저작자표시-비영리-변경금지 2.0 대한민국 이용자는 아래의 조건을 따르는 경우에 한하여 자유롭게

l 이 저작물을 복제, 배포, 전송, 전시, 공연 및 방송할 수 있습니다. 다음과 같은 조건을 따라야 합니다:

l 귀하는, 이 저작물의 재이용이나 배포의 경우, 이 저작물에 적용된 이용허락조건 을 명확하게 나타내어야 합니다.

l 저작권자로부터 별도의 허가를 받으면 이러한 조건들은 적용되지 않습니다.

저작권법에 따른 이용자의 권리는 위의 내용에 의하여 영향을 받지 않습니다. 이것은 이용허락규약(Legal Code)을 이해하기 쉽게 요약한 것입니다.

Disclaimer

저작자표시. 귀하는 원저작자를 표시하여야 합니다.

비영리. 귀하는 이 저작물을 영리 목적으로 이용할 수 없습니다.

변경금지. 귀하는 이 저작물을 개작, 변형 또는 가공할 수 없습니다.

사회복지학석사학위논문

A study of Child Neglect, Social- Emotional Development, and School Relationships Among Left

Behind Children in Rural China

중국농촌 유수아동의 아동방임과 사회정서적 발달 및 학교내에서의 관계 연구

2018년 8월

서울대학교 대학원 사회복지학과

장옥미

A study of Child Neglect, Social- Emotional Development, and School Relationships Among Left

Behind Children in Rural China

ZHANG YUMEI

A DISSERTATION

SUBMITTED TO THE DEPARTMENT OF SOCIAL WELFARE AND THE COMMITTEE ON THE GRADUATE SCHOOL IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS

FOR THE DEGREE OF

MASTER OF ARTS IN SOCIAL WELFARE

SEOUL NATIONAL UNIVERSITY

MAY 2018

i

Abstract

A study of Child Neglect, Social-Emotional Development, and

School Relationships Among Left Behind Children in Rural China

ZHANG YUMEI Department of Social Welfare The Graduate School Seoul National University

The purpose of this study is to understand the status of neglect of children in China's rural areas, especially left-behind children, and the relationship with social-emotional development. With the background of the school environment in which most children live, this study assumes that peer relationship and teacher-student relationship in the school can serve as a protective moderating factor that child neglect impact on the social-emotional development. Explore whether peer relationships and teacher-student relationships play a moderating role in the relationship between child neglect and social-emotional development. This will provide a scientific basis for systematically constructing a theoretical and practical system for preventing rural neglected children from neglecting and improving social-emotional development.

This study used a Chinese children's neglect scale developed by

ii

Chinese scholars (e.g. physical neglect, emotional neglect, medical neglect, education neglect, and safety neglect), and the social- emotional development scale (e.g. self-esteem, resistance and life satisfaction), and in-school relations scale (e.g. peer relationship, teacher-student relationship) in the survey on "Korea Child and Youth Panel Survey 2010" . A total of 550 children from grade 4 to grade 8 in seven schools in rural Juye County, Shandong Province were surveyed. A total of 479 valid questionnaires were retrieved, including 113 non-left-behind children. After excluding the missing values of the relevant control variables, 293 left-behind children were analyzed.

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS version 20.0 statistical software and t-test and linear regression analysis were used when analyzing differences in the level of child neglect. When analyzing the overall level of child neglect, sub-scales of child neglect and social emotional development, and verifying moderating effects of peer relationship and teacher-student relationship, hierarchical regression analysis was used separately.

The result shows, firstly, there was no significant difference in the level of neglect among left-behind and non-left-behind children.

However, when the type of children was based on the non-left-behind children, only one parent migrated to work and parents both migrated to work as dummy variables and found that there is a significant difference in the level of neglect between non-left-behind children and children their parents both migrated. Secondly, after controlling relevant variables, the level of neglect of all children and left-behind children both have significant effect on social-emotional development. However, from the perspective of sub-scales of child neglect, of which five neglect types, only emotional neglect has a significant effect on social-emotional development.Thirdly, for left-behind children, peer

iii

relationship has a significant moderating effect in the relationship between child neglect and social-emotional development, however, the moderating effect of teacher-student relationship on the relationship between child neglect and social-emotional development was not statistically significant. Moreover, whether peer realationship or teacher-student relationship as a moderator factor, in the relationship between sub-scales of child neglect and social-emotional development, no statistically significance has been found.

The limitations of this study include the following points. Firstly, this study only selected children in a rural area of Shandong Province, China. It could not represent the situation of left-behind children in China. The age range was from grade 4 to grade 8 and did not include younger children. Secondly, the reliability of self-esteem in social-emotional development was low, which may be related to the characteristics of children in this age group. Thirdly, this study used cross-sectional surveys for analysis. Further studies utilizing panel data and longitudinal data for analysis on the time-based interaction will be required.

Keyword : Left behind children, Child neglect, Social-emotional development, Peer relationship, Teacher-student relationship, Rural China

Student Number : 2016-22069

iv

CONTENTS

Chapter 1. INTRODUCTION... 1

1.1. Study Background...

11.2. Significance of Research...

21.3. Purposes of Research...

51.4. Research Questions...

6 Chapter 2. LITERATURE REVIEW...72.1. Child Neglect...

72.1.1 Defining Child Neglect...

72.1.2 Literature Review on Child Neglect...

112.2. The Relationship Between Child Neglect and Social-Emotional Development...

142.2.1 Defining Social-Emotional Development...

142.2.2 Literature Review of the Relationship Between Child Neglect and Social-Emotional Development...

162.3. The Moderating Effect of School Relationships on the

Correlation Between Child Neglect and Social-Emotional

Development...

172.3.1 Defining School Relationships...

172.3.2 Attachment Theory...

182.3.3 Effects of Peer and -Student Relationships on Social-

Emotional Development...

202.3.4 The Moderating Effect of School Relationships on the

Correlation Between Child Neglect and Social-Emotional

Development...

212.4. Summary and Analysis of Research Status...

23 Chapter 3. CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK AND RESEARCHHYPOTHESES...25

3.1. Conceptual Framework...

253.2. Research Hypotheses...

27 Chapter 4. RESEARCH METHOD...29v

4.1. Research Procedures and Sampling...

294.1.1 Research Design...

294.1.2 Participants...

304.1.3 Data Collection...

314.1.4 Research Procedures...

324.2. Measurement of the Variables...

334.2.1 Dependent Variable: Social-Emotional Development...

334.2.2 Independent Variable: Child Neglect...

344.2.3 Moderating Variables...

364.2.4 Control Variables...

374.3. Analytic Technique and Diagnostics...

40 Chapter 5. RESEARCH FINDINGS...425.1. Socio-Demographic Characteristics...

425.2. Descriptive Statistics of the Major Variables...

485.3. Correlation Matrix of Major Variables...

505.4. Test of Hypotheses...

535.4.1 Correlation Between LBC Status and Child Neglect...

535.4.2 Relationship Between Child Neglect and Social

-Emotional Development...

565.4.3 The Hierarchical Analysis of the Moderating Effect of Peer and Teacher-Student Relationships on Social-Emotional

Development of LBCs (Model 3)...

645.4.3.1 Analysis of the Moderating Effects of Peer and

Teacher-Student Relationships on the Correlation Between Child Neglect and Social-Emotional Development

(Model 3-1)...

