111

The Learning Curve for Laparoscopic Common Bile Duct Exploration through a Choledochotomy

- Report on 50 Patients

Department of Surgery, Daedong Hospital, Busan, Korea

Kyung Min Hong, M.D., Byung Doe Chai, M.D., Dong Beom Seo, M.D., Ki Beom Ku, M.D., Kyung Whan Park, M.D.

Purpose: Since the indications for laparoscopic surgery have been broadened to encompass many abdominal surgeries, there have been many studies that have quantified the learning curve for each surgical procedure. This article is designed to estimate the learning curve for laparoscopic common bile duct exploration (LCBDE), as there are currently few reports on this.

Methods: Fifty consecutive laparoscopic common bile duct explorations through a choledochotomy were performed by one experienced laparoscopic surgeon who had carried out 283 laparoscopic cholecystectomies, and we retrospectively analyzed the data for the operative time, the number of long (≥ 180 minutes) and short (≤ 120 minutes) operations, the conversion rate, the ductal clearance rate and the complication rate. The relations between stone extraction methods and operative time were also analyzed.

Results: After 25 cases of laparoscopic common bile duct exploration, the mean operative time was significantly decreased from 177.6 to 136.6 minutes with a decrease in

the number of long operations from 10 to 2 and there was an increase in the number of short ones from 1 to 12 (p < 0.05). The conversion rate, ductal clearance rate and complication rate were 10%, 91% and 11%, respectively, with no statistically significant change. Performing electrohydraulic lithotripsy (EHL) and extracting impacted stones were still the time-consuming procedures even if the surgeon had experienced as many as 25 LCBDEs.

Conclusion: A laparoscopic surgeon who is proficient in laparoscopic cholecystectomy can reach the late phase of experience in performing LCBDE after the early phase of experiencing 25 cases of LCBDEs.

Key words: Laparoscopic common bile duct exploration, Learning curve, Common bile duct stones, Laparoscopic choledochotomy, LCBDE

중심단어: 복강경 총수담관 탐색술, 학습 곡선, 총수담관 결석, 복강경 담관절개술, LCBDE

Correspondence address: Kyung Whan Park, MD, Department of Surgery, Daedong Hospital, 530-1, Myeongnyun 1-dong, Dongnae-gu, Busan 607-711, Korea; Tel 82-51-554-1233 Fax 81-51-553-7575;

E-mail: dd59@kornet.net

※ 통신저자:박경환, 부산시 동래구 명륜1동 530-1 우편번호:607-711

대동병원 외과

Tel:051-554-1233, Fax:051-553-7575 E-mail:dd59@kornet.net

INTRODUCTION

Since laparoscopic surgery has been introduced in 1950s, it has been taking over conventional surgery in many surgical fields with technical developments and its advantages in relation to less invasiveness, less complications and shorter hospital stay. Learning curves for laparoscopic surgeries have been studied over years because they demand techniques to learn and some experiences not to make serious complications.

1-3The learning curve of any procedure is a repetition of that task until it is learned. It consists of an early

phase of experience in which the ability to complete the procedure successfully increases rapidly. This steep rise then changes slowly in the late phase of experience, whereby the improvement in performance becomes more modest until the curve becomes flat without any further detectable change in the plateau phase of experience.

4Since the first laparoscopic cholecystectomy has been reported in 1989, it has taken its place as a standard treatment for benign gallbladder diseases and been performed in many centers around the world with its easiness to learn even though it has a risk of serious complications.

5-7In contrast, even if laparoscopic common bile duct exploration (LCBDE) for the treatment of common bile duct (CBD) stones has been proved to be safe and feasible

8in comparison to preoperative endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) with laparoscopic cholecystectomy (LC),

9-12intraoperative endoscopic sphincterotomy with LC,

13,14and postoperative ERCP with LC,

15,16there are not so many centers practicing LCBDE for its technical difficulty.

There have been few studies on the learning curve for

LCBDE until now because 1) the speed of learning LCBDE which has technical difficulties to overcome could be variable depending on the experience of laparoscopic cholecystectomy, and 2) there are few reports on the plateau phase of the learning curve for laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Voitk AJ, et al.

17reported on the learning curve for laparoscopic cholecystectomy that the plateau phase was achieved after the first 20 cases of the early phase of experience and another 200 consecutive elective operations of the late phase of experience. Therefore, this study is designed to define the learning curve for LCBDE of one experienced laparoscopic surgeon who had performed more than 220 laparoscopic cholecystectomies.

METHODS

1) Patients

Fifty consecutive ‘LC and LCBDE’s from 2000 to 2007 performed by one experienced laparoscopic surgeon who had carried out LC from 1991 in a 300-bed teaching general hospital were studied retrospectively. There were no patients who had previously undergone cholecystectomy or CBD exploration, whether open or laparoscopic. The surgeon had performed 283 cases of laparoscopic cholecystectomies before the study started and the mean operative time of the last 30 operations was 66 minutes.

