Korean J Androl. Vol. 29, No. 1, April 2011

53

접수일자: 2011년 3월 22일, 수정일자: 2011년 4월 12일, 게재일자: 2011년 4월 14일

Correspondence to: Sung Won Lee

Department of Urology, Samsung Medical Center, 50, Ilwon-dong, Kangnam-gu, Seoul 135-710, Korea Tel: 02-3410-3552, Fax: 02-3410-3027

E-mail: drswlee@skku.edu

Medical Profession's Awareness and Attitude Toward the Sexuality of Cancer Patients in South Korea

Jun Ho Lee1, Deok Hyun Han1, Tai Young Ahn2, Sung Ho Ju1, Byung Kuk So1, Sung Won Lee1 Department of Urology, 1Samsung Medical Center, Sungkyunkwan University College of Medicine,

2Asan Medical Center, University of Ulsan College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea

= Abstract =

Purpose: To investigate the practice and attitude of healthcare professionals toward the sexuality of cancer patients.

Materials and Methods: The subjects were comprised of doctors and nurses who served at two medical centers.

Questionnaires consisted of five domains and fourteen questions were disseminated via emails in March 2009. The first domain (3 questions) pertained the recognition of sexual dysfunction in cancer patients, the second (2 questions) pertained cancer patients’ experience of sexual dysfunction, the third (3 questions) pertained the attitude to cancer patients with sexual dysfunction, the fourth (3 questions) pertained capacity for sexual dysfunction treatment, and the fifth (3 questions) pertained problems or difficulties encountered when facing cancer patients’ sexual dysfunction.

Results: Three hundred and twenty-six men and women completed the questionnaires, giving a response rate of 85.4%. The mean age was 33.6 years. The proportion of doctors and nurses were respectively 48.2% and 51.8%.

The proportion of males and females were 29.8%, and 70.2%, respectively. Ninety point five per cent (90.5%) of respondents answered that cancer patients’ sexual dysfunction is important to quality of life. However, fewer medical professionals (27.4%) give an affirmative answer that patients requested sexual dysfunction therapy. The occurred particularly less frequently in physicians (13.2%) than in surgeons (55.6%). Fifty-four point six (54.6%) percent of respondents said that they tried to resolve the problem when patients asking for treatment of sexual dysfunction. Only 38.3% of respondents experienced little or no difficulty in behaving naturally when counseling cancer patients about their sexual dysfunction. Female doctors and nurses more often experience embarrassment when addressing sexuality with patients. In addition, most respondents (84.0%) felt that theoretical knowledge on cancer patients’ problems is needed.

Conclusions: Most healthcare professionals agreed that sexual problems of cancer patients were important for quality of life. However, they frequently felt a lack of communicating skills and theoretical knowledge. Education programs on this issue and an appropriate contact system with specialists should be established.

Key Words: Erectil dysfunction, Cancer, Knowledge, Attitudes, Behaviors

Introduction

Cancer is a rapidly increasing disease and the sec-

ond largest cause of death in South Korea.1 Many can- cer patients might undergo surgery and they could also require neo-adjuvant or adjuvant therapy in the form of chemotherapy or radiotherapy, depending on their histology and the location of the cancer. These treat- ment and cancer itself could impact seriously on the physical and mental quality of life (QoL). For exam- ple, erectile dysfunction, alteration of body image, bowel habit change, and depression. One thing in par- ticular to note is sexual problem, because sexuality is

being increasingly regarded as an important compo- nent in the QoL cancer patients.2

In addition, the incidence of sexual problems is high in cancer patients. Among prostate cancer patients who were preoperatively potent and whose postoperative erectile function was assessed without erectile dys- function therapy, the incidence of erectile dysfunction over varying periods of time ranged from 24% to 82%.3-8 In bladder cancer, sexual inactivity following surgery increased from 20% before cystectomy to 50% at fol- low-up. Preoperatively, 35% experienced erectile dys- function, compared to 94% at follow-up.9 In a retro- spective survey of 476 colorectal cancer survivors who had lived a mean of 10 years with colostomy, com- plaints about interference with sex were common.