655.4.3.2 Analysis of the Moderating Effects of Peer and

Teacher-Student Relationships on the Correlation Between the Five Sub-Scales of Child Neglect and Social-Emotional

Development (Model 3-2)...

68 Chapter 6. CONCLUSION...726.1. Summary of Findings...

726.2. Discussion...

76vi

6.2.1 What influences the difference in neglect level between

LBC and non-LBC?...

766.2.2 The relationship between child neglect and social

-emotional development among LBCs...

786.2.3 Peer and student-teacher relationships as moderating

variables on social-emotional development among neglected

LBC...

796.3. Research Implications...

806.3.1 Theoretical Implications...

806.3.2 Practice and Policy implications...

826.4. Limitations of the Study, and Suggestions for Future

Study...

84REFERENCES...88 APPENDIX...101 국문초록...127

vii

TABLES

[Table 4-2-1] Reliability of the Social-Emotional Development

Scales ... 34 [Table 4-2-2] Reliability of Chinese Version of Child Neglect in

Rural Areas Inventory...35 [Table 4-2-3] Reliability of Moderating Variables...37 [Table 4-2] Major Variables in the Present Study...38 [Table 5-1] Respondents’ Socio-Demographic Characteristics

(all children)...43 [Table 5-1-1] Respondents’ Socio-Demographic Characteristics

(for LBCs)...46 [Table 5-2A] Descriptive Statistics of Major Variables

(for all children)... 49 [Table 5-2B] Descriptive Statistics of Major Variables

(for LBCs)...50 [Table 5-3A] Correlation Coefficients for All Children...51 [Table 5-3B] Correlation Coefficients for LBCs... 52 [Table 5-4-1A] Difference in Child Neglect Level Between LBC

and non-LBC Groups...53 [Table 5-4-1B] Hierarchical Regression for Child Neglect Level

for All Children...55 [Table 5-4-2A] Hierarchical Regression on Social Emotional

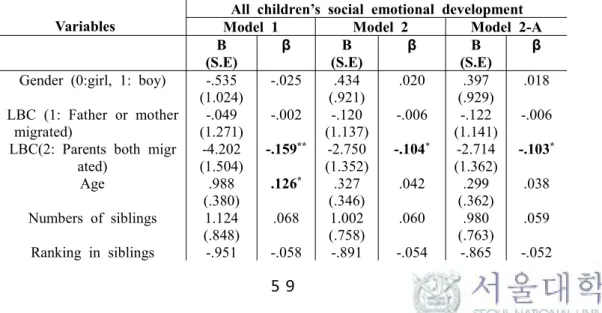

Development for All Children... 59 [Table 5-4-2B] Hierarchical Regression on Social Emotional

Development for LBCs...62 [Table 5-4-3A] Hierarchical Multiple Regression Analyzing

Moderating Effects of Peer and Teacher-Student Relationships on the Negative Correlation Between Child Neglect and Social

-Emotional Development for LBCs...67

viii

[Table 5-4-3B] Hierarchical Multiple Regression Analyzing Moderating Effects of Peer and Teacher-student Relationships on the Correlation Between sub-scales of Child Neglect

and Social-Emotional Development for LBCs... 70 [Table 6-1] Summary of hypotheses and results...75

FIGURES

[Figure 3-1] Conceptual Framework of the Present Study... 26

[Figure 5-1] Equations for Models 1, 2, and 2-A... 57

11

Chapter 1. INTRODUCTION

1.1. Study Background

Since the mid-1980s, China has witnessed what some scholars describe as the largest peacetime population movement in world history (Roberts, 2002). Citizens from rural areas have rapidly migrated to urban areas due to better salaries and employment rates. Some migrant families bring their children to the city while others do not;

thus, two vulnerable groups of children have been created. The first are migrant children living on the edge of the city with their migrant parents, also known as floating population children. The second are left-behind children (LBCs) remaining in rural areas without their parents. This occurs because, under the household registration system, families can only receive social welfare in their hometown. Living in the city under great pressure, but within their wages, is difficult.

Therefore, parents are forced to leave their children in rural areas so that they can receive free education and other social welfare. As a result, the LBC population has risen in rural China.

LBC refers to a child who stays at home when one or both of his or her parents relocates elsewhere to work for at least six months (Duan & Zhou, 2005). It is estimated that about 120–150 million migrant workers have moved to major cities in China from the 1980s to 2000s (Pan, 2002), and the number of migrant workers has continued increasing. The All-China Women’s Federation (2014) issued a report entitled "Situation of children left behind in rural China Research Report in 2014." This report, using data from China’s 2010 census, estimated that the country’s rural LBC count was 61.02 million children, accounting for 37.7% of rural children and 21.88% of the the

21

entire country’s youth population (All-China Women's Federation, 2014).

The LBC population has also become a concern for the government, media, and social organizations. The “Outline of China's National Medium- and Long-Term Education Reform and Development Plan (People’s Republic of China, 2010 – 2020)” clearly stated the need for “the establishment of a care service system and dynamic monitoring system for rural left-behind children.” In 2016, the State Council of the People's Republic of China issued a report “About Strengthening Rural Left-behind Children caring for Protection Work”

(Xue & Jia, 2015). Obviously, this topic is of great importance and there is a need to explore the neglect of rural LBCs and their social- emotional development (SED).

1.2. Significance of Research

The development of children and adolescents is interactively influenced by multiple environments, including the family, community, and society. In other words, adolescent development is a product of both environmental and social impacts (Jeong, 2010). A previous study showed that school is a place where children and adolescents can spend more than 15,000 hours during their development. Therefore, it is an especially important environment for their maturation (Ruter &

Maughan, 2002 cited, Kurien, et, al., 2002).

With the development of self-awareness, LBCs shift from dependence on parents to independence from parents; when this happens, peer and teacher-student relationships have an even more important impact on their lives. Also, the field of child and adolescent development can be divided into physical, cognitive, and social- emotional development, and each area influences the others. Youth

31

are constantly adapting to school life, changes in their roles, and changes in the environment, which are all types of psychological adaptation. Therefore, instead of focusing on physical or cognitive development, this study addresses social-emotional development by examining LBCs in the school environment.

When parents are absent, school is the place where LBCs spend most of their time and establish their main relationships. Therefore, it is particularly important to explore their social-emotional adaptation and development in this environment because of its impact on their growth.

Studies of child neglect worldwide have shown that neglect not only affects the survival, safety, and physical development of children, but also their personalities and social growth (Gil, 1969; Sedlak, 2001).

Over the past decade, the issue of social-emotional development has become an important topic in psychology, especially in psychological research. The current research on social-emotional development has become more concerned with the problems encountered in real-life situations. The research on these problems can help solve the practical issues that developing children face.

Therefore, researchers not only pay attention to children's social- emotional development, but also to the development process, that is, how children solve these problems. It is possible to effectively intervene in such issues after identifying which specific patterns of growth will improve children’s habits so that they can achieve adequate social maturation (Nian, 2010).

Familial neglect is an important issue in the study of child development. In-depth research on this issue will contribute to the development of interventions and preventative measures. This will ultimately reduce the range of problems that arise from the inadequate socialization of children to help them achieve better social-emotional

41

development. Social-emotional development is part of the psychosocial domain, which includes changes in attachment, emotions, personality, identity, and interpersonal relationships (Seifert & Hoffnung, 2000; Lee, 2007 cited). Neglect is a risk factor in early childhood development that affects children's psychosocial domain.

