynecological cancer. Evaluating HRQOL outcomes of PFD might be of great value as they inform about the disease burden and treatment-related effects directly from the patient‟s perspective. This also support clinical decision-making (Blazeby, Avery et al. 2006).

Pelvic floor muscles (PFM) are part of trunk stability mechanism and contribute to continence, elimination, sexual arousal and intra-abdominal pressure. When we consider the conservative approach for a certain disorder, less invasive and repeatable method with few side effects are selected preferentially (Konstantinidou, Apostolidis et al. 2007). Based on this principle, pelvic floor muscle training (PFMT) has been widely accepted as a first choice of treatment for the PFD (Elia and Bergman 1993) to improve the strength and efficacy of pelvic floor contraction.(Elia and Bergman 1993; Amuzu 1998; Yalcin, Hassa et al. 1998) (Bo, Talseth et al. 2000; Zahariou, Karamouti et al. 2008) But a low patient compliance (dropout rate of 39%) has been reported.(Yalcin, Hassa et al. 1998) To increase the compliance and control the correct contraction of the muscle, PFMT may also include the use of biofeedback in visualizing the strength and duration of any contraction (Hirsch, Weirauch et al. 1999) (Yamanishi, Sakakibara et al. 2000; Yamanishi, Yasuda et al. 2000). Recently, research has led to the synergy between the abdominal and PFM which presents the opportunity for different approach to the rehabilitation of pelvic floor dysfunction. Bladder neck elevation assessed with perineal ultrasound only occurred during PFM and abdominal muscle co-contraction(Junginger,

Baessler et al.). Sapsford et al.(Sapsford 2004) presented the rehabilitation program utilizing abdominal muscles action to initiate tonic PFM activity and to strength PFM and suggested appropriate training of PFM contraction for strength and co-ordination. The patient‟s motivation and compliance are essential for this treatment to be successful. Based on this understanding, we designed pelvic floor rehabilitation program (PFRP) to strengthen pelvic floor muscles utilizing trunk stabilization. By utilizing abdominal muscle action to initiate tonic pelvic floor muscle activity and biofeedback, patients can be aware of the contraction and corporate PFMT into daily living activities.

The pelvic floor musculature and sacral nerves are not easily accessible, and thus it‟s difficult to test them. While many functional assessments have been applied to evaluate pelvic floor dysfunction, the methodological literatures are sparse, and lack of consensus on their use is one of current issues. Functional outcome research is highly complex and consequently needs to be addressed in a comprehensive framework (Tschiesner, Chen et al. 2009) especially in the assessment of PFD of gynecological cancer survivors. The systematic outcome measurement tools including not only subjective self-reported PFD questionnaires and health-related quality of life but also objective measurement such as neurophysological testing for patients of suspected neurologic etiology (Lefaucheur 2006) or muscle strength testing for patients with weakened pelvic floor muscle are needed. To assess the influence of gynecological cancer on pelvic floor dysfunction and the therapeutic response to PFRP in more detail, we evaluated clinical, functional and neurophysiological features in gynecological

cancer survivors and prospectively followed and compared them for short-term training effects.

This study‟s goals were to evaluate the PFD and its impact on quality of life in gynecological cancer survivors and to design a pelvic floor rehabilitation program (PFRP) and to investigate the effectiveness of the PFRP on pelvic floor function and quality of life in gynecological cancer survivors by a prospective randomized controlled trial.

Ⅱ. MATERIALS AND METHODS

A. Participants

Women with cervical cancer and endometrial cancer who had radical hysterectomy and pelvic lymph node dissection between July 2009 and December 2009 were recruited among the patients who registered at cancer clinics at Seoul National University Bundang Hospital, Korea. All participants were 20 years or older and were able to give an informed consent and to comply with instructions to use a biofeedback device. We confined study participants to patients who had no infectious disease in the urinary tract and vagina, because PFMT with biofeedback device was not available for them. Among 50 subjects who met the inclusion criteria, 6 refused to participate in the study because of time constraints or unwillingness to visit the clinic. Ten subjects were excluded because they had unstable medical conditions such as fever, anemia at the time of baseline measurement. To assess the prevalence of pelvic floor disorders in gynecologic cancer survivors compared with healthy women who had no history of a gynecologic cancer, women who were >20 years old without a diagnosis of cancer were recruited. We matched for age (maximal difference of 3 years), being nulli- or multiparous, and BMI. Finally, 34 subjects with gynecological cancer and 16 health women agreed to participate (reference group) and completed Korean version of pelvic floor questionnaire and Korean version of the EORTC QLQ-C30 and QLQ-CX24. All participants provided written informed consent. This study complied with the Declaration of Helsinki, and its protocol was approved by the institutional review board of Seoul National University,

Bundang Hospital.

Participants were randomly allocated to exercise group comprising intensive pelvic floor muscle training incorporated with core exercise or control group by the computerized stratified block randomization procedure allocating participants according to cancer stage and age. The subjects were identified by means of 2 levels of 2 strata: stratum 1, cancer stage 1, 2 or 3, 4, and stratum 2, age < 50 and 50 years. They were assigned into two groups so that the number of subjects in each stratum was approximately equal in the 2 groups.

B. Methods

1. Pelvic Floor Rehabilitation Program (PFRP) Protocol

The pelvic floor rehabilitation program (PFRP) was designed with 45-minute duration per session, once per week, for 4 weeks. The standardized intervention given to women in exercise group consisted of six appointments with a specialist and a physiotherapist over a 4-week period (at weeks 0, 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5). At the first visit, the history of cancer treatment was taken, and both subjective pelvic floor dysfunction assessment and objective internal pelvic floor function measurement were carried out. Patients learned anatomy and function of the pelvic floor muscles and how to correctly contract the pelvic floor muscles. The PFRP consisted of biofeedback sessions and core exercise sessions. After supervised instruction, patients were taught PFM exercise via biofeedback (BioCon-200, mcubetech inc, Seoul, Korea). Biofeedback was performed in lithotomy

position via a vaginal silicon pressure sensor (Pathway™ Vaginal Silicon Pressure Sensor , THE PROMETHEUS GROUP, Dover, USA). A two-channel EMG biofeedback apparatus was used, with all channels for rectus abdominal muscles, and the signal received through surface electrodes

During the initial two to three sessions, a strong emphasis was placed on the specificity of muscle contraction (isolated contraction of the pelvic muscles with the minimum possible activity of the rectus abdominal muscles). Every session lasted 20 min and consisted of 40 cycles with 10s activity followed by 20s of relaxation. After 5 min of resting period, patients received 20-minute intensive core exercise session consisted of strengthening exercises for the pelvic floor muscles and transverse abdominus muscles and of stretching exercises for muscles attached to the pelvic girdle such as gluteus, tensor fascia latae, piriformis muscles and adductors and surrounding ligaments according to Evjenth and Hamberg (Blomberg, Svardsudd et al. 1992) under the supervision by physical therapists. Diaghragmatic breathing techniques were taught as an important part of the core-strengthening program and abdominal hollowing was also performed to activate the transversus abdominis (McGill 2001) One trained evaluator conducted all the evaluation of PFMT.