Fifty cases of ‘LC and LCBDE’s were divided into two groups of 25 consecutive cases: Group 1 consists of the first 25 cases and Group 2 the next 25 cases. The variables studied were as follows: operative time (mean, range, standard deviation, number of operations not less than 180 and not more than 120 minutes), methods of CBD stone extraction, preoperative ERCP trial, postoperative hospital stay, conversion rate and complication rate, etc. Observed differences were subjected to statistical analysis using Mann-Whitney test or Fisher’s exact test as nonparametric tests; a difference was considered significant if p-value was less than 0.05.

The diagnosis of CBD stones was based on clinical presentations, liver function tests, ultrasonography and computed tomography. Additional magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) was taken if there was any suspicion of CBD stones. In general, ERCP was preferred in patients with acute cholangitis or severe gallstone pancreatitis.

For patients with large stones (> 1 cm), multiple stones, or stones located in the common hepatic duct and intrahepatic duct, LCBDE was performed. Failure of endoscopic sphincterotomy and stone extraction also led to perform LCBDE.

2) Operative procedures

Surgery was performed under general anesthesia with the patient in reverse Trendelenburg position. A four-port technique was employed: a 12 mm umbilical port for a 30-degree laparoscope; a 10 mm subxiphoid port for a dissector and a 5 mm choledochoscope (Olympus CHF 20Q, Olympus Corp, Tokyo, Japan); a 5 mm right subcostal port; a 5 mm right flank port in the anterior axillary line. The cyst duct was dissected down to the CBD, and clamped or ligated to prevent GB stones from passing into the CBD during LCBDE. One to 2 cm long choledochotomy was made on the anterior wall of CBD using endoscopic scissors. Stone extraction was performed using various methods, i.e. saline flushing, laparoscopic dissector, Fogarty balloon catheter (3∼6 Fr latex free Arterial Embolectomy Catheter, Syntel Inc, Laguna Hills, Calif, USA), stone retrieval basket (4-Wire 4.5 Fr Segura Hemisphere Stone Retrieval Basket, Microvasive Boston Scientific Corp, Watertown, MA, USA; 5-Wire 4.0 Fr Highflex Stone Basket, Angiomed, Karlsruhe, Germany) through a choledochoscope, and EHL (Karl Storz Calcutript Electrohydraulic Lithotriptor, Karl Storz, Tuttlingen, Germany). With regard to choosing stone extraction methods, the surgeon preferred using a dissector for visible stones which were right under a choledochotomy, saline flushing for small stones, and a basket or Fogarty catheter for stones located away from a choledochotomy. EHL was used in case of impacted or large stones. A T-tube was placed for the decompression of CBD, postoperative cholangiography, and percutaneous choledocho- scopic removal of CBD stones if they were found on postoperative cholangiography. If there were an endoscopic nasobiliary drainage (ENBD) placed preoperatively and no possibility of remnant stones, primary closure was preferred with the ENBD in situ without a T-tube placement. Selective operative cholangiography was performed on the preoperative suspicion of CBD stones via cystic duct or via an ENBD if there was, and on any doubt of complete extraction of CBD stones via an ENBD or a T-tube. Endeavoring intracorporeal closure of the choledochotomy was performed using 3-0 Vicryl continuous suture. On the completion of LCBDE, laparoscopic cholecystectomy was made in the routine manner.

3) Postoperative managements

A postoperative cholangiography was routinely performed

via a T-tube or an ENBD. The ENBD was removed during

admission. The T-tube which had been clamped on discharge

was removed on an outpatient basis by the results of

Table 1. Patient characteristics

Group 1 Group 2 Total p value

Male/Female Mean age (years) Age ≥ 70 Comorbid disease

Previous upper abdominal surgery Infection on admission

Serum total bilirubin > 3 mg/dl

11/14 64 7 (28%) 9 (36%)

0 12 (48%) 5 (20%)

11/14 70 14 (56%) 12 (48%)

0 14 (56%) 11 (44%)

22/28 67 21 (42%) 21 (42%)

0 26 (52%) 16 (32%)

1.000 0.046 0.085 0.567 1.000 0.778 0.128

Table 2. Preoperative and operative findings

Group 1 Group 2 Total p value

Preoperative ERCP ENBD status

Spontaneous passage of stones Stricture of ampulla of Vater

Maximal diameter of CBD (mean, mm) Maximal size of CBD stones (mean, mm)*

Number of CBD stones (mean, n)*

Impacted CBD stones Presence of IHD stones Moderate or severe adhesion

17 (68%) 12 (48%) 1 (4%) 1 (4%) 16.2 14.7 2.4 5 (20%)

2 (8%) 8 (32%)

15 (60%) 6 (24%) 1 (4%)

