저작자표시-비영리-변경금지 2.0 대한민국 이용자는 아래의 조건을 따르는 경우에 한하여 자유롭게 l 이 저작물을 복제, 배포, 전송, 전시, 공연 및 방송할 수 있습니다. 다음과 같은 조건을 따라야 합니다: l 귀하는, 이 저작물의 재이용이나 배포의 경우, 이 저작물에 적용된 이용허락조건 을 명확하게 나타내어야 합니다. l 저작권자로부터 별도의 허가를 받으면 이러한 조건들은 적용되지 않습니다. 저작권법에 따른 이용자의 권리는 위의 내용에 의하여 영향을 받지 않습니다. 이것은 이용허락규약(Legal Code)을 이해하기 쉽게 요약한 것입니다. Disclaimer 저작자표시. 귀하는 원저작자를 표시하여야 합니다. 비영리. 귀하는 이 저작물을 영리 목적으로 이용할 수 없습니다. 변경금지. 귀하는 이 저작물을 개작, 변형 또는 가공할 수 없습니다.

Doctoral Thesis in Ph.D. Medical Sciences

Analysis of Use Status After

Integration of Emergency Medical

Service Call System

Ajou University Graduate School

Department of Medicine

Analysis of Use Status After

Integration of Emergency Medical

Service Call System

Sang Chun Choi, Advisor

I submit this thesis as the

Doctoral thesis in Ph.D. Medical Sciences.

Fabruary 2019

Ajou University Graduate School

Department of Medicine

The Doctoral thesis of Chang Seong Kim in Ph.D.

Medical Sciences is hereby approved.

Thesis Defense Committee President

Joon Pil Cho Signature

Member Yoon Seok Jung Signature

Member Young Gi Min Signature

Member Sang Cheon Choi Signature

Member Choung Ah Lee Signature

Ajou University Graduate School

- ABSTRACT

-Analysis of Use Status After Integration of

Emergency Medical Service Call System

Emergency medical response system at the pre-hospital phase in Korea was originally divided into the 119 ambulance service under the Korean National Fire Agency and the 1339 Emergency Medical Information Center under the Ministry of Health and Welfare. However, with the amendment of the Act on the 119 Rescue and Emergency Medical Service by the National Assembly of the Republic of Korea in 2012, the 1339 Emergency Medical Information Center was closed. Instead, the 119 service has become a comprehensive center for medical emergencies (reporting an incident, dispatching the ambulance, hospital guidance, first aid guidance, and transferring the patient to an appropriate medical center) in an attempt to provide a “one-stop” service for patients. In addition, a 119 Emergency Control Center has been established and operates at the Korea National Fire Agency and its headquarters in different cities and provinces.

This study assessed pre-hospital phase emergency telephone call usage before and after the consolidation of emergency telephone numbers, analyzed the usage status by region and reasons for consultation after the stabilization of the Emergency Rescue Standard System (ERSS) operated by the 119 Emergency Control Center, and investigated the registered content of newly introduced cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) and first aid protocols after the consolidation of emergency telephone numbers.

Emergency Control Center and CPR and first aid cases registered in the Emergency Rescue Standard System (ERSS) – between January and December 2016 have been used for the analysis.

The following are the key outcomes of this study:

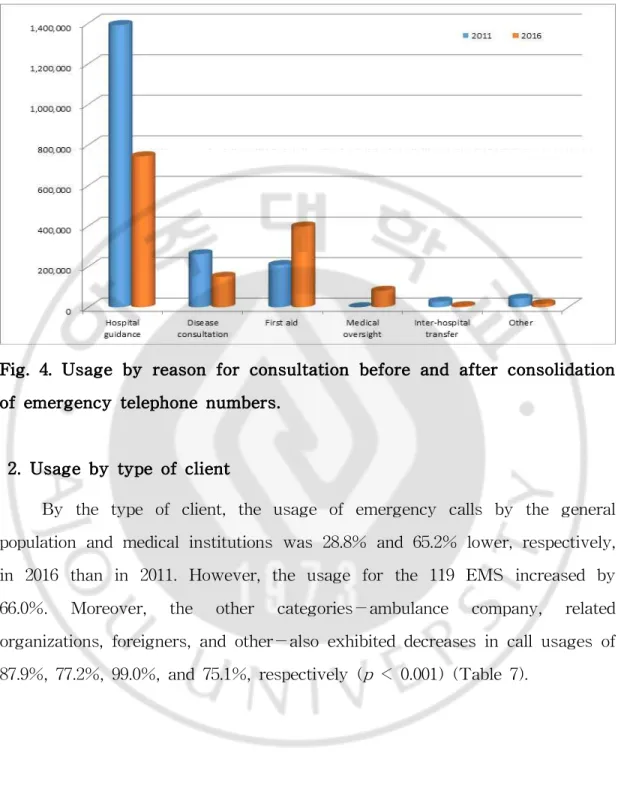

1. Since the consolidation of 119 and 1339 in June 2012, the overall operational performance of the 119 Emergency Control Centers has decreased by 27.8% compared to 2011, prior to the consolidation. Examining the reasons for consultation found that although the performance for first aid guidance has increased by 91.0%, consultations for disease management and hospital guidance have decreased by 42.5% and 46.5%, respectively.

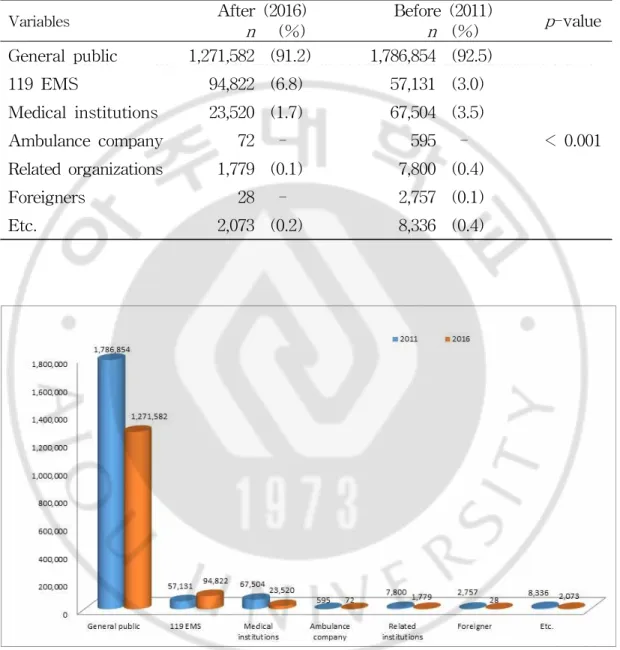

2. By client type, the usage by the general population, the highest usage rate, has decreased by 28.8%. Although the usage of the 119 emergency team has increased by 66.0%, usages by medical institutions, transporters, and related organizations have all decreased by 65.2%, 87.9%, and 77.2%, respectively.

3. By location, the city of Seoul showed the greatest frequency of usage with 305,942 cases. The usage per 1,000 people was greatest in the city of Daejeon (57.2 per 1,000 people) and lowest in the city of Changwon (11.5 per 1,000 people).

4. The mean age of patients with cardiac arrest who received CPR was 68.3 ± 18.7 years, and the majority of patients were in their 80s. Males exhibited more frequent cardiac arrest (11,710 patients, 60.2%) than females (7,729 patients, 39.8%). The main causes of cardiac arrest for different age groups were as follows: no breathing and suspected cardiac arrest without external cause for patients aged 70–80s; choking for those aged 40–50s; and suspected cardiac arrest from external damage (i.e., traffic accident or fall) for those aged 50–70s. CPR performers were mostly family members or

cohabitants (73.4%), followed by friends or acquaintances (9.1%) and facility participators (5.9%).

5. The time period between emergency telephone call (reporting of incident) and dispatcher-assisted CPR (DA-CPR) was 182.3 ± 89.8 seconds. Subjects who had CPR training showed a shorter time period (173 ± 88.6 seconds) than those who did not have training (184.0 ± 88.2 seconds).

The outcomes of this study demonstrated that although the usage status of consolidated 119 Emergency Control Centers has decreased in terms of overall operational performance compared to the previous system, the rate of first aid training (including CPR) via telephone has steadily increased since the consolidation of pre-hospital phase emergency medical service system. Therefore, studies or measures to provide more efficient and professional treatment instructions and improved quality of information are needed in the future. Enhancing the capability of the 119 Emergency Control Center will undoubtedly contribute to establishing an effective pre-hospital phase emergency medical service system.