Fifteen percent (15%) of these cancer survivors had become sexually inactive. Erectile dysfunction was present in 79% of men.10 In gynecological cancer, re- cent studies demonstrated that between 30% and 63%

of women who underwent treatment for cervical can- cer experienced some sexual difficulties. The majority of women (62∼88%) are at high risk for developing vaginal agglutination, stenosis within the first 3 months of radiotherapy.11 Sexual complaints after the diagnosis of breast cancer, occurring alone or in com- bination, are relatively common; including all sexual complaints 30∼100%, desire disorder 23∼64%, arousal or lubrication concerns 20∼48%, orgasmic concerns 16∼36%, and dyspareunia 35∼38%.12-15

Because of its incidence and impact on QoL, cancer patients’ sexual concerns have been identified as an essential aspect of care, given the great number of rel- evant research studies conducted worldwide in recent years.16-19 Medical professionals need to possess deep knowledge and exercise sound judgment and high lev- el of sensitivity in dealing with patients’ sexual health needs.

Considering the incidence of sexual problems, an important component in the patients’ overall QoL, and the role the medical professional plays in managing sexual problem, it is important to study the awareness and attitude of the medical profession on the patients’

sexual problem. In this study, we investigated the practice of healthcare professionals at the Samsung

medical center (Seoul, Korea) and the Asan medical center (Seoul, Korea). To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study that systemically examines this issue in the Republic of Korea.

Materials and Methods

The subjects of this study included doctors and nurses practiced at two medical centers (Samsung medical center and Asan medical center, Seoul, Korea). The subjects were limited to medical professionals in con- tact with cancer patients.

For this study, questionnaires consisted of five do- mains and fourteen questions were developed. The first domain pertained the recognition of sexual dys- function in cancer patients by healthcare professionals.

This domain was consisted of 3 questions: “I know that cancer patients may experience the sexual dys- function”; “I think that the cancer patients’ sexual dysfunction is important to QoL”, and “I think that lis- tening to their sexual problem is important”.

The second domain is about the experience of fac- ing cancer patients’ sexual dysfunction. This domain was consisted of 2 questions: “I have encountered cancer patients’ sexual dysfunction during medical ac- tivities”, and “I have experienced patients asking for sexual dysfunction therapy”.

The third domain pertained the attitude to cancer pa- tients who may suffer from sexual dysfunction. This domain was consisted of 3 questions: “I have a pos- itive manner about cancer patients’ sexual dysfunc- tion”, “If cancer patients ask for their sexual dysfunc- tion treatment, I try to resolve the problem”, and

“When the cancer patients complain of sexual dysfunc- tion, I refer to a specialist”.

The fourth domain pertained the capacity for sexual dysfunction treatment. This domain was consisted of 3 questions: “I have no problem counseling cancer pa- tients’ sexual dysfunction”; “I have a theoretical knowledge or a theoretical treatment plan for cancer patients’ sexual dysfunction”, and “I provide proper care to cancer patients with sexual dysfunction.”

The fifth domain pertained challenges or difficulties when faced with cancer patients’ sexual dysfunction.

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of respondents Characteristic No. of respondents

(n=326) %

Overall Male Female Doctor Nurse Doctors Surgeon Physician Specialist Residents Male doctor Female doctor Urologist Non-Urologist

97 229 157 169 81 76 101 56 93 64 15 142

29.8 70.2 48.2 51.8 51.6 48.4 64.3 35.7 59.2 40.8 9.6

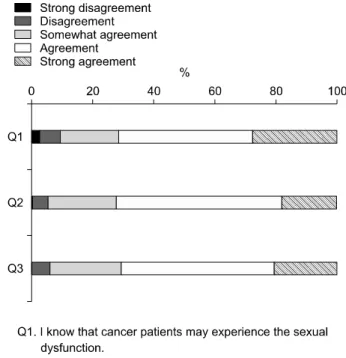

90.4 Fig. 1. Awareness of cancer patient's sexual problems.

This domain was consisted of 3 questions: “I have dif- ficulty in behaving naturally when I counsel cancer patients about their sexual dysfunction”; “I don’t know the theoretical knowledge, so I have difficulty in treating cancer patients’ sexual dysfunction”, and “I feel that I need to learn a theoretical knowledge about the cancer patients’ sexual dysfunction.”