0 15.5 12.8 2.5 4 (16%)

0 6 (24%)

32 (64%) 18 (36%) 2 (4%) 1 (2%) 15.9 13.7 2.5 9 (18%)

2 (4%) 14 (28%)

0.769 0.140 1.000 1.000 0.661 0.831 0.755 1.000 0.490 0.754

ERCP = endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography; ENBD = endoscopic nasobiliary drainage; CBD = common bile duct; IHD = intrahepatic duct; *Three cases (2 spontaneous passages, 1 stricture) are excluded.

cholangiography. If there were any remnant stones on the cholangiography, percutaneous choledochoscopic choledocho- lithotomies via the T-tube tract were performed repeatedly until there were no more remnant stones, which were done in the outpatient department under local anesthesia 4 weeks after LCBDE.

RESULTS

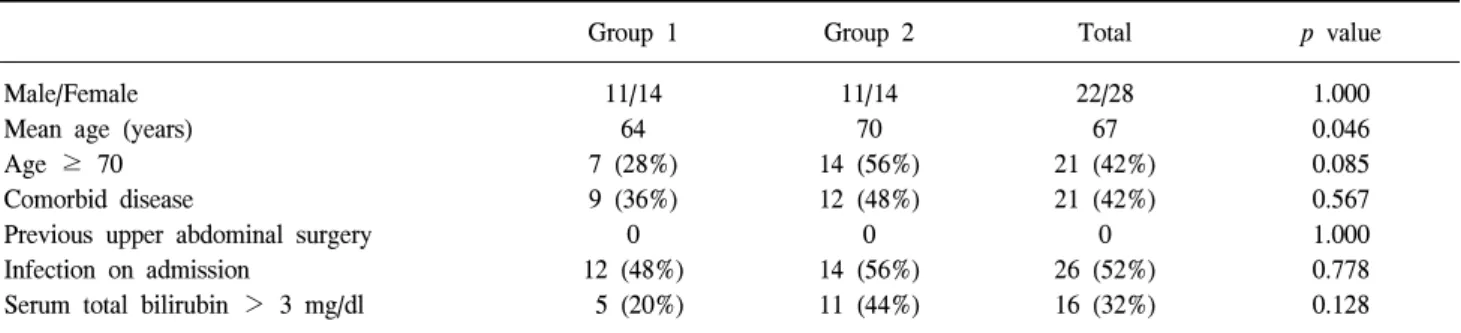

1) Patients characteristics

Average age for the 50 patients was 67 years; 28 (56%) were females; 21 (42%) patients had comorbid diseases (diabetes mellitus, hypertension, cerebral vascular accident, etc.); 26 (52%) patients had acute cholecystitis or cholangitis on admission; and 16 (32%) patients had a serum total bilirubin level over 3 mg/dl. There were no patients having upper abdominal surgery previously. Group 2 were significantly older than Group 1 (p < 0.05). Otherwise, there were no statistically significant differences between Group 1 and Group 2 (Table 1).

2) Preoperative and operative findings

In 32 (64%) of 50 patients, preoperative endoscopic sphincterotomy was tried but failed, and of which 18 (36%) patients had an ENBD as a result. Two cases were diagnosed intraoperatively as spontaneous passage of CBD stones and one case postoperatively as stricture of ampulla of Vater. Maximal diameter of CBD was 15.9 ± 4.8 mm in average ± SD (standard deviation). Maximal size and the number of CBD stones were 13.7 ± 6.8 mm and 2.5 ± 2.0 in average ± SD, respectively. Nine (18%) patients had impacted CBD stones and 2 (4%) patients had intrahepatic duct (IHD) stones combined with CBD stones. There was moderate or severe adhesion in 14 (28%) patients. No statistically significant difference was found between Group 1 and 2 in each variable above (Table 2).

3) Operative procedures and results of the operation

There were 5 (10%) cases converted to open surgery with

no significant difference between the two groups (two for

Table 3. Operative procedures and results

Group 1 (23)* Group 2 (22)* Total (45)* p value Operative procedures

Operative cholangiography T-tube drainage

Primary closure

Choledochoduodenostomy Results of the operation

Operative time (mean ± SD, min) Range (min)

No. ≥ 180 minutes No. ≤ 120 minutes Complete extraction

Postoperative hospital stay (mean ± SD, days) Complication rate

Postoperative procedures First follow-up cholangiograpy via T-tube, ENBD (n) POD of cholangiography (mean) POD of ENBD removal (mean) POD of T-tube removal (mean) Additional operation

8 (34.8%) 17 (73.9%) 5 (21.7%) 1 (4.3%)

177.6 ± 42.4 120∼250 10 (43.5%)

1 (4.3%) 21 (91.3%)

9.0 ± 3.0 2 (8.7%)

20

6.7 5.0 23.4 2 (8.7%)