In once a week visits for 4 weeks, 30 min counseling and an individualized home exercise program were provided after PFRP. Patients were encouraged to perform six sets of exercises daily (one set consisted of up to ten maximum voluntary contractions held

for up to 10 s, with 4 s rest between each contractionand, after a one minute rest, ten or more fast contractions), with the use of an exercise diary. Changes of symptoms, compliance with the advices for lifestyle modification and changes in pelvic floor muscle strength measured by vaginal pressure sensor were recorded at each visit. The content of the home exercise program adjusted to the conditions of the subjects. Eventually, we developed a comprehensive functional program consisting of all components including teaching of pelvic floor exercises, pelvic floor muscle assessment, lifestyle advices and the encouragement of home based exercises. Furthermore, standardized clinical documents, exercise diaries and leaflets were used to ensure systematic approach and consistent outcome.

Patients in control group were taught in detail about the methods of constricting their pelvic muscles, with special emphasis on avoiding constricting the abdominal muscles simultaneously. Verbal guidance and feedback of the contractions were used to instruct the patient how to correctly and selectively contract the anal sphincter while relaxing the abdominal muscles. They were advised to practice for 20 minutes per day five times a week. The exercise session was designed to include short and long duration exercises. In addition, these patients received an informative leaflet with these instructions and a telephone number for further explanations. The leaflet identical to that given to the intervention group was provided. The control group did not see a physiotherapist and had no planned visit of the hospital by the follow-up appointment.

2. Measurements

The outcome measures were (1) pelvic floor dysfunction questionnaire, (2) pelvic floor muscle strength, (3) motor evoked potential of pudendal nerve, and (4) patient-reported HRQOL Quality of life measured by the Korean Version of the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life core questionnaire (EORTC QLQ-C30) and the Korean Version of the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire Cervical Cancer Module (EORTC QLQ-CX-24). All outcomes were measured as changes from completion at the 5 weeks assessment to baseline.

Pelvic floor dysfunction questionnaire

Subjective quotients in pelvic floor dysfunction were assessed from the interview based evaluation. All participants completed the interviewer-administered pelvic floor questionnaire (Baessler, O'Neill et al. 2009) This tool encompassed all aspects of pelvic floor function including condition-specific quality of life issues and bothersome symptoms in a reproducible and valid fashion. The questionnaires contained the questions on bladder, bowel and sexual symptoms and impact on quality of life. To assess frequency, severity of pelvic floor symptoms, a 4-point scoring system was used for most items of the questionnaires except for defecation frequency, bowel consistency, sufficient lubrication, and the reason for sexual abstinence. Answers to above 4 questions did not allow for a graded, interval-scaled scoring system. Cronbach‟s alpha coefficients were

acceptable in all domains: bladder function 0.72, bowel function 0.82 and sexual function 0.81(Baessler, O'Neill et al. 2009) . Kappa coefficients of agreement for test-retest analyses varied from 0.5 to 1.0 (Baessler, O'Neill et al. 2009).

Pelvic floor muscle strength

The PFM strength was measured by perineometry prior to and after 4 weeks treatment. Vaginal pressure was then measured using a vaginal silicon pressure sensor perineometer (sensitivity 0.06 kPa, sensitivity 5 mV, threshold 1.5 V). Perineometer is a dynamometry which is used for the assessment of PFM strength objectively. This perineometer uses cms/H2O. The probe is inserted 3-3.5 cm into the vagina, and the patient is instructed to contract the PFM in the same dorsal position. All measurements were carried out by the same evaluator, who also observed the woman to ensure she wasn‟t „straining‟ the pelvic floor during the procedure.

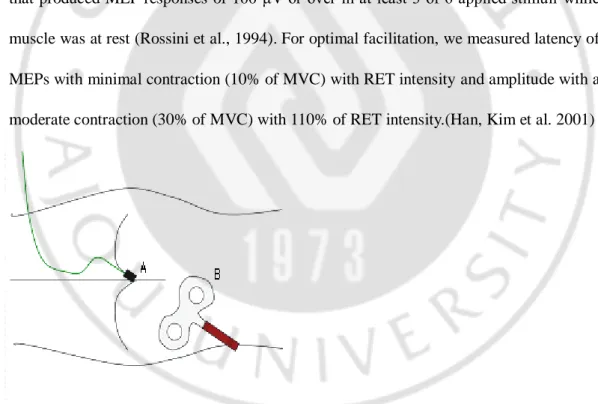

Motor evoked potential of pudendal nerve

The motor evoked potential (MEP) from pelvic floor was obtained by sacral and transcranial magnetic stimulation (Magstim 200, UK) at baseline and follow-up after 4 weeks treatment. Patients lied in the left lateral decubitus position. Specially designed intra-anal sponge electrode (Dantec, Skovlund, Denmark) was lubricated and gently placed into the anal canal. Monophasic single pulses of magnetic stimuli were delivered by a double cone coil (9902-00, Magstim, UK) at the vertex corresponding to the

primary motor center in the precentral gyrus. Figure-of-8 coil (9762-00, Magstim, UK) was used to stimulate the dorso-laterally over the side sacrum corresponding to the exit of the sacral nerves from the sacral bone (Fig 1). To evaluate the cortical facilitation, we recorded MEPs in two conditions: with the relaxation of the target muscles and with the voluntary contraction moderately to maximally. We measured latency, amplitude and excitability threshold (ET) of MEPs detected from pelvic floor muscles without and with facilitation. The excitability threshold at rest (RET) was defined as the lowest intensity that produced MEP responses of 100 μV or over in at least 3 of 6 applied stimuli while muscle was at rest (Rossini et al., 1994). For optimal facilitation, we measured latency of MEPs with minimal contraction (10% of MVC) with RET intensity and amplitude with a moderate contraction (30% of MVC) with 110% of RET intensity.(Han, Kim et al. 2001)

Fig 1. Site of sacral stimulation A: intra-anal sponge electrode (Dantec, Skovlund,

Patient-reported HRQOL Quality of life

Generic and condition-specific HRQOL aspects were assessed with the EORTC QLQ-C30 and QLQ-CX24 questionnaire (Yun, Park et al. 2004) (Shin, Ahn et al. 2009). The EORTC QLQ-C30 is a multidimensional questionnaire for cancer patients containing 30 items grouped into one global health status/QOL scale, five functional scales (physical, role, emotional, cognitive and social functioning), three symptom scales (fatigue, pain and nausea and vomiting) and six single-item scales (dyspnea, insomnia, appetite loss, constipation, diarrhea and financial difficulties)(Aaronson, Ahmedzai et al. 1993). The specific cervical cancer module (QLQ-CX24) (Shin, Ahn et al. 2009) consists of 3 multi-item and 6 single-item scales and examines 3 variables that are not sufficiently addressed by the core instrument (i.e. subjects‟ symptom experience, body image and sexuality).

3. Blinding

Blinding of participants was not possible because of the nature of the interventions. Training sessions and strength measurements were administered by different persons so that knowledge of an individual‟s training progression would not influence the process of measurement and vice versa. Outcome evaluators were also blinded to group allocation of participants.

4. Assessment of Exercise Adherence and Adverse Events

A physical therapist and trained evaluator monitored adherence and adverse effects. The subjects who experienced aggravation of pelvic floor symptoms and/or had some difficulty in continuing to do the exercise because of some other cause were excluded from the final assessment.

5. Statistical Analyses

Data was presented as mean (SD) or median (25th to 75th percentiles) according distribution. The differences in the baseline data between the groups were analyzed using t-test and the non-parametric Mann-Whitney test for the continuous variables with and without a normal distribution, respectively and chi-square test for the categorical variables.

