The Influence of Depression, Anxiety and Somatization on the Clinical Symptoms and Treatment Response in Patients with Symptoms of Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms Suggestive of Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia

This is the first study to investigate the influence of depression, anxiety and somatization on the treatment response for lower urinary tract symptoms/benign prostatic hyperplasia (LUTS/BPH). The LUTS/BPH patients were evaluated with the Korean versions of the International Prostate Symptom Score (IPSS), the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9), the 7-item Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale (GAD-7) and the PHQ-15. The primary endpoint was a responder rate defined by the total score of IPSS (≤ 7) at the end of treatment. The LUTS/BPH severity was significantly higher in patients with depression (whole symptoms P = 0.024; storage sub-symptom P = 0.021) or somatization (P = 0.024) than in those without, while the quality of life (QOL) was significantly higher in patients with anxiety (P = 0.038) than in those without. Anxious patients showed significantly higher proportion of non-response (odds ratio [OR], 3.294, P = 0.022) than those without, while somatic patients had a trend toward having more non-responders (OR, 2.552, P = 0.067). Our exploratory results suggest that depression, anxiety and somatization may have some influences on the clinical manifestation of LUTS/BPH. Further, anxious patients had a lower response to treatment in patients with LUTS/BPH. Despite of limitations, the present study demonstrates that clinicians may need careful evaluation of psychiatric symptoms for proper management of patients with LUTS/BPH.

Keywords: Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms; Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia; Depression;

Anxiety; Somatization; Response Yong June Yang,1 Jun Sung Koh,2

Hyo Jung Ko,3 Kang Joon Cho,2 Joon Chul Kim,2 Soo-Jung Lee,1 and Chi-Un Pae1,4

1Department of Psychiatry, The Catholic University of Korea College of Medicine, Seoul; 2Department of Urology, The Catholic University of Korea College of Medicine, Seoul; 3Department of Psychiatry, Seoul Metropolitan Eunpyeong Hospital, Seoul, Korea;

4Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Duke University Medical Center, Durham, NC, USA Received: 17 February 2014

Accepted: 8 May 2014 Address for Correspondence:

Chi-Un Pae, MD

Department of Psychiatry, Bucheon St. Mary’s Hospital, The Catholic University of Korea College of Medicine, 327 Sosa-ro, Bucheon 420-717, Korea

Tel: +82.32-340-7067, Fax: +82.32-340-2255 E-mail: pae@catholic.ac.kr

Funding: This work was supported by a grant of the Korean Health Technology R&D Project, Ministry of Health & Welfare, Republic of Korea (HI12C0003) and supported partly by Astellas.

http://dx.doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2014.29.8.1145 • J Korean Med Sci 2014; 29: 1145-1151

INTRODUCTION

Lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) manifest multiple do- main of clinical symptoms such as storage, voiding and post- micturition and are common among older men (1). Of the vari- ous etiologies and clinical symptoms associated with LUTS, be- nign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) is considered a primary cause and also closely resembles its symptoms, although a clear rela- tionship is not fully understood between LUTS and BPH (1-3).

The underlying pathophysiologies of LUTS/BPH are current- ly uncertain but it has been considered a subjective indicator of disease, not a confirmative formal diagnosis (4). According to a recent huge cross-sectional population-based study, the negative effects of LUTS/BPH were prominent across several domains of quality of Life (QoL) and on overall perceptions of general health status and mental health (5, 6). In addition, the clinical course of LUTS/BPH is chronic, recurrent and difficult-to-treat. Accor- ding to the recent large catchment area study with 5-yr follow-

up for natural history of LUTS (n = 5,502) (7), the prevalence of LUTS increased from 19% at baseline to 20% at follow-up. In particular, only less than half (43%) of those with moderate to severe LUTS at baseline remitted or become mild LUTS at fol- low-up; most men with severe LUTS at baseline continued to have severe LUTS (61.5%) at follow-up.

However, the treatment response with such medications is not satisfactory. A recent treatment guideline also suggests the weak efficacy of such medications, where approximately 20%- 50% reduction in LUTS/BPH symptoms are common after treat- ment of monotherapy of α-receptor blockers and 5α-reductase inhibitors based on results from a number of short-term and long-term clinical trials (8, 9).