3 (13.6%) 17 (77.3%) 5 (22.7%)

0

136.6 ± 51.1 100∼330 2 (9.1%) 12 (54.5%) 20 (90.9%) 10.5 ± 3.5 3 (13.6%)

22

7.3 8.0 21.4 2 (9.1%)

11 (24.4%) 34 (75.6%) 10 (22.2%) 1 (2.2%)

157.6 ± 50.7 100∼330 12 (26.7%) 13 (28.9%) 41 (91.1%) 9.7 ± 3.3 5 (11.1%)

42

7.0 6.7 22.4 4 (8.9%)

0.165 1.000 1.000 1.000

0.000

0.017 0.000 1.000 0.176 0.665

0.233

0.177 0.056 0.804 1.000 SD = standard deviation; ENBD = endoscopic nasobiliary drainage; POD = postoperative day; *Patients numbers excluding 5 cases converted to open surgery

Group 1 and three for Group 2). In Group 1, an impacted distal CBD stone was the reason for the open conversion in one patient, and failure to remove the basket wire which was fractured during ERCP in the other patient. Severe adhesion, profound bleeding from GB bed after completing LCBDE, and impacted CBD stones were the reasons for the open conversion in 3 patients in Group 2, respectively.

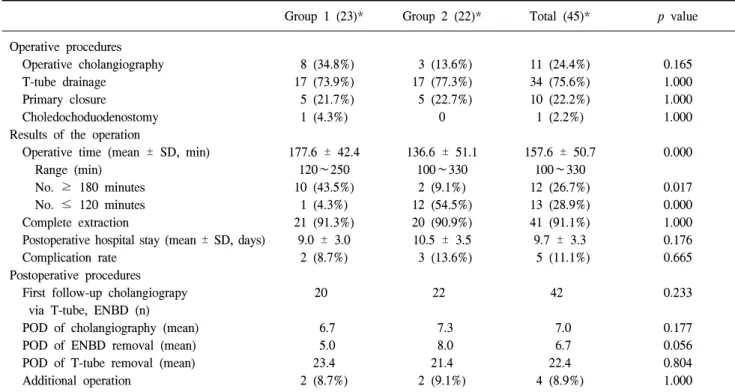

Of 45 patients excluding the 5 converted cases, all had choledochotomy, and of which 34 (76%) patients had a T-tube inserted, 10 (22%) patients had primary closure, and the last one (2%) had choledochoduodenostomy (Table 3). Nine patients out of the 10 patients who had primary closure had an ENBD left in situ, and only the remaining one patient had primary closure without an ENBD. Intraoperative cholangio- graphy was done in 11 (24%) patients: via cystic duct in 5, via an ENBD in 5 and via a T-tube in one patient.

The Table 3 also lists operative time, postoperative hospital stay, complete extraction rate, etc. in Group 1 and 2 which exclude the 5 converted cases. The mean operative time for Group 2 was 136.6 minutes compared to 177.6 minutes for Group 1 with statistically significant difference (p < 0.05). The operative time contracted with a significant decrease in the number of long operations (from 10 to 2, p < 0.05) and a

significant increase in the number of short ones (from 1 to 12, p < 0.05). Complete stone extraction was achieved in 41 (91%) patients with no significant difference between the two groups. In the remaining 4 patients, remnant stones were completely removed by percutaneous choledochoscopic choledocholithotomy via a T-tube tract on an outpatient basis 4 weeks after LCBDE.

The first follow-up cholangiography was performed in 42 among 45 patients on the postoperative day 4 to 11 (mean 7.0).

The ENBD was removed on the postoperative day 4 to 13 (mean 6.7). The T-tube was removed on the postoperative day 8 to 38 (mean 22.4): in the shortest one it was slipped out spontaneously and in the longest one it was removed after complete extraction of remnant stones. There were no statistically significant differences in those variables between Group 1 and 2.

