Cytomegalovirus Infection Mimicking Recurrence of Malignant Lymphoma: A Case Report

Sae-Mee Park

1, Young Bae Choi

2and Joon Kee Lee

1Department of Pediatrics,

1Chungbuk National University Hospital, Cheongju,

2Ajou University School of Medicine, Ajou University Hospital, Suwon, Korea

When a patient with malignant lymphoma develops new lymph node enlargement, a recurrence of lymphoma is usually suspected first. However, painless and rapid lymph node enlargement, a manifestation of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, could also be due to other causes. A 3-year-old boy who was previously diagnosed with Burkitt lymphoma was admitted for routine tumor evaluation one year following completion of treatment. Abdominal computed tomography showed several enlarged lymph no- des in the right lower quadrant, and

18F-fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose positron emission tomography revealed hypermetabolic enlarged lymph nodes in the corresponding lesion. The patient underwent ileocecal lymph node biopsy for pathologic con- firmation, which revealed reactive hyperplasia without lymphoma recurrence. Sero- logic test results for cytomegalovirus immunoglobulin G and immunoglobulin M were positive. Additionally, the polymerase chain reaction test performed using a urine sample was positive for cytomegalovirus. After several outpatient follow-ups, we con- cluded cytomegalovirus infection that mimicked a recurrence of lymphoma on imag- ing as the cause for lymph node enlargements. This case highlights the importance of using prompt and multiple approaches after detecting a possible tumor recurrence through imaging studies.

pISSN 2233-5250 / eISSN 2233-4580 https://doi.org/10.15264/cpho.2021.28.1.58

Clin Pediatr Hematol Oncol 2021;28:58∼62Received on October 16, 2020 Revised on November 21, 2020 Accepted on December 29, 2020

Corresponding Author: Joon Kee Lee Department of Pediatrics, Chungbuk National University Hospital, 776 1-Sunhwan-ro, Seowon-gu, Cheongju 28644, Korea

Tel: +82-43-269-6340 Fax: +82-43-269-6064 E-mail: leejoonkee@gmail.com ORCID ID: orcid.org/0000-0001-8191-0812 Key Words: Burkitt lymphoma, Cytomegalovirus, Diagnostic imaging, Neoplasm re-

currence, Viral infections

Copyright ⓒ 2021 Korean Society of Pediatric Hematology-Oncology

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/

Introduction

When a patient with malignant lymphoma develops new lymph node (LN) enlargement, a recurrence of lym- phoma is usually first suspected. While LN enlargement is common in children with and without infectious con- ditions, manifestations of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma also include painless and rapid LN enlargement [1]. Healthy children and adolescents infected with cytomegalovirus (CMV) are mostly asymptomatic, except for approx- imately 10% of patients who acquire CMV infections that

present as CMV mononucleosis [2]. Herein, we present a case of CMV infection in which computed tomography (CT) and

18F-fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose positron emis- sion tomography (FDG-PET) imaging findings suggested tumor recurrence.

Case Report

A 3-year-old boy was admitted for his one-year post-treatment evaluation after completing multi-agent combination chemotherapy for Burkitt lymphoma (BL).

On admission, there were neither specific complaints nor

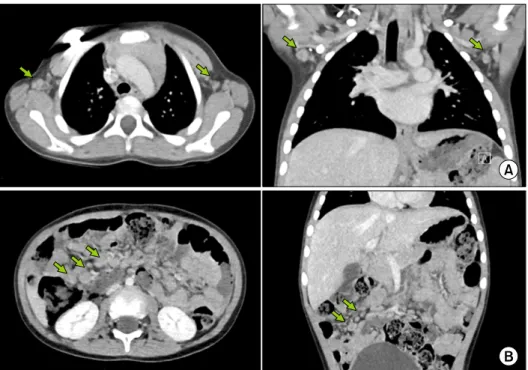

Fig. 1. Computed tomography scan showing enlargement of axillary (A) and abdominal (B) lymph nodes (indicated with green arrows).

any report of recent gastrointestinal illness from the pa- tient or his parents.