Several studies have shown that 12 to 17-year-old middle school students are neglected at an alarming degree in rural China (Nian, 2010; Gu, 2012; Liu, 2012; Wang, 2011). Child neglect is a widespread phenomenon in China, especially in the economic, cultural, educational, and social development of rural areas. In these areas, there is a higher frequency and extent of neglect, especially for LBCs and children with only a single parent.

Neglect may be more serious for LBCs, affecting their personality and socialization skills. Most previous studies focused on the factors that children being neglected (Gu, 2012; Liu, 2012) and the effects on loneliness, self-esteem (Han, 2012), cognition, and peer relationships (Sun, 2005; Sun, 2006; Chang & Wang, 2008; Nian, 2009; 2010).

However, there has not been any research on the moderating effects of school relationships on the social-emotional development of neglected children. Therefore, the present study suggests that peer and teacher-student relationships can be a protective factor for neglected children who have been separated from their parents for a long period of time. These relationships play a compensatory role.

Consequently, this study is necessary because it focuses on child neglect and social-emotional development using peer and teacher- student relationships as a moderating variable. In addition, the empirical evidence has important theoretical and practical significance on the necessity of intervention for LBCs and the need to take action to end child neglect in rural China.

51

1.3. Purposes of Research

LBCs have become an important issue in Chinese society, but there has so far been little attention paid to child abuse and neglect.

Child neglect due to being left behind is a result of the political environment. The household registration system and urban-rural population movements are both policy and social issues. These issues originated in the 1980s and have continued into the present day, and an adequate solution has not been found. However, child neglect must be solved quickly; it cannot wait.

Therefore, the solution must begin with the practice of intervention by encouraging social organizations and providing social services as compensation for LBCs’ psychological or material deficiency . From the perspective of social welfare, this study focuses on the school environment and explores the relationship between child neglect, relationships in school, and social-emotional development.

In summary, the current study compares three different groups of children in rural communities in Shandong province of China: non-LBC, LBC1 (only father or mother migrated) and LBC 2 (both of their parents migrated). The purpose of this study is to examine the similarities and differences in levels of neglect among these children.

The relationship between child neglect and social-emotional development is explored for all children as a whole as well as the LBC group specifically.

Three social-emotional development sub-scales were addressed in this study: self-esteem, resilience, and life satisfaction, and SED was measured by the total score. It was hypothesized that peer and teacher-student relationships would improve the social-emotional

61

development of neglected children (Zhao, Liu & Wang, 2015). This is because high levels of peer and teacher-student relationships would weaken the negative outcomes of neglect, especially for children with two migrant parents(Jin et al., 2015).

1.4. Research Questions

The current study, conducted with children, teachers, and parents in mainland China, focuses on the correlation between social-emotional development and interpersonal relationships for LBCs. It raises the following research questions:

Research Question 1: Is the level of child neglect higher for LBCs than non-LBCs?

Research Question 1-1: Is child neglect level of LBCs higher than that of non-LBCs?

Research Question 1-2: What’s the difference of child neglect level among different LBC categories?

Research Question 2: What is the relationship between child neglect, its sub-scales, and social-emotional development?

Research Question 3: Do peer and teacher-student relationships moderate the negative effects of different types of neglect on social- emotional development among LBCs?

Research Question 3-1: Do peer and teacher-student relationships moderate the negative effects of child neglect on social-emotional development?

Research Question 3-2: Do peer and teacher-student relationships moderate the negative effects of sub-scales of child neglect on social- emotional development?

71

Chapter 2. LITERATURE REVIEW

2.1. Child Neglect

2.1.1 Defining Child Neglect

Henry et al. (1962) addressed the issue of child abuse in the American Journal of Medicine for the first time and raised the issue of child abuse syndrome, which became a growing international concern.

In 1977, the World Health Organization (WHO) proposed the concept of child neglect and noted that child abuse and neglect were a social phenomenon and public health problem that had existed in all societies throughout history. In the same year, the International Association for the Prevention of Child Abuse and Neglect (ISPCAN) was established and an international conference was held every two years since. Since then, many countries have established specialized organizations and institutions dealing with and intervening in child abuse and neglect.

In the 1980s, more developing countries began to pay attention to this issue. Europe, the United States, Japan, South Korea, Taiwan, and others have ignored the inclusion of child welfare issues managed by the social welfare sector. At the same time, the Child Welfare Law was enacted to address the problem of child neglect at the institutional and legal levels.

There is no worldwide, uniform definition of child neglect. This is due to the differences in economic, cultural, traditional, and lifestyle customs of each country, which result in different understandings of neglect. There is also a close relationship between neglect and

81

poverty. At present, the definition of child neglect, proposed by the MH Golden Honorary Professor of the University of Aberdeen in 2002, is "negligence and failure to meet the needs of children, so that harm or damage occur to the health or development of children." (Yang et al., 2004).

Gibbons (1994) argued that neglect is long-term, sustained, or serious treatment that results in a child not receiving adequate protection from danger, the elements, or hunger. It also includes not providing important care for the child, resulting in health or developmental issues or severe injury. It is generally accepted that there are four types of neglect: physical, emotional, medical, and educational (Sun et al., 2006). Some scholars believe that the definition of neglect should be expanded to include safety, social, and nutritional neglect as well as a lack of proper clothing or quality training for parenting (Duan et al., 2006).

In this research, child neglect refers to when a child's caregiver does not provide adequate care for satisfying the basic needs of the child due to serious or prolonged negligence, so as to endanger or impair the health, safety, or development of the child (Pan et al., 2011). This paper includes five types of neglect: physical, emotional, medical, educational, and safety(Pan, 2007).

2.1.1.1 Types of Child Neglect

(1) Physical neglect refers to the improper care of the child's body;

it can also occur before the child is born.

(2) Emotional neglect refers to the lack of love for the child, not providing adequate psychological, spiritual, and emotional care and communication, and not meeting the emotional needs of the child.

(3) Medical neglect refers to an absence or delay in meeting the

91 child’s medical and health care needs.

(4) Education neglect means not providing access to educational opportunities, thus reducing the child's intellectual development and acquisition of knowledge and skills.

(5) Safety neglect refers to ignoring the child's growth, living environment, and the existence of security risks, so that the child’s health or life may be in danger.

2.1.1.2 Evaluating Child Neglect

Two major approaches are generally followed when determining the prevalence of child maltreatment and neglect. First, child abuse and neglect is estimated using information from mandated reporters, such as pediatricians, preschool teachers, and child protective services workers. For example, the National Child Abuse and Neglect Data System (NCANDS) releases national incidence studies (NIS) on child abuse and neglect in the U.S. using sentinel survey methodology (Sedlak et al., 2008). This methodology uses reports from mandated reporters as defined by Child Protective Service (CPS). Specifically, mandated reporters have close contact with children and their families, and they provide information about suspected child maltreatment cases to CPS. Agencies, both sentinel and CPS, are selected for study using a stratified sampling strategy. Other countries, such as Canada and the Netherlands, have also used this approach to estimate prevalence rates of child maltreatment (Euser et al., 2010; Trocme et al., 2001; 2010 recited).