The mean postoperative hospital stay was 9.7 days ranging

from 4 to 19 days with no significant difference between the

two groups. There were 5 (11%) patients who had postoperative

complications with no significant difference between the two

groups (two in Group 1, three in Group 2). In Group 1, one

patient had cholangitis and urinary tract infection, and the other

patient had cholangitis and acute renal failure due to remnant

Table 5. The relations between stone extraction methods and operative time*

The relation between using saline flushing only and operative time p-value

Number of patients Mean operative time

non-SFO 30 170.7 ± 54.6

SFO 12 127.9 ± 30.0

Total 42

158.5 ± 52.3 0.008

Comparison of operative time of Group 1 and 2 in patients of SFO group

SFO

Mean operative time

Group 1 4 161.3 ± 28.7

Group 2 8 111.3 ± 10.6

Total 12

127.9 ± 30.0 0.008

The relation between using a laparoscopic dissector and operative time p-value

Number of patients Mean operative time

non-Dissector 34 165.6 ± 55.0

Dissector 8 128.1 ± 20.9

Total 42

158.5 ± 52.3 0.091

Comparison of operative time of Group 1 and 2 in patients of Dissector group

Dissector

Mean operative time

Group 1 3 130.0 ± 10.0

Group 2 5 127.0 ± 26.6

Total 8

128.1 ± 20.9 0.732

The relation between using a stone retrieval basket and operative time p-value

Number of patients Mean operative time

non-Basket 33 156.4 ± 53.8

Basket 9 166.1 ± 48.5

Total 42

158.5 ± 52.3 0.454

Comparison of operative time of Group 1 and 2 in patients of Basket group

Basket

Mean operative time

Group 1 6 190.0 ± 41.1

Group 2 3 118.3 ± 7.6

Total 9

166.1 ± 48.5 0.024

The relation between using EHL and operative time p-value

Number of patients Mean operative time

non-EHL 30 138.8 ± 37.9

EHL 12 207.5 ± 52.2

Total 42

158.5 ± 52.3 0.000

Comparison of operative time of Group 1 and 2 in patients of EHL group

EHL

Mean operative time

Group 1 8 204.4 ± 38.6

Group 2 4 213.8 ± 80.4

Total 12

207.5 ± 52.2 0.937

SFO = saline flushing only; EHL = electrohydraulic lithotripsy; Mean operative time is expressed in minutes ± standard deviation.

*Converted cases (5) and cases without CBD stones (3) are excluded.

Table 4. Stone extraction methods

Stone extraction methods Group 1* Group 2* Total*

Saline flushing only Laparoscopic dissector Stone retrieval basket

Electrohydraulic lithotripsy (EHL) EHL and stone retrieval basket Fogarty balloon catheter

4 (19.0) 3 (14.3) 6 (28.6) 7 (33.3) 1 (4.8)

0

8 (38.1) 5 (23.8) 3 (14.3) 3 (14.3) 1 (4.8) 1 (4.8)

12 (28.6) 8 (19.0) 9 (21.4) 10 (23.8) 2 (4.8) 1 (2.4)

Total 21 21 42

Fisher’s exact test, p-value = 0.347; *Which excluding 5 cases converted and 3 cases without CBD stones;

†Values in parentheses are percent.

stones. In Group 2, one patient had acute renal failure and cerebellar infarction with immediate recovery who was discharged on the 19

thpostoperative day, another patient had wound seroma, and the other patient had Candida esophagitis and acute renal failure owing to contrast leakage during T-tube cholangiography who was discharged on the 18

thpostoperative day. There was no mortality in all patients.

4) The relations between stone extraction methods and operative time

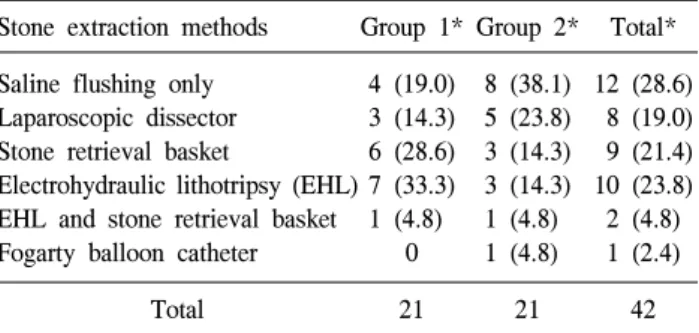

Table 4 lists stone extraction methods for the two groups

excluding 5 cases converted and 3 cases without CBD stones.

Table 6. The relations between stone extraction methods and operative time*

Not-impacted CBD stones Impacted CBD stones Total p-value

Number of patients Mean operative time

35 149.6 ± 42.3

7 202.9 ± 76.1

42

158.5 ± 52.3 0.083

Comparison of operative time of Group 1 and 2 in patients without impacted CBD stones

Not-impacted CBD stones Mean operative time

Group 1 17 177.9 ± 41.0

Group 2 18 122.8 ± 20.8

Total 35

149.6 ± 42.3 0.000

Comparison of operative time of Group 1 and 2 in patients with impacted CBD stones

Impacted CBD stones Mean operative time

Group 1 4 196.3 ± 51.1

Group 2 3 211.7 ± 115.1

Total 7

202.9 ± 76.1 1.000

CBD = common bile duct; Mean operative time is expressed in minutes ± standard deviation. *Converted cases (5) and cases without CBD stones (3) are excluded.

Saline flushing was enough to extract stones in 12 patients.

Otherwise, they were extracted using laparoscopic dissector in 8 patients; stone retrieval basket in 9 patients; EHL in 10 patients; EHL and stone retrieval basket in 2 patients; Fogarty balloon catheter in one patient. There was no statistically significant difference in stone extraction methods between the two groups (p = 0.347).