The EORTC QLQ-C30 and the QLQ-CX24 scores were calculated using the recommended EORTC procedure (Fayers, Aaronson et al. 1999). The means were compared and interpreted following previous findings indicating that the difference of at least 10 points could be considered as a clinically meaningful change (Osoba, Rodrigues et al. 1998). In order to evaluate the impact of pelvic floor dysfunction on HRQOL scales, univariate linear regression analysis was used.

Difference scores (5weeks, baseline) constructed in for all variables were used to assess the changes. The changes of dependent variables between pre-intervention and post-intervention in the exercise and control group were analyzed using an analysis of

variance (ANOVA) with repeated measures. Within-group comparisons were made using paired t-test or Wilcoxon rank sign test. For categorical dichotomous variables the Mac Nemar test was used, while the Marginal Homogeneity test was used for categorical variables with more than two categories.

Ⅲ. RESULTS

A. Pelvic floor dysfunction and its impact on quality of life in gynecological cancer survivors

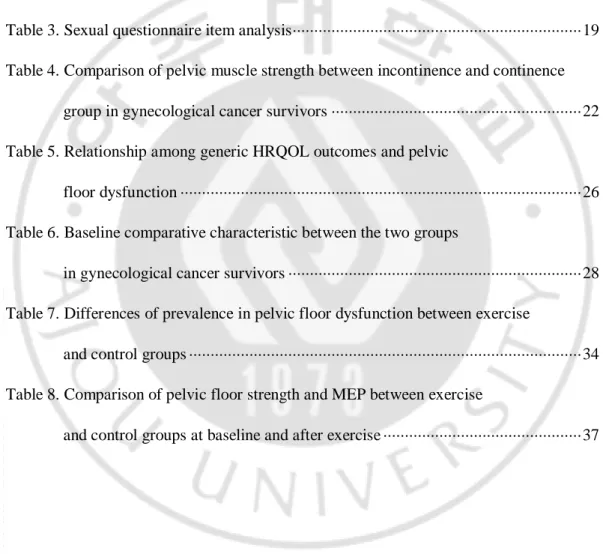

There were no significant differences between the groups in the baseline characteristics such as age, marital status, multiparous and level of education (Table 1). Statistically significant difference was noted between the groups in the employment status (p=0.003). Mean age of 34 participants who underwent the initial evaluation and 16 reference group were 51.5 ± 8.3 years (range, 35-67 years) and 51.8 ± 8.3 years (range, 39-61 years). In the gynecological cancer group, 30 women were cervical cancer survivors and 4 women were endometrial cancer survivors. Twenty percent of gynecological cancer survivors had early-stage disease. Median interval between cancer treatment and baseline assessment was 1.2 years (range 1 to 5 years). Two women had been treated with radical hysterectomy and pelvic lymph node dissection only, 10 underwent surgery and adjuvant radiotherapy, 13 underwent surgery and adjuvant chemotherapy and 9 underwent surgery and adjuvant chemoradiotherapy.

Table 1 Demographic and disease-related characteristics of gynecological cancer survivors and reference group

Gynecologic al cancer group (n=34)

Reference group (n=16) P value

Demographic Age 51.5 ± 8.3 51.8 ± 8.3 0.783 Marital status 0.580 Married 33 15 Unmarried 1 1 Multiparous 29 13 0.083 Level of education 0.063 >12 years 26 16 <12 years 8 0 Employment status 0.003 Employed 5 9 Unemployed 29 7 Disease related Cancer type Cervical cancer 30 Endometrial cancer 4 FIGO stage Ⅰ 7 Ⅱ-Ⅳa 27

Time since treatment (years, range) 1.2 (1-5) Treatment type Surgery only 2 Surgery + radiotherapy 10 Surgery +chemotherapy 13 Surgery + radiotherapy +chemotherapy 9

1. Comparison of pelvic floor symptom with reference group

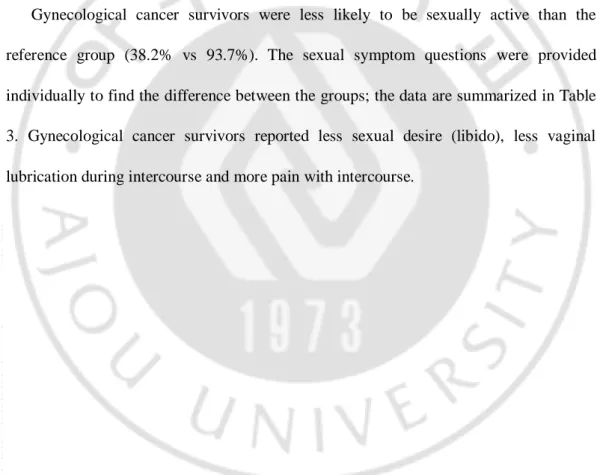

Table 2 displays the pelvic floor symptoms in gynecological cancer group and reference group. In the urinary symptoms, gynecological cancer patients showed significantly higher rate of urinary frequency, nocturia and stress incontinence. In bowel symptoms, gynecological cancer group showed significantly higher rate of straining, urgency and incomplete emptying stool than the reference group.

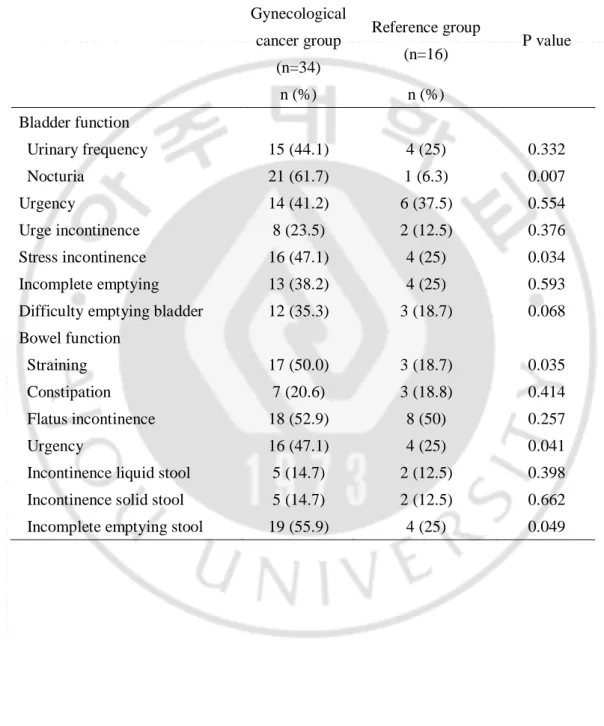

Gynecological cancer survivors were less likely to be sexually active than the reference group (38.2% vs 93.7%). The sexual symptom questions were provided individually to find the difference between the groups; the data are summarized in Table 3. Gynecological cancer survivors reported less sexual desire (libido), less vaginal lubrication during intercourse and more pain with intercourse.

Table 2-1. Pelvic floor dysfunction in gynecological cancer group and reference group Gynecological cancer group (n=34) Reference group (n=16) P value n (%) n (%) Bladder function Urinary frequency 15 (44.1) 4 (25) 0.332 Nocturia 21 (61.7) 1 (6.3) 0.007 Urgency 14 (41.2) 6 (37.5) 0.554 Urge incontinence 8 (23.5) 2 (12.5) 0.376 Stress incontinence 16 (47.1) 4 (25) 0.034 Incomplete emptying 13 (38.2) 4 (25) 0.593 Difficulty emptying bladder 12 (35.3) 3 (18.7) 0.068 Bowel function

Straining 17 (50.0) 3 (18.7) 0.035

Constipation 7 (20.6) 3 (18.8) 0.414

Flatus incontinence 18 (52.9) 8 (50) 0.257

Urgency 16 (47.1) 4 (25) 0.041

Incontinence liquid stool 5 (14.7) 2 (12.5) 0.398 Incontinence solid stool 5 (14.7) 2 (12.5) 0.662 Incomplete emptying stool 19 (55.9) 4 (25) 0.049

Table 3. Sexual questionnaire item analysis Gynecological cancer group (n=34) Reference group (n=16) P value How would you describe your level of sexual interest during the past month (libido)?