The second approach for estimating child maltreatment rates is using self-reports from caregivers and children. For example, the United States, United Kingdom, and Korea have relied on self-reports

101

by caregivers and children (Hong et al., 2000; Lee et al., 2009).

Due to the differences in social, cultural, economic, religious, and societal custom, child neglect evaluation methods and standards have not yet been developed at a unified international level. In general, countries determine child neglect based on their own national guidelines for the development of children. In China, the first survey of child neglected was done by Pan Jianping (2002) and took data from 25 cities in 14 provinces. This survey used the "3–6 Year Old Urban Children Neglect Investigation Cooperation Group" to evaluate the degree of physical, emotional, educational, and medical neglect of Chinese preschool children (Pan et al., 2003). In addition, there was an evaluation for urban 7 to 18-year-old students and rural 0 to 18- year-old children.

Pan et al. (2014) created the “Development of neglect evaluation norms for 12–17 middle school students in rural areas of China,” which used multi-stage stratified cluster sampling to investigate 12 to 17-year-old middle school students. The total population studied was 6196, with an equal number of males and females, and minorities accounted for approximately 6.4% of the population. Data were collected by questionnaires completed by students. The neglect questionnaires contained 6 levels of neglect with a total of 72 items.

The researches performed project, factor, reliability, and validity analyses on the data, deleting items which did not reach statistical requirements (p > .05). They then created the formal scales, thus completing the initial development of forms of neglect.

111

2.1.2 Literature Review on Child Neglect

In recent years, domestic and foreign experts and scholars from a variety of disciplines and perspectives have performed research on rural child neglect. In this section, a brief overview of child neglect research is included.

In 1994, the National Committee to Prevent Child Abuse survey showed that 49% of injuries were caused by neglect since 1986.

According to this, it was estimated that child abuse and neglect in the United States in the previous 10 years had increased by 63%

(Matthew et al., 2004). Julie et al. (2001) pointed out that "in American society, children' The form of expression is the neglect of children, but today the problem of neglect of children has not yet attracted attention. Kathryn et al. (2002) noted that "children are neglected as the most common form of children's 'injury' affecting children's development."

Compared to other countries, research by Chinese experts and scholars on LBC neglect started late. In the 1980s, China began to pay attention to child neglect and take the appropriate countermeasures. In 1999, China held the first "Seminar on Prevention of Child Abuse and Ignorance" in Shaanxi Province, and established the Shaanxi Provincial Committee for the Prevention of Child Abuse and Neglect(Wang, 2011). This was the first relevant organization in China dedicated to child neglect.

In 2001 to 2002, Pan Jianping used "China 3- to 6-year-old urban child neglect norm" and found that the urban rate of neglect for children ages 3–6 years was 28.0% (Ye, Yao, & Dong, 2004; Yang, 2003). Pan et al. (2014) founded that the total neglect rate① was

① Neglect rate based on whether the cut-off score is exceeded to determine

121

47.3% and the total degree was 49.40±9.48 for middle school students ages 12–17 years in rural China. Liu Chenyu (2012) found that the total neglect rate and degree for children ages 0–6 years were 31.59% and 48.32, respectively.

In western China (Chongqing province & Shaanxi province), the total rate of neglect of male and female children was found to be 32.63% and 30.38%, respectively. The total neglect rate was 48.56 and 48.05, respectively. The total rate and degree of neglect were lower for families with three generations or core families than for single-parent families and families in which the parent(s) had remarried.

The total rate and degree of neglect were higher for LBCs than for non-LBCs.

The Liu(2012)’s results from an urban school survey of 6 to 17- year-olds showed that the neglect rate and degree for urban primary and middle school students were 30.30% and 45.27 ± 8.71, respectively. The neglect rate was higher for boys than for girls.

Middle school students (12 to 17-year-olds) had the highest degree of neglect. Single-parent families and families in which parents had remarried had lower rates of neglect than families with three generations or core families. Neglect rate and degree were higher in families with more than one child than in families with only one child.

In Gu (2012)’s survey, the prevalence of child neglect among students was 67.4%, and the prevalence of child neglect among LBCs (70.2%) was higher than that among other children (63.5%). The researcher also found that neglect was more likely for children who

whether the child is neglected, the number of neglected children divided by th e total number of children surveyed is their rate of child neglect. Degree of n eglect means the level of child neglect, The higher the score, the more serio us the degree of neglect, the lower the score, the better (Pan et al., 2001).

131

were left behind, at boarding school, from dysfunctional families, or had a low quality of life.

Wang (2011) conducted a survey on the guardians of children ages 8–11 from schools in rural areas of Hebei, Hunan, Jiangsu, Sichuan, and Anhui. The overall neglect rate was 51.18% and the neglect degree was 52.78±4.007. The rate and degree of neglect were higher for girls than boys. Also, the rate and degree of neglect declined with age for LBCs. LBCs had the highest rate and degree of educational neglect, followed by emotional neglect. Girls were less likely to experience physical neglect, and boys were more likely to experience medical care neglect.

In many studies (Yang & Zhang, 2002; Pan et al., 2003; 2005;

Zou et al., 2010; Chen & Wang, 2003; Huang et al., 2006), child abuse and neglect have been shown to lead to physical or mental impairments; cognitive, emotional, physical, and developmental disorders; physical and mental damage; and even death.

Foreign scholars have mainly focused on the physical, psychological, and behavioral aspects in studies on neglect. Hildyard et al. (2002) pointed out that both past and current studies have shown that children were neglected, social-emotional and behavioral effects of children, who develop short- or long-term adverse effects, especially in the early stages of life. However, serious harm can also occur to the child's future development. The negative effects of neglect can extend into adulthood, leading to adverse social or emotional reactions and resulting in physical, psychological, and behavioral disorders. Widom &

Du Mont (2007)’s study showed that child abuse and neglect could lead to emotional or mental disorders in adulthood and are closely related to the occurrence of personality disorders. Huebner et al.

(2000) believed that childhood neglect is a main risk factor for a

141

variety of psychological problems or mental disorders because the child’s growth took a major psychological blow.

Many studies have shown that the adverse effects of neglect on children are no less serious than those of abuse. Children who are only neglected or both neglected and abused are more likely to have mental, behavioral, or emotional problems than children who are mistreated(Chen & Wang, 2003). Therefore, studies on child neglect are of great importance.

2.2. The Relationship Between Child Neglect and Social-Emotional Development

2.2.1 Defining Social-Emotional Development

Social-emotional development is a definition in psychosocial domain, which includes developmental changes in attachment, emotional, personality and identity, interpersonal relationships (Seifert &

Hoffnung, 2000; Lee, 2007 cited). Children and adolescents are exposed to environmental stresses that threaten healthy social adjustment and mental health. They also experience more serious stress than any other group due to changes in expected social roles, pressure to study, parent expectations and needs, reestablishment of parent-child relationships, and preparation for work (Yoo, 1996). In addition, LBCs or children in rural communities are subjected to psychological and emotional difficulties such as loneliness, anger, loss, anxiety or guilt due to a parent or parents migrate, or difficulties in expressing flight or deviant behavior in school life or interpersonal relationships (Bernardini & Jenkins, 2002; Choi, 2007).