Meanwhile, it was found that the clinical manifestation of LUTS/BPH is strongly associated with psychiatric disturbances such as depression, anxiety, and stress vulnerability, and im- pairments of instrumental activities during daily living in some studies (5, 10-17). For instance, the recent large cohort study Psychiatry & Psychology

(14) have also demonstrated the important relationship between LUTS/BPH and depression, in which depression was signifi- cantly associated with the severity of the diseases as well as it also involves in all stages of LUTS. According to a large observa- tional, longitudinal, multicenter study (n = 666), a substantial proportion (22.6%) of LUTS/BPH patients reported anxiety or depression and they also explained a 7% of variance for explain- ing the severity of LUTS/BPH. Likewise in a large population- based study (EpiLUTS, n = 30,000) (5), approximately 36% and 30% of men were found to report anxiety and depression, re- spectively. Pre-existing study results consistently suggest that putative role of psychiatric parameters in the development of LUTS/BPH and also proposes that the current treatment for LUTS/BPH may not fully ameliorate urinary issues if the under- lying psychiatric disturbances are not properly resolved (18).

Taken together, a high level of psychiatric morbidity has im- portant implications for the appropriate management in patients with of LUTS/BPH and warrants further in-depth studies in terms of potential relationship between psychiatric symptoms and treatment reponse in patients with LUTS/BPH (5). However, there has been a paucity of clinical data regarding a potential influence of such psychiatric disturbances on the treatment outcomes in patients with LUTS/BPH till today.

Therefore, the aim of this study was to investigate the poten- tial influences of depression, anxiety and somatisation on the treatment response in patients with LUTS/BPH with the use of brief, user-friendly and quick but validated rating scales since timely and proper measurement of such psychiatric parame- ters may help identify individuals more likely to benefit from treatment interventions in daily busy routine practice.

MATERIALS AND METHODS Subjects

Male patients with LUTS/BPH were recruited at an outpatient clinic in the Department of Urology at Bucheon St. Mary’s Hos- pital.

Principal inclusion criteria included men aged ≥ 40 yr, a clin- ical diagnosis of LUTS/BPH was evaluated by medical history, a careful physical examination and laboratory tests including prostate-specific antigen (PSA) levels. Few exclusion criteria were applied because the aims of the study were based on ob- servational approach. However, patients who exhibited the fol- lowing symptoms were excluded for diagnostic stability: 1) PSA level > 10 ng/mL, 2) a history or evidence of prostate cancer by prostate biopsy, 3) previous prostatic surgery, 4) any causes of LUTS other than BPH (i.e., neurogenic bladder, bladder neck contracture, urethral stricture, bladder malignancy, acute or chronic prostatitis, or acute or chronic urinary tract infections), and 5) speech or language deficits and cognitive dysfunction.

The study was a 12-week prospective observational design in

a naturalistic treatment setting. Alpha-blockers, 5-alpha-reduc- tase inhibitors or combination of both were the primary treat- ment utilised for the patients during the study. Throughout the study period, patients remained on the same medication and the same dosage as was given at the time of enrolment.

Rating scales

All the rating scales were examined at baseline and week 12.

The Korean versions of the International Prostate Symptom Score (IPSS) for severity of LUTS/BPH (19), the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) for depression (20, 21), the Patient Health Questionnaire-15 (PHQ-15) for somatization (22, 23) and the 7-item Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale (GAD-7) (24) for anxiety, were utilized in the study. The criteria for de- pression (≥ 5 on PHQ-9) (20), anxiety (≥ 5 on GAD-7) (24) and somatisation (≥ 5 on PHQ-15) (22) were defined by previous studies suggested.

Treatment outcomes

The primary endpoint of the study was a responder rate defined by the total score of IPSS (≤ 7) at the end of treatment (week 12). The 7 point response criterion was chosen since the IPSS total score of 7 indicates no or mild symptoms of LUTS/BPH.

Secondary endpoints included the changes in total scores and three sub-scores on the storage, obstruction, and QoL do- mains of the IPSS from baseline to week 12. Other responder analyses by different criteria included as follows: 1) ≥ 5 points and 2) ≥ 30% decrease from baseline to week 12 in IPSS total score from baseline to week 12 (25, 26). In LUTS/BPH clinical trials, regarding point decrease with IPPS total score, the 4 to 6 points decline was common and 3 points decrease was propos- ed to be the minimum for clinical benefit (26). Regarding % im- provement of IPSS total score from baseline, 25% and 30% re- ductions in IPSS total score were mostly utilized. However, none of point decrease or % reduction in IPSS total score has been validated as established response criteria, they were usually empirically used by individual research group. Hence, we have also empirically chosen the 5 point decrease and 30% improve- ment of IPSS total score as another potential response criteria.