Stone extraction methods or impacted stones themselves may influence on the operative time. The authors tried to find out some correlations among them. Table 5 shows the relations between each stone extraction method that was used and operative time. In the comparison of the non-saline-flushing- only (non-SFO) group and the saline-flushing-only (SFO) group, the SFO group had significantly shorter operative time than the non-SFO group as easily expected (127.9 min vs.

170.7 min, p < 0.05). Group 2 had shorter operative time than Group 1 in the SFO group (111.3 min vs. 161.3 min, p < 0.05).

These may lead to an impression that there is a skill improvement in extracting CBD stones with saline flushing.

In the comparison of the non-Dissector group and the Dissector group, the Dissector group had shorter operative time than the non-Dissector group with a borderline significance (128.1 min vs. 165.6 min, p = 0.091). In the Dissector group there was no statistically significant difference in operative time between Group 2 and 1 (127.0 min vs. 130.0 min). CBD stones can be easily extracted using a dissector as the result verified.

In the comparison of the non-Basket group and the Basket group, there was no significant difference in operative time (156.4 min vs. 166.1 min). Group 2 had shorter operative time than Group 1 in the Basket group (118.3 min vs. 190.0 min,

p < 0.05). With the results, one can conclude that even if using a stone retrieval basket is a difficult procedure, a surgeon can make a significant improvement in the skills of manipulating a stone retrieval basket when he/she experiences as many as 25 LCBDEs.

In the comparison of the non-EHL group and the EHL group, the EHL group had significantly longer operative time than the non-EHL group, showing that EHL was a time-consuming procedure (207.5 min vs. 138.8 min, p < 0.05). In the patients whose CBD stones were extracted by EHL, Group 2 and 1 did not show any significant difference in the operative time (213.8 min vs. 204.4 min), which means EHL procedure is still one of the time-consuming procedures even if a surgeon has experienced enough to perform LCBDE.

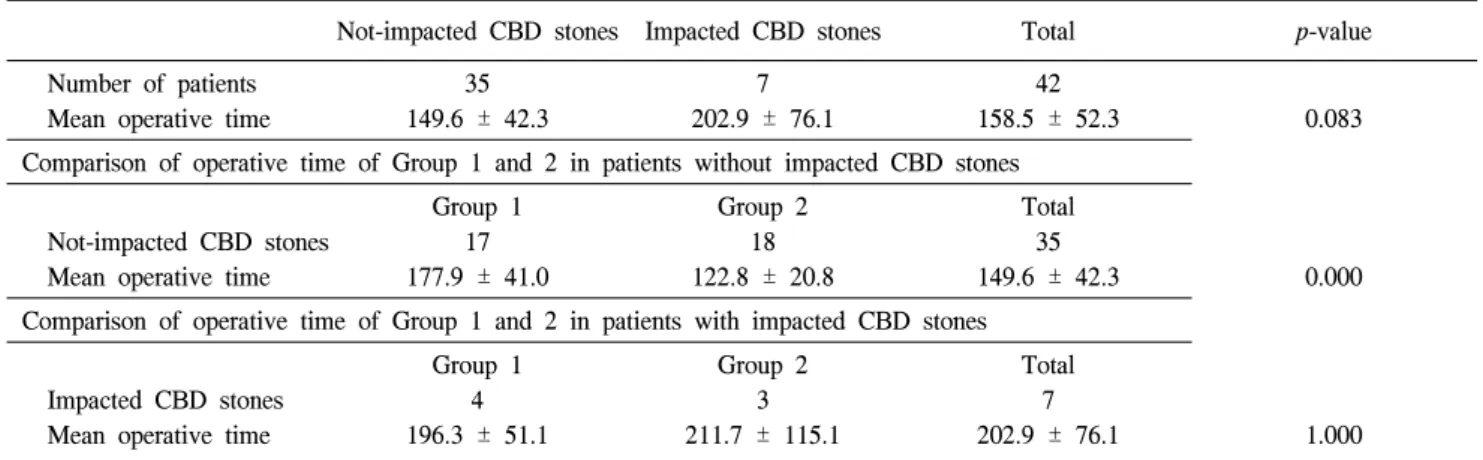

Since the surgeon usually had chosen to perform EHL for impacted stones, impacted CBD stones themselves could be a time-consuming factor. The authors tried to analyze the relations among impacted CBD stones and operative time.

Table 6 shows the relation between impacted CBD stones and operative time. In the comparison of the not-impacted-CBD- stones group and the impacted-CBD-stones group, the latter had longer operative time than the former with a borderline significance (202.9 min vs. 149.6 min, p = 0.083). In the patients without impacted CBD stones, Group 2 had much less operative time than Group 1 (122.8 min vs. 177.9 min, p < 0.05).

In the patients with impacted CBD stones, both Group 2 and

1 have long operative time (211.7 min vs. 196.3 min), which

means extracting impacted CBD stones is a difficult work even

if a surgeon has experienced enough to perform LCBDEs.

