INTRODUCTION

The worldwide incidence of gastrointestinal cancer is relatively high compared with other cancers.1) Gastric cancers occur most frequently in males, and gastrointestinal cancers, including stomach, colon, rectum, liver, pancreas, and gallbladder cancer, are among the ten leading types of new cancer cases in both males and females in Korea.2) Although the overall incidence of advanced or metastatic gastrointestinal cancer has been lowered through early screening, and patients with early gastroin- testinal cancer can be cured by surgical resection, a large majority of pa- tients experience a relapse after surgical resection or are initially diag- nosed with locally advanced unresectable or metastatic disease.2,3) For patients with advanced gastrointestinal cancer requiring palliative ther- apy, the 5-year survival rate has been reported to be 1.7~19.0%.2-4)

Traditionally, the primary goal of cancer therapy has been to decrease tumor size and increase overall survival rate. However, indicators of the efficacy of cancer therapy have expanded to include not only survival rate, but also quality of life (QOL), and QOL is an independent prognos- tic factor for survival rate in cancer patients.5,6) QOL is an important outcome measure in all cancer patients, and is particularly critical in pa- tients with metastatic cancer as their treatment is limited to palliative therapy and cure is no longer the goal. QOL is a multidimensional con- cept that includes physical, psychological, social and cognitive function- ing, and the impact of illness and treatment on the patient’s life.7,8) Psy- chological distress such as anxiety or depression is common in cancer patients, reduces QOL, and increases mortality rate.9-11) Furthermore, psychological distress can change during the course of cancer treatment after initial diagnosis.12,13) Therefore, comprehensive and periodic patient assessment focused on psychological as well as physical aspects should be incorporated into the treatment process for cancer patients, particu- larly those with advanced or metastatic cancer. Although there are many studies on psychological distress and QOL in cancer patients,14-18) there are few studies on the relation between psychological distress and QOL in patients with advanced or metastatic gastrointestinal cancer.19,20)

The objective of this study was to assess the factors associated with

Anxiety and Depression as Predictive Factors for Quality of Life in Patients with Advanced Gastrointestinal Cancer

Chung, JungHwa1 · Kwon, Jihyun1 · Kim, Hyun Kyung2 · Ju, Gawon3 · Kim, Seung Taik1,4 · Han, Hye Sook1,4

1Department of Internal Medicine, Chungbuk National University Hospital, Cheongju; 2College of Nursing, Chonbuk Research Institute of Nursing Science, Chonbuk National University, Jeonju; 3Department of Psychiatry, Chungbuk National University Hospital, Cheongju; 4Department of Internal Medicine, College of Medicine, Chungbuk National University, Cheongju, Korea

Purpose: The purpose of the present study was to assess factors associated with quality of life (QOL) and to determine whether anxi- ety and depression are predictive of QOL in patients with advanced gastrointestinal cancer at initial diagnosis and during the treat- ment process. Methods: One hundred and twenty patients with gastrointestinal cancer requiring palliative chemotherapy were en- rolled. Results: At baseline, depression, performance status, and anxiety accounted for 55.0% (p<.001) of the variance in global health status score, depression accounted for 22.0% (p<.001) of the variance in functional scales score, and anxiety accounted for 19.0%

(p<.001) of the variance in symptom scales score. At 3 months, depression, pain, and performance status accounted for 72.0% (p<.001) of the variance in global health status score, 76.0% (p<.001) of the variance in functional scales score, and 74.0% (p<.001) of the vari- ance in symptom scales score. Conclusion: Anxiety and depression were significant predictive factors of QOL in patients with ad- vanced gastrointestinal cancer. Depression and performance status were significant predictive factors of QOL at both baseline and 3 months, and anxiety and pain were significant predictive factors of QOL at baseline and 3 months, respectively.

Key Words: Anxiety, Cancer, Depression, Gastrointestinal, Quality of Life

*JungHwa Chung and Jihyun Kwon contributed equally to this work.

Address reprint requests to: Han, Hye Sook

Department of Internal Medicine, College of Medicine, Chungbuk National University, Chungdae-ro 1, Seowon-gu, Cheongju 28644, Korea.