Statistical analyses

Demographic variables were compared by the presence of de- pression, anxiety and somatization using Student’s t-test, a chi- square test with Yate’s correction, or Fisher’s test, as appropri- ate. To investigate the influence of each clinical parameter on various treatment outcomes, changes of individual rating scales from baseline to week 12 were analyzed using an analysis of co- variance (ANCOVA) controlling for age, duration of disease and type of medication. To analyze responders as defined a priori, Fisher’s exact tests were conducted. Odds ratio (OR) with 95%

confidence intervals (CIs) was also utilized for the responder

analysis as well.

Statistical significance was two-tailed and set at P < 0.05 and there was no adjustment for multiple comparisons because the sample size was relatively small. With these statistical parame- ters and after adjusting with covariates, the power of the sample to detect a medium effect size (d = 0.5) was 0.6108, which cor- responds to a difference of 2.6 in the mean changes of IPSS total scores between patients with depression and those without. All statistical analyses were conducted using the NCSS 2007® and PASS 2008® software (Kaysville, Utah, USA).

Ethics statement

The institutional review board of Bucheon St. Mary’s Hospital approved this study (IRB No. HC11OISE0004). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

RESULTS

Baseline demographic characteristics

Ninety three patients participated in the study. The mean age of the whole population was approximately 62 (61.7 ± 8.0) yr, and the majority of patients were married. More than half of patients exhibited comorbid medical diseases. The mean total score on the IPSS among all groups was approximately 17, indicating a

moderate severity of LUTS/BPH symptoms. The mean volume of prostate (PV) and peak flow rate (Qmax) were 36.8 ± 15.5 mL and 13.3 ± 1.9 mL/sec, respectively; however, PV and Qmax were not significantly different by presence of depression, anxiety and somatization (Table 1). In addition, the PV and Qmax were not significantly different as criteria of responders and non-re- sponders: 1) 33.2 ± 16.2 mL vs. 38.3 ± 15.0 mL and 13.5 ± 1.3 mL/sec vs. 13.3 ± 2.1 mL/sec, respectively, by IPSS at endpoint (≤ 7); 2) 38.2 ± 15.3 mL vs. 35.6 ± 15.8 mL and 13.1 ± 1.7 mL/

sec vs. 13.5 ± 2.1 mL/sec, respectively, by IPSS decrease from baseline (≥ 5) and 3) 36.6 ± 14.2 mL vs. 36.9 ± 16.5 mL and 13.4

± 1.3 mL/sec vs. 13.3 ± 2.3 mL/sec, respectively, by IPSS decrease from baseline (≥ 30%).

Depression subgroup

There were no group differences in demographic variables such as education level, family history of LUTS/BPH, economic sta- tus, comorbidity, alcohol history, smoking history, or marriage status between the two groups (data available on request). The LUTS/BPH total score was significantly higher in patients with depression than those without (18.5 vs. 15.3, P = 0.046). In the sub-symptom analysis, the storage sub-symptom was also sig- nificantly higher in patients with depression than in those with- out (7.6 vs. 5.8, P = 0.021). However, all the treatment outcomes

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of the subjects (n = 93)

Depression Anxiety Somatization

Presence (n = 35) Absence (n = 58) Presence (n = 38) Absence (n = 55) Presence (n = 46) Absence (n = 47)

Age (yr) 61.9 ± 7.9 61.3 ± 8.1 62.1 ± 8.3 61.5 ± 7.8 62.5 ± 8.0 61.0 ± 7.9

Duration of illness

(months) 11.9 ± 10.6 14.7 ± 17.8 16.9 ± 11.7 15.0 ± 14.3 13.9 ± 16.7 13.4 ± 14.3

IPSS total IPSS-Obs IPSS-Sto IPSS-QoL

18.5 ± 6.9 10.9 ± 4.5 7.6 ± 3.4 3.8 ± 1.4

15.3 ± 7.9*

9.4 ± 5.4 5.8 ± 3.7§ 3.3 ± 1.5

17.7 ± 6.5 10.7 ± 4.6 7.1 ± 3.1 3.8 ± 1.3

15.6 ± 8.3 9.5 ± 5.4 6.1 ± 3.9 3.2 ± 1.6ll

18.3 ± 7.3 11.0 ± 4.8 7.3 ± 3.5 3.7 ± 1.4

14.7 ± 7.6† 8.9 ± 5.3‡ 5.8 ± 3.6‡ 3.2 ± 1.5

PV (mL) 38.0 ± 15.3 36.1 ± 15.7 40.0 ± 14.9 34.6 ± 15.6 38.6 ± 16.6 35.1 ± 14.3

Qmax (mL/sec) 13.2 ± 1.8 13.4 ± 2.0 13.2 ± 1.7 13.4 ± 2.1 13.2 ± 1.7 13.5 ± 2.1

Medication AB alone 5ARI alone Combination

18 (51.4) 12 (34.3) 5 (14.3)