All questions are multiple choice in nature. The an- swers were consisted of: “strongly disagree”, “disagree”,

“somewhat agree”, “agree”, and “strongly agree” or

“never”, “seldom”, “somewhat”, “frequently”, and

“always”, depending on the question.

This research received the approval of the in- dependent review board of Samsung Medical Center, Seoul, Korea. Using e-mails, the questionnaires were disseminated in March 2009. Differences in question 1, 2 in domain 2, question 3 in domain 3, and quse- tion1 in domain 5 between different groups were eval- uated with the chi-square test. All reported p values were two tailed, and all data analyses were conducted using the SPSS statistical software package (SPSS 13).

Results

Three hundred and twenty-six (n=326) men and women completed the questionnaires. The response rate was 85.4%. Table 1 summarizes the demographic characteristics of the respondents.

1. Awareness

In response to question 1, 90.5% (295/326) of re- spondents agreed, ranging from “strongly” to

“somewhat”. There were respectively 90, 143, and 62 respondents who expressed strong agreement, agree- ment and somewhat agreement. To question 2, 94.5%

(308/326) of respondents agreed. Respectively 59, 176, and 73 respondents expressed strong agreement, agree- ment and somewhat agreement. As for question 3, 94.1% (307/326) of respondents agreed. Respectively 67, 163, and 77 respondents expressed strong agree- ment, agreement and somewhat agreement. Most sur- vey participants were aware of cancer patients’ sexual problem and its importance (Fig. 1).

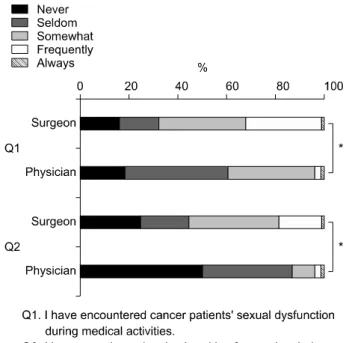

2. Experience

In response to question 1, 52.7% (172/326) expressed affirmatively. Respectively 2, 41, and 129 respondents expressed “always”, “frequently” and “somewhat”.

Regarding question 2, 29.4% (96/326) answered the affirmative. Respectively 2, 23, and 71 respondents ex- pressed “always”, “frequently” and “somewhat”. In

Fig. 2. Expirences of cancer patients' sexual problem.

Fig. 3. Expirence of cancer patients' problems among speciltities.

*p<0.001.

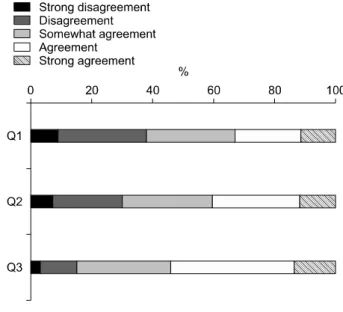

Fig. 4. Attitude toward cancer patient's sexual problems.

comparison with the awareness domain, fewer medical professionals give an affirmative answer. Particularly, physicians experienced cancer patients’ sexual problem less frequently than surgeons. Respectively 39.5%

(30/76) and 67.95% (55/81) of physicians and sur- geons gave an affirmative answer in question 1 (p=

0.0006). Respectively, 13.2% (10/76) and 55.6% (45/81) of physicians and surgeons gave an affirmative answer in question 2 (p<0.0001) chi-square test (Fig. 2, 3) 3. Attitude

In response to question 1, 18.7% (61/326) of re- spondents agreed, ranging from strongly to somewhat.