Tel: +82-43-269-6306 Fax: +82-43-273-3252 E-mail: sook3529@hanmail.net Received: Sep 20, 2016 Revised: Dec 5, 2016 Accepted: Dec 19, 2016

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0) which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

global health status, 0.91 for functional scales, and 0.81 for symptom scales, respectively. The use of EORTC QLQ-C30 in this study was ap- proved by the EORTC-QLQ Study group.

Emotional functioning including anxiety or depression and pain in EORTC QLQ-C30 were included in the analysis of the functional and symptom scales of EORTC QLQ-C30 for overall assessment of QOL.

Anxiety, depression, and pain were assessed by each assessment measure with proven reliability and validity. Anxiety and depression were evalu- ated using the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS), Korean version.24) The HADS is a 14-item questionnaire consisting of two sub- scales, anxiety and depression, each including seven items. Each item is scored on a four-point scale ranging from zero to three, and subscale scores range from zero, indicating no distress, to 21, indicating maxi- mum distress. A score≥8 on either of the two HADS subscales is consid- ered to be clinically significant. Oh et al.24) demonstrated the validity of measures of anxiety and depression and reported that Cronbach’s α co- efficients in HADS anxiety and depression were 0.89 and 0.86, respec- tively. In the present study, Cronbach’s α coefficients of HADS anxiety and depression were 0.88 and 0.82, respectively. The use of HADS Ko- rean version in this study was approved by the Korean Translater. Pain intensity was evaluated using a numeric rating scale (NRS) ranging from zero (no pain) to 10 (worst pain imaginable).

QOL, pain, anxiety, and depression were evaluated at initial diagnosis of advanced gastrointestinal cancer (study enrollment) and during the palliative treatment process (3 months after study enrollment). The rea- son for setting 3 months as the point of the palliative treatment process is that most of the patients will have active anticancer treatment at the 3 months after initial diagnosis even considering the gastrointestinal can- cer with poor prognosis such as liver, pancreas, and bile duct cancers.

3. Statistical analysis

Data are summarized as frequencies and percentages for categorical variables, and mean and standard deviation (SD) for continuous vari- ables. QOL, pain, anxiety, and depression were compared between base- line and 3 month time points using independent sample t-tests.

At both baseline and 3 months, QOL was compared across patients grouped according to age, sex, marital status, education level, employ- ment status, monthly income, ECOG PS, comorbid disease, primary site of tumor, and type of anticancer therapy using an independent sample t- test or one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). Statistically significant ANOVA results were followed up using Duncan’s post-hoc analysis. Re- QOL in Korean patients with advanced gastrointestinal cancer requir-

ing palliative chemotherapy at initial diagnosis of advanced cancer and during the palliative treatment process, and to determine whether anxi- ety and depression are predictive of QOL.

METHODS

1. Patient selection

All consecutive eligible patients treated at the Department of Gastro- intestinal Medical Oncology in Chungbuk National University Hospital were considered for this observational prospective study. The following inclusion criteria were applied: age>18 years; histologically confirmed advanced gastrointestinal cancer including esophagus, gastric, colorec- tal, liver, pancreas, and bile duct cancers; scheduled to receive palliative chemotherapy; Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) perfor- mance-status (PS) score≤2 (on a 5-point scale, with 0 indicating no symptoms and higher scores indicating increasing disability)21); life ex- pectancy≥3 months; ability to understand the Korean language; and normal cognitive function. Patients were excluded if they had a terminal condition, cognitive impairment, history of a psychological disorder or substance abuse, or a severe comorbid illness. This observational study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Chun- gbuk National University Hospital. Written informed consent was ob- tained from all participants prior to enrollment in the study.

2. Assessments

Sociodemographic data (marital status, education level, employment status, and monthly income) were obtained from standardized ques- tions. Clinical data (age, sex, ECOG PS, comorbid disease, primary site of tumor, and type of anticancer therapy) were obtained from a physi- cian’s assessment and the patient’s medical record.