23 (39.7) 22 (37.9) 13 (22.4)

17 (44.7) 15 (39.5) 6 (15.8)

24 (43.6) 19 (34.5) 12 (21.8)

22 (47.8) 18 (39.1) 6 (13.0)

19 (40.4) 16 (34.0) 12 (25.5) Data represent mean ± standard deviation or number (%). *P = 0.046; †P = 0.024; ‡trend toward a significance; §P = 0.021; llP = 0.038. IPSS, International Prostate Symp- tom Score; Obs, obstruction; sto, storage; QoL, quality of life; AB, Alpha-blockers; 5ARI, 5-alpha-reductase inhibitors; combination = AB plus 5 ARI; Qmax, peak flow rate; PV, prostate volume.

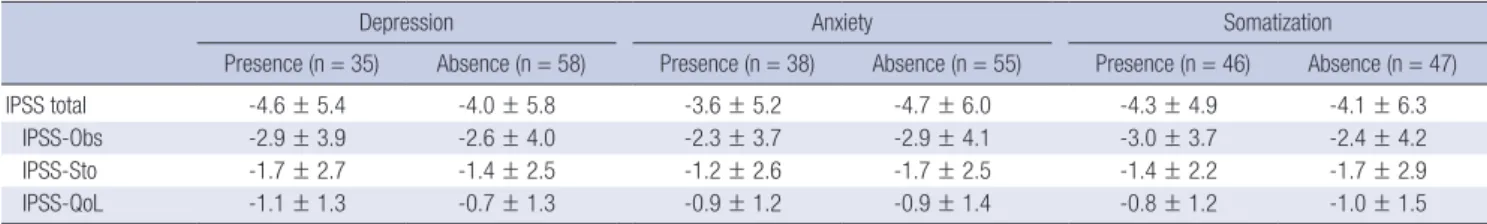

Table 2. The mean changes in total and sub-scores on IPSS during the study (n = 93)*

Depression Anxiety Somatization

Presence (n = 35) Absence (n = 58) Presence (n = 38) Absence (n = 55) Presence (n = 46) Absence (n = 47)

IPSS total -4.6 ± 5.4 -4.0 ± 5.8 -3.6 ± 5.2 -4.7 ± 6.0 -4.3 ± 4.9 -4.1 ± 6.3

IPSS-Obs -2.9 ± 3.9 -2.6 ± 4.0 -2.3 ± 3.7 -2.9 ± 4.1 -3.0 ± 3.7 -2.4 ± 4.2

IPSS-Sto -1.7 ± 2.7 -1.4 ± 2.5 -1.2 ± 2.6 -1.7 ± 2.5 -1.4 ± 2.2 -1.7 ± 2.9

IPSS-QoL -1.1 ± 1.3 -0.7 ± 1.3 -0.9 ± 1.2 -0.9 ± 1.4 -0.8 ± 1.2 -1.0 ± 1.5

Data represent mean ± standard deviation. *Analysis of Covariance, all P values are not significant. IPSS, International Prostate Symptom Score; Obs, obstruction; sto, storage;

QoL, quality of life.

were not different between the two groups (Tables 2, 3).

Anxiety subgroup

There were no group differences in demographic variables such as education level, family history of LUTS/BPH, economic sta- tus, comorbidity, alcohol history, smoking history, or marriage status between the two groups (data available on request). The LUTS/BPH total score was not different between the two groups.

QoL sub-score was significantly higher in patients with anxiety (3.8 vs. 3.2, P = 0.038) than in those without. Anxious patients showed significantly higher proportion of non-response (OR, 3.294, P = 0.022) than those without in primary endpoint analy- sis (Tables 2, 3).