A diagnosis of BL was made 18 months before the pa- tient’s visit. Initial clinical presentation at the time of di- agnosis included a 4-5-cm-sized palpable mass in the right upper quadrant of the abdomen without any other LN enlargement. Further imaging work-up, including CT, FDG-PET, and bone scan, along with bone marrow eval- uation and cytospin of cerebral spinal fluid showed no metastasis. LN biopsies of the bulky abdominal mass were performed, and the final lymphoma staging was de- termined to be group B (stage III) according to the FAB/

LMB risk stratification [3]. Multi-agent chemotherapy us- ing methotrexate and rituximab was initiated on diag- nosis and for 6 months. Rituximab was used off-label based on the modified FAB/LMB 96 regimen [3]. The pa- tient achieved a complete response.

At the time of the present visit, the patient was alert and apparently healthy with soft abdomen, non-tender, and no distention signs. On palpation, there were no signs of an abdominal mass, hepatomegaly, or spleno- megaly. No LN enlargement was observed in the cervical, axillary, or inguinal area. The following examinations were scheduled and performed: complete blood cell

(CBC) count with differential; routine admission battery (serum); CT of the thorax, abdomen, and pelvis; bone scan.

The results of the CBC count with differential were as follows: leukocyte count, 7,190 cells/ µ L with lymphocyte dominancy (58.2%); hemoglobin concentration, 11.9 g/dL;

platelet count, 191,000 platelets/ µ L; absolute neutrophil count, 2,340 cells/ µ L. A peripheral blood smear revealed microcytic hypochromic red blood cells with anisopoiki- locytosis, increased white blood cell number with neu- trophilia, and toxic granules without atypical lympho- cytes. Moreover, normal platelet number suggesting the possibility of iron deficiency and reactive neutrophilia.

All the routine admission battery results, including the level of lactate dehydrogenase (344 IU/L) were within normal limits.

Abdominal CT showed several enlarged LNs (9-13 mm

in size) in the right lower quadrant and small bowel mes-

entery, whereas thoracic CT showed a few enlarged LNs

(8-12 mm) in both the axilla and right paratracheal nodal

stations (Fig. 1). Further work-up included FDG-PET,

which showed multiple newly developed hypermetabolic,

enlarged LNs, in the mesentery (maximum standardized

uptake value=3.3, Deauvill Criteria 4) (Fig. 2). Therefore,

Fig. 2.

18F-fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose positron emission tomography scan showing hypermetabolic enlarge- ment of axillary (A) and abdominal (B) lymph nodes (indicated with white arrows).

tumor recurrence was strongly suggested. An ileocecal LN biopsy was performed along with prophylactic ap- pendectomy to confirm the pathology of the lesion. The LN biopsy results revealed reactive hyperplasia with no malignancy evidence. Both the CMV immunohistochem- istry and in situ hybridization test results for Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) were negative, despite CD3 and CD20 antigen reactivity for T and B cells, respectively.

Multiple serologic tests, including those targeting anti- bodies for CMV, EBV, herpes simplex virus, varicella zos- ter virus, and hepatitis virus B/C were performed. All other serologic tests were negative except for CMV-Immuno- globulin G (IgG; 19.6 U/mL, negative<12-14 U/mL<pos- itive) and CMV-Immunoglobulin M (IgM; 22.5 U/mL, neg- ative<18-22 U/mL<positive).

Next, qualitative and quantitative polymerase chain reaction (PCR) tests were performed along with CMV cell cultures. Qualitative studies and cultures were performed using blood, urine, and saliva specimens. Quantitative real-time PCR was performed using an ethylenedia- minetetraacetic acid-treated blood sample. All speci- mens yielded negative culture and qualitative PCR re- sults; however, positive results were obtained for qual- itative PCR performed using urine. Real-time PCR showed

<1,000 copies/mL of CMV loads, which is within the ref- erence level. Furthermore, a CMV antigenemia assay showed a negative result.