QOL was evaluated using the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire C30 (EORTC QLQ-C30), Korean version 3.22) EORTC QLQ-C30 is organized into three subscales; global health status, function scales, and symptom scales.23) Higher scores for global health status and on the function scales indicate better overall QOL and level of functioning, and higher scores on the symptom scales indicate a higher level of symptomatology and worse QOL. Yun et al.22) confirmed the validity of EORTC QLQ-C30 Korean version and reported that Cronbach’s α coefficients ranged from 0.60 to 0.89. In the present study, Cronbach’s α coefficients were 0.89 for

RESULTS

1. Patient characteristics

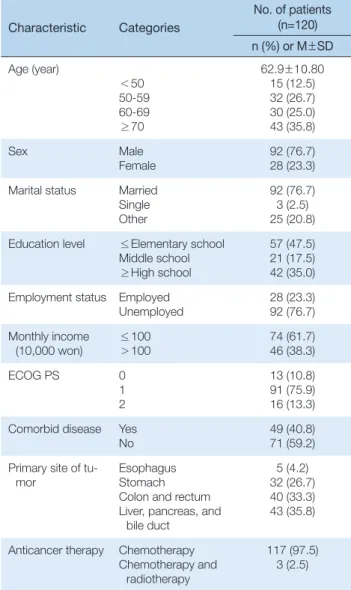

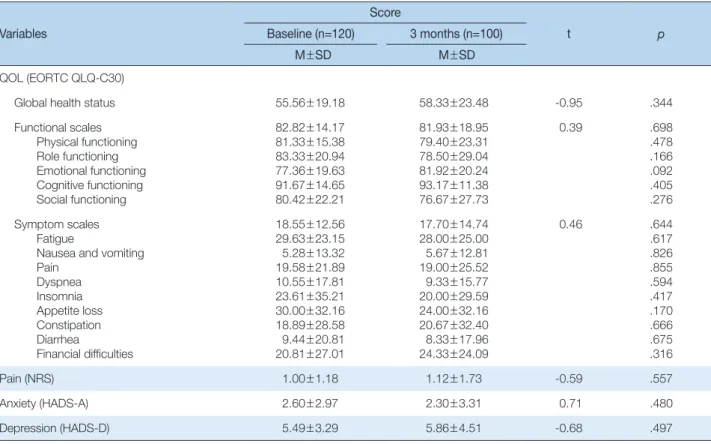

Of the 129 patients screened between July 2012 and June 2014, 120 were included in the study. Nine patients were excluded because of cog- nitive impairment (n=2), refusal to participate (n= 4), or inability to fill in the questionnaires (n=3)(Fig. 1). Of the 120 patients included in the study, 100 patients (83.3%) completed the anxiety, depression, and QOL evaluations at baseline and at 3 month time points, and 20 had incom- plete data at the 3 month time point because they were lost to follow-up (n=11) or died before the 3 month assessment (n=9)(Fig. 1). The so- ciodemographic and clinical characteristics of the 120 patients included in the study are shown in Table 1. There was no significant change in QOL (EORTC QLQ-C30 score), pain (NRS score), anxiety (HADS anx- iety score), or depression (HADS depression score) between baseline and 3 months (Table 2).