Somatization subgroup

There were no group differences in demographic variables such as education level, family history of LUTS/BPH, economic sta- tus, comorbidity, alcohol history, smoking history, or marriage status between the two groups (data available on request). The LUTS/BPH total score was significantly higher in patients with somatization than in those without (18.3 vs. 14.7, P = 0.024). In addition, obstruction and storage sub-scores were in a trend to- ward a significant difference between the two groups (11.2 vs.

8.9 and 7.3 vs. 5.8, respectively, P = 0.050 and P = 0.050, respec- tively). There were no differences in all the treatment outcomes, although a trend toward a significant difference was found in primary endpoint analysis (P = 0.067) (Tables 2, 3).

DISCUSSION

Our preliminary results suggest that depression, anxiety and somatization may have partly influences on the clinical mani- festation of LUTS/BPH. Further, anxious patients had a lower response to treatment in patients with LUTS/BPH. The most strength of our study is to assess the relationship of depression, somatisation and anxiety with treatment response in patients

with LUTS/BPH for the first time, especially with the use of sim- ple, quick, reliable, well-validated, and self-administered rating scales which are easy to administer and interpret even in busy routine practice. However, the PV and Qmax were not signifi- cantly different by presence or absence of depression, anxiety, and somatization.

A common neurochemical underpinning may be speculated to be attributable to depression/anxiety/somatization and blad- der function. A compelling association between central and peripheral serotonin (5-HT)/norepinephrine (NE) systems and lower urinary tract function has been consistently proposed (27). In fact, duloxetine (serotonin/norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor, SNRI) has been approved for the treatment of urinary incontinence in Europe in 2004. It has been found to increases bladder capacity and urethral sphincter electromyographic ac- tivity in an animal model, which is mediated by increases in ex- tracellular 5-HT or NE (28). In addition, the reduction of 5-HT developed urinary frequency and caused detrusor over-activity, which was successfully reversed by fluoxetine the selective se- rotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) (29). Other studies (30) also suggest that the role of 5-HT in urinary function; 5-HT reuptake transporter knockout mice (-/-) demonstrated a bladder dys- function, characterized by significant increases in the frequen- cy of spontaneous non-voiding bladder contractions and de- creases in voiding volume. It was also found that the predomi- nant effect of NE release from sympathetic nerve terminals is on urethral contraction mediated through α1- and α2-adrenergic receptors (31-33). Therefore antidepressants such as SNRIs as well as SSRIs could be considered to enhance urine storage by decreasing bladder contractility and increasing outlet resistance.

In addition, the crucial role of serotonin and norepinephrine has been very-well known in the development and manage- ment of depression, anxiety and somatization, which are effec- tively controlled by SNRIs (34). In fact, depression, anxiety and somatisation have been found to impact on self-perception, treatment compliance, coping strategies and clinical status in a Table 3. The proportion of responders by different criteria in the study (n = 93)*

Response criteria Depression Anxiety Somatization

Presence (n = 35) Absence (n = 58) Presence (n = 38) Absence (n = 55) Presence (n = 46) Absence (n = 47)

≤ 7 in IPSS† Response

Nonresponse 7 (20.0)

28 (80.0) 20 (34.5)

38 (65.5) 6 (15.8)

32 (84.2)‡ 21 (38.2)

34 (61.8) 9 (19.6)

37 (80.4)§ 18 (38.3) 29 (61.7) 5 points responderll

Response

Nonresponse 18 (51.4)

17 (48.6) 24 (41.4)

34 (58.6) 15 (39.5)

23 (60.5) 27 (49.1)

28 (50.9) 22 (47.8)

24 (52.2) 20 (42.6)

27 (57.4) 30% responder¶

Response

Nonresponse 17 (48.6)

18 (51.4) 24 (41.4)

34 (58.6) 15 (39.5)

23 (60.5) 26 (47.3)

29 (52.7) 19 (41.3)

27 (58.7) 22 (46.8)

25 (53.2) Data represent number (%). *Fisher’s Exact test; †Response defined by a total score of ≤ 7 on the IPSS at week 12; ‡Odds ratio (OR) for nonresponse = 3.294 (95%

CIs = 1.073-10.530), chi-square = 5.410, P = 0.022; §trend toward a significant difference, OR for nonresponse = 2.552 (95% CIs = 0.913-7.255), chi-square = 3.959, P = 0.067; llResponse defined by 5 or more decrease in IPSS from baseline; ¶Responder defined 30% or more decrease in IPSS from baseline at week 12; 95% CIs, 95% con- fidence intervals. IPSS, International Prostate Symptom Score.

various mental health and physical diseases. Taken together, we may deliberately speculate that depression/anxiety/somati- zation and LUTS are all linked with major neurotransmitters, 5-HT and NE, and that thereby these psychiatric symptoms may play a role in the development of clinical symptoms and treatment outcomes in patients with LUTS/BPH.