Respectively 1, 17, and 43 respondents expressed strong agreement, agreement and somewhat agree- ment. In question 2, 54.6% (178/326) of respondents agreed. Respectively 42, 49, and 87 respondents ex- pressed strong agreement, agreement and somewhat agreement. In question 3, 51.8% (169/326) of re- spondents agreed. Respectively 60, 53, and 56 re- spondents expressed strong agreement, agreement and somewhat agreement. When patients complaint of sex- ual problems, the majority of medical professionals tried to resolve the issue. In addition, residents recom-

mended appointments with urologists for counseling less frequently than specialists (59.4% (60/101) vs.

Fig. 5. Treatment behavior. Fig. 6. Problem recognition.

46.4% (26/56). But there is no significant difference (p=0.1622) (Fig. 4).

4. Treatment behavior

Fifty-five point five percent (55.5%) of respondents expressed no problems with counseling cancer patients about their sexual problems and fewer medical pro- fessionals gave affirmative answers on knowledge (36.5%) and management (27.6%). In response to question 1, 55.5% (181/326) agreed, ranging from strongly to somewhat. Respectively 17, 89, and 75 re- spondents expressed strong agreement, agreement and somewhat agreement. In question 2, 36.5% (119/326) of respondents agreed. Respectively 7, 32, and 80 re- spondents expressed strong agreement, agreement and somewhat agreement. In question 3, 27.6% (90/326) of respondents agreed. Respectively 3, 12, and 75 re- spondents expressed strong agreement, agreement and somewhat agreement (Fig. 5).

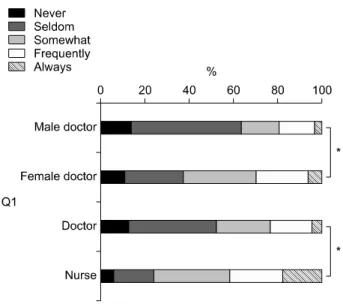

5. Problem recognition

In response to question 1, 61.7% (201/326) of re- spondents agreed, ranging from strongly to somewhat.

Strong agreement, agreement and somewhat agreement were expressed by 36, 70, and 95 respondents, respec- tively.

In question 2, 69.6% (227/326) of respondents agreed.

Respectively 37, 94, and 96 respondents expressed strong agreement, agreement and somewhat agree- ment. In question 3, 84.0% (274/326) of respondents agreed. Respectively 45, 130, and 99 respondents ex- pressed strong agreement, agreement and somewhat agreement.

Most survey participants (84.0%) felt that theoretical knowledge on the cancer patients’ problems is needed.

The extent of communicational challenge differs de- pending on sex and occupation. Female doctors had more difficulty than male doctor (34/93 vs. 40/64;

p=0.0024) and nurses had more difficulties than doc- tors (127/166 vs. 75/158; two-tailed p=0.0001) (Fig. 6, 7).

Discussion

Cancer patients are living longer and have become increasingly concerned about their QoL. One QoL do-

Fig. 7. Difficulties when facing sexual problem among gender and ocupation. *p<0.001.

main that may be negatively impacted by cancer is sexuality. Diagnosis with and treatment for cancer could seriously impact sexuality that exerts effects on physical, emotional, and social well-being.20 Physical changes from surgery and radiation can cause the atro- phy of the external genitalia and injury of the adjacent nervous system. This can lead to male and female sex- ual arousal disorders, dyspareunia, and orgasmic dys- function. Side effects associated with chemotherapy, such as alopecia, nausea, and fatigue are often related to decreased sexual desire.21,22 Emotionally, cancer di- agnosis could cause sexual problem due to depression, change in body image due to surgical scars, and feel- ings of loss of masculinity or femininity caused by hormonal therapies.23,24 In interpersonal relationships, changes from couples to patient-caregiver relationship threatens established sexual roles and interest.25,26 The impact of cancer and its treatment on sexuality are im- portant, because sexual concerns are strongly related to QoL, including symptom severity, disease-related interference, and disease-related distress.

