Articles published in Obstet Gynecol Sci are open-access, distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (http://creativecommons.

org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/) which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Copyright © 2015 Korean Society of Obstetrics and Gynecology

Case Report

Obstet Gynecol Sci 2015;58(4):323-326 http://dx.doi.org/10.5468/ogs.2015.58.4.323 pISSN 2287-8572 · eISSN 2287-8580

www.ogscience.org 323

Introduction

Castleman and Towne [1]. first described giant cell mediasti- nal lymph node hyperplasia in 1954 and defined Castleman’s disease (CD) as a rare benign proliferation of mediastinal lymphoid tissues with unknown etiology. It has a peak age of incidence in the third and fourth decades. In addition, 70% of CD is found in the mediastinum and it is uncommonly found in neck, pancreas, or pelvic cavity [2]. Keller et al. [3] reported over than 80 cases and provided evidence of the lymph node hyperplasia found in sites other than mediastinum. The au- thors revised the definition of CD to include extramediastinal lymph node hyperplasia. However, only few cases of pelvic CD have been reported and these were often misdiagnosed as an adnexal mass [4-6]. We represent a case of asymptomatic CD in a young woman in which the lesion was initially diagnosed as an ovarian tumor and review the clinicopathological find- ings in a presentation of CD.

Case report

A 27-year-old woman was referred to our hospital for a pelvic mass detected by transvaginal ultrasonography. She denied any systemic symptoms such pelvic pain, fatigue, fever, or weight loss. Physical examination was unremarkable and there were

no swollen lymph nodes in neck, axillaries, and inguinal area.

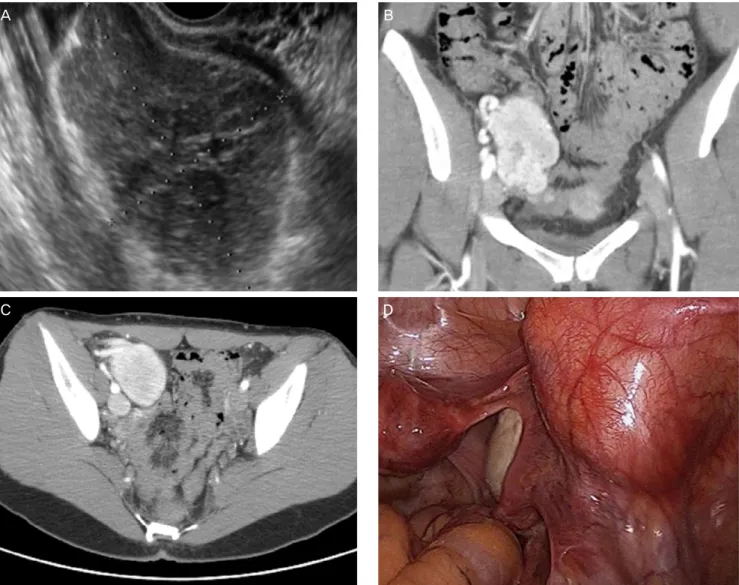

Blood tests including CA-125 showed no evidence of inflamma- tion, infection, or malignancy. Chest X-ray revealed no abnormal findings. Transvaginal ultrasonography detected 7×5-cm-sized hyperechoic mass adjacent to the right ovary (Fig. 1A). Following computed tomography scanning of the abdomen showed about 7-cm-sized mass on the right extraperitoneal pelvis with bilateral external iliac lymph node enlargement (Fig. 1B, 1C). The patient underwent single-port access laparoscopic surgery with the initial impression of benign neoplasm of either lymph node or right ovary. Briefly, after making a 1.5-cm vertical intra-umbilical skin incision, a wound retractor was inserted into the peritoneal cavity through the umbilicus. A 7 and a half surgical glove was fixed to the outer ring of the wound retractor. After making small inci-

Received: 2014.12.3. Revised: 2015.1.6. Accepted: 2015.1.19.

Corresponding author: Jiheum Paek

Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Ajou University School of Medicine, 164 World cup-ro, Yeongtong-gu, Suwon 443-380, Korea

Tel: +82-31-219-5250 Fax: +82-31-219-5245 E-mail: paek.md@gmail.com

Pelvic Castleman’s disease presenting as an adnexal tumor in a young woman

Jisun Lee

1, Jiheum Paek

1, Yong Hee Lee

2, Tae Wook Kong

1, Suk-Joon Chang

1, Hee-Sug Ryu

1Departments of 1Obstetrics and Gynecology, 2Pathology, Ajou University School of Medicine, Suwon, Korea

Castleman’s disease (CD) is a rare benign disorder of unknown etiology characterized by proliferation of lymphoid tissues. Seventy percent of this tumor occurs in the mediastinum and it is seldom found in neck, pancreas or pelvis.

We report a case of asymptomatic pelvic CD initially presenting as an adnexal tumor in a 27-year-old woman. Initial transvaginal sonography revealed 7-cm-sized hyperechoic mass adjacent to the right ovary and the following abdominal computed tomography scanning showed the same sized mass located on the right extraperitoneal pelvic cavity. Laparoscopic mass excision was performed without any complication and pathological diagnosis was made as CD. CD should be included in the differential diagnosis of female pelvic masses which are noted in the pelvic cavity. In this report, we review the clinicopathological findings in a presentation of CD.