None 13 2

Low 6 9

Moderate 5 5

High

How often do you have sex?

Never 21 1

Occasionally (<1/week) 11 13 Frequently(>1/week) 2 2 Most days

If not, why not?

No partner 2 1

No interest 8 Partner unable 3 Painful/vaginal dryness 6 Uncomfortable from incontinence 2

How often do you have an orgasm?

3 Seldom 1 0.215

2 Sometimes 10 6

1 Usually 3 6

0 Always 2

During intercourse, vaginal sensation is:

3 None 4 1 0.237

2 Minimal 6 6

1 Pleasant 3 6

Do you have sufficient natural vaginal lubrication during intercourse?

0 Yes 4 13 0.022

1 No 9 2

Do you experience pain with intercourse?

0 Never 2 10 0.008

1 Occasionally 3 5

2 Frequently 5

3 Always 3

Is sexual intercourse enjoyable for you?

3 Not at all 5 3 0.09

2 Occasionally 8 5

1 Frequently 6

2. Relation of pelvic floor symptoms with pelvic floor muscle strength and MEP

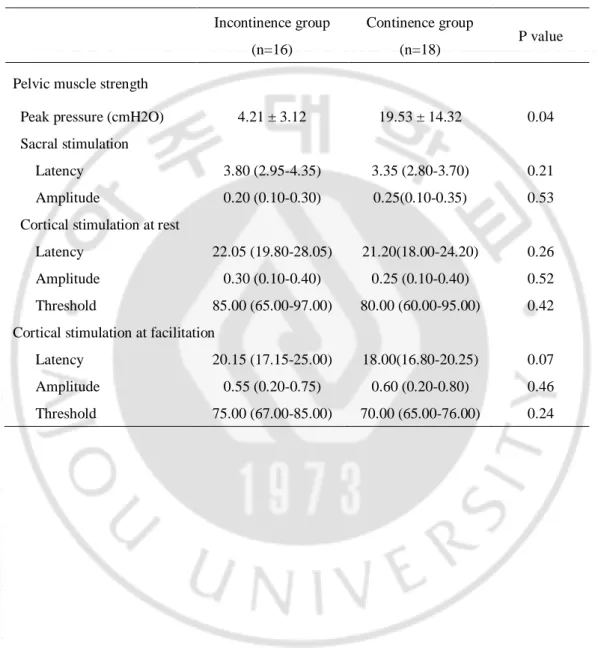

Subsequently, we divided the gynecological cancer survivors in two subgroups according to whether the urinary incontinence or not: incontinence group and continence group and compared the pelvic floor strength and MEP. In incontinence group, pelvic floor muscle strength is significantly weaker than that in continence group (4.21 vs 19.53, P = 0.04). We obtained motor evoked responses in only five patients of incontinence group, but in twelve patients of continence gorup with all the stimulations (cord, cortical and sacral plexus, respectively). Two in incontinence group and six in continence group showed motor evoked potential with stimulation on only one side of sacral plexus and the potential could evoked with cortical stimulation at the same cases. The latency with cortical stimulation with facilitation in incontinence group was more delayed compared to that in the continence group, but not significantly (p=0.07) (Table 4). One in incontinence group showed no motor evoked potential by sacral stimulation and cortical stimulation at rest, but by cortical stimulation with facilitation, the potential was evoked (latency 19.60 ms, amplitude 0.50 mV, CET 100%). Interestingly, five of them had lymphedema at the same side where the potentials were not provoked. Other participants we could not evoked motor responses at any stimulation.

Table 4. Comparison of pelvic muscle strength between incontinence and continence group in gynecological cancer survivors

Incontinence group (n=16)

Continence group

(n=18) P value Pelvic muscle strength

Peak pressure (cmH2O) 4.21 ± 3.12 19.53 ± 14.32 0.04 Sacral stimulation

Latency 3.80 (2.95-4.35) 3.35 (2.80-3.70) 0.21 Amplitude 0.20 (0.10-0.30) 0.25(0.10-0.35) 0.53 Cortical stimulation at rest

Latency 22.05 (19.80-28.05) 21.20(18.00-24.20) 0.26 Amplitude 0.30 (0.10-0.40) 0.25 (0.10-0.40) 0.52 Threshold 85.00 (65.00-97.00) 80.00 (60.00-95.00) 0.42 Cortical stimulation at facilitation

Latency 20.15 (17.15-25.00) 18.00(16.80-20.25) 0.07 Amplitude 0.55 (0.20-0.75) 0.60 (0.20-0.80) 0.46 Threshold 75.00 (67.00-85.00) 70.00 (65.00-76.00) 0.24

0 20 40 60 80 100 120 Physical functioning Role functioning Emotional functioning Cognitive functioning Social functioning Global Health M e a n s c ore Gynecological cancer Reference group

*

*

*

3. Comparison of HRQOL outcomes with reference groupClinically meaningful differences (10 points) were observed between gynecological cancer patients and healthy controls in terms of physical functioning (71.7 vs 84.6), social functioning (79.2 vs 95.8) and global health status (52.6 vs 75.7) (Fig 2).

Fig 2. Mean functional scores of patients with gynecological cancer compared with reference group. A higher score represents a higher level of functioning or global

health status/QOL. *Differences in health-related quality of life scores between groups were considered clinically relevant if 10 points

0 5 10 15 20 25 30 35 40 45

Fatigue Nausea/vomitting Pain Dyspnea Insomnia Appetite loss Constipation Diarrhea Financial difficulties M e a n S c o re Gynecological cancer Reference group * * *

As for symptom-related showed remarkably worse outcomes in terms of constipation (38.8 vs 8.3), diarrhea (33.3 vs 18.7) and financial difficulties (24.2 vs 4.2) (fig 3).

Fig 3. Mean symptom scores of patients with gynecological cancer compared with reference group. A higher score represents a higher perception

of the symptom. *Differences in health-related quality of life scores between groups were considered clinically relevant if 10 points

4. Impact of pelvic floor dysfunction on cancer generic HRQOL outcomes (EORTC QLQ-C30)

There was a strong association between functional scales and bladder and bowel function-related covariates. Urinary urgency negatively affected physical functioning (p=0.003), role functioning (p=0.005) and social functioning (0=0.007) and urinary incontinence negatively associated with the global health status/QOL (p=0.021) and physical functioning (p=0.024). Difficulty emptying negatively affected the global health status/QOL (p=0.019) and social functioning (p=0.034). Incomplete evacuation was negatively associated with the physical functioning (p=0.007). Sexual inactivity negatively affected the global health status/QOL (p=0.021) (Table 5). No variables were associated with emotional functioning (data no shown).