Differential associations between psychiatric symptoms and LUTS were found in male patients in a previous study (5), where depression was more associated with storage and post-micturi- tion in male patients (5). Likewise the present study also found the association of storage symptoms and depression, support- ing the previous finding that depressed patients may have more bother in urinary frequency.

Many previous studies have replicated lower QoL in patients with LUTS/BPH were prominent across several domains of qual- ity of Life (QoL) and on overall perceptions of general health status and mental health, especially accompanied by depres- sion/anxiety. Likewise, we also found a significant association of anxiety with QoL in the present study, although depression did not show such relationship. This slight discrepancy may be caused by different sample characteristic, sample size, different measurement of depression and so on. Our findings partly sup- port the pre-existing study results.

The presence of anxiety and improvement of anxiety was sig- nificantly associated with the non-response in the present study, indicating that clinicians may benefit in expectation of future response in clinical practice if they know the level or improve- ment of anxiety. Our results are in line with the previous find- ings that anxiety may be involved as a risk factor in the severity and progression of LUTS/BPH (5, 16, 35).

An increasing evidence suggests the possibility that for some patients with LUTS/BPH (18, 35), CP/CPPS (36, 37) and urinary incontinence (38), urinary symptoms could be part of a soma- tizing process and requires further consideration (35). In fact, previous studies have consistently reported that the worse phys- ical health ratings are significantly associated with more bother in patients with LUTS/BPH, indicating that measures of urinary bother capture somatic distress should be necessary and that treating LUTS/BPH alone may not completely ameliorate uri- nary bother if underlying such somatic concerns are not addre- ssed (35).

Our preliminary study has a number of limitations and also implicates future study direction. First, the small sample size may be insufficient to detect such relationship between per- sonality and symptom severity of LUTS/BPH. Currently, there are no large and unselected population-based studies that have utilised the PHQ-9, PHQ-15, and GAD-7 on patients with LUTS/

BPH, and thus, the current results are entirely exploratory. The use of brief self-rating scales may be one of strength to be uti- lized in busy clinical practice but also could be a critical limita- tion; we propose to use of both subjective and objective rating

scale to verify depression, anxiety and somatization as well as including some assessment of current burden of stress. The study period was only 3 months and thus we do not know the long-term effects of such psychiatric parameters on the clinical course and treatment response. An additional dilemma for clin- ical researchers is whether to correct for multiple comparisons.

We did not perform multiple comparison correction in the pres- ent study due to the nature and small sample size of the study.

The Bonferroni correction is the most popular way to correct for the multiple testing issue, but its utility may depend on the nature of the study. According to Streiner and Norman (39), correction of multiple testing can be waived if a small number of hypotheses have been stated a priori or if the purpose of the study is exploratory (preliminary), and this is also in agreement with the assertions of other researchers (40). Finally, the sample was only recruited in one teaching hospital and may not repre- sent the general LUTS/BPH population.

In conclusion, the present study preliminarily demonstrates that clinicians may need careful evaluation of depression, anxi- ety and somatization issues for the proper management of pa- tients with LUTS/BPH, despite study limitations. Subsequent studies with adequately-powered and better design may be cru- cial to validate and support the present exploratory study find- ings.

DISCLOSURE

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

ORCID

Yong June Yang http://orcid.org/0000-0003-0135-0080 Jun Sung Koh http://orcid.org/0000-0001-7432-4209 Hyo Jung Ko http://orcid.org/0000-0002-9034-1524 Kang Joon Cho http://orcid.org/0000-0002-5305-901X Joon Chul Kim http://orcid.org/0000-0002-4019-620X Soo-Jung Lee http://orcid.org/0000-0002-1299-5266 Chi-Un Pae http://orcid.org/0000-0002-6774-9417

REFERENCES

1. Madersbacher S, Alivizatos G, Nordling J, Sanz CR, Emberton M, de la Rosette JJ. EAU 2004 guidelines on assessment, therapy and follow-up of men with lower urinary tract symptoms suggestive of benign prostatic obstruction (BPH guidelines). Eur Urol 2004; 46: 547-54.