Keywords: 119 Emergency Control Center, Cardiac Arrest(CA), Emergency Medical Service System (EMSS), Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation (CPR), Emergency Medical Dispatcher (EMD)

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Abstract ···ⅰ Table of contents ···ⅳ List of Figures ···ⅶ List of tables ···ⅷ Ⅰ. Introduction ···1A. Study background and purpose ···1

1. Study background ···1

2. Study purpose ···6

3. Definition of terms ···6

B. Scope of the study & Materials and Methods ···7

1. Scope of the study ···7

2. Subjects of the study ···7

3. Statistical analysis ···10

Ⅱ. Theoretical background of the emergency medical service system ···11

A. The concept of an emergency medical service system ···11

1. Significance of the emergency medical service system ···11

2. Management of the emergency medical service system ···12

B. Need for the emergency medical service system ···13

1. Need for the emergency medical service system ···13

C. Importance of cardiopulmonary resuscitation training ···29

1. Concept of CPR ···30

2. Definition of cardiac arrest (CA) ···30

3. CPR guidelines ···31

4. Status of rescue and emergency medical care training ···32

5. Status of the occurrence of cardiac arrest ···35

E. Foreign emergency medical service system ···35

1. The emergency medical service system in the U.S. ···35

2. The emergency medical service system in the U.K. ···38

3. The emergency medical service system in France ···40

4. The emergency medical service system in Germany ···43

5. The emergency medical service system in Japan ···46

Ⅲ. Results ···50

A. The status of emergency telephone call usage before and after the consolidation of emergency telephone numbers ···50

1. Usage based on the reasons for consultation ···50

2. Usage by type of client ···51

B. Status of the usage of the 119 Emergency Control Center before and after consolidation of emergency phone numbers ···53

1. Usage by region ···53

2. Usage by day of the week and time of day ···55

3. Usage per 1,000 people by region ···58

C. Status of the usage of CPR and first aid ···60

1. General characteristics of the patients ···60

3. Usage of emergency telephone calls by CA patients by time of day ···· 63

4. Relationship between CA patient and CPR provider ···65

5. Association between the cause of cardiac arrest and age ···66

6. The time period between reporting the incident and chest compression ···68

Ⅳ. Discussion ···70

Ⅴ. Conclusion ···78

References ···80

LIST OF FIGURES

Fig. 1. Chine of survival ···3 Fig. 2. Mimetic diagram of the emergency medical information & communication system in Korea ···19 Fig. 3. Emergency medical service report/registration system ···24 Fig. 4. Usage by reason for consultation before and after consolidation of emergency telephone numbers ···51 Fig. 5. Usage by type of client before and after consolidation of emergency telephone numbers··· 52 Fig. 6. Usage by region after consolidation of emergency telephone numbers. ···· 55 Fig. 7. Usage by day of the week after consolidation of emergency telephone numbers. ···56 Fig. 8 Usage by time of day after consolidation of emergency telephone numbers ··· 58 Fig. 9. Usage by the age group of cardiac arrest patients ···61 Fig. 10. Usage of emergency telephone calls by CA patients by month ···63 Fig. 11. Usage of emergency telephone calls by CA patients by day of the week ····63 Fig. 12 Usage of emergency telephone calls for CA patients by time of day ···65 Fig. 13. Relationship between CA patient and CPR provider ···66 Fig. 14. Association between the cause of cardiac arrest and age ···68

LIST OF TABLES

Table 1. Composition of emergency medical service system ···16

Table 2. Comparison of ranks and education process/duration of EMTs from different countries ···17

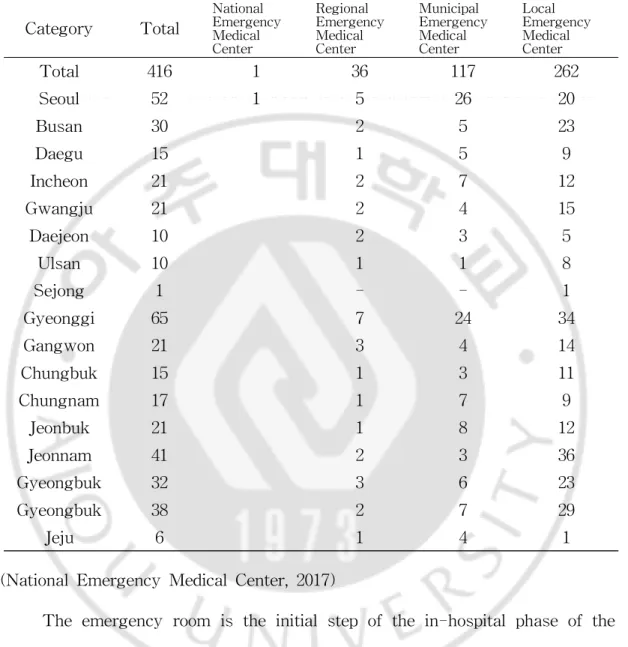

Table 3. Current status of emergency medical centers ···22

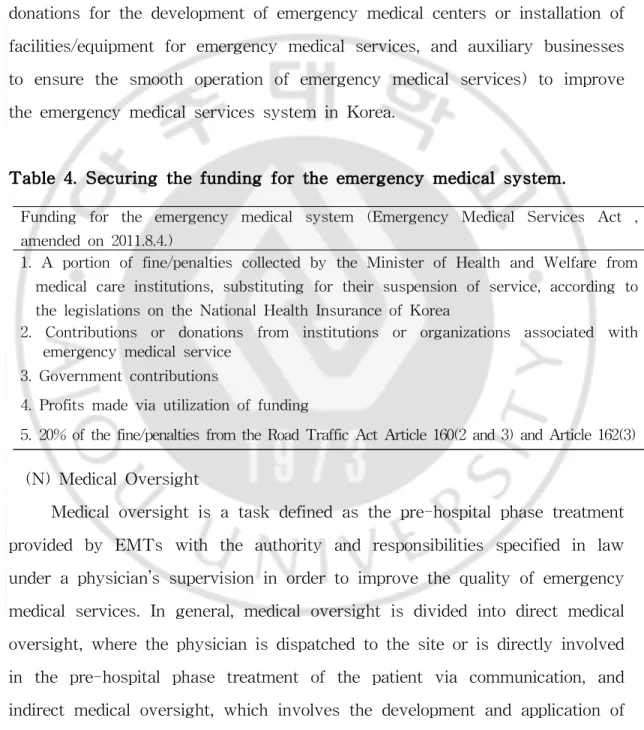

Table 4. Securing the funding for the emergency medical system ···28

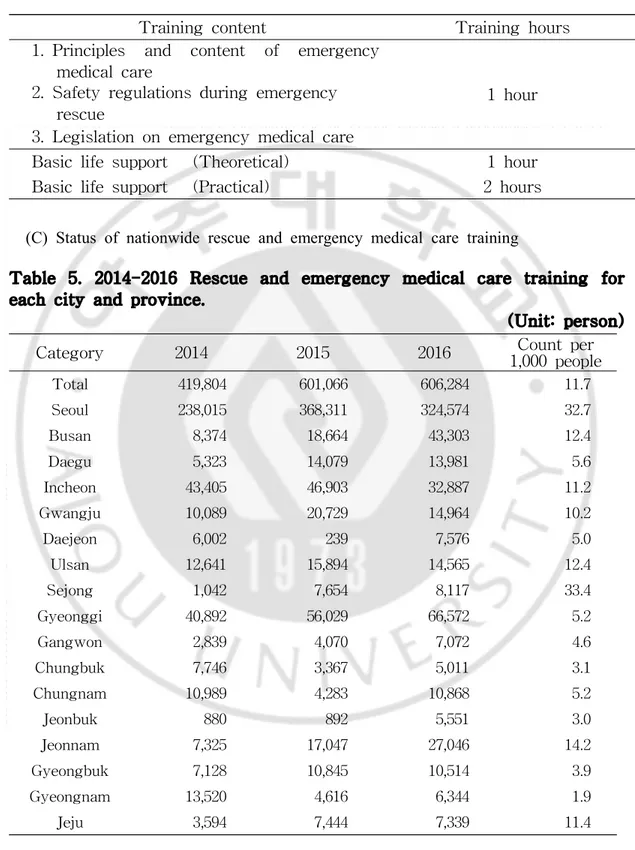

Table 5. 2014-2016 Rescue and emergency medical care training for each city and province ···34

Table 6. Usage by reason for consultation before and after consolidation of emergency telephone numbers ···50

Table 7. Usage by type of client before and after consolidation of emergency telephone numbers ···52

Table 8. Usage by region after consolidation of emergency telephone numbers. ··· 54

Table 9. Usage by day of the week after consolidation of emergency telephone numbers ··· 56

Table 10. Usage by time of day after consolidation of emergency telephone numbers ··· 57

Table 11. Usage per 1,000 people by region ···59

Table 12. General characteristics of the patients ···60

Table 13. Usage of emergency telephone calls by CA patients by month and day of the week ···62

Table 14. Usage of emergency telephone calls for CA patients by time of day ··· 64

Table 15. Relationship between CA patient and CPR provider ···65

Table 16. Association between the cause of cardiac arrest and age ···67

Ⅰ. Introduction

A. Study background and purpose

1. Study backgroundComplex social environment and changing life patterns in modern society are causing more emergency situations (disasters, acute disorders, intoxication, and accidents) that result in emergency patients. Therefore, there is an increasing interest in the general population regarding emergency medical care, as well as an increasing demand for emergency medical services. In addition, there is an increased demand for an improved quality of emergency medical care, with changing lifestyle and disease structure resulting in a remarkably increased number of emergency patients and a desire for improved quality of life accompanying economic development. Lastly, with an increasing number of workers working five days per week, more people will spend extra time on leisure activities, and therefore the number of traumatic accidents is expected to increase. Therefore, the establishment of an emergency medical service system at the national and regional levels must be completed with efforts from both the national and regional governments.