Table 5. Relationship among generic (EORTC QLQ-C30) HRQOL outcomes and pelvic floor dysfunction

Clinical variables Global health status QOL Physical functioning Role functioning Social functioning Urinary frequency: yes

vs. no -1.41 -11.67 -9.09 -1.41

Urinary urgency: yes vs.

no -1.86 -6.39* -8.75* -5.73*

Urinary incontinence: yes

vs. no -5.73* -7.33* -7.18 -1.86

Nocturia: yes vs. no -2.27 -1.85 -3.71 -2.27

Incomplete emptying:

yes vs. no 5.35 -4.65 5.24 5.35

Difficult emptying: yes

vs. no -6.54* -2.56 1.09 -6.24*

Stool urgency: yes vs. no -2.78 3.33 -7.59 -2.78 Incontinence of solid stool: yes vs. no -1.41 -9.01 -4.17 -1.41 Incomplete evacuation: yes vs. no -0.34 -9.51* -4.89 -0.34 Sexual activity: no vs. yes -5.42* -1.75 -2.45 -2.53

Univariate regression analysis: regression coefficients

EORTC European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer, QOL Quality of life, HRQOL health-related quality of life

B. Effectiveness of Pelvic Floor Rehabilitation Program for gynecological cancer survivor

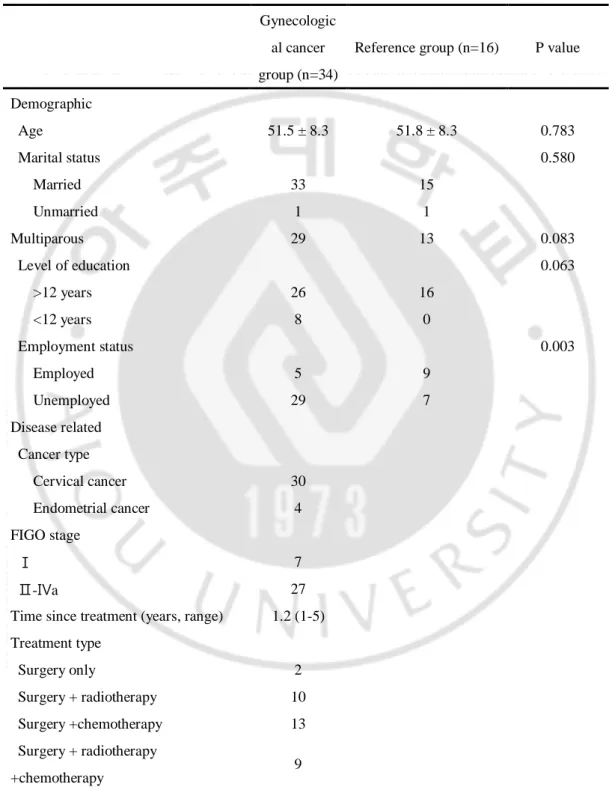

There were no significant differences between exercise and control groups in any of the baseline characteristics (Table 6). No significant difference in the participants‟ ages was found between the intervention and control groups at baseline. The proportions of marriage, education level and employment status were not significantly different between the groups. A diagnosis of stage 1 disease had been made in 20% and 18.1%, and 10% and 9.1% had undergone surgery without additional treatments respectively. Before beginning the exercise programs, pelvic floor strength measured by perineometer were 12.8 ±16.6 and 11.3 ± 9.9, No differences were found in the baseline latencies and amplitudes of pudendal motor nerve stimulating at cortical area, cord and sacral plexus among groups. We only obtained motor evoked responses in eight patients in exercise group and nine patients in control group at baseline assessment. Other participants we could not evoked motor responses with magnetic stimulation.

Table 6-1. Baseline comparative characteristics between the two groups in gynecological cancer survivors

Group P value

Exercise group (n=17) Control group (n=17) Age (years) 51.8 ± 8.3 52.1 ± 8.9 0.513 Marital status 0.500 Married 17 16 Unmarried 0 1 Level of education 0.326 12 years 14 12 <12 years 3 5 Employment status 0.500 Employed 3 2 Unemployed 14 15 Cancer Cervical cancer 15 15 0.500 Endometrial cancer 2 2 FIGO stage 0.500 Ⅰ 3 4 Ⅱ-Ⅳa 14 13

Time since treatment

(years) 1.2 1.3 0.821 Treatment 0.765 Surgery only 1 1 Surgery + radiotherapy 5 5 Surgery +chemotherapy 7 6 Surgery + radiotherapy +chemotherapy 4 5

Table 6-2. Baseline comparative pelvic floor function between the two groups in gynecological cancer survivors

Group P value

Exercise group (n=17) Control group (n=17) Pelvic floor questionnaire

Bladder score 1.98 ± 1.71 1.41 ± 1.25 0.51 Bowel score 1.83 ± 1.02 1.28 ± 1.32 0.23 Sex score 6.18 ± 2.62 4.30 ± 3.30 0.67 Pelvic floor muscle

strength (cm/H2O) 12.78 ± 16.57 11.32 ± 9.91 0.543 Motor evoked potential

Cord Stimulation Latency 3.8 (3.1-3.9) 4.4 (3.9-6.9) 0.08 Amplitude 0.3 (0.1-0.7) 0.3 (0.1-0.5) 0.9 Sacral stimulation Latency 3.4 (3.1-3.7) 3.3 (3.0-3.6) 0.69 Amplitude 0.1 (0.1-.0.1) 0.1 (0.1-0.2) 0.47 Cranial stimulation at rest Latency 23.4 (19.0-26.1) 24.2 (21.1-26.6) 0.21 Amplitude 0.4 (0.1-0.5) 0.2 (0.1-0.2) 0.72 Threshold 70.0 (65.0-77.5) 78.0 (71.3-100.0) 0.25 Cranial stimulation with facilitation Latency 19.2 (18.3-22.2) 20.9 (20.1-24.8) 0.13 Amplitude 0.5 (0.2-0.7) 0.3 (0.1-0.4) 0.32 Threshold 65.0 (35.0-77.5) 70.0 (70.0-80.0) 0.22

Table 6-3. Baseline comparative quality of life between the two groups in gynecological cancer survivors

Group P value

Exercise group (n=17) Control group (n=17) EORTC QLQ C30

Global health status 52.78 ± 19.98 52.50 ± 14.19 0.72 Physical functioning 76.30 ± 18.29 67.88 ± 17.84 0.33 Role functioning 79.63 ± 23.24 74.24 ± 18.80 0.51 Emotional functioning 72.22 ± 14.43 65.15 ± 20.69 0.46 Cognitive functioning 79.63 ± 11.11 75.76 ± 15.57 0.71 Social functioning 87.04 ± 16.20 72.73 ± 23.89 0.21 Fatigue 32.10 ± 17.07 37.37 ± 24.48 0.65 Nausea & Vomitting 0.00 ± 0.00 6.06 ± 11.24 0.33 Pain 22.22 ± 22.05 19.70 ± 23.36 0.77 Dyspnea 11.11 ± 16.67 12.12 ± 23.36 0.94 Insomnia 25.93 ± 36.43 27.27 ± 35.96 0.93 Loss of appetite 0.00 ± 0.00 3.03 ± 10.05 0.77 Constipation 14.81 ± 17.51 9.09 ± 21.56 0.53 Diarrhea 11.11 ± 16.67 6.06 ± 13.48 0.37 EORTC QLQ CX-24 Lymphedema 33.33 ± 28.87 42.42 ± 30.15 0.63 Peripheral neuropathy 14.81 ± 24.22 9.09 ± 21.56 0.61 Symptom experience 12.46 ± 4.13 11.57 ± 8.66 0.33 Menopausal symptom 33.33 ± 25.20 33.33 ± 33.33 0.91 Body image 48.61 ± 19.64 39.39 ± 27.83 0.44 Sexual worry 44.44 ± 18.78 37.50 ± 45.21 0.39 Sexual activity 19.05 ± 17.82 20.83 ± 17.25 0.33 Sexual enjoyment 12.50 ± 4.23 19.05 ± 17.82 0.75

Thirty-four participants who underwent the initial evaluation were randomly allocated into 2 groups: 17 subjects were assigned to the exercise group, and 17 to the control group. Before they began to do exercises, three women from exercise group and three women from control group failed to appear in the program session for personal reasons.