Considering such circumstances, children must have resilience to cope with internal and environmental stresses without becoming

151

frustrated. Children or adolescents may suffer from difficulties such as conflict and stress; thus, the social adaptation ability of children and adolescents is necessary (Ji & Lim, 2011).

Park (2003) suggested that adolescents with high resilience develop meaning and purpose in life, feel happy in their relationships, are satisfied with themselves, and have a positive belief in the future.

This means that resilience is an important factor for adaptation, growth, and development in adolescents. In addition, the life satisfaction of adolescents is dynamic rather than static because it changes according to both individual internal factors and environmental factors (Fujita & Diener, 2005; Kim, Kim, &Kim, 2011, recited). In other words, it is useful to utilize life satisfaction to examine various environmental factors on social-emotional development of children and adolescents.

The sense of self-esteem also has a positive effect on adaptation.

Adolescents with a stronger sense of self-esteem are more likely to respond positively to stress (Han, 2004).

Social-emotional development has been described generally as the skills and behaviors that children need to adapt successfully to social settings (NCES, 2004; Gandolgor, 2013 cited). Children with behavioral problems, which are associated with social and emotional development, may result in the decline of their adaptation and future adjustment (Achenbach, 1991, Gandolgor, 2013 cited). Correspondingly, Gang, Yun, & Shin(2012) measured social-emotional development in regards to resilience, self-esteem, and life satisfaction in their study “influences of academic and social-emotional variables on school adjustment of junior high school students”, data used KCYPS. Kim (2011) also used KCYPS data studied “factors affecting the physical, social-emotional and cognitive development of child and youth in the ecological context - focusing on the differences between child and youth from single

161

female parent and two parent”, also used resilience and life satisfaction to measure social-emotional development.

In the present study, it examines youth social-emotional development when adapting to the environment, dealing with new relationships, and coping with stress. And the measurement scale also referenced KCYPS. So, self-esteem, resilience, and life satisfaction were studied in relation to social-emotional development of children and adolescents.To simplify the study, we try to use the sum of the three to measure the social-emotional development.

2.2.2 Literature Review of the Relationship Between Child Neglect and Social-Emotional Development

Parental absence, a consequence of parents’ rural-to-urban migration, often has considerable emotional costs on LBCs (Wen &

Lin, 2012). A number of studies have been conducted to test this relationship. Although the empirical results are somewhat mixed, most studies have documented the detrimental effects of parental migration on children’s emotion adaptation, such as feelings of loneliness, symptoms of depression and anxiety (Fan et al., 2010; Heet al., 2012;

Jia & Tian, 2010; Wu et al., 2015), and low levels of life satisfaction and happiness (Fan & Zhao, 2010; Liu &Oke, 2010; Su et al., 2012).

Moreover, researchers have further explored the differences in developmental outcomes between children with two migrating parents and children with just one migrating parent. For example, several studies have found that children with just a migrating father encounter less difficulty than children with two migrating parents, including lower levels of loneliness (Sun et al., 2010) and depression (Wang, Hu, &

Shen, 2011) and higher levels of life satisfaction (Fan et al., 2009).

171

Some studies, however, have not found any differences in loneliness and life satisfaction between children with two migrating parents and those with one migrating parent (Su et al., 2012; Zhou et al., 2005).

Considering the mixed findings on the influences of parent migration status on children’s emotional outcomes, further studies are needed to explore the variations in emotional adjustment among LBCs.

Resilience research suggests that risk factors are predictive of negative outcomes for only approximately 20–49% of a particular high-risk population (Lerner et al., 2009; Rutter, 1987; Werner & Smith, 2001), whereas protective factors appear to predict positive outcomes for approximately 50–80% of a high-risk population (Lerneret al., 2009). Although growing attention has been given to the well-being of LBCs and the protective factors associated with their resilience, the literature has mainly been based on deficit models focusing on problems and risk factors for LBCs.

Moreover, recent resilience research has focused on the social ecologies of resilience and underscored the importance of the cultural context in understanding resilience (Masten, 2014; Ungar, 2011). Thus, it is critical to identify specific protective factors that may cultivate well-being for LBCs by buffering the negative effects of parents’ migration in rural China.

2.3. The Moderating Effect of School Relationships on the Correlation Between Child Neglect and Social-Emotional Development

2.3.1 Defining School Relationships

For students, the most important school relationships are peer relationships and teacher-student relationships. The student’s teaching

181

and learning environment is important. The teaching and learning environment consists of the physical and socio-psychological environment of the classroom (Hwang, Eun, & Soon, 2008). The physical environment is an objective physical and structural environment. Psycho-social environment refers to the interaction between students and between teachers and students in the classroom (Lee, 2004).

In particular, peer attachment in adolescence becomes increasingly important as more emphasis is placed on relationships with friends, deviating from the tendency to rely solely on parent-child relationships in infancy and childhood. Weiss (1982) also suggests that adolescents maintain a more intimate relationship with friends who play an emotionally important role, and the level of peer attachment increases as teenagers share more time with their friends, along with the desire to be psychologically independent from their parents (Jo, 2010).

The relationship between the student and the teacher is composed of intimacy, trustworthiness, competence (Won & Park, 2010), understanding, sympathy, and esteem (Lim & Kim, 2004).

2.3.2 Attachment Theory

Attachment is an emotional or cognitive relationship between a person and his own self or between a person and others (Bowlby, 1980). For example, if a child has a stable attachment to the parents, then the child believes that the parents are meaningful and valuable in establishing a positive self-image. From the perspective of lifelong development, parental, peer, and teacher attachments are the most important.

Jeong (2006) stated that the impact of school is stronger in the current generation than previous ones, and knowledge comes less

191

from parents and more from school in modern times, schooling has played an important role in the socialization process of children and adolescents. Considering that the school is a place where children and adolescents spend a great deal of time, it functions as an important environment that contributes to the cognitive, social, and emotional development of children and adolescents. Therefore, peer and teacher- student relationships are also important factors to consider.

If the attachment relationship from the main caregiver is reliably and consistently supported from early childhood on, such relationships are then expected with other non-parent figures, and similar attachment styles are likely to form. In adolescence, children will experience the intimacy they felt with their parents in their relationships with peers who provide social and affectionate support.

Therefore, trust and support are related to attachment formation, and this plays as important of a role for peer relationships as for parental ones (Bartholomew & Horowitz, 1991; Hazen & Shaver, 1987). In modern times, parents are still an important attachment, but sometimes attachment to friends can replace attachment to parents (Jang, 1997).

Tian (2015) believed that the democratic teacher-student relationship is very beneficial to the development of LBCs whose parents are not present. Parents leave their children too early, resulting in the absence of family education for LBCs. Thus, school teachers then become temporary parental figures to make up for the lack of parental relationships in the child’s life. The formation of democratic teacher-student relationships enables rural teachers and LBCs to conduct dialogues and exchanges on an equal footing, and communication between teachers and students is based on trust and sincere exchange. The teacher recognizes the importance of the

201

student and impresses the student's mind so that the child can grow healthy and happy with confidence.

However, if excessive physical freedom is given to LBCs, there are then no reasonable restrictions. After rural parents migrate, the majority of LBCs are taken care of by grandparents. These guardians are often plagued by heavy farm work, lack of knowledge about science education, and poor communication with younger generations.

Therefore, the role of teachers in education and guidance is even more prominent.