In South Korea, the pre-hospital phase emergency medical response system was originally divided into the 119 ambulance service under the Korean National Fire Agency and the 1339 Emergency Medical Information Center under the Ministry of Health and Welfare. However, with the amendment of the Act on the 119 Rescue and Emergency Medical Services

by the National Assembly of the Republic of Korea in 2012, the 1339 Emergency Medical Information Center was closed. Instead, the 119 service has become a comprehensive center for medical emergencies (reporting an incident, dispatching the ambulance, hospital guidance, first aid guidance, and transferring the patient to an appropriate medical center) in attempt to provide a “one-stop” service for patients. In addition, 119 Emergency Control Centers have been established and operate at the Korea National Fire Agency and its headquarters in different cities and provinces.

The 119 Emergency Control Center, pursuant to Article 10 (2) of the Act on 119 Rescue and Emergency Medical Services, is responsible for the following: hospital guidance, consultation and instruction for emergency patients; instructing the first aid protocol for the emergency patients in transit; providing information on the medical center where the patient will be transported; utilizing and providing information related to emergency medical care; and establishing, managing, and operating the 119 emergency-transportation-related information network. Since the consolidation of the 119 and 1339 systems, Emergency Medical Dispatchers (EMD) have been providing instructions for Dispatcher Assisted Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation (DA-CPR) and first aid information for patients with cardiac arrest.

The most important aspect in treating a patient with cardiac arrest is the role of the witness, since the occurrence of cardiac arrest is often not predictable and the patient cannot report the incident or go to a medical center by him/herself. Moreover, cardiac arrest most frequently occurs in one’s house, public areas, or athletic centers—usually far away from medical centers. Thus, a witness of cardiac arrest with no medical expertise should be able to inform the emergency medical service system immediately and

perform CPR as soon as possible. Within 4-5 minutes of cardiac arrest, the brain starts to suffer damage. Therefore, immediate CPR by a witness is essential to minimize brain damage, even if the patient recovers from cardiac arrest (Hwang SO et al., 2011). In order to improve the survival rate of emergency patients (including cardiac arrest patients), a system called the “Chain of Survival” is used. This concept, comprising early access, early Basic Life Support (BLS), early defibrillation, and early Advanced Cardiac Life Support (ACLS), needs all of its components working and flowing flawlessly to improve the chances of the patient’s survival (Lund et al., 2010). Early access and BLS are often performed at the pre-hospital phase, and the importance of appropriate treatment at this stage cannot be overemphasized (Moon JD et al., 2005).

Fig. 1. chine of survival.

Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation (CPR) is a technique to resuscitate a human body that is undergoing the process of death after cardiac arrest, and it contributes to saving lives from death caused by temporary and reversible reasons. Since its initial development as a simple method of ancillary circulation and respiration for humans with ceased heartbeat and respiration, CPR has become a comprehensive medical technique as a response to cardiac arrest, with development of resuscitation medicine in the past couple centuries

(Hwang SO, 2012).

CPR performed by the initial witness at the accident site has effects on the survival and prognosis of the patient with cardiac arrest (Connolly et al., 2007), and a previous study by Hanche and Waage indicated that the survival rate with CPR performed by a witness was 18.8%. In Korea, there are different reports showing different numbers, but the survival rate ranges between 2.5 and 7%. More specifically, a study by Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (KCDC) in 2008 showed that the survival rate of patients with cardiac arrest was 2.4%, which is remarkably low compared to the survival rates in developed countries (15–18%) where CPR is widely known. The rate of cardiac arrest witness performing CPR in Korea is merely 2–10%, while the rate in developed countries is 30–50%. This difference is likely the main reason for the low survival rate of patients with cardiac arrest (Hwang SO et al., 2011). The key reasons for low rate of CPR performance include inefficient training methods, lack of repeated training, lack of assessment after training, and the complex protocol of CPR (Cho JP et al., 2007).

Consolidation and separation of emergency telephone numbers may have different effects for reporters and service providers. From the reporter’s point of view, having fewer emergency telephone numbers makes it easier to remember them. However, for service providers, providing different types of services from a single telephone number may result in a reduced level of professionalism. Although several emergency telephone numbers have been consolidated so that only 112, 119, and 110 remain as of 2016, this only applies to the reporters and the traditional registration system, and telephone numbers from the service providers remained unchanged.

emergency telephone numbers (911 for the U.S. and 119 for Japan) and non-emergency numbers (311 for the U.S. and #7119 for Japan) so that the reporters can self-differentiate the level of emergency and use appropriate emergency centers. For less severe symptoms, the non-emergency number is used to obtain information regarding medical centers or medical consultation; this allows for the prevention of unnecessarily overpopulated emergency rooms and wastage of emergency medical team resources (Richard et al., 2009; Morimura et al., 2011). Nevertheless, as of 2012 in Korea, the emergency telephone number was consolidated into 119—a comprehensive center for medical emergencies (reporting an incident, dispatching the ambulance, hospital guidance, first aid guidance, and transferring the patient to an appropriate medical center)—in an attempt to provide a “one-stop” service for patients.

For cardiac arrest in emergency patients, it is difficult for general people to provide accurate and appropriate early response. Therefore, the Ministry of Health and Welfare, KCDC, and Korean Association of Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation (KACPR) recommend that the EMD should direct the witness over the phone to perform dispatcher-assisted CPR (DA-CPR) (Ministry of Health & Welfare, 2017). Although the rates are still low compared to those of developed countries, according to analyses of the statistics from 2006–2016 for acute cardiac arrest in Korea, the rate of CPR performed by witness has increased to 16.8% (2016), and the survival rate has increased to 7.6% (2016) (Kim YT, 2017). Since telephone-guided DA-CPR is one of the key methods to improve the rate of CPR performed by witness, comprehensive analysis and efficient future operation by 119 Emergency Control Centers are essential.

2. Study purpose

This study assessed pre-hospital phase emergency call usage before and after the consolidation of emergency telephone numbers, investigated the usage status by region and reasons for consultation after stabilization of the Emergency Rescue Standard System (ERSS) operated by the 119 Emergency Control Center, and analyzed the usage status of the 119 Emergency Control Centers for witness-performed CPR and first aid treatment with guidance from the newly introduced emergency medical dispatcher (EMD) after the consolidation of the telephone numbers, in order to provide an improvement plan for the system.

3. Definition of terms

(A) 119 Emergency Control Centers

119 Emergency Control Centers are established and operated at the Korea National Fire Agency and its headquarters at different cities and provinces. Based on Article 10 (2) of the Act on 119 Rescue and Emergency Medical Services, 119 Emergency Control Centers perform the following tasks: provide guidance and consultation for emergency patients, provide information for transporters regarding the first aid treatment and destination (medical center); provide information regarding emergency medical care and its utilization; and establish, manage, and operate the 119 emergency transportation-related information network.

(B) Emergency Medical Dispatcher (EMD)

Emergency medical dispatchers working at 119 Emergency Control Centers are responsible for providing guidance and consultation in emergencies. They are health care providers, 1st and 2nd class emergency

years of experience in providing consultation for emergency medical care at Emergency Medical Information Centers, based on the Act on 119 Rescue and Emergency Medical Services.

(C) Emergency Rescue Standard System (ERSS)

The Emergency Rescue Standard System (ERSS) is a firefighting and disaster management information system operated by the Korea National Fire Agency and its headquarters in different cities and provinces. The system provides comprehensive control of disastrous emergency events (fire, situations that require rescue activity, and emergency situations) from registration of the event to the 119 system and dispatch instructions to control of the situation.