Two patients from the each group were dropped out during the intervention. Finally, 12 and 12 participants in the exercise and control groups, respectively, completed the interventions and the follow-up evaluations (Fig 4).

Gynecological cancer met eligible criteria and gave informed consent (n=34) Assigned to exercise group (n=17) Baseline: Control (n=14) Completed 4 week follow-up (n=12) Completed 4 week follow-up (n=12) Gynecological cancer survivors recruited (n=45) Randomization 2 Dropouts:

•Poor general condition (n=1) •Recurred cancer (n=1)

Exclusion (n=11) after initial assessments

• Recurred cancer (n=2) • Not adequate subjects (n=3) • Refuse to consent (n=6)

Assigned to control group (n=17)

Withdrawal (n=3) •Other therapy schedule •Change in mind

Baseline: Exercise (n=14)

Withdrawal (n=3) •Other therapy schedule •Change in mind

2 Dropouts:

•Incomplete participation(n=1) •Poor general condition (n=1)

Fig 4 Flow chart of participants through the randomized controlled trial of the exercise program and analysis.

1. Changes in frequency of pelvic floor dysfunction

Stress incontinence was decreased from 64.3% to 33.3% after the intervention in the exercise group (p=0.036). Urinary urgency was decreased from 57.1% to 33.3% after the intervention in the exercise group (p=0.042). Flatus incontinence was decreased from 57.1 % at the baseline to 25.0 % after the intervention in the exercise group (p=0.033) and defecation urgency was decreased from 42.9% to 16.7% after the intervention in the exercise group (p=0.027). But these variables revealed no statistically changes between before and after the intervention in control group. The comparison of changes in prevalence of stress incontinence and flatus incontinence revealed significantly difference between the exercise and control group, but the changes of urinary and defecation urgency were not significantly different between the groups. (Table 7). The proportion of sexually active women increased from 41.7 % at the baseline to 75.0 % after intervention in the exercise group, whereas the change was not significant in the control group. The comparison of changes in prevalence of sexually active women revealed significantly difference between the exercise and control group.

Table 7. Difference of prevalence in pelvic floor dysfunction between exercise and control groups

Exercise group Control group Differences in proportion Baseline Follow-up Baseline Follow-up Exercise Control

Bladder function Urinary frequency 50.0 41.7 57.1 58.3 -8.3 1.2 Nocturia 92.8 83.3 57.1 41.7 -9.5 -5.4 Urgency 57.1* 33.3* 42.9 33.3 -23.8 -9.6 Urge incontinence 21.3 16.7 35.7 33.3 -4.6 -2.4 Stress incontinence 64.3 * 33.3* 50.0 41.7 -31.0 -8.3 Incomplete emptying 35.7 33.3 57.1 41.7 -2.4 -15.4 Difficulty emptying bladder 35.7 25.0 50.0 58.3 -10.7 8.3 Bowel function Straining 57.1 41.7 64.3 58.3 -15.4 -6.0 Constipation 28.6 25.0 21.4 16.7 -3.6 -4.7 Flatus incontinence 57.1 * 25.0* 71.4 58.3 -32.1 -13.1 Urgency 42.9* 16.7* 71.4 58.3 -26.2 -13.1 Incontinence liquid stool 14.3 16.7 21.4 16.7 2.4 -4.7 Incontinence solid stool 28.6 25.0 14.3 16.7 -3.6 2.4 Incomplete emptying stool 78.6 66.7 57.1 41.7 -11.9 -15.3 Sexual function Sexual activity 41.7 75.0 38.2 43.5 33.8 5.6

2. Changes in pelvic muscle strength and MEP

Pelvic floor muscle strength significantly increased after the exercise programs (from 12.8 cmH2O to 31.5 cmH2O; p = .02). Compared with the control group, exercise group resulted in significantly increase in pelvic floor muscle strength (p=0.028) (Table 8)

The amplitude of pudendal nerve motor evoked potentials (MEPs) to sacral stimulation increased slightly (From 0.12 mV to 0.32 mV) and the excitability threshold to sacral stimulation significantly decreased after exercise program (From 93% to 67%), but these variables were not significantly changed in the control group. The comparison of changes in amplitude and threshold to sacral stimulation revealed significantly difference between the exercise and control group.

The resting excitability threshold at rest (RET) and contraction (CET) significantly decreased after the exercise program. The reductions in RET were 14.6% and 2.1% in the exercise and control group, respectively. CET decreased by 16.7% in the exercise group, which reflected statistically significant changes between before and after the intervention, but the change was not significantly different in the control group. The latency of MEPs to cortical stimulation with contraction of pelvic floor muscle in the exercise group decreased significantly after exercise (20.25 ms to 18.58 ms, P = 0.04). The changes of the latencies of MEP after muscle contraction from that at rest became significantly larger after exercise in the exercise group. The amplitude of MEPs to cortical stimulation with contraction of pelvic floor muscle in the exercise group increased significantly

(from 0.38 mV to 0.59 mV, P = 0.04), but the comparison of changes revealed no difference between the exercise and control group.

Table 8. Comparison of pelvic floor strength and motor evoked potential between exercise and control groups at baseline and after one month exercise

Exercise group Control group Differences

Baseline Follow-up P Baseline Follow-up P Exercise Control P

Pelvic floor muscle strength Peak pressure (cmH2O) 12.83 31.51 0.02 11.33 20.42 0.68 21.24 12.11(2.0-26.0) 0.03 Cord stimulation Latency 3.81(3.12-3.89) 3.78(3.57-3.91) 0.23 3.93(3.62-6.89) 4.02(3.78-4.45) 0.13 -0.02 0.03 0.85 Amplitude 0.32(0.12-0.67) 0.47(0.39-1.24) 0.41 0.25(0.11-0.52) 0.32 (0.21-0.68) 0.87 0.29 (-0.30-1.15) 0.10(-0.02-0.35) 0.25 Sacral stimulation Latency 3.36(3.11-3.73) 3.43(3.18-3.49) 0.08 3.31(3.01-3.64) 3.43(3.31-3.62) 0.47 -0.63(-1.30-0.05) -0.63 (-7.35-0.10) 0.56 Amplitude 0.12(0.11-.0.18) 0.32(0.26-0.61) 0.02 0.11(0.12-0.21) 0.12(0.11-0.53) 0.66 0.25(0.15-0.55) 0.01(-0.10-0.12) 0.01 Threshold 93.03(86.00-97.00) 67.52(47.52-80) 0.03 85.00(75.0-100) 84.04(63.52-100) 0.29 -24.76(-42.11--9.02) -1.02(-0.04-5.06) 0.04