Keywords: Adenxal tumor; Giant lymph node hyperplasia; Pelvis

www.ogscience.org 324

Vol. 58, No. 4, 2015

sions in the finger tip portions of the glove, three 5-mm trocars were inserted. Laparoscopic exploration revealed grossly normal uterus and bilateral ovaries. There was 7-cm-sized pelvic mass, most likely to be lymph node enlargement at the right external iliac area (Fig. 1D). A laparoscopic monopolar device was applied to excise the pelvic peritoneum to expose the pelvic mass, and then bipolar device was applied to ensure coagulation around the tumor. Although it was closely located to the external iliac vessels, there was no direct vascular invasion noted in the tumor and the surface of the tumor was well circumscribed and rub- bery firm. Therefore, we could dissect the tissues around the tumor and desiccate the feeding vessel from the external iliac artery without hemorrhage. After the tumor was put in a laparo- scopic bag, it could be removed by manual morcellation through

the umbilicus without tumor spillage. No enlarged lymph nodes were found at the retroperitoneal region and pelvic lymph node dissection was not performed.

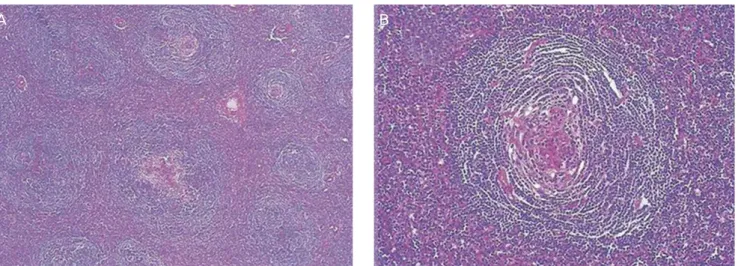

On gross examination, the surface of the specimen was well circumscribed and rubbery firm. The cut surface appeared soft, finely granular, and pale yellow in color. Microscopic examination demonstrated multiple mature lymphoid follicles with a hyalin- ized germinal center in an onion-skin arrangement, which was consistent with the hyaline-vascular type of CD (Fig. 2).

The patient recovered without any complication and she was discharged three days after the surgery. Abdominal computed tomography scanning at three months after the surgery showed no evidence of recurrence.

Fig. 1. About 7-cm-sized mass at right extraperitoneal pelvis. (A) Transvaginal ultrasonography. (B,C) Abdominopelvic computed tomography. (D) Intraopera- tive finding.

A B

C D

www.ogscience.org 325

Jisun Lee, et al. Castleman’s disease in the pelvis

Discussion

CD is a rare benign neoplasm of lymph nodes with unknown etiology. Since Castleman and Towne [1] had reported the first case, there have been reports of lymph node hyperplasia outside the mediastinum and CD now includes extramediasti- nal lymph node hyperplasia [3]. The clinical manifestations of CD are heterogeneous ranging from asymptomatic to diffuse lymphadenopathy with severe systemic symptoms [7]. Histo- pathologically, CD is classified into the hyaline vascular variant (HVV), the plasma cell variant, and vascular-plasma cell variant [3]. The HVV type of CD is generally presented in unicentric pattern with a disease confined to a single anatomic lymph node-bearing region. The HVV types have been usually asymp- tomatic. Multicentric presentation is commonly found in the plasma cell variant type, which is characterized by generalized lymphadenopathy, systemic symptoms, hepatosplenomegaly and a more aggressive clinical course with the potential for malignant transformation [3,7].

The etiology of CD is still unclear, but several factors have been proposed to be associated with the development of CD, which include chronic low-grade inflammation [1], an im- munodeficient state [7], and autoimmunity [8,9]. Especially, a large body of evidence has supported the importance of infec- tion with human herpesvirus 8 or Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpesvirus in the etiology and management of multicentric CD. In multicentric CD, human herpesvirus 8 can be detected in plasmablastic cells [10,11]. Furthermore, Interleukin-6, a multifunctional cytokine known to affect tumor growth and

angiogenesis, has been implicated as a contributing factor to the development of CD [9]. Nishi et al. [12] found that CD patients had higher vascular endothelial growth factor concen- tration than normal control, suggesting blood vessel prolifera- tion may be associated to the pathogenesis of CD. In present time, surgical excision is the standard therapy. However, many studies have suggested cytoreductive surgery followed by che- motherapy and radiation therapy as the potential treatment option for the disease. However, the effectiveness has not been proved yet and further studies must be required to make a concrete guideline for the treatment of the disorder. Our patient had unicentric CD of the HVV type without symptom.

This mass occurred in the retroperitoneal region adjacent to the lateral pelvic wall with vascular supply from the iliac ves- sels. The hypervascularity is commonly associated with a heavy bleeding at excision [13,14]. Moreover, dense fibrous adhesion to the pelvic vessels or pelvic wall can make it difficult to per- form a surgical removal [14,15]. To avoid massive hemorrhage, it is essential to fully dissect tissues around the tumor and have enough space to desiccate the feeding vessel originated from large vessel.

There were a few reports of CD found in female pelvis, which resemble clinical characteristics of tubo-ovarian abscess, endometriotic cysts, or dermoid cyst of ovarian origin. Despite the low incidence of CD in female pelvis, because of the clini- cal resemblances of other pelvic mass, it may be difficult to diagnose CD from initial evaluation and may be considered to be included in the differential diagnosis of pelvic mass.

Fig. 2. Microscopic examination showing Castleman’s disease representing hyaline-vascular type. (A) Multiple lymph node hyperplasia (HE, ×200). (B) Hya- linized germinal center (HE, ×400).

A B

www.ogscience.org 326