B. Scope of the study & Materials and Methods

1. Scope of the studyIn this study, 19,439 cases comprising 119 Emergency Control Center usage cases and CPR and first aid cases registered in the Emergency Rescue Standard System (ERSS) between January and December 2016 were used for the analysis.

2. Subjects of the study

This study has three main components. First, emergency call usage before and after the consolidation of emergency telephone numbers was assessed. Second, the usage status by region and reasons for consultation after stabilization of the Emergency Rescue Standard System (ERSS) operated by the 119 Emergency Control Center were analyzed. Third, the registered content of newly introduced cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) and first aid protocols after the consolidation of emergency telephone numbers was

investigated.

(A) Assessment of the emergency call usage before and after the consolidation of emergency telephone numbers

Electronic record-based data of 1339 Emergency Medical Information Center from January–December 2011 prior to the consolidation of 119 and 1339 on June 2012, as well as the operational performance of the 119 Emergency Control Center in 2016, after the stabilization of ERSS, were analyzed. Prior to the consolidation, the statistical program for operational performance was on the same page as the consultation content report, broken down as follows: hospital guidance, disease consultation, guidance of emergency medical care, communication with ambulance dispatch, transfers between medical centers, and other. After consolidation, the following categories applied: hospital guidance, disease consultation, guidance of emergency medical care, guidance of medical care, transfers between medical centers, and other. Guidance of medical care prior to the consolidation was considered “disease consultation” or “guidance of emergency medical care,” while communication with ambulance dispatch was categorized as “other.” From the client’s perspective, data on the information center in the 2011 statistics and those on 129 were included as related organizations, while overseas residents and ships were categorized as other.

(B) Usage status of the 119 Emergency Control Center after consolidation of emergency telephone numbers

Prior to the consolidation, the 1339 Emergency Medical Information Center was operated by the Ministry of Health and Welfare, with 12 different regional offices at the following locations: Seoul (Seoul and Jeju regions), Busan (Busan and Ulsan regions), Incheon (Incheon region), Daegu (Daegu and Gyeongbuk regions), Daejeon (Daejeon and Chungcheong regions),

Gwangju (Gwangju and Jeonnam regions), Suwon (South Gyeonggi region), Uijeongbu (North Gyeonggi region), Jeonju (Jeonbuk region), Masan (Gyeongnam region), Wonju (West Gangwon region), and Gangneung (East Gangwon region). After the consolidation, pursuant to Article 10 (2) of the Act on 119 Rescue and Emergency Medical Services, the 119 Emergency Control Center and regional fire department headquarters worked together to enforce the Special Act on the Restructuring of Local Administrative Systems. Including the city of Changwon, one of the local governments in South Korea, 18 different fire department headquarters have been established and are being operated. The usage status of the 119 Emergency Control Centers in 2016 was analysed by region and reason for consultation, as well as the usage per 1,000 people.

(C) Usage status of CPR and first aid

Among 397,620 cases of emergency medical care guidance calls registered at the 119 Emergency Control Center between January and December 2016, retrospective analysis was performed on 19,439 CPR and first aid guidance call logs for emergency patients suspected of choking, no respiration, suffocation, foreign substance in airway, drowning, cardiac arrest from unclear external factor, or traumatic cardiac arrest from traffic accident or falling.

The date of the call is automatically given by the ERSS. Information regarding the age, gender, status of the patient, relationship between the patient and CPR provider (witness), and CPR provider’s status on previous CPR training were collected by the EMD via Q&A with the reporter (caller). If no response was given or no information was collected, the case was excluded from the study. If the patient was under cardiac arrest or similar condition, the reporter was asked to perform CPR according to the standard

manual developed by the Korea National Fire Agency. 3. Statistical analysis

The operational performance of the Emergency Medical Information Centers in 2011 was combined with computerized data of the emergency medical information system. Statistical analyses of the data from the 119 Emergency Control Center in 2016 were performed using Excel. Among performance data of CPR and first aid guidance, correlations among the categories with CPR guidance were statistically analyzed. Data obtained from this analysis were encoded and entered into SPSS ver. 18.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). For statistical analysis of continuous and categorical variables, t-tests and chi-square tests were used, respectively. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Ⅱ Theoretical background of the emergency

medical service system

A. The concept of an emergency medical service system

1. Significance of the emergency medical service systemIn an emergency medical service system, an emergency patient is defined as a patient with severe, life-threatening injuries or conditions (disease, childbirth, accidents, or injuries from disasters) that require immediate medical care to avoid fatal outcomes. The entire process from the moment that patient is under a life-threatening condition until recovery (or elimination of life-threatening factors)—which involves consultation, rescue, transportation, and emergency/medical care—is defined as emergency medical care. Since emergency medical care directly affects the patient’s life under emergency situations, the system needs to be very detailed and cohesive.

The Emergency Medical Service System (EMSS) is a re-distribution of human workforce, facilities, and equipment for efficient operation of these resources under different circumstances (i.e., emergency situations occurring in areas of different sizes). Appropriate emergency care at the site, rapid and safe transportation of the patient, and proper treatment (medical equipment and staff) at medical institutions are all vital components of the system. Therefore, in order to provide the best quality emergency medical service in the shortest period of time, the establishment of a co-operative system between the 119 emergency team, the 119 Emergency Control Center, and the medical center where the patient is being transported (and its emergency medical staff) is essential (Do BS et al., 2007).

citizens, including the rights to receive and be informed about emergency care, the obligation to report and assist with handling emergency patients, and exemption from responsibility for emergency care provided with good intentions. The rights and obligations of emergency medical care specialists include the following: the provision of treatment for patients who refuse emergency care or who are not emergency patients; prioritized emergency care for emergency patients; explanation and obtaining consent to receive emergency care; a prohibition on stopping emergency care; transportation of emergency patients; and a prohibition on hindering emergency care. The obligations of national and municipal governments include: the provision of emergency care; establishment and operation of emergency medical service system; operation of an emergency care committee; education on rescue and emergency care; establishment of an emergency care information network; financial support; evaluation of emergency medical care centers; and measures to be taken in case of multiple patients.

2. Management of the emergency medical service system

The emergency medical service system, depending on the location of emergency care service provision, largely consists of the pre-hospital phase and the in-hospital phase. The pre-hospital phase includes the reporting of emergency patients (119 report), dispatching the medical emergency team to the site, and transporting the patient to the medical center. The in-hospital phase includes continuous emergency medical care provided for the transported patient, emergency surgeries, and transfer to specialized emergency medical centers.

(A) Pre-hospital phase

(2) Providing dispatcher-instructed emergency care (first aid) until the ambulance reaches the site

(3) On-site emergency care provided by paramedics

(4) Determining the medical center for the patient to be transported to, via information sharing among the ambulance-emergency medical center-119 Emergency Control Center using an established information/communication network, and providing treatment on the way to the medical center

(B) In-hospital phase

(1) Examination of on-site treatment and provision of continuous emergency care

(2) Appropriate medical examinations to make diagnosis

(3) Determination of treatment method – hospitalization (general ward, ICU) or emergency surgery

(4) Determination of whether or not the patient requires transfer to a specialized emergency medical center (traumatic injury, burns, intoxication, or cardiovascular diseases) for optimal medical care, as well as the destination hospital (if the patient requires transfer)

B. Need for the emergency medical service system

1. Need for the emergency medical service systemThe increased number of automobiles and other means of transport is one of the results of industrialization and development in the modern era, along with a consequent increase in the number of accidents. In addition, modernization has resulted in an increased number of accidents of various other kinds (accidents during operations at companies, gas or fire in highly

populated residential buildings). These accidents inevitably produce casualties, and most of these patients require emergency care as soon as possible. Furthermore, the increased number of chronic degenerative diseases is another key factor that increases the demand for emergency care, as they result in cerebrovascular diseases (cerebral infarction) or ischemic heart diseases (Korea Institute of Health Services Management, 1996).

According to the National Statistics Office of Korea, the most frequent external cause of death is cancer, followed by cardiovascular diseases (52.5 deaths per 100,000 people in 2012). Cerebrovascular diseases are ranked third with 51.1 deaths per 100,000 people, and their incidence is increasing. The mortalities from traffic accidents, according to the 2011 National Competitiveness Report published by the Korean Ministry of Economy and Finance, was 2.9 per 10,000 automobiles—which was more than two-fold higher than the OECD average (1.3 people) or other countries such as the U.S. (1.4 people), France (1.2 people), or Australia (1.0 people), and more than three-fold higher than the U.K. (0.8 people), Germany (0.9 people), Japan (0.7 people), or Sweden (0.7 people). Despite its importance, there is a minimal level of interest in the emergency medical service system in Korea, unlike other developed countries or other medical specialties (Gwangju Metropolitan City, 2000).

