관련 문서

An Updated Report by the American Society of Anesthesiologists Development Committee on Perioperative Blood Management (2015), the Association of Anaesthetistis of Great Britain

_____ culture appears to be attractive (도시의) to the

It considers the energy use of the different components that are involved in the distribution and viewing of video content: data centres and content delivery networks

After first field tests, we expect electric passenger drones or eVTOL aircraft (short for electric vertical take-off and landing) to start providing commercial mobility

1 John Owen, Justification by Faith Alone, in The Works of John Owen, ed. John Bolt, trans. Scott Clark, "Do This and Live: Christ's Active Obedience as the

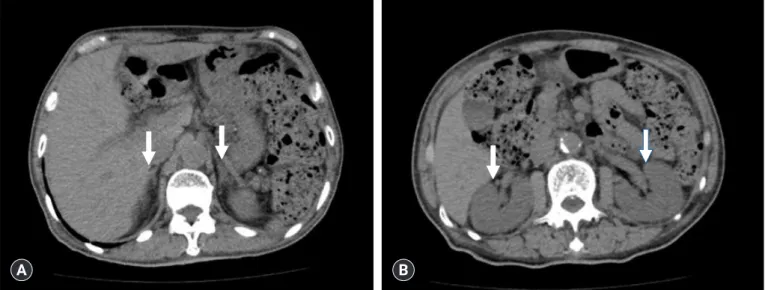

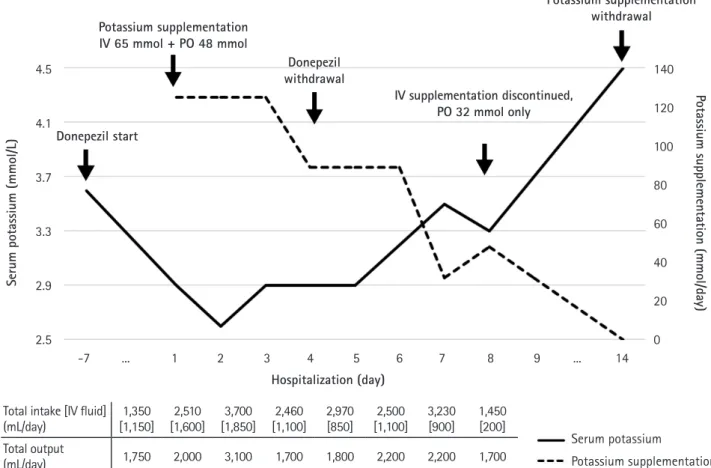

Dehydration Hypoxia Metabolic alkalosis Hypoglycemia Hypokalemia Hypothyroidism Constipation Anemia Constipation.. Excessive

The purpose of this study is to investigate the cognitive meanings of English causative verbs such as make make make make, have have have have, , , le , le let,

The purpose of this research is to confirm whether voluntary early morning physical exercise effects on the emotional and behavioral development of