2. Abrams P, Chapple C, Khoury S, Roehrborn C, de la Rosette J; Interna- tional Consultation on New Developments in Prostate Cancer and Pros- tate Diseases. Evaluation and treatment of lower urinary tract symptoms in older men. J Urol 2013; 189: S93-101.

3. Speakman MJ. Lower urinary tract symptoms suggestive of benign pros- tatic obstruction: what is the available evidence for rational manage- ment? Eur Urol 2001; 39: 6-12.

4. De la Rosette J. Definitions: LUTS, BPH, BPE, BOO, BPO. In: Bachmann A, de la Rosette J, editors. OUL benign prostatic hyperplasia and lower urinary tract symptoms in men. London: Oxford University Press, 2012.

5. Coyne KS, Wein AJ, Tubaro A, Sexton CC, Thompson CL, Kopp ZS, Ai- yer LP. The burden of lower urinary tract symptoms: evaluating the effect of LUTS on health-related quality of life, anxiety and depression: EpiLUTS.

BJU Int 2009; 103: 4-11.

6. Fourcade RO, Lacoin F, Rouprêt M, Slama A, Le Fur C, Michel E, Sitbon A, Cotté FE. Outcomes and general health-related quality of life among patients medically treated in general daily practice for lower urinary tract symptoms due to benign prostatic hyperplasia. World J Urol 2012;

30: 419-26.

7. Maserejian NN, Chen S, Chiu GR, Araujo AB, Kupelian V, Hall SA, McKin- lay JB. Treatment status and progression or regression of lower urinary tract symptoms in a general adult population sample. J Urol 2014; 191:

107-13.

8. Oelke M, Bachmann A, Descazeaud A, Emberton M, Gravas S, Michel MC, N’dow J, Nordling J, de la Rosette JJ; European Association of Urol- ogy. EAU guidelines on the treatment and follow-up of non-neurogenic male lower urinary tract symptoms including benign prostatic obstruc- tion. Eur Urol 2013; 64: 118-40.

9. Roehrborn CG. BPH progression: concept and key learning from MTOPS, ALTESS, COMBAT, and ALF-ONE. BJU Int 2008; 101: 17-21.

10. Parsons JK. Benign prostatic hyperplasia and male lower urinary tract symptoms: epidemiology and risk factors. Curr Bladder Dysfunct Rep 2010; 5: 212-8.

11. Taylor BC, Wilt TJ, Fink HA, Lambert LC, Marshall LM, Hoffman AR, Beer TM, Bauer DC, Zmuda JM, Orwoll ES, et al. Prevalence, severity, and health correlates of lower urinary tract symptoms among older men:

the MrOS study. Urology 2006; 68: 804-9.

12. Kupelian V, Wei JT, O’Leary MP, Kusek JW, Litman HJ, Link CL, McKin- lay JB; BACH Survery Investigators. Prevalence of lower urinary tract symptoms and effect on quality of life in a racially and ethnically diverse random sample: the Boston Area Community Health (BACH) Survey.

Arch Intern Med 2006; 166: 2381-7.

13. Robertson C, Link CL, Onel E, Mazzetta C, Keech M, Hobbs R, Four- cade R, Kiemeney L, Lee C, Boyle P, et al. The impact of lower urinary tract symptoms and comorbidities on quality of life: the BACH and URE- PIK Studies. BJU Int 2007; 99: 347-54.

14. Rom M, Schatzl G, Swietek N, Rücklinger E, Kratzik C. Lower urinary tract symptoms and depression. BJU Int 2012; 110: E918-21.

15. Wong SY, Hong A, Leung J, Kwok T, Leung PC, Woo J. Lower urinary tract symptoms and depressive symptoms in elderly men. J Affect Disord 2006; 96: 83-8.

16. Glover L, Gannon K, McLoughlin J, Emberton M. Men’s experiences of having lower urinary tract symptoms: factors relating to bother. BJU Int 2004; 94: 563-7.

17. Litman HJ, Steers WD, Wei JT, Kupelian V, Link CL, McKinlay JB; Bos- ton Area Community Health Survey Investigators. Relationship of life- style and clinical factors to lower urinary tract symptoms: results from Boston Area Community Health survey. Urology 2007; 70: 916-21.

18. Seyfried LS, Wallner LP, Sarma AV. Psychosocial predictors of lower uri- nary tract symptom bother in black men: the Flint Men’s Health Study. J Urol 2009; 182: 1072-7.

19. Choi HR, Chung WS, Shim BS, Kwon SW, Hong SJ, Chung BH, Sung

DH, Lee MS, Song JM. Translation validity and reliability of I-PSS Kore- an version. Korean J Urol 1996; 37: 659-65.