In order for emergency patients to receive appropriate treatment at the right time, there are several things that need to be established (e.g., emergency care and specialist care at the site and in the ambulance, an emergency medical dispatch system that allows for rapid reporting of emergency accidents) to increase the public’s quality of life. In addition, in order to reduce the disability rate of emergency patients and improve survivability in trauma patients, an adequate emergency medical service

system that reflects the conditions in Korea needs to be developed. 2. Composition of the emergency medical service system

The composition of the emergency medical service system may change (additions or removals) based on the need for the element or changes in the medical care environment. In addition, the evaluation or analysis of management can allow for the improvement or emphasis of a particular component/element. In the modern era, the demand for specialized and high-quality emergency care is high. The establishment of an emergency medical service system in Korea was a relatively recent event, and currently the system is at the stage where evaluations for each component and improvements for weak components are taking place (National Emergency Medical Center, 2017).

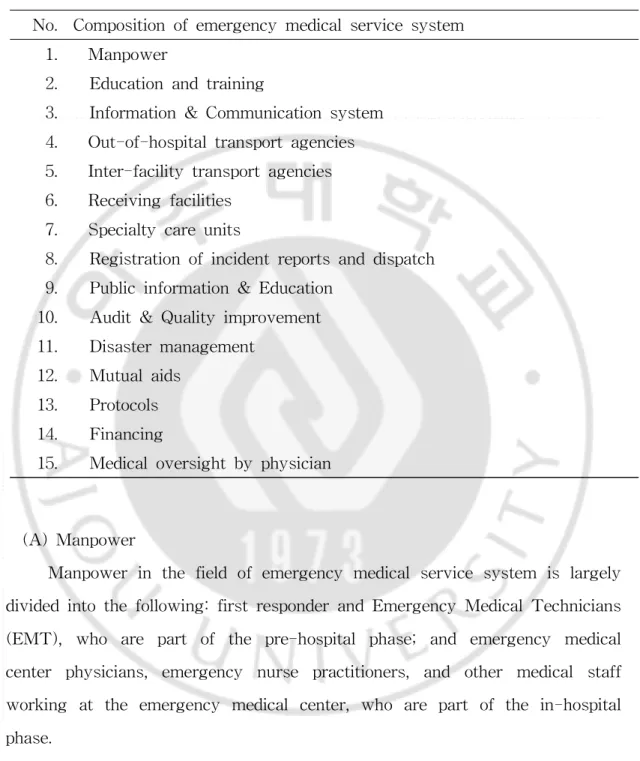

Table 1. Composition of emergency medical service system. No. Composition of emergency medical service system

1. Manpower

2. Education and training

3. Information & Communication system 4. Out-of-hospital transport agencies 5. Inter-facility transport agencies 6. Receiving facilities

7. Specialty care units

8. Registration of incident reports and dispatch 9. Public information & Education

10. Audit & Quality improvement 11. Disaster management

12. Mutual aids 13. Protocols 14. Financing

15. Medical oversight by physician

(A) Manpower

Manpower in the field of emergency medical service system is largely divided into the following: first responder and Emergency Medical Technicians (EMT), who are part of the pre-hospital phase; and emergency medical center physicians, emergency nurse practitioners, and other medical staff working at the emergency medical center, who are part of the in-hospital phase.

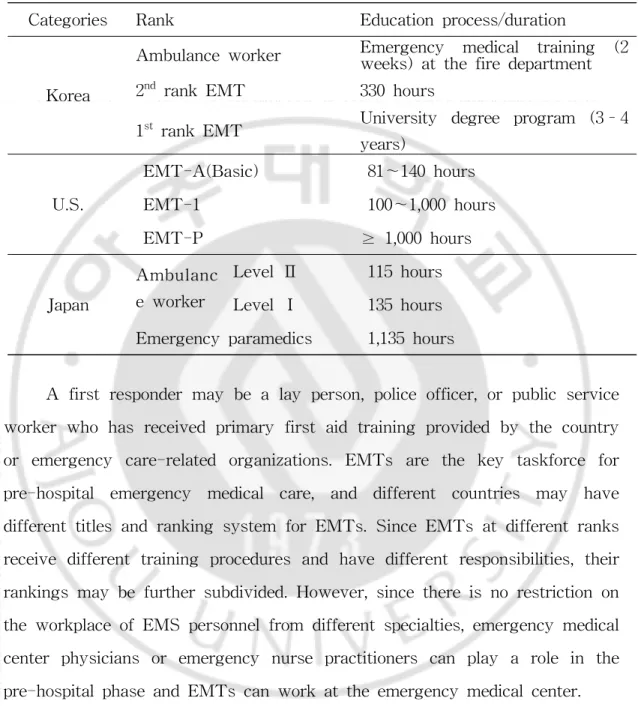

Table 2. Comparison of ranks and education process/duration of EMTs from different countries.

Categories Rank Education process/duration

Korea

Ambulance worker Emergency medical training (2weeks) at the fire department 2nd rank EMT 330 hours

1st rank EMT University degree program (3–4

years) U.S. EMT-A(Basic) 81〜140 hours EMT-1 100〜1,000 hours EMT-P ≥ 1,000 hours Japan Ambulanc e worker Level Ⅱ 115 hours Level Ⅰ 135 hours Emergency paramedics 1,135 hours

A first responder may be a lay person, police officer, or public service worker who has received primary first aid training provided by the country or emergency care-related organizations. EMTs are the key taskforce for pre-hospital emergency medical care, and different countries may have different titles and ranking system for EMTs. Since EMTs at different ranks receive different training procedures and have different responsibilities, their rankings may be further subdivided. However, since there is no restriction on the workplace of EMS personnel from different specialties, emergency medical center physicians or emergency nurse practitioners can play a role in the pre-hospital phase and EMTs can work at the emergency medical center.

(B) Education and training

In most cases, family members of the patient are the first responders. Therefore, providing education on basic CPR and trauma life support to these

lay people is important, aside from all other education and training (such as initial training, additional training, and mock exercises) required for public workers in the field of emergency care (the police, emergency care support centers, public health workers). Thus, the development of an appropriate educational program and securing well-trained lecturers are important to provide efficient education. Hiring personnel with complete training (certificates) for each speciality of emergency medical care will require an enormous amount of financial support from the government budget. Therefore, the development of the workforce via an independent educational system within the emergency medical service system relying on specialized academic societies for emergency medical care is more favorable. The appropriateness of the education should be frequently evaluated, and accepting feedback from the evaluations will improve the quality of the training program.

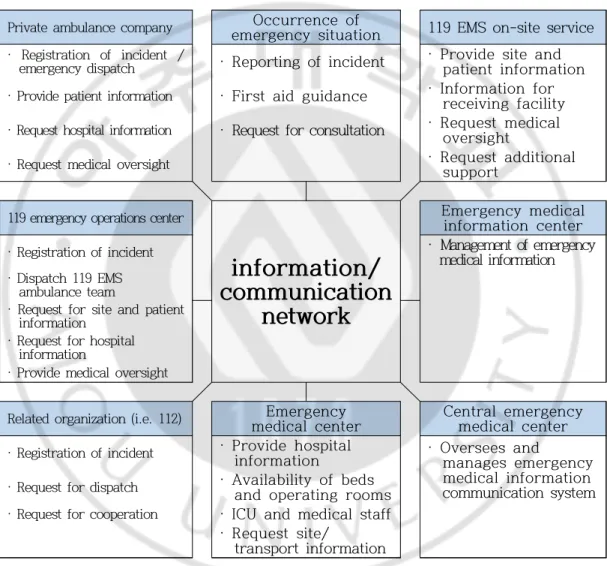

(C) Information & Communication system

In order to provide high-quality emergency medical service, the managers of each components of the emergency medical service system should be connected to work as a complete unit. The information and communication system is responsible for connecting the people in charge. Components of the communication system for emergency medical service include access, the registration of reported incidents and dispatch, and medical oversight.

Communication can be made via both landline and cellular (wireless) technologies. Although landlines traditionally constituted the major method, cellular phones are more widely used in the modern era, which can be very useful in emergency situations. The establishment of an information system via a communications network allows for not only the expansion of tasks that can be performed via communication, but also an increased quality of

emergency medical service. Information collected from different components of the emergency medical service using communications network can be utilized for research, evaluation, and medical oversight – therefore, the establishment of a stable information and communication system is an essential condition for advanced emergency medical service system.