A number of recent medical advances to enable manage of patients whose sexuality suffers as a result of cancer. Medication such as phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitors, intraurethral alprostadil and intracavernous

injection therapy and surgery, including penile im- plants, can mitigate erectile dysfunction. Lubricants can ease painful intercourse. Vaginal dilator for com- pliance and gaining optimal comfort, local vaginal es- trogen products for restoring vaginal integrity and in- travaginal dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) for provid- ing local tissue synthesis of estrogen and testosterone can be also used for female patients.27

However, discussing sex-related topics is still re- pressed in patient-doctor encounters in South Korea.

This may be because Koreans are reluctant to consult doctors about sexual issues. The Global Survey of Sexual Attitudes and Behaviors,28 which investigated various aspects of sex and relationships among 27,500 men and women aged 40 to 80 years from 29 coun- tries, revealed that men and women in East Asia (Korea, China, Hong Kong, Taiwan, and Japan) were the least likely to talk to a doctor about their sexual problems. As reasons for not consulting a doctor, East Asian men and women responded “I didn’t think it was a medical problem” and “I didn’t think a doctor could do much for me”. Although the beliefs of the Korean people regarding sexual morality have changed considerably in the intervening period, it is obvious that strong hesitation to consult someone about sexual issues still exists among Korean people. Under these circumstances, the medical professional have to posses an active attitude to enquire about their patients’ sex- ual problems.

In this study we found that only 38.3% of re- spondents had no or little difficulty in behaving natu- rally when counseling cancer patients about their sex- ual dysfunction. This is lower in proportion when compared to other Western studies, in which 67%

claimed that they were comfortable talking with pa- tients about sexuality and more than 60% stated they were comfortable in initiating such discussions.29,30 Particularly, female doctors and nurses more often ex- perience embarrassment when addressing sexuality with patients (Fig. 7). Considering the increasing num- ber of female doctors in South Korea and the fact that patients have more chances to discuss their problems with nurses than doctors, this is somewhat disappo- inting. We hypothesize that continuing education activ-

ities and a well- organized referring system to special- ists are needed, which can assist female doctors and nurses to adequately address the sexual concerns of their patients. In addition, making cancer patients com- plete and submit a questionnaire on sexual dysfunction and refer to specialists for sexual problems identified by the questionnaire may be an alternative way for pa- tients unwilling to discuss their sexual problems.

In addition to perception on sex, our data showed that medical professionals have little experience man- aging patients’ sexual dysfunction. In addition, physi- cians experience cancer patients’ sexual problems less frequently than surgeons. As such, education should focus the patient who receiving chemotherapy on that decreased sexual desire could be also other type of sexual dysfunction and could impact QoL.

In contrast to attitude and experience, previous data suggest that participants in this study displayed a clear awareness on to how cancer treatment and cancer it- self altered sexuality (90.5%), and how it can be a genuine concern for patient (94.5%). This is level with or higher than studies reported in Western countries.

Stead et al. reported that oncology nurses recognized that at least 75% of women with ovarian cancer would experience sexual problems. According to William et al., over 80% of participants disagreed that sex would be the furthest thing from their mind if they personally developed cancer.29,31 Moreover, the majority of partic- ipants tried to resolve sexual problems they faced. The fact that over 90% of healthcare professionals noticed cancer patients’ sexual problem and its importance, and many of them possess a positive manner is en- couraging, because this implies that participants have motivation to learn about cancer patients’ sexual prob- lem, which is associated with good educational s. This is another reason to educate healthcare professionals on problems faced by cancer patients.

In addition, most respondents felt that there is a lack of treatment expertise. Modern medicine rapidly evolves, and it is challenging to keep ones’ specialty knowledge up-to-date. So, well-organized referring system to specialists and public relations that specialist could help their problem might be needed for patients and medical professional.

We believe that the findings of this study is im- portant, because it remains the first survey conducted the healthcare professionals’ practices and attitudes to- ward cancer patients’ sexual issues in South Korea.