The patient was discharged after asymptomatic CMV infection with no evidence of tumor recurrence. General physical examinations with serology and PCR follow-up were performed in the outpatient department. No abnor-

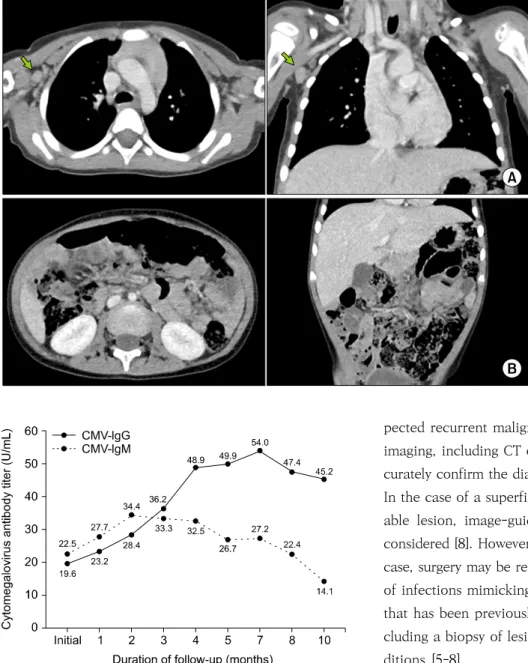

mal findings were detected on physical examination dur- ing the monthly follow-up visits that occurred over the year that followed. Follow-up CT imaging at 4 months showed a decrease in the size and number of LNs, except for a single LN at level 1 of the right axillae, which had decreased in size when evaluated using ultrasonography in the following month (Fig. 3). Further CT imaging at month 8 and 12 remained unchanged with no LN en- largement. However, PCR performed using urine and CMV IgG were persistently positive (Fig. 4). CMV IgM lev- els peaked (34.4 U/mL) at the 2-month follow-up and de- creased thereafter to a negative value at the 10-month follow-up (14.1 U/mL).

Written informed consent was obtained from the pa- tient’s parents for publication of any accompanying im- ages in the case report. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of our University Hospital (IRB no. 2019-11-025).

Discussion

We presented a case of CMV infection in which CT and

FDG-PET imaging findings mimicked those of tumor

recurrence. Despite performing pathologic work-up, dif-

ferentiating between acute EBV infection and lymphoma

may prove challenging [4]. However, considering that

EBV infection may cause certain lymphomas, the two

conditions may appear similar [1]. Previous cases of se-

lected infections mimicking the recurrence of certain

malignancies have been reported: Yersinia enterocolitica

mimicking gastrointestinal stromal tumor [5], M. tuber-

Fig. 3. Computed tomography scan at the 4-month follow-up showing a decrease in the size and number of axillary (A) and abdominal (B) lymph nodes except for a single lymph node at level one of the right axillae (indicated with green arrows).

Fig. 4. Level of cytomegalovirus antibody titer at follow-ups after the initial assessment. CMV, Cytomegalovirus; IgG, Immuno- globulin G; IgM, Immunoglobulin M.

culosis mimicking BL [6], and Pseudomonas aeruginosa mimicking breast cancer [7]. Nevertheless, to our knowl- edge, this is the first case of CMV mimicking lymphoma recurrence.

We learned two major lessons from our case: (1) the importance of pathologic confirmation of a lesion sug- gestive of neoplastic conditions, and (2) an individualized approach when determining the etiological agent of sus-

pected recurrent malignancy. After spotting a lesion on imaging, including CT or FDG-PET, the only way to ac- curately confirm the diagnosis is by performing a biopsy.

In the case of a superficial and, hence, easily approach- able lesion, image-guided core needle biopsy may be considered [8]. However, for deep lesions, such as in our case, surgery may be required. This is supported by cases of infections mimicking the recurrence of a malignancy that has been previously described in the literature, in- cluding a biopsy of lesions suggestive of neoplastic con- ditions [5-8].

Furthermore, highly prevalent local pathogens, in ad-

dition to more general pathogens, should be considered

as possible agents mimicking malignancy. In that sense,

we believe our case provides a good example. Based on

the geographic spread of CMV, it is more common to

come across such cases in a country where the seropre-

valence of CMV is relatively high. Although Korea is one

of the most industrialized member countries of the Or-

ganization for Economic Co-operation and Develop-

ment, the CMV seroprevalence, which could be an in-

verse surrogate marker of hygiene and socioeconomic

status, was estimated at 94% for all ages in Korea based

on a recent study [9]. We believe that our approach may not be limited to specific age groups or geographies.

Despite evidence supporting CMV infection in our pa- tient, we were unable to recognize CMV by antigen im- munohistochemistry of the resected LN; this constituted a significant limitation of the study. As studies on LN bi- opsies in CMV mononucleosis patients are scarce, we be- lieve that this finding is comparable with a study that conducted 6 liver biopsies from previously healthy adult patients with CMV mononucleosis [10].