Private ambulance company Occurrence of

emergency situation 119 EMS on-site service · Registration of incident /

emergency dispatch · Reporting of incident · Provide site and patient information · Provide patient information · First aid guidance · Information for receiving facility · Request hospital information · Request for consultation · Request medical oversight

· Request medical oversight · Request additional

support

119 emergency operations center

information/

communication

network

Emergency medical information center

· Registration of incident · Management of emergency

medical information · Dispatch 119 EMS

ambulance team

· Request for site and patient information

· Request for hospital information

· Provide medical oversight

Related organization (i.e. 112) Emergency

medical center Central emergency medical center

· Registration of incident · Provide hospital

information · Oversees and manages emergency medical information communication system

· Request for dispatch · Availability of beds

and operating rooms

· Request for cooperation · ICU and medical staff

· Request site/ transport information

Fig. 2. Mimetic diagram of the emergency medical information & communication system in Korea.

The Emergency Medical Dispatch system essentially applies to the first responder who can react practically instantly to the events occurring at the accident site. Since this system actively connects the patient, the witness, and

the EMT and adequately controls the tasks/resources needed in an emergency situation, it is also called the neural network of the emergency medical service system (James, 2002).

(D) Transport issues

The transportation of emergency patients is largely divided into out-of-hospital and inter-facility transports, and the transportation system is composed of the following: means of transport, number of people in the vehicle, emergency medical center, and information and communication. Means of transport include land (ambulance), air (airplanes, helicopters), and water (emergency medical boat) transport. Patients from sites in the mountain regions or islands, where it is difficult to reach them or it would take longer to transport the patient via land, will require air transport. Meanwhile, island countries or regions often utilize emergency medical boats for water transport. In Korea, there are two types of ambulances, general and specialty, based on the severity of the patient’s condition, while the U.S. operates three standardized types of ambulances. Air transport in Korea is operated by the 119 rescue center, and inter-facility transport is mostly performed via ambulances or private ambulances, which are not cost-free. The determination of the receiving facility should be primarily based on the distance between the site of the accident and the medical center, unless the patient requires special medical care offered only at certain medical centers. If the patient requires special treatment (e.g., emergency surgeries or cardiography/cerebral angiography), the patient should be transported to a medical center that offers these services. Medical oversight or information of the receiving facility during transportation should be available via the information and communication network between the ambulance and the medical center.

(E) Emergency medical centers (receiving facilities)

Emergency rooms in the emergency medical centers should have manpower and facilities to operate 24 hours a day in order to treat emergency patients who can come in at any time. In addition, information and communication equipment to share information with the ambulance, as well as separate ambulances for inter-facility transport need to be available.

Table 3. Current status of emergency medical centers.

(Unit: Number of centers) Category Total National Emergency Medical Center Regional Emergency Medical Center Municipal Emergency Medical Center Local Emergency Medical Center Total 416 1 36 117 262 Seoul 52 1 5 26 20 Busan 30 2 5 23 Daegu 15 1 5 9 Incheon 21 2 7 12 Gwangju 21 2 4 15 Daejeon 10 2 3 5 Ulsan 10 1 1 8 Sejong 1 - - 1 Gyeonggi 65 7 24 34 Gangwon 21 3 4 14 Chungbuk 15 1 3 11 Chungnam 17 1 7 9 Jeonbuk 21 1 8 12 Jeonnam 41 2 3 36 Gyeongbuk 32 3 6 23 Gyeongbuk 38 2 7 29 Jeju 6 1 4 1

(National Emergency Medical Center, 2017)

The emergency room is the initial step of the in-hospital phase of the emergency medical service system, and it should be designed to perform appropriate emergency medical treatments (e.g., triage, life support). Rankings of emergency medical centers are set primarily based on the availability of resources or specialty care. Emergency rooms in each hospital are evaluated by the national government according to the regulations of emergency rooms in light of the role of the emergency medical center. Considering the

population of the local community and the balance with nearby local communities, each emergency medical center is given a ranking and appropriate task. For consistent improvement of emergency medical centers, the development of standardized evaluation guidelines to assess the appropriateness of emergency medical care and financial support for the centers are mandatory.

In Korea, emergency medical centers are categorized into one of four categories: National, regional, municipal, or local emergency medical center. Long-term plans for establishment of treatment systems by emergency medicine specialists, quality improvements of the manpower in the emergency rooms, and the modernization of facilities/equipment in emergency rooms have been established. Each year, emergency medical centers are evaluated based on the above criteria, and different levels of financial support are provided based on the evaluation outcomes.

(F) Specialty care

In the emergency medical service system, the absence of specialty care centers that provide special medical treatments for patients in need of these treatment may result in confusion while determining the receiving facility or during inter-facility transport. This in turn may result in a lack of appropriate emergency medical care provided for the patient. Furthermore, it will be difficult to collect information regarding the number of patient or their prognosis, which may affect the planning or improvement of emergency medical services in the future. Therefore, analysis of the frequency (number) of patients and mortalities for neighboring regions needs to be performed prior to establishing a specialty care center at a prime location characterized by higher frequencies of accidents in nearby regions and better accessibility

to the center for the patients. In addition, a standardized transport-transfer protocol needs to be established beforehand in order to operate the center efficiently.

Currently in Korea, there are two specialty emergency care centers for pediatric patients and one specialty emergency care center for burns. In the future, the number of specialty care centers is expected to consistently increase.

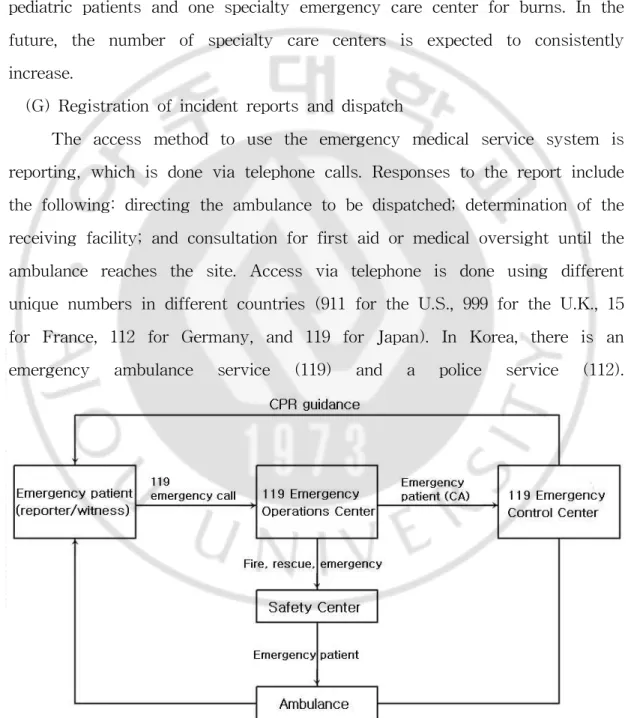

(G) Registration of incident reports and dispatch

The access method to use the emergency medical service system is reporting, which is done via telephone calls. Responses to the report include the following: directing the ambulance to be dispatched; determination of the receiving facility; and consultation for first aid or medical oversight until the ambulance reaches the site. Access via telephone is done using different unique numbers in different countries (911 for the U.S., 999 for the U.K., 15 for France, 112 for Germany, and 119 for Japan). In Korea, there is an emergency ambulance service (119) and a police service (112).

(H) Public information and education

Education for the public is mainly focused on the appropriate method to access emergency medical service, first aid protocols until the ambulance reaches the site, and appropriate measures for preventable traumatic injuries or diseases. These trainings will reduce the unnecessary utilization of the emergency medical service system, and therefore will help maximize the efficiency of the system. Training and education on first aid (primary first aid, basic life support) for the public needs to become more active. Furthermore, the national government should utilize mass-communication-based (TV, radio, Internet, or newspapers) advertisements to inform the public of preventive measures (e.g., the use of safety helmets) or information for emergency medical care (e.g., the prevention of influenza for specific seasons, food poisoning), at least against preventable traumatic injuries or diseases.

(I) Audit and quality improvement

In order to improve the emergency medical service system, evaluation and quality improvement of all components of the system regarding their medical accountability and appropriateness, as well as their cost-effectiveness, need to be performed constantly or regularly by the administration (government). Therefore, a standardized evaluation protocol for the following aspects needs to be developed: registration of incident reports and dispatch; responses; field assessment and treatment; and hospital outcomes.

The establishment of an electronic information system allows for these tasks to be more conveniently performed, as well as the improved quality of the emergency medical service system. Evaluation should not point out the faults of individuals, but rather reveal issues in the management of the

system in order to come up with improvements and provide positive feedback. (J) Disaster management

Since most disasters or large-scale accidents are accompanied by large numbers of casualties, the establishment of rescue plans as a part of the disaster prevention protocol is essential. The rescue plan should consider the characteristics of different regions based on the system utilized by local organizations for disease prevention (public organizations, emergency medical centers, and volunteer organizations). Afterwards, the administrative department for disease prevention should consider the plan and connect it with the disease prevention measures of other aspects to establish a nation-wide or region-wide disease prevention protocol.