These data could be used as baseline to further re- search and served as evidence to educate healthcare professionals on their cancer patients’ sexual problems.

Further research is needed to determine the factors that influence the healthcare professionals’ attitudes toward their cancer patients’ sexuality, and the effective ways to promote doctors’ attitude and knowledge on this issues.

Conclusions

Most healthcare professionals agreed that the sexual problems of cancer patients are important for their QoL. However, they frequently felt a lack of commu- nicating skills and theoretical knowledge. Education programs on this issue for healthcare professionals and the implementation of a contact system with specialists should be appropriately established.

REFERENCES

1) Won YJ, Sung J, Jung KW, Kong HJ, Park S, Shin HR, et al. Nationwide cancer incidence in Korea, 2003-2005. Cancer Res Treat 2009;41:122-31 2) Andersen BL. Sexual functioning morbidity among

cancer survivors. Current status and future research directions. Cancer 1985;55:1835-42

3) Catalona WJ, Carvalhal GF, Mager DE, Smith DS.

Potency, continence and complication rates in 1,870 consecutive radical retropubic prostatectomies. J Urol 1999;162:433-8

4) Fulmer BR, Bissonette EA, Petroni GR, Theodorescu D. Prospective assessment of voiding and sexual function after treatment for localized prostate carci- noma: comparison of radical prostatectomy to hor- monobrachytherapy with and without external beam radiotherapy. Cancer 2001;91:2046-55

5) Guillonneau B, Cathelineau X, Doublet JD, Baumert H, Vallancien G. Laparoscopic radical prostatectomy:

assessment after 550 procedures. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 2002;43:123-33

6) Katz R, Salomon L, Hoznek A, de la Taille A, Vordos D, Cicco A, et al. Patient reported sexual function following laparoscopic radical prostatec- tomy. J Urol 2002;168:2078-82

7) Kundu SD, Roehl KA, Eggener SE, Antenor JA, Han M, Catalona WJ. Potency, continence and com- plications in 3,477 consecutive radical retropubic prostatectomies. J Urol 2004;172:2227-31

8) Potosky AL, Davis WW, Hoffman RM, Stanford JL, Stephenson RA, Penson DF, et al. Five-year out- comes after prostatectomy or radiotherapy for pros- tate cancer: the prostate cancer outcomes study. J Natl Cancer Inst 2004;96:1358-67

9) Schover LR, Evans R, von Eschenbach AC. Sexual rehabilitation and male radical cystectomy. J Urol 1986;136:1015-7

10) Krouse R, Grant M, Ferrell B, Dean G, Nelson R, Chu D. Quality of life outcomes in 599 cancer and non-cancer patients with colostomies. J Surg Res 2007;138:79-87

11) Jensen PT, Groenvold M, Klee MC, Thranov I, Petersen MA, Machin D. Early-stage cervical carci- noma, radical hysterectomy, and sexual function. A longitudinal study. Cancer 2004;100:97-106

12) Robinson JW. Sexuality and cancer. Breaking the silence. Aust Fam Physician 1998;27:45-7

13) Fobair P, Stewart SL, Chang S, D'Onofrio C, Banks PJ, Bloom JR. Body image and sexual problems in young women with breast cancer. Psychooncology 2006;15:579-94

14) Barni S, Mondin R. Sexual dysfunction in treated breast cancer patients. Ann Oncol 1997;8:149-53 15) Burwell SR, Case LD, Kaelin C, Avis NE. Sexual

problems in younger women after breast cancer surgery. J Clin Oncol 2006;24:2815-21

16) Ganz PA, Rowland JH, Desmond K, Meyerowitz BE, Wyatt GE. Life after breast cancer: under- standing women's health-related quality of life and sexual functioning. J Clin Oncol 1998;16:501-14 17) Al-Ghazal SK, Fallowfield L, Blamey RW. Does

cosmetic outcome from treatment of primary breast cancer influence psychosocial morbidity? Eur J Surg Oncol 1999;25:571-3

18) Walsh PC. Defining sexual outcomes after treatment

for localized prostate carcinoma. J Urol 2003;169:

1594-5

19) Carmack Taylor CL, Basen-Engquist K, Shinn EH, Bodurka DC. Predictors of sexual functioning in ovarian cancer patients. J Clin Oncol 2004;22:881-9 20) Reese JB, Keefe FJ, Somers TJ, Abernethy AP.