2.3.3 Effects of Peer and -Student Relationships on Social-Emotional Development

Emotional support, interpersonal skills, recognition, and learning assistance obtained from peer relationships have a positive effect on the development of children (Park, 2005). The higher the quality of the peer relationship, the less loneliness children experience (Kim, Kim, &

Min, 2012). The better quality of peer relationship, the better the child’s adjustment to school life (Choi & Ji, 2003). Berndt (1999) found that children's school adaptation is influenced by the quality and stability of their peer relationships, and that when positive peer relationships increase, negative characteristics decrease.

Han (2012) found that for LBCs, the closer the peer and teacher-student relationships, the higher the children’s self-esteem scores. In a comparative study of parental, peer, and teacher relationships among children and adolescents, it was reported that teacher relations had a positive influence on school adjustment (Park, 2010; Park & Heim, 2005; Choi & Sin, 2003).

The teacher's educational duty is to develop students' resilience by meeting their needs in class, understanding them, and creating

211

positive relationships. Teachers should form positive student-teacher relationships not as a classroom management tool, but as a way to help students have the resilience to overcome pressures in school and society and to broaden the educational space (Kim, 2012).

2.3.4 The Moderating Effect of School Relationships on the Correlation Between Child Neglect and Soci al-Emotional Development

As mentioned above, in addition to family, experiences with friends also constitute an important developmental context for children (Rubin & Parker, 2006). As children become more cognitively independent from their parents from middle childhood to adolescence, peer relationship play an increasingly important role in children’s lives.

With peer relationships, children not only acquire opportunities for the expression and regulation of affection (Denton & Zarbatany, 1996;

Newcomb & Bagwell,1995; Salisch, 2000), but they also experience the security, emotional support, and confidence provided by social interactions (Wen & Lin, 2012) and display lower levels of loneliness and depression (Parker & Asher, 1993; Rubin et al., 2006).

Moreover, the potential therapeutic functions of friendship in the context of adversity were underscored in Sullivan’s (1953) theory of interpersonal relationships. Indeed, peer relationships and the support of friends have been found to help children avoid feelings of loneliness, inadequacy, or depression caused by social isolation (Laursen et al., 2007), peer victimization (Hodges et al., 1999; Woods, Done, & Kalsi, 2009), and childhood abuse (Powers, Ressler, &

Bradley, 2009). Given the increasing importance of friends in children’s lives during early adolescence, peer relationships may be particularly important for LBCs in adapting to the vulnerable situation

221

of parental absence, especially in the case of two migrating parents.

Notably, researchers of child resiliency have found that positive friendship may have a moderating effect on poor adjustment outcomes caused by a negative parent-child relationship (Gaertner, Fite, &

Colder, 2010; Gauze et al., 1996; Rubin et al., 2004). Rubin et al.

(2004) also found that having a strong supportive friendship buffered the negative effects of poor parent-child relationships on a child’s internalization of problems. These findings are consistent with social provision theory (Furman & Buhrmester, 1985), which suggests that high quality peer relationships may compensate for the risk effects of child neglect on social-emotional development in LBCs.

Teacher-student relationships can play a mediating role between parent-child attachment and subjective well-being of LBCs. Teachers are representatives of the adult world, respected and trusted by children, and LBCs can become emotionally dependent on them.

When dealing with children with absent parents, teachers can discover the children’s psychological problems, act as fathers or mothers, give comfort and guidance, and help them cope with their loneliness and loss.

Teachers are important figures in interpersonal relationships. Good teacher-student relationships are conducive to students actively participating in school life and developing a healthy personality. By establishing a harmonious and mutually beneficial relationship, students become more willing to participate in class activities. The intimacy of teacher-student relationship is negatively correlated with children's anxiety, social phobia(Liu, 2011). Thus, good teacher-student relationships play a positive role in solving the psychological problems of LBCs and are an urgent need in the present social reality.

The moderating roles of peer and teacher-student relationships on

231

the correlation between child neglect and social-emotional development in LBCs in their original rural communities should be further examined.

2.4. Summary and Analysis of Research Status

In other countries, the study of child neglect started earlier than in China, providing a plethora of research results on this topic. The current study primarily uses longitudinal research to suggest intervention measures for issues of child neglect. On the basis of the existing research results, some integrated institutions for child neglect have already been established for prevention and treatment. Using the cooperation of different areas of research, these institutions use new scientific methods such as counseling to help parents and providing children with neglect intervention guidance.

The study of child neglect by Chinese scholars is relatively new.

The existing research focuses on the fields of medicine, public health, and child abuse. Specialized research on child neglect has not yet been fully carried out. Pan is the only researcher to have studied the norm of child neglect, while the study of neglect for LBCs has been minimal.

In general, child neglect has not yet caused widespread concern in China. The current situation of neglected rural children and LBCs and the effects on social-emotional development should be studied in order to arouse public awareness and attention to child neglect, to ensure timely intervention, and to provide a healthy social and psychological environment for children's growth.

In addition, there is a close relationship between child neglect and social-emotional development, such as children’s self-esteem, resilience, life satisfaction, and social adaption, especially for LBCs. However, studies have not yet been conducted in China from this point of view,

241

and few studies have focused on the moderating effects of peer and teacher-student relationships. Therefore, this study examines the role of relationships in school in the hopes of providing information and a theoretical basis for future practice and policy.

251

Chapter 3. CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK AND RESEARCH HYPOTHESES

3.1. Conceptual Framework

The purpose of the present research is to examine 1) the differences in levels of child neglect between LBCs and non-LBCs, 2) the association between child neglect and social-emotional development, and 3) the moderating effect of peer and teacher-student relationships on social-emotional development of neglected children.

The figure 3-1A and figure 3-1B show the conceptual framework of this study.

The “Child Neglect and LBC Status Model” suggests that there are some differences in child neglect between LBCs and non-LBCs (see Figure 3-1A).

The “Child Neglect and Social-Emotional Development Model”

(see Figure 3-1B) is presented based on attachment theory and other previous studies (Zheng & Tao, 2001; Zhu, 2011; Han, 2012). This theory and previous studies suggest that child neglect can be associated with social-emotional development of LBCs.

The “Moderating Effect of Peer and Teacher-Student Relationship Model” is based on previous studies which found that peer and teacher-student relationships can be a protective factor for social- emotional development (Butler, 1997; Hawley & DeHaan, 1996; Walsh, 1996). Such studies suggested the moderating effects of peer and teacher-student relationships on the social-emotional development of neglected children (see Figure 3-1B).

261

271

3.2. Research Hypotheses

In accordance with the three main research questions, the following hypotheses were formulated.

Research Question 1: Is the level of child neglect higher for LBCs than non-LBCs?

Research Question 1-1: Is child neglect level of LBCs higher than that of non-LBCs?

Hypothesis 1-1: The child neglect level will be higher for LBCs than non-LBCs.

Research Question 1-2: What’s the difference of child neglect level among different LBC categories?

Hypothesis 1-2: When comparing LBC categories, the child neglect levels will be highest for children with two migrant parents rather than one migrant parent.

Research Question 2: What is the relationship between child neglect, sub-scales of child neglect, and social-emotional development?

Hypothesis 2-1: Child neglect will negatively affect social-emotional development; the higher the level of child neglect, the lower the social-emotional development will be.