Cortical stimulation at rest

Latency 23.41(19.02-26.13) 22.06(18.68-24.52) 0.49 24.21(21.12-26.62) 23.15(20.27-25.21) 0.47 -0.81 (-0.80-2.08) -0.95(-1.80-0.08) 0.44 Amplitude 0.21(0.14-0.57) 0.24(0.12-0.42) 0.12 0.22(0.14-0.32) 0.24(0.16-0.35) 0.79 0.03(-0.20-0.30) 0.02(-0.12-0.21) 0.88 Threshold 76.64(65.02-77.53) 59.71(50.02- 0.03 78.01(71.28-100.00) 76.12(53.02- 0.86 -14.57(-36.50- -2.02(-35.02- 0.03

65.02) 100.00) 25.00) 20.02) Cortical stimulation with facilitation

Latency 20.25(18.33-23.42) 18.58(17.15-21.03) 0.04 20.89(20.13-24.82) 20.00(17.72-22.11) 0.25 -1.73(-0.95~19.82) -0.67(-20.45-1.95) 0.04 Amplitude 0.38(0.17-0.59) 0.59(0.52-1.01) 0.04 0.33(0.12-0.42) 0.42(0.13-0.45) 0.34 0.19(-0.30~0.70) 0.11(0.02-0.21) 0.47 Threshold 65.02(35.01-77.53) 50.02(40.02-67.52) 0.04 70.00(70.02-80.02) 65.02(50.51-92.45) 0.92 -16.67(-3.85-45.01) -5.18(-70.02-3.02) 0.03

3. Changes in HRQOL outcomes

Clinical meaningful differences (10 points) (Salvatore P et al., 2009) were observed between before and after intervention in the exercise group in terms of physical functioning, sexual worry, sexual activity and sexual/vaginal functioning (66.9 vs 80.3. P = 0.03; 42.3 vs 20.7 P = 0.04; 19.1 vs 30.5 P = 0.02; and 12.5 vs 27.1, P = 0.04 respectively). The comparison changes of these variables revealed significant difference between the exercise and control group. Improvements were found in QOL functional domains especially roll function and social function but difference to baseline did not reach significance (Fig 5 & 6).

0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 Physical functioning Role functioning Emotional functioning Cognitive functioning Social functioning Global health M ea n Sc or e 0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 Physical functioning Role functioning Emotional functioning Cognitive functioning Social functioning Global health M ean S cor e baseline Follow-up A. Exercise group B. Control group

*

Fig 5. Comparison changes of mean functional scores of exercise group compared with control group in EORTC QLQ C-30. A higher score represents a higher level of

functioning or global health status/QOL *Differences in health-related quality of life scores between groups were considered clinically relevant if 10 points

0 10 20 30 40 50 Lymphedema Peripheral neuropathy Menopausal symptoms

Body Image Sexual worry Sexual activity Sexual/vaginal functioning Sexual enjoyment 0 10 20 30 40 50 60 Lymphedema Peripheral neuropathy Menopausal symptoms

Body Image Sexual worry Sexual activity Sexual/vaginal functioning Sexual enjoyment baseline Follow-up A. Exercise group B. Control group * * *

Fig 6. Comparison changes of mean functional and symptom scores of exercise group compared with control group in EORTC QLQ CX-24. A higher score represents a higher

level of functioning or global health status/QOL (A and B) and higher symptom score represents a higher perception of the symptom (C and D) *Differences in health-related quality of life scores between groups were considered clinically relevant if 10 points

Ⅳ. DISCUSSION

This research examined the pelvic floor dysfunction and QoL issues in gynecological cancer survivors. The results of this study demonstrate that women with treatment of gynecological cancer have more pelvic floor dysfunction compared to the reference group. Nocturia and urinary incontinence in bladder function and straining, urgency and incomplete emptying stool in bowel function are most pronounced and have a relevant impact on HRQOL especially physical functioning. Patients receiving pelvic floor rehabilitation program have higher their pelvic muscle strength, better pelvic floor function and more enhanced excitatory motor pathway compared to the control group. After exercise, participants reported less sexual worry and better physical functioning and sexual activities

In our study, stress incontinence and nocturia were significantly higher in gynecological cancer survivors. Urinary incontinence, chiefly, stress incontinence, is a common problem after radical hysterectomy and it‟s reported in 19-81% of patients with gynecological cancers.(Jackson and Naik 2006) The etiology of genuine stress incontinence after radical surgery is uncertain, but it may be the result of disruption to the anatomic support of the bladder and urethrovesical junction following resection of the upper vagina and parametrium or related to pudendal and pelvic nerve damage and loss of periurethral tone.(Jackson and Naik 2006). In a cross-sectional matched cohort study(Hazewinkel, Sprangers et al.), the gynecological cancer survivors had a

significantly higher risk of stress incontinence than the reference group. According to Hsu et al., (Hsu, Chung et al. 2009) pelvic neural dysfunction was higher in surgery patients. They suggested that the direct injury of traction during surgery{Carlson, 1997 #319}, pelvic anatomic dislocation after surgical manipulation{Lin, 1998 #322}, and excision of tissues around vagina (Ercoli, Delmas et al. 2003; Raspagliesi, Ditto et al. 2007) may have caused damage on pelvic nerves (especially on bladder and urethra) during radical hysterectomy. Brooks and co-workers (Brooks et al.2009) recently reported that urinary incontinence is common late side effects after radical hysterectomy. They detected bothersome urge and stress incontinence in, respectively, 17% and 27% of 66 patients treated with radical hysterectomy. In that respect, the 47.5% of our patients with urinary incontinence is more prevalent than the proportions mentioned by Brooks et al.

We found incontinence group patients had weaker pelvic floor muscle strength and impaired pudendal nerve. Revealing neurogenicity in a patient with pelvic floor dysfunction may alter the choice of therapy. It is known that pudendal nerve innervates the levator ani muscles which have key role of continence. Continence and coordinated micturition, as well as defecation, sexual arousal, and orgasm, are dependent on the integrity of the central and peripheral nervous pathways to the sacral region. Nerve damage is more frequent in incontinence patients than in continent controls. In our pilot study, one participant in the intervention group showed delayed onset of latency produced with sacral stimulation (6.0msec) in left side. She had leg lymphedema left side

and urinary symptom such as urinary urgency. Our study comprised only very few participants, so the further study is needed to replicate our findings.

We could appraise the excitability of the intracortical motor circuitry corresponding to the anal sphincter. With muscle contraction, the latencies of motor evoked potential were reduced and amplitudes were increased. In one case, the potential which was not recorded to the cortical stimulation at rest was evoked after facilitation. The latency to the cortical stimulation with facilitation in the incontinence group was larger than that in the continence group. In the incontinence group with intact sacral function, they may contract the pelvic floor muscle less than 10% of maximal contraction at baseline. There is a correlation between the increase in voluntary contraction of the target muscle and the reduction in latency, until a certain level of around 10-15% of maximal contraction (Ravnborg, 1996). However, pelvic floor contraction is difficult to verify and quantify, and the ability to voluntarily contract the pelvic floor is not present in many women (Bump et al., 1991). That is the one of the reason in the development of PFRP to improve the pelvic floor function in gynecological cancer survivors.

Transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) is one potential approach in the assessment of the corticospinal pathways and sacral plexus function. Gunnarsson et al. studied 18 women with genuine stress urinary incontinence are found that the women who responded well to pelvic floor exercises also produced shorter latencies to cortical stimulation with facilitation. Even though the role played by the motor cortex in anorectal pathophysiology is not completely understood (Vodusek 2004), Lefaucheur

(Lefaucher 2005) assessed the excitability of the external anal sphincter with the rest motor threshold and the duration of the cortical silent period with single TMS pulses. In our study, participants received PFRP showed increased amplitude and decreased the motor threshold of pudendal nerve stimulating cortical area with facilitation. These finding could be interpreted as the enhanced excitability of the motor cortical representing the external anal sphincter.