20. Han C, Jo SA, Kwak JH, Pae CU, Steffens D, Jo I, Park MH. Validation of the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 Korean version in the elderly popu- lation: the Ansan Geriatric Study. Compr Psychiatry 2008; 49: 218-23.

21. Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief de- pression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med 2001; 16: 606-13.

22. Han C, Pae CU, Patkar AA, Masand PS, Kim KW, Joe SH, Jung IK. Psy- chometric properties of the Patient Health Questionnaire-15 (PHQ-15) for measuring the somatic symptoms of psychiatric outpatients. Psycho- somatics 2009; 50: 580-5.

23. Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-15: validity of a new mea- sure for evaluating the severity of somatic symptoms. Psychosom Med 2002; 64: 258-66.

24. Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB, Löwe B. A brief measure for assess- ing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med 2006; 166:

1092-7.

25. Chapple CR, Montorsi F, Tammela TL, Wirth M, Koldewijn E, Fernán- dez Fernández E; European Silodosin Study Group. Silodosin therapy for lower urinary tract symptoms in men with suspected benign prostatic hyperplasia: results of an international, randomized, double-blind, pla- cebo- and active-controlled clinical trial performed in Europe. Eur Urol 2011; 59: 342-52.

26. Barkin J. Benign prostatic hyperplasia and lower urinary tract symptoms:

evidence and approaches for best case management. Can J Urol 2011;

18: 14-9.

27. Thor KB, Morgan C, Nadelhaft I, Houston M, De Groat WC. Organiza- tion of afferent and efferent pathways in the pudendal nerve of the female cat. J Comp Neurol 1989; 288: 263-79.

28. Thor KB, Katofiasc MA. Effects of duloxetine, a combined serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor, on central neural control of lower urinary tract function in the chloralose-anesthetized female cat. J Phar- macol Exp Ther 1995; 274: 1014-24.

29. Lee KS, Na YG, Dean-McKinney T, Klausner AP, Tuttle JB, Steers WD.

Alterations in voiding frequency and cystometry in the clomipramine induced model of endogenous depression and reversal with fluoxetine. J Urol 2003; 170: 2067-71.

30. Cornelissen LL, Brooks DP, Wibberley A. Female, but not male, seroto- nin reuptake transporter (5-HTT) knockout mice exhibit bladder insta- bility. Auton Neurosci 2005; 122: 107-10.

31. Springer JP, Kropp BP, Thor KB. Facilitatory and inhibitory effects of se- lective norepinephrine reupta`ke inhibitors on hypogastric nerve-evoked urethral contractions in the cat: a prominent role of urethral beta-ad- renergic receptors. J Urol 1994; 152: 515-9.

32. Danuser H, Bemis K, Thor KB. Pharmacological analysis of the norad- renergic control of central sympathetic and somatic reflexes controlling the lower urinary tract in the anesthetized cat. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 1995; 274: 820-5.

33. Danuser H, Thor KB. Inhibition of central sympathetic and somatic out- flow to the lower urinary tract of the cat by the alpha 1 adrenergic recep- tor antagonist prazosin. J Urol 1995; 153: 1308-12.

34. Marks DM, Shah MJ, Patkar AA, Masand PS, Park GY, Pae CU. Serotonin- norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors for pain control: premise and prom- ise. Curr Neuropharmacol 2009; 7: 331-6.

35. Cortes E, Sahai A, Pontari M, Kelleher C. The psychology of LUTS: ICI-

RS 2011. Neurourol Urodyn 2012; 31: 340-3.

36. Anderson RU, Orenberg EK, Chan CA, Morey A, Flores V. Psychometric profiles and hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis function in men with chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome. J Urol 2008; 179: 956- 60.

37. Lai HH, North CS, Andriole GL, Sayuk GS, Hong BA. Polysymptomatic, polysyndromic presentation of patients with urological chronic pelvic

pain syndrome. J Urol 2012; 187: 2106-12.

38. Walters MD, Taylor S, Schoenfeld LS. Psychosexual study of women with detrusor instability. Obstet Gynecol 1990; 75: 22-6.

39. Streiner DL, Norman GR. Correction for multiple testing: is there a reso- lution? Chest 2011; 140: 16-8.

40. Rothman KJ. No adjustments are needed for multiple comparisons. Epi- demiology 1990; 1: 43-6.