Korean Circulation Journal

Introduction

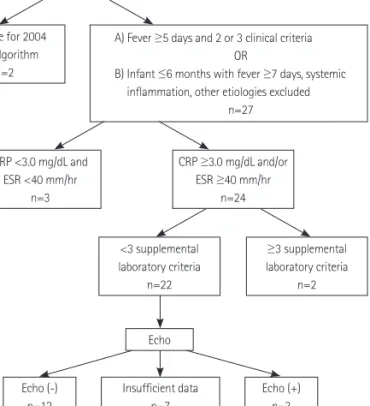

The etiology of Kawasaki disease (KD) is still unknown and no sin- gle pathognomonic clinical or laboratory finding for its definitive diagnosis has been identified. To establish a diagnosis, we inevita- bly depend on the diagnostic criteria that include the typical con- stellation of symptoms and signs noted by the Japanese Kawasaki

Print ISSN 1738-5520 • On-line ISSN 1738-5555

Diagnosis of Incomplete Kawasaki Disease in Infants Based

on an Inflammation at the Bacille Calmette-Guérin Inoculation Site

Ji Hye Seo, MD 1 , Jeong Jin Yu, MD 1 , Hong Ki Ko, MD 1 , Hyung Soon Choi, MD 2 , Young-Hwue Kim, MD 1 , and Jae-Kon Ko, MD 1

1

Department of Pediatrics, College of Medicine, University of Ulsan, Seoul,

2