Hypothesis 2-2: For the sub-scales of child neglect, the higher each sub-scale, the lower the social-emotional development will be.

Research Question 3: Do peer and teacher-student relationships moderate the effects of different types of neglect on social-emotional development among LBCs?

Research Question 3-1: Do peer and teacher-student relationships moderate the negative effects of child neglect on social-emotional development?

281

Hypothesis 3-1: Peer and teacher-student relationships will have a moderating effect on the social-emotional development of neglected children.

Research Question 3-2: Do peer and teacher-student relationships moderate the negative effects of sub-scales of child neglect on social- emotional development?

Hypothesis 3-2: Peer and teacher-student relationships will have a moderating effect on the negative relationship between sub-scales of child neglect and social-emotional development.

291

Chapter 4. RESEARCH METHOD

4.1. Research Procedures and Sampling 4.1.1 Research Design

In this cross-sectional study, purpose sampling procedure was used, which involved four steps for investigation and analysis. The first step was selecting a population for the purpose sampling survey; Juye, a rural county of Shandong province with a large laborer migration population, was chosen. LBCs are prevalent here and could reflect the typical features of LBCs throughout China. The county covers a geographic area of 1308 km2, included 427 villages, and had a population of 860,600 in 2012. The second step was choosing schools based on their location and the population density of Juye; participants from seven schools were surveyed by purpose sampling. Third, scales were arranged using purpose sampling according to the population density and corresponding quantity of LBCs living in each area.

Finally, the questionnaires were distributed to the schools.

Participants included LBCs and non-LBCs students ages 10 to 18.

Participation was voluntary and limited to students who were not suffering from cognitive disorders at the time of the survey, could communicate in Chinese, and were in higher levels of primary school or in secondary school. All participants underwent assessments for general information using the self-made “General Information Questionnaire.”

Child neglect was measured using “Development of neglect evaluation norms for 12–17 middle school students in rural areas of China” produced by Pan et al. (2014). Social-emotional development,

301

peer relationships, and teacher-student relationships were measured using Korean Children and Youth Panel Survey (KCYPS), The 7th Panel (2016) questionnaire for adolescents, which was based on the primary school Grade 4 and the secondary school Grade 1. Social- emotional development was assessed from three aspects: self-esteem (10 questions), resilience (14 questions), and life satisfaction (3 questions). Peer relationship was measured using fourteen questions.

Teacher-student relationship was measured using six questions.

4.1.2 Participants

The present study used purpose sampling. The plan was to collect 550 respondents from Juye in Shandong province, rural China.

Based on the “State Council Opinions on Efforts to Strengthen Care and Protection of Rural Left-Behind Children(China State Council, 2016)”, LBCs in rural areas were defined as having one or both parents who were migrant workers and unable to care for or live together with their children, causing the children (generally under 16 years of age) to be left behind. The target demographic was a) children ages 10 to 18, b) LBCs and non-LBCs, and c) students studying in higher level elementary school or junior-high school.

The criteria of participants were as follows. Inclusion criteria were respondents ages 10 to 18 living in rural China who were willing to participate, could read Chinese, could complete the test by themselves, and had no cognitive disorders. Exclusion criteria were children under 10 years old or more than 18 years old, those unable to read because of lack of knowledge (lower grade primary school children), or those with cognitive disabilities.

The sample size was calculated following the instructions by Ni et

311

al. (2010) in their paper, “Estimation of sample size for quantitative research in nursing research.” According to the authors, in order to explore the influencing factors of the variables, the measurement data sample size can be calculated using N = 4Uα2S2/δ2 where N is sample size, U is, S is standard deviation, and δ is allowable error.

After each factor was determined, N = 4×1.962×1.4272/0.252 = 500.

Taking into account the 10–15% loss rate and sampling error, the sample size was expanded to 550 people.

The survey was conducted in seven schools: four elementary schools and three junior-high schools in the rural areas where LBCs are highly concentrated. The survey was planned to be distributed to 550 students enrolled in grades 4, 5, and 6 in elementary school and grades 7 and 8 in junior-high school. Because students in grade 9 must prepare for the entrance exam, they were not surveyed in order to not disrupt their intense studying.

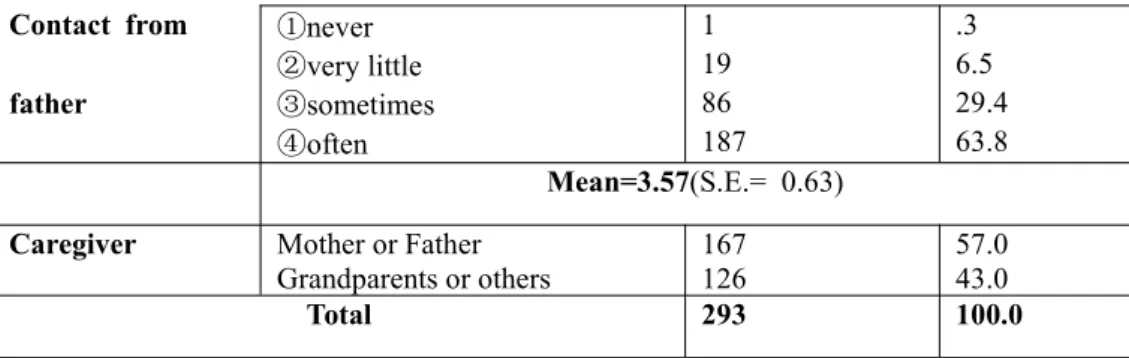

A total of 550 children from migrant and non-migrant families were invited, and 479 children were eventually selected for the study, Questionnaires returned incomplete (67) were excluded. Including 366 (76.4%) LBCs and 113 (23.6%) non-LBCs. However, if only the LBCs were analyzed, 293 were the analysis objects, and the missing 73 related control variables were removed. None of the participants had an observable physical or developmental disability. Other basic information is described later in this paper.

4.1.3 Data Collection

Data collection was implemented for approximately 3 weeks in December of 2017 in cooperation with seven schools, including both rural primary schools (grades 4, 5, and 6) and junior-high schools

321

(grades 7 and 8) in Juye County, China. After the schools granted permission to perform the study, the students completed the survey questionnaires, which were group-administered in their classrooms.

Written and verbal instructions were provided. The students were informed that there were no right or wrong answers and were assured of the voluntary and confidential nature of the study. There was no evidence that the participants had difficulties in understanding the procedures or the items on the questionnaire. Before administration of the study, informed consent was obtained from all children and their parents or guardians. If a student did not wish to participate, then they were not given a questionnaire, nor did they have to take the questionnaire home.

The questionnaire had a total of 210 questions covering general information, social-emotional development, peer relationship, teacher- student relationship, and child neglect. The survey took approximately 30 minutes to complete for junior high school students, and 90 minutes for primary school students. Administration of the questionnaire was supervised by the class teacher, and participants received a compensation when the questionnaire was completed. Due to the sensitive nature of certain questions, the school counselor was present during the survey process, and security instructions were provided to teachers who were responsible for administering and collecting the survey. After the survey, 546 consent forms and 479 questionnaires were collected, implying that 67 participants did not complete the survey. The 479 completed surveys were analyzed for this research. The response rate was 87.7% (479/546).