Coping with sexual concerns after cancer: the use of flexible coping. Support Care Cancer 2010;18:785- 800

21) Ganz PA, Kwan L, Stanton AL, Krupnick JL, Rowland JH, Meyerowitz BE, et al. Quality of life at the end of primary treatment of breast cancer: first results from the moving beyond cancer randomized trial. J Natl Cancer Inst 2004;96:376-87

22) Schover LR. Sexual rehabilitation after treatment for prostate cancer. Cancer 1993;71(Suppl 3):1024-30 23) Galbraith ME, Crighton F. Alterations of sexual

function in men with cancer. Semin Oncol Nurs 2008;24:102-14

24) Hughes MK. Alterations of sexual function in wom- en with cancer. Semin Oncol Nurs 2008;24:91-101 25) Schover LR. Sexuality and fertility after cancer.

Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program 2005:

523-7

26) Tierney DK. Sexuality: a quality-of-life issue for cancer survivors. Semin Oncol Nurs 2008;24:71-9 27) Sadovsky R, Basson R, Krychman M, Morales AM,

Schover L, Wang R, et al. Cancer and sexual problems. J Sex Med 2010;7:349-73

28) Moreira ED Jr, Brock G, Glasser DB, Nicolosi A, Laumann EO, Paik A, et al. Help-seeking behaviour for sexual problems: the global study of sexual atti- tudes and behaviors. Int J Clin Pract 2005;59:6-16 29) Williams HA, Wilson ME, Hongladarom G,

McDonell M. Nurses' attitudes toward sexuality in cancer patients. Oncol Nurs Forum 1986;13:39-43 30) Williams HA, Wilson ME. Sexuality in children and

adolescents with cancer: pediatric oncology nurses' attitudes and behaviors. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs 1989;

6:127-32

31) Stead ML, Brown JM, Fallowfield L, Selby P. Lack of communication between healthcare professionals and women with ovarian cancer about sexual issues.

Br J Cancer 2003;88:666-71

Appendix.

Questionnaires regarding's Awareness and Attitude toward the Sexuality of Cancer Patients

1. Recognition of sexual dysfunction in cancer patients by healthcare professionals.

i. “I know that cancer patients may experience the sexual dysfunction”

ii. “I think that the cancer patients’ sexual dysfunction is important to QoL”

iii. “I think that listening to their sexual problem is important”

2. Experience of facing cancer patients’ sexual dysfunction.

i. “I have encountered cancer patients’ sexual dysfunction during medical activities”

ii. “I have experienced patients asking for sexual dysfunction therapy”

3. Attitude to cancer patients who may suffer from sexual dysfunction.

i. “I have a positive manner about cancer patients’ sexual dysfunction”

ii. “If cancer patients ask for their sexual dysfunction treatment, I try to resolve the problem”

iii. “When the cancer patients complain of sexual dysfunction, I refer to a specialist”

4. Capacity for sexual dysfunction treatment.

i. “I have no problem counseling cancer patients’ sexual dysfunction”

ii. “I have a theoretical knowledge or a theoretical treatment plan for cancer patients’ sexual dysfunction”

iii. “I provide proper care to cancer patients with sexual dysfunction”

5. Challenges or difficulties when faced with cancer patients’ sexual dysfunction.

i. “I have difficulty in behaving naturally when I counsel cancer patients about their sexual dysfunction”

ii. “I don’t know the theoretical knowledge, so I have difficulty in treating cancer patients’ sexual dysfunction”

iii. “I feel that I need to learn a theoretical knowledge about the cancer patients’ sexual dysfunction”