Each emergency medical center should establish emergency plans for internal (regional or institutional) disaster and perform joint (with local organizations) or independent emergency drills. In addition, plans to store supplies for potential disastrous events – especially medical equipment and drugs – must be established and prepared under the support and control of the government.

(K) Mutual aid

For possible cases of disasters or large-scale accidents where emergency supplies from one regional facility are inadequate, or in cases where special equipment for emergency rescue is not available in the region, mutual aid plans between different regions must be established beforehand so that insufficient manpower/supplies can be accommodated from nearby unaffected regions. In general, these agreements are made under the government’s request or order – the unaffected region provides immediate

support, and the government provides financial support in the short future. (L) Protocols

Protocols for emergency medical service should be standardized so that specific treatments are given under specific circumstances. This protocol can be developed not only for the medical field but also for related personnel (managers or administrative assistants of emergency medical service system). The main focus of this protocol includes the standards for triage, treatment, transport, and transfer. The protocol for emergency medical service can be divided into the protocols that can be applied for both direct and indirect medical oversight and standing orders developed for indirect medical oversight – although standing orders are essentially a subset of the protocols. In other words, while the emergency medical doctor’s approval is required to perform a step in the protocol, the steps in standing orders can be performed without such approval. However, if the communication between EMTs and the physician is lost, EMTs should make decision on whether or not to perform the steps outlined in the protocol or standing orders, and these rights should be stated in law.

(M) Financing

For the improvement and development of emergency medical service system, diverse business plans and consequent financial support are mandatory. Financing the development of these new services is often from a tax-based system, but fees for using emergency medical service system and donations also contribute to this. Specific methods for financing include taxes (from liquor and tobacco), penalties for license registration, and government donations from a portion of the fines collected from various areas. Securing

and managing the funding is mostly legally regulated on the basis of Article 20 of the Emergency Medical Services Act of Korea. In addition, pursuant to Article 22, a portion of the medical cost of emergency patients is utilized for various business plans (money advances for outstanding balances, loans or donations for the development of emergency medical centers or installation of facilities/equipment for emergency medical services, and auxiliary businesses to ensure the smooth operation of emergency medical services) to improve the emergency medical services system in Korea.

Table 4. Securing the funding for the emergency medical system.

Funding for the emergency medical system (Emergency Medical Services Act , amended on 2011.8.4.)

1. A portion of fine/penalties collected by the Minister of Health and Welfare from medical care institutions, substituting for their suspension of service, according to the legislations on the National Health Insurance of Korea

2. Contributions or donations from institutions or organizations associated with emergency medical service

3. Government contributions

4. Profits made via utilization of funding

5. 20% of the fine/penalties from the Road Traffic Act Article 160(2 and 3) and Article 162(3) (N) Medical Oversight

Medical oversight is a task defined as the pre-hospital phase treatment provided by EMTs with the authority and responsibilities specified in law under a physician’s supervision in order to improve the quality of emergency medical services. In general, medical oversight is divided into direct medical oversight, where the physician is dispatched to the site or is directly involved in the pre-hospital phase treatment of the patient via communication, and indirect medical oversight, which involves the development and application of protocols, education/training and its evaluation, and quality assurance.

Direct medical oversight involves receiving direct orders from the physician to perform adequate first aid treatment via communication. Although this system has clearly defined medical responsibilities, the EMT’s ability to collect and analyze the patient’s information and efficiently communicate the information to the physician is essential for the medical oversight via communication to be effective.

Indirect medical oversight is a very comprehensive form of medical oversight—all other forms of medical oversight that are not a part of direct medical oversight are considered indirect medical oversight. By utilizing the standardized protocol of indirect medical oversight—a form of indirect medical oversight allowing the EMTs to perform basic first aid treatments without the direct oversight of a physician—direct medical oversight can complement indirect medical oversight (National Emergency Management Agency, 2014).

C. Importance of cardiopulmonary resuscitation training

One of the key aspects of the event of cardiac arrest is the role of the witness, since the occurrence of cardiac arrest is often not predictable and the patient cannot report the incident or go to a medical center by him/herself. Furthermore, cardiac arrest most frequently occurs in one’s house, public areas, or athletic centers, which are usually far removed from medical centers. Therefore, a lay person witnessing cardiac arrest should be able to inform the emergency medical service system immediately and perform CPR as soon as possible.

Within 4-5 minutes of cardiac arrest, the brain starts to suffer damage. Therefore, immediate CPR by a witness is crucial in minimizing brain damage in the event that the patient recovers from cardiac arrest. In general, from the onset of cardiac arrest caused by ventricular fibrillation, delayed

defibrillation reduces the survivability of the patient by 7–10% every minute. However, if the witness performs CPR, the reduction in survivability is reduced to 2.5–5% every minute. Moreover, cardiac arrest patients who received CPR from a witness exhibited a two-to-three-fold increased survival rate over patients who did not receive CPR. For a witness of cardiac arrest to perform proper CPR for the patient, the general population should be aware of the importance of CPR and receive basic education/training (Hwang SO et al., 2011).

1. Concept of CPR

CPR can be categorized into either Basic Life Support (BLS) or Advanced Cardiac Life Support (ACLS), but CPR in general indicates BLS. Recent technological advancements in automated defibrillators allow lay people to use the equipment, and consequently the process of utilizing automated defibrillators is included as a part of BLS. Witnesses who are unwilling to perform mouth-to-mouth respiration or who did not receive training on CPR may only perform chest compression, which is known as Compression-Only CPR (Hwang and Lim, 2016)

2. Definition of cardiac arrest (CA)

Cardiac arrest (CA) is defined as a state of no circulation due to the ceasing of the mechanical action of the heart. The World Health Organization (WHO) defines acute cardiac arrest or sudden cardiac death (SCD) as either a witnessed, unexpected death due to cardiac causes with loss of consciousness within an hour from the onset of symptom or a non-witnessed death preceded by 24 hours of normal life prior to the symptom. Acute cardiac arrest outside a hospital is a severe medical condition that requires

early response and treatment for better prognosis, and its prevalence and the survival of the patient are key indices reflecting the level of emergency medical service of a nation (Korea Centers for Disease Control Prevention, 2016).

3. CPR guidelines

The Ministry of Health and Welfare and Korean Association of Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation (KACPR) have developed a modified, newer version of the common CPR guidelines initially established in 2006 using new scientific evidence. This was to emphasize the importance of chest compression and simplify the CPR procedure so that anyone can perform CPR for the patient and improve the survivability of cardiac arrest patients. New guidelines have been established for the following topics: Ethics associated with CPR; chain of life; BLS including adult BLS; treatment of cardiac arrest; ACLS including treatment procedures of bradycardia and tachycardia; pediatric BLS; pediatric ACLS; neonatal BLS; and education/training. The key modifications include the following: changes in the order of BLS; introduction of chest-compression CPR; simplification of steps for assessing cardiac arrest and BLS; adjustment of chest-compression methods; and active recommendation of treatment after cardiac arrest.

(A) Changes in the order of BLS

In 2006 common CPR guideline, the recommended order of BLS was airway opening (A)-confirmation of breathing and resuscitation (B)-chest compression (C). However, in the 2011 Korean CPR guideline, the order of BLS was changed to C-A-B.

(B) Chest-compression (hand-only CPR)

training but are not confident in performing the entire process of artificial resuscitation and chest compression, and those who are unwilling to perform artificial (mouth-to-mouth) resuscitation are recommended to perform chest-compression-only CPR. Performing chest-compression CPR can simplify the entire process into three steps (confirmation of cardiac arrest—reporting the incident—chest compression), and therefore more people in general will be willing to perform CPR.

(C) Simplification of steps for assessing cardiac arrest and BLS

Witnesses of a suspected CA patient who has stopped breathing or was abnormally breathing (including CA respiration) are trained to identify the patient’s condition of CA. Removal of steps regarding confirmation of breathing (“listening-feeling-seeing”) has simplified the process of BLS.

(D) Adjustment of chest-compression method

In order to maintain an adequate level of chest compression depth and frequency, the recommended depth is a minimum of 5cm (5–6cm) in adults and 5cm in pediatric patients, while the recommended frequency is 100 compressions (100–120) per minute for both adults and pediatric patients.

4. Status of rescue and emergency medical care training

Article 14 of the Emergency Medical Service Act in Korea allows the Minister of Health and Welfare, mayor, and governor to require workers who are not in the emergency medical services field to receive basic training for rescue and emergency medical care.