4.1.4 Research Procedures

This research plan and related materials were approved by the

331

Seoul National University Institutional Review Board, verifying that this study did not have a negative impact on the participants. The appropriateness, anonymity, and confidentiality were carefully reviewed for approximately one month to protect the well-being of participants.

The collected data and study sample were coded using numbers to protect the personal information of participants.

4.2. Measurement of the Variables

The variables in this research are illustrated as follows: dependent variable, independent variable, moderating variables, and control variables.

4.2.1 Dependent Variable: Social-Emotional Development

Children’s social-emotional development was defined using the Korean Children and Youth Panel Survey (KCYPS), which was modified by the 7th Panel (2016) questionnaire for adolescents based on the primary school grade 4 and the secondary school grade 1.

Social and emotional development include self-esteem(Rosenberg, 1965), self-resilience( Block & Kreman, 1996; Gwon, 2003), and life satisfaction(Kim et al., 2006). Responses were designed using the 4- point Likert scale for each item, ranging from strongly disagree to strongly agree, with scores ranging from a low of 1 to a high of 4.

Then, all scores for each index were added. A higher score indicated a higher level of self-esteem, self-resilience, and life satisfaction. For this research, all social-emotional development variables were considered continuous variables, and used the total score to measure social-emotional development.

341

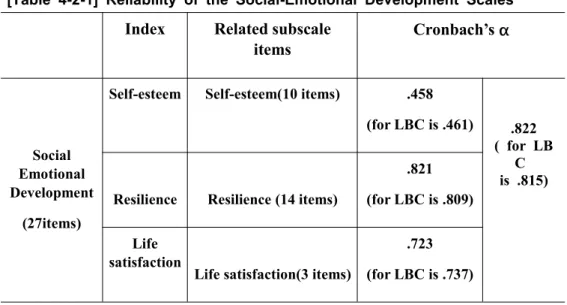

Table 4-2-1 shows each scale’s reliability, which was assessed using Cronbach’s alpha. The alpha coefficient of the present study was 0.822 for social-emotional development, .458 for the self-esteem sub-scale, .821 for the resilience sub-scale, and .723 for the life satisfaction sub-scale.

[Table 4-2-1] Reliability of the Social-Emotional Development Scales Index Related subscale

items Cronbach’sα

Social Emotional Development

(27items)

Self-esteem Self-esteem(10 items) .458

(for LBC is .461) .822 ( for LB

is .815)C Resilience Resilience (14 items)

.821 (for LBC is .809) satisfactionLife

Life satisfaction(3 items)

.723 (for LBC is .737)

4.2.2 Independent Variable: Child Neglect

Child neglect was defined in this study based on the scale from

“Development of neglect evaluation norms for 12–17 middle school students in rural areas of China” (hereinafter referred to as the norm) developed by Pan et al. (2014). The questionnaire consisted of a total of 59 items and each item was designed according to the 4-point Likert scale. Each question had 5 options: 1 = never, 2 = occasionally, 3 = often, 4 = always. If a question is a reverse score question, it is distinguished by adding "R" at the end of the abbreviation.The 1, 2, 3, and 4 options for the forward scoring question are given 1, 2, 3, and 4 points respectively; the scores for the reverse scoring question are

351

just the opposite of the scoring for the positive question, and are given to 4, 3, 2, 1, respectively. For the neglect evaluation norms (see Part 10), items were created from five different levels: physical neglect (PHN), emotional neglect (EMN), medical neglect (MEN), educational neglect (EDN), and safety neglect (SAN). These five indices of child neglect were used as continuous variables. The child neglect variable was not only used as the integrated scale with total scores, but also each sub-scale was considered as an independent variable.

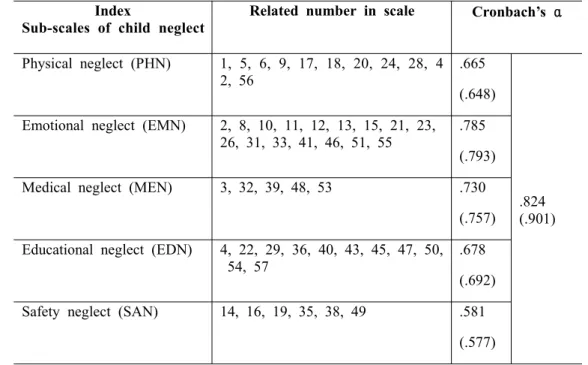

Table 4-2-2 shows this scale’s reliability, which was assessed using Cronbach’s alpha. The alpha coefficient in the present study was .824 for child neglect. The alpha coefficients for PHN, EMN, MEN, EDN, and SAN were 0.665, 0.785, 0.730, 0.678 and 0.581, respectively.

[Table 4-2-2] Reliability of Chinese Version of Child Neglect in Rural Areas Inventory

Index

Sub-scales of child neglect Related number in scale Cronbach’s α Physical neglect (PHN) 1, 5, 6, 9, 17, 18, 20, 24, 28, 4

2, 56 .665

(.648)

.824(.901) Emotional neglect (EMN) 2, 8, 10, 11, 12, 13, 15, 21, 23,

26, 31, 33, 41, 46, 51, 55 .785 (.793)

Medical neglect (MEN) 3, 32, 39, 48, 53 .730

(.757) Educational neglect (EDN) 4, 22, 29, 36, 40, 43, 45, 47, 50,

54, 57 .678

(.692) Safety neglect (SAN) 14, 16, 19, 35, 38, 49 .581

(.577)

361

In the present study, the 75th percentile of each neglect level score and the total neglect score as a boundary value (cut-off) were used to determine whether the child was neglected or not. Using these circumstances, child neglect rate was 48.6%. If the median was used as a boundary value, child neglect rate would be very high, at 79.1%.

Using the norm standard for neglect, each dimension’s cut-off scores were 25 for PHN, 37 for EMN, 11 for MEN, 26 for EDN, and 12 for SAN, and the total cut-off score was 108. For LBCs, according to 75% percentile, each dimension’s cut-off scores were 25 for PHN, 37 for EMN, 11 for MEN, 26 for EDN, and 12 for SAN, and the total cut-off score was 107.

If the total score of the tested child was higher than the adjusted score on the neglect scale, then he or she was categorized as a neglected child. The higher the score, the more serious the degree of neglect; the lower the score, the less serious. The evaluation methods for each level were also the same (Pan et al., 2014). If a child scored high for neglect at a certain level or scored consistently on many levels, then the child was categorized as neglected. If the total score exceeded the cut-off score, it was determined that the child was neglected (Pan et al., 2014; Liu, 2012). The neglect situation was reflected by the level of neglect.

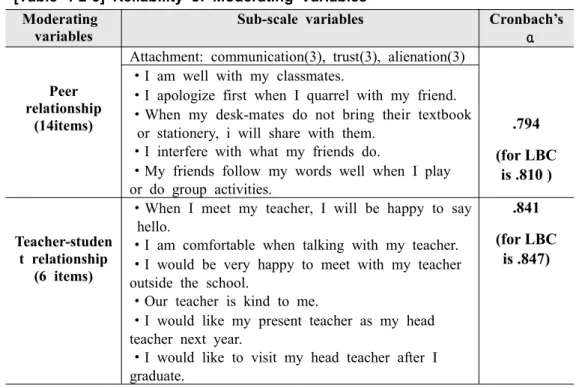

4.2.3 Moderating Variables

Peer and