In addition, the absence of CMV serology before the identification of CMV infection, and the uncertainty on the primary CMV infection remains the main limitations of the study. The positive results of urine CMV PCR sup- port the presence of the virus. The patient had positive CMV IgM titer for at least 8 months. CMV IgM antibodies are known to be detected for a period of 4 to 6 months after the onset of symptoms [11]. Nevertheless, consider- ing the usual duration of symptomatic patients, over 8 months of positive CMV IgM is still substantial. We spec- ulate that the influences of chemotherapy, including rit- uximab use, may exist, but further studies exploring this possibility are needed. Increased number of infections has been documented in patients treated with rituximab for lymphoma, and for viral pathogen, hepatitis B re- activation has been well documented [12]. Nevertheless, severe infection by CMV infection has been reported af- ter high-dose chemotherapy with autologous blood stem cell rescue and peritransplantation rituximab [13]. There- fore, even though the case was not a symptomatic severe viral infection, we believe that our case suggests the ne- cessity of considering opportunistic and viral infection for cases of LN enlargement in rituximab-treated pa- tients.

Our findings emphasize the importance of performing an immediate biopsy and using multiple approaches when attempting to explain lesions suggestive of neo- plastic conditions.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

References

1. Hochberg J, Goldman SC, Cairo MS. Lymphoma. In: Kliegman RM, ed. Nelson textbook of pediatrics. 21st ed. Philadelphia:

Elsevier, 2019;2656-66.

2. American Academy of Pediatrics. Cytomegalovirus infection.

In: Kimberlin DW, Brady MT, Jackson MA, Long SS, editors.

Red book 2018: report of the Committee on Infectious Dis- eases. 31st ed. Itasca: American Academy of Pediatrics, 2018;

310-7.

3. Goldman S, Smith L, Anderson JR, et al. Rituximab and FAB/

LMB 96 chemotherapy in children with Stage III/IV B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma: a Children’s Oncology Group report.

Leukemia 2013;27:1174-7.

4. Louissaint A Jr, Ferry JA, Soupir CP, Hasserjian RP, Harris NL, Zukerberg LR. Infectious mononucleosis mimicking lympho- ma: distinguishing morphological and immunophenotypic features. Mod Pathol 2012;25:1149-59.

5. Luedde T, Tacke F, Chavan A, Länger F, Klempnauer J, Manns MP. Yersinia infection mimicking recurrence of gastrointestinal stromal tumor. Scand J Gastroenterol 2004;39:609-12.

6. Omri HE, Hascsi Z, Taha R, et al. Tubercular meningitis and lymphadenitis mimicking a relapse of Burkitt’s lymphoma on (18)F-FDG-PET/CT: a case report. Case Rep Oncol 2015;8:

226-32.

7. Kucerova P, Cervinkova M. Spontaneous regression of tu- mour and the role of microbial infection--possibilities for cancer treatment. Anticancer Drugs 2016;27:269-77.

8. Tripathy S, Subudhi TK, Kumar R. Stoma site infection mim- icking lymphoma recurrence: potential pitfall on (18)F FDG positron emission tomography-computed tomography. Indian J Nucl Med 2019;34:233-4.

9. Choi SR, Kim KR, Kim DS, et al. Changes in cytomegalovirus seroprevalence in Korea for 21 Years: a single center study.

Pediatr Infect Vaccine 2018;25:123-31.

10. Snover DC, Horwitz CA. Liver disease in cytomegalovirus mononucleosis: a light microscopical and immunoperoxidase study of six cases. Hepatology 1984;4:408-12.

11. Chou S. Newer methods for diagnosis of cytomegalovirus in- fection. Rev Infect Dis 1990;12 Suppl 7:S727-36.

12. Gea-Banacloche JC. Rituximab-associated infections. Semin Hematol 2010;47:187-98.

13. Goldberg SL, Pecora AL, Alter RS, et al. Unusual viral in- fections (progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy and cy- tomegalovirus disease) after high-dose chemotherapy with autologous blood stem cell rescue and peritransplantation rituximab. Blood 2002;99:1486-8.