Bowel function was impaired especially in straining and urgency for defecation. Hazewinkel et al (Hazewinkel et al., 2010) also reported that the prevalence of urgency for defecation and distress from constipation and obstructive defecation was significantly more after radical hysterectomy than in the reference group. Hsu et al. reported that radiotherapy patients exhibited greater intestinal dysfunction (Hsu et al.2009). Many studies have indicated that radiotherapy to the pelvic cavity has easily caused diarrhea and abdominal pain (Haboubi et al 1988; Classen et al., 1998;Danielsson et al.,1991; Lantz et al., 1984). Pieterse et al. did not find increased prevalence bowel symptoms at 24 months after treatment of early-stage cervical cancer (Pieterse et al.,2006). However, they used a non-validated questionnaire with only two questions about bowel function.

Sexual inactivity has been reported in almost two of third patients in gynecological cancer survivors. Sexual dysfunction in this study is mainly caused by dyspareunia and viginal dryness. It is known that sexual dysfunction from surgery is caused by a shortened vagina (Jensen et al., 2004), vaginal dryness (Jensen et al. 2004; Schover et al. 1989; Bukovic et al.2003; Burns et al.,2007), and decreased libido (Herzog et al.,2007;

Bukovic et al.2003;Jensen et al., 2003; Seibel et al., 1982; Cull et al., 1993). In contrast, the sexual dysfunction from radiotherapy are caused by vaginal stenosis which yields dyspareunia, difficulty in orgasm, decrease in sexual satisfaction, and change in body image. A cross-sectional study of 860 survivors of cervical cancer found that survivors of cancer also experienced worse body image, impaired sexual/vaginal function, and more sexual worry when compared with 494 control subjects with no history of cancer (Wenzel et al.,2005).

In addition, there was a strong association between pelvic floor dysfunction and several HRQOL aspects. “Physical functioning” is the most severely impaired functioning as expected, and the present study confirms that “social functioning” is also important limitation in these patients. Interestingly, as compared to reference group, clinically meaningful worse outcomes were found for constipation and diarrhea, indicating that these aspects are greatly impaired after the treatment in gynecological cancer survivors.

PFRP has been found especially valuable in case of stress incontinence, which is a major component of pelvic floor dysfunction in gynecological cancer survivors. Moreover, they have a beneficial effect on HRQOL measurements. In our study, significantly greater post-exercise changes in the scale of peak vaginal pressure. The prevalence of stress incontinence was decreased from 64.3% to 33.3% after the intervention in the exercise group. Burgio et al (Burgio et al., 1998 Behavioral vs drug treatment for urge urinary incontinence in older women) reported a mean 80.7%

reduction in incontinence episodes in women with incontinence using anorectal biofeedback to help train their pelvic muscles.

The mechanism behind this effect is not yet defined but with the results of our study, we suggested several hypotheses. We assessed the excitability of the motor cortical representation of the external anal sphincter by using transmagnetic stimulation (TMS). After exercise, the latency to the cortical stimulation with facilitation was significantly shorter than that at baseline in exercise group. In both group, the latencies after muscle contraction became shorter, however the comparison of difference of latency showed significance between the groups. To achieve minimal latency of MEPs, a contraction more than 10% of maximal voluntary contraction (MVC) is needed. It is difficult to contract pelvic floor muscle maximally, but after PFRP, a degree of voluntary activation increased. It has been reported that the facilitative role of central nervous system was dependent on a degree of voluntary activation (Hanptmann et al., 1996; Mill and Kimiskidis,1996).

We found that exercise group reported significantly higher QoL than that of control group. Moreover, the differences in QoL scores meet the previously identified minimally important differences on the EORTC QLQ C-30 and CX-24. In follow-up analysis of subscales, physical functioning were most strongly associated with exercise group. We found that physical functional aspect of QoL was significantly improved in the exercise group. Physical function are important in activities of daily living for cancer survivors and have been shown to be the most important but also the most compromised aspect of

QoL for gynecological cancer survivors. Many researches in other groups of cancer survivors also has demonstrated that exercise interventions can increase muscular strength and endurance, physical functioning, and cardiovascular fitness. These results indicate that exercise is an important and effective intervention for improving and maintaining physical functional aspect of QoL in gynecological cancer survivors. In addition, we developed cancer specific exercise program.

This study has several limitations. The cross-sectional evaluation of pelvic floor dysfunction in gynecological cancer survivors did not allow us to adjust the analysis for baseline data before treatment. In addition, the inclusion criteria and the sample size of the study might have reduced the generalisability of the study and limited the power of the analysis, respectively. A further limitation of the study is related to the characteristics of the reference group. Because of the lack of Korean normative data for the EORTC QLQ-C30 and CX-24, this study used age-matched reference group this not fully taking into account the characteristics of general population.

The duration of the exercise program (4 weeks) was unlikely to be long enough to verify the effects of exercise. Our program may not be of sufficient intensity to change in a short period. More extended duration and frequency of the intervention, longer-term follow-up, and larger sample size are needed to evaluate the effectiveness of PFRP in the gynecologic cancer survivors.

Despite these limitations, our results provide a preliminary indication that a pelvic floor rehabilitation program may be efficacious with regard to urinary incontinence and

quality of life. Considering the effect sizes for the rate of urinary incontinence between groups, the sample size required at 5% significance level and 80% power was 250 survivors of gynecological cancer per group.

Ⅴ. CONCLUSIONS

The gynecological cancer survivors had pelvic floor dysfunction that affected their quality of life.In this small, short-term pilot study, PFMT integrated with core exercise may improve quality of life of gynecological cancer survivors with pelvic floor dysfunction through increased pelvic muscle strength and enhancing excitatory motor pathway. Larger randomized, long-term trials are needed to determine the effectiveness of the proposed therapeutic approach.

Supplier

REFERENCES

Aaronson, N. K., S. Ahmedzai : "The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C30: a quality-of-life instrument for use in international clinical trials in oncology. J Natl Cancer Inst 85: 365-376, 1993

Amuzu, B. J. : Nonsurgical therapies for urinary incontinence. Clin Obstet Gynecol 41: 702-711, 1998

Baessler, K., S. M. O'Neill : Australian pelvic floor questionnaire: a validated interviewer-administered pelvic floor questionnaire for routine clinic and research. Int

Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct 20: 149-158, 2009

Barker, C. L., J. A. Routledge: The impact of radiotherapy late effects on quality of life in gynaecological cancer patients. Br J Cancer 100: 1558-1565, 2009

Benedetti-Panici, P., M. A. Zullo : Long-term bladder function in patients with locally advanced cervical carcinoma treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy and type 3-4 radical hysterectomy. Cancer 100: 2110-2117, 2004

Blazeby, J. M., K. Avery : Health-related quality of life measurement in randomized clinical trials in surgical oncology. J Clin Oncol 24: 3178-3186, 2006

Blomberg, S., K. Svardsudd : A controlled, multicentre trial of manual therapy in low-back pain. Initial status, sick-leave and pain score during follow-up. Scand J Prim Health

Care 10: 170-178, 1992

Bo, K., T. Talseth : Randomized controlled trial on the effect of pelvic floor muscle training on quality of life and sexual problems in genuine stress incontinent women. Acta