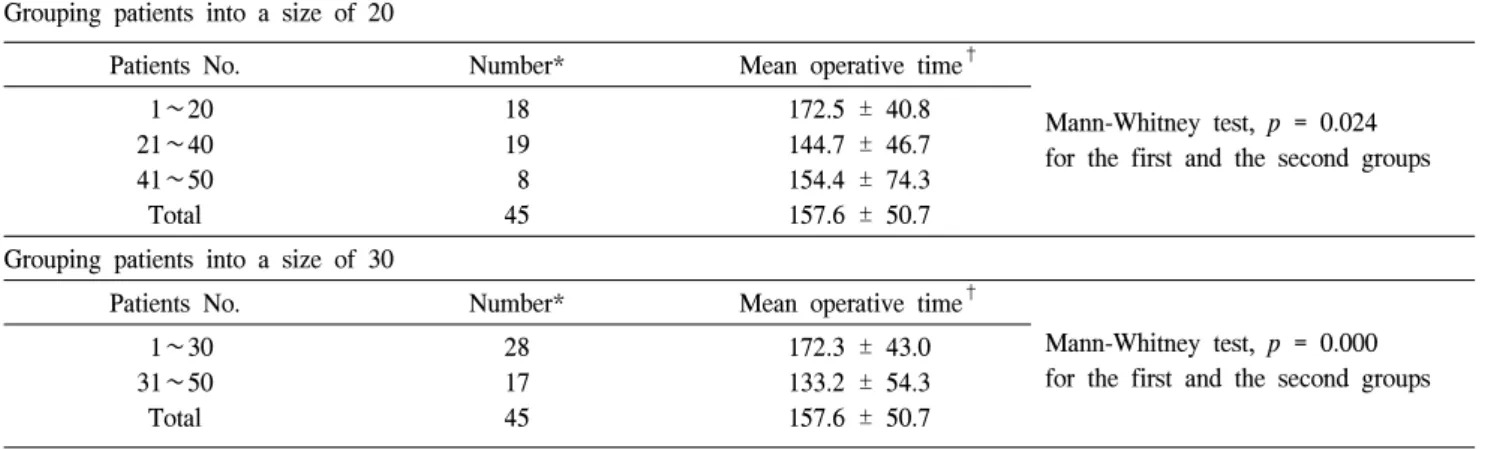

Table 7. Grouping patients into a different size Grouping patients into a size of 20

Patients No. Number* Mean operative time

†Mann-Whitney test, p = 0.024 for the first and the second groups 1∼20

21∼40 41∼50 Total

18 19 8 45

172.5 ± 40.8 144.7 ± 46.7 154.4 ± 74.3 157.6 ± 50.7 Grouping patients into a size of 30

Patients No. Number* Mean operative time

†Mann-Whitney test, p = 0.000 for the first and the second groups 1∼30

31∼50 Total

28 17 45

172.3 ± 43.0 133.2 ± 54.3 157.6 ± 50.7

*Number of cases excluding converted ones;

†Mean operative time is expressed in minutes ± standard deviation.

DISCUSSION

There are many studies reporting LCBDE is a safe and feasible

8procedure in dealing with CBD stones, comparing to preoperative ERCP with LC,

9-12intraoperative endoscopic sphincterotomy with LC,

13,14and postoperative ERCP with LC,

15,16etc. LCBDE can be performed in different ways with their advantages and disadvantages: transcystic common bile duct exploration;

18,19laparoscopic choledochotomy;

20,21laparo- scopic antegrade sphincterotomy.

22,23In the series of studies, the mean operative time ranges from 48 to 240 minutes, conversion rate from 0 to 17 percent and ductal clearance rate from 80 to 100 percent. In this study, after the first 25 trials of laparoscopic choledochotomy the mean operative time was 136.6 minutes, conversion rate was 12 percent, and complete ductal clearance rate was 91 percent.

1) Study design

There have been few studies that document the learning curve for LCBDE. To the authors’ knowledge, the only report about the learning curve for LCBDE was made in 1999 by Keeling NJ, et al.

24In the study, 120 consecutive LCBDEs were divided into two groups with a size of 60. The second group had significantly shorter operative time and better complete extraction rate than the first group (130 min vs. 150 min, 97% vs. 81%, respectively, p < 0.05). But, they did not try to define the learning curve for LCBDE. We assume the reasons for that are 1) LCBDE can be performed in different ways, e.g. transcystic approach and laparoscopic choledochotomy, 2) laparoscopic surgeons rarely start to perform LCBDE with few experiences of LC, but only when he/she is proficient in

LC, and 3) there is no consensus for who is fully proficient in LC. Voitk AJ, et al.