(A) Subjects of emergency medical care training (1) Ambulance drivers

(2) Drivers of passenger vehicles, pursuant to Article 3(1) of the Passenger Transport Service Act

(3) School nurses/teachers, pursuant to Article 15 of the School Health Act (4) Police officers enforcing traffic safety, pursuant to Article 5 of the

Road Traffic Act

(5) Subjects who require safety and public health training, pursuant to Article 32(1) of the Occupational Safety and Health Act

(6) Medical workers, lifeguards, or safety workers at sports/physical training facilities, pursuant to Articles 5 and 10 of the Installation and Utilization of Sports Facilities Act

(7) Lifeguards pursuant to Article 22 of the Excursion Ship and Ferry Business Act (8) Medical workers, lifeguards, or safety workers in tourism industry,

pursuant to Articles 3(1)2–3(1)6 of the Tourism Promotion Act

(9) Medical workers, lifeguards, or safety workers in aircrews, pursuant to Articles 2(14)–2(17) of the Aviation Safety Act

(10) Medical workers, lifeguards, or safety workers among train workers, pursuant to Articles 2(10) A–D of the Railroad Safety Act

(11) Medical workers, lifeguards, or safety workers in ships’ crews, pursuant to Article 2(1) of the Seafarer’s Act

(12) Firefighting safety managers selected by a presidential decree, pursuant to Article 20 of the Act on Fire Prevention and Installation, Maintenance, and Safety Control of Fire-Fighting Systems

(13) Physical trainers, pursuant to Article 2(6) of the National Sports Promotion Act (14) Teachers, pursuant to Article 22(2) of the Early Childhood Education Act (15) ECE and day-care teachers, pursuant to Article 21(2) of the Infant Care Act

(B) Content and duration of emergency medical service training

(C) Status of nationwide rescue and emergency medical care training

Table 5. 2014-2016 Rescue and emergency medical care training for each city and province.

(Unit: person)

(National Emergency Medical Center, 2017)

Training content Training hours 1. Principles and content of emergency

medical care

1 hour 2. Safety regulations during emergency

rescue

3. Legislation on emergency medical care

Basic life support (Theoretical) 1 hour Basic life support (Practical) 2 hours

Category 2014 2015 2016 1,000 peopleCount per

Total 419,804 601,066 606,284 11.7 Seoul 238,015 368,311 324,574 32.7 Busan 8,374 18,664 43,303 12.4 Daegu 5,323 14,079 13,981 5.6 Incheon 43,405 46,903 32,887 11.2 Gwangju 10,089 20,729 14,964 10.2 Daejeon 6,002 239 7,576 5.0 Ulsan 12,641 15,894 14,565 12.4 Sejong 1,042 7,654 8,117 33.4 Gyeonggi 40,892 56,029 66,572 5.2 Gangwon 2,839 4,070 7,072 4.6 Chungbuk 7,746 3,367 5,011 3.1 Chungnam 10,989 4,283 10,868 5.2 Jeonbuk 880 892 5,551 3.0 Jeonnam 7,325 17,047 27,046 14.2 Gyeongbuk 7,128 10,845 10,514 3.9 Gyeongnam 13,520 4,616 6,344 1.9 Jeju 3,594 7,444 7,339 11.4

5. Status of the occurrence of cardiac arrest

The frequency and occurrence rate (per 100,000) people of pre-hospital phase acute cardiac arrest in Korea have steadily increased since 2010 (25,909 cases, 44.8 per 100,000), to 27,823 cases (44.7 per 100,000) in 2012, 30,309 cases (45.1 per 100,000) in 2014, and 30,771 cases (44.2 per 100,000) in 2015. In order to improve the survivability of pre-hospital phase CA, the Chain of Life—consisting of rapid assessment and report, CPR, defibrillation, effective ACLS, and comprehensive post-CA treatment working together—needs to be established (Korea Centers for Disease Control Prevention, 2016).

E. Foreign emergency medical service system

1. The emergency medical service system in the U.S.In the U.S., pre-hospital emergency medical care is provided by emergency medical technicians (EMTs) with the medical oversight of an emergency medical doctor. In general, EMTs have three ranks: Basic (EMT-B), intermediate (EMT-I), and paramedic (EMT-P). After completing the required training hours, they are eligible for certificate examinations to obtain or renew (maintain) their certificate.

Basic EMTs (EMT-B) receive 121 hours of training, and the main focus of the training is on patient assessment and safe transportation of the patient. Education in medical knowledge is limited to the level necessary to improve the efficiency of on-site medical care. EMT-B is the same level as an ambulance worker in Korea. Intermediate EMTs (EMT-I) are an intermediate level between EMT-B and paramedics. Experienced EMTs receive more extensive training on specific emergency medical treatments

(tens to hundreds of hours for training) and are given specific tasks. The training procedure for EMT-I’s is a part of the training program for paramedics. Therefore, in addition to the emergency medical treatments that can be performed by EMT-B’s, EMT-I’s can perform additional tasks (e.g., securing IV path, utilizing MAST, and defibrillation). Paramedics (EMT-P) are a highly trained workforce who can perform advanced emergency medical treatments of patients under life-threatening conditions. In addition to emergency medical care, all emergency situations are reported to the single telephone number of 911. The EMD directs the call to the appropriate department based on the characteristic of the report (occurrence of patient, onset of fire, or occurrence of crime). The main advantage is that police, ambulance (medical team), and firefighters can be dispatched simultaneously in cases where all three are needed.

Since mediate response to every report made to 911 results in a massive waste of resources, larger cities have another emergency telephone number, 311, for less urgent cases where the reporting individual can self-identify the severity of the incident, which can report accordingly to separate the cases based on their severity. This allows for the accommodation of different types of demands for emergency medical care (medical consultation for self-diagnosis and onset of mild symptoms at night), on top of preventing emergency medical service resources being wasted or emergency rooms being filled with patients with mild symptoms due to a lack of communication. Although 911 and 311 are separate numbers, the EMD is the same individual. Based on the judgment of the EMD, an ambulance may be dispatched even if the report was made to 311 (Park KJ, 2014).

Although the affiliation, scope of tasks, and standards of EMTs vary among different states, there is a minimum standard level. While most EMTs receive direct medical oversight from physicians, EMTs can perform on-site treatments or tasks without medical oversight in special cases (e.g., short transportation periods in metropolitan cities). Since most EMTs are highly trained, there are no issues with on-site emergency medical treatment provided by EMTs. More specifically, paramedics (EMT-P) are very highly trained so that they can provide an expert level of emergency medical care.

The main agency responsible for the transportation of patients varies among states and regions, but fire departments, private ambulances, and departments of public health in the state government are the main examples. The scope of on-site treatment, ranging from BLS to ACLS, also varies across regions but is often evaluated by higher-level monitoring organizations based on medical evidence. Identified problems or issues are reflected in the performance evaluation. While patients with moderate emergency conditions are transported to nearby emergency medical centers, patients with severe traumatic injuries are remotely transported to the nearby level 1 trauma center.

The main characteristics of general emergency medical service system in the U.S. are that, in addition to pre-hospital emergency medical services provided by public organizations (like the 119 emergency medical care team in Korea), the role of private or hospital-affiliated emergency medical care teams is highly significant for inter-facility transport. In the U.S., all emergency medical care teams regardless of their affiliation (for example, 911 ambulance teams from fire departments or private companies) receive partial financial support from the federal and state governments. In addition to financial support, they are under appropriate yet strict management and

regulation by these governments in terms of their operation and EMT management and training (Goldberg, 1990). The medical cost of the pre-hospital emergency medical service is billed to the patient (including the transport fee) and there are multiple health insurance plans available for the general population, allowing the patient to choose beforehand. Furthermore, the social security system for the elderly, infirm, or poor people ensures that no patient under life-threatening conditions is denied of emergency medical service because of medical cost.

In order to promote the participation of the general population in the emergency medical service system, Good Samaritan laws have been enacted to ensure that no legal charges will be filed against individuals who provide emergency medical care to a patient under life-threatening conditions, where the help was voluntary and not for monetary compensation. Moreover, there are other policies to promote the participation of people in the emergency medical service system, such as approving business permits only if a set portion of the employees have certificates of emergency medical training (for limited types of business).

2. The emergency medical service system in the U.K.

During the pre-hospital phase, the physician is not in the ambulance. When there is a reported incident of an emergency patient to 999, the EMD registers the incident based on its characteristics (emergency medical service, firefighting, or police services). For the calls directed to the emergency medical service, EMTs make a judgment and connect to a local ambulance service center if emergency medical service is needed. The ambulance service center, based on the patient’s condition, gives dispatch orders if on-site emergency medical treatment is required. The location of the cellphone used