17reported in their study on the learning curve for laparoscopic cholecystectomy that the plateau phase was achieved after the first 20 cases of the early phase of experience and another 200 consecutive elective operations of the late phase of experience. Therefore, the authors decided to identify the learning curve for LCBDE only through a choledochotomy performed by one experienced laparoscopic surgeon, based on that study.

For the purpose of this study, it is appropriate to study the learning curve of LCBDE when a laparoscopic surgeon starts to perform LCBDE after he/she is fully proficient in LC. But, most surgeons start to carry out LCBDE during his/her late phase of experience in performing LC. The surgeon in this study started to perform LC in 1991. He began to perform LCBDE in 1992 with prior experience of 3 laparoscopic cholecystectomies. With a frequency of 1∼2 cases per year, by 1999 he had performed 7 cases of LCBDEs in total. And in view of the fact that the last LCBDE before the start of this study in August 2000 was done in 1998, the previous experience of LCBDE did not seem to have much effect on the study of the learning curve.

There is another limitation of the study which is not

amendable. The number ‘220’ is not the exact cut-off value for

every laparoscopic surgeon to reach the plateau phase of the

learning curve for LC. To verify if the surgeon is fully

proficient in LC, the authors should have analyzed his own

cut-off value for the plateau phase. Unfortunately, though,

because of no medical records available before 1999, there is

no way to prove that the surgeon was fully proficient in LC

before the start of the study. The surgeon, however, had

performed total of 283 cases of LC before the study, which is

much more than 220, with a mean operative time of 66 minutes for the last 30 cases. The authors assume that the surgeon was fully experienced in LC, according to the report of Voitk AJ, et al.

17Therefore, it seems to be appropriate to study the learning curve for LCBDE on the 50 consecutive cases from August 2000.

The authors have divided the cases into 10, 15, 20, 25 and 30 cases and analyzed the difference of operation time (Table 7).

Since the 50 cases were grouped in the size of 20 cases, there was a significant difference in operative time between the first and the second groups (172.5 min vs. 144.7 min, p < 0.05), but the third group still had a long operative time (154.4 min) implying as if there might not be further improvement after 20 LCBDEs. In this reason, the authors decided not to group the cases in the size of 20. They again were grouped in the size of 30 and it also showed a significant difference in operative time between the first and the second groups (172.3 min vs.

133.2 min, p < 0.05). But it was enough to group them into the size of 25 to make the surgeon seem proficient in LCBDE.

Supporting that, there were a significant decrease in the number of long operations and a significant increase in the number of short ones. The authors, however, could not find any significant differences in conversion rate, complication rate, complete extraction rate and postoperative hospital stay.

2) Improvement in the skills of stone extraction and dealing with impacted stones

In the analysis of stone extraction methods and operative time (Table 5), the authors have found there could be skill improvement in performing saline flushing and using a basket via a choledochoscope. There, however, might be other operative skills or any other factors affecting the operative time, such as improvement of skills in manipulating a choledochoscope and closing of a choledochotomy. In spite of lack of records on these confounders, the surgeon felt to have become more proficient in extracting stones with saline flushing and a basket via a choledochoscope, even in manipulating a choledochoscope and closing of a choledochotomy. To have a statistical significance, all those factors should have been analyzed altogether in a larger study size. CBD stones can be easily extracted using a dissector. In this study the size of the Dissector group was too small for statistical analysis to confirm possible improvement in other skills that might have been shown in Group 2.

A common definition of an impacted stone is a stone preventing a wire, a basket or a catheter from passing beyond itself in the beginning. After several attempts with saline

flushing, baskets or catheters, surgeons usually choose to use laser, ultrasonic, or electrohydraulic lithotripsy to extract the impacted CBD stone.

25,26In this study only EHL was used in 6 out of 7 patients with impacted stones, with a mean operative time of 220 minutes. EHL also was used in 6 out of 35 patients without impacted stones, with a mean operative time of 195 minutes. And the surgeon did not make a significant skill improvement in performing EHL as shown in Table 5.

Therefore, the authors believe that using EHL and extracting impacted CBD stones are laborious tasks even for an experienced surgeon.

CONCLUSIONS

This study demonstrates that a laparoscopic surgeon who is fully proficient in laparoscopic cholecystectomy can reach the late phase of the learning curve for LCBDE through a choledochotomy after the early phase of experiencing 25 LCBDEs. Performing EHL and extracting impacted stones are still the time-consuming procedures even if a surgeon has experienced many LCBDEs. Operative skills can be improved in performing some procedures, such as saline flushing, using a basket via a choledochoscope, manipulating a choledocho- scope and closing of a choledochotomy, etc.

There can be some statistical errors because this is a small and retrospective study. The authors propose a prospective cohort study with a larger size, which can define the early, late and plateau phase of the learning curve for LCBDE, and which also can explain the relations between stone extraction methods and operative time for a statistical significance.

REFERENCES