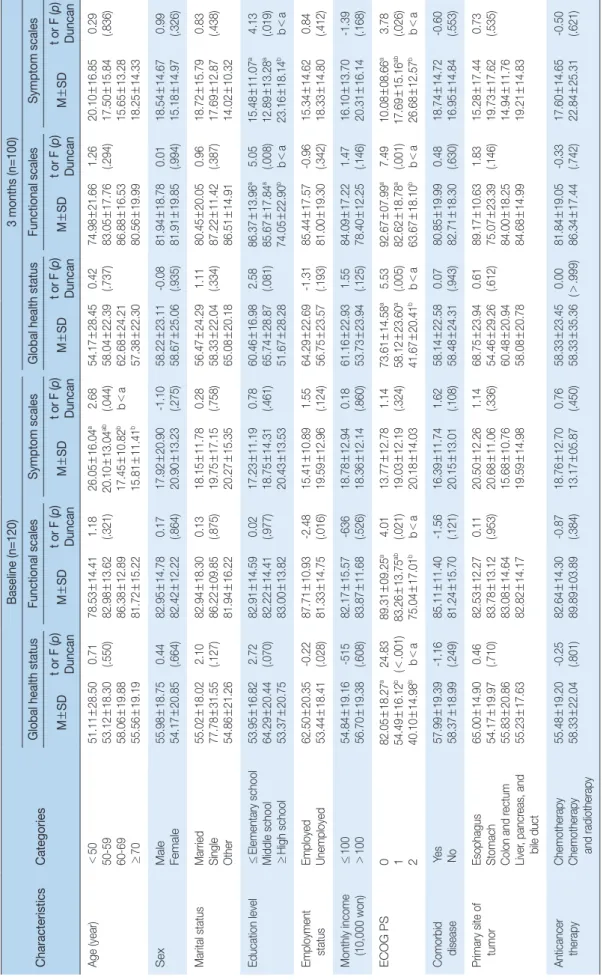

2. Sociodemographic and clinical factors associated with QOL QOL according to sociodemographic and clinical factors at baseline and 3 months are listed in Table 3. At baseline, the EORTC QLQ-C30 global health status score was greater in employed patients than in un- employed patients, greater in patients with low ECOG PS scores than in patients with high ECOG PS scores. The EORTC QLQ-C30 symptom scales score was greater (indicating worse QOL) in patients aged<50 years than in patients aged 50~59 years, 60~69 years, and>70 years, and greater in patients aged 50~59 years than in patients aged 60~69 years and>70 years.

At 3 months, the EORTC QLQ-C30 global health status score was greater in patients with low ECOG PS scores than in patients with high ECOG PS score. The EORTC QLQ-C30 functional scales score was greater in patients who had not completed high school than in patients who had completed high school, and greater in patients with low ECOG PS scores than in patients with with high ECOG PS score. The EORTC QLQ-C30 symptom scales score was greater (indicating worse QOL) in patients who had completed high school than in patients who had not completed high school, lower (indicating better QOL) in in patients with low ECOG PS score than in patients with high ECOG PS scores.

3. Correlations between QOL and pain, anxiety, and depression

lations between continuous variables (pain, anxiety, and depression) and QOL were quantified using Pearson’s correlation coefficients.

At both baseline and 3 months, factors affecting QOL were identified using a multiple regression analysis based on a stepwise method. Prior to the regression analysis, we performed an independent validation of the homoscedasticity and normality of errors. This was followed by the vali- dation of multicolinearity.

p<.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS for Windows software, version 18.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL).

Table 1. Sociodemographic and Clinical Characteristics (N=120) Characteristic Categories

No. of patients (n=120) n (%) or M±SD Age (year)

<50 50-59 60-69

≥70

62.9±10.80 15 (12.5) 32 (26.7) 30 (25.0) 43 (35.8)

Sex Male

Female 92 (76.7)

28 (23.3) Marital status Married

Single Other

92 (76.7) 3 (2.5) 25 (20.8) Education level ≤Elementary school

Middle school

≥High school

57 (47.5) 21 (17.5) 42 (35.0) Employment status Employed

Unemployed 28 (23.3)

92 (76.7) Monthly income

(10,000 won) ≤100

>100

74 (61.7) 46 (38.3)

ECOG PS 0

1 2

13 (10.8) 91 (75.9) 16 (13.3) Comorbid disease Yes

No 49 (40.8)

71 (59.2) Primary site of tu-

mor Esophagus

Stomach Colon and rectum Liver, pancreas, and

bile duct

5 (4.2) 32 (26.7) 40 (33.3) 43 (35.8)

Anticancer therapy Chemotherapy Chemotherapy and

radiotherapy

117 (97.5) 3 (2.5)

ECOG PS= Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group.

Fig. 1. Flow diagram showing patient selection.

QOL= quality of life.

Table 2. Quality of Life, Anxiety, and Depression at Baseline and 3 Months Variables

Score

t p

Baseline (n=120) 3 months (n=100)

M±SD M±SD

QOL (EORTC QLQ-C30)

Global health status 55.56±19.18 58.33±23.48 -0.95 .344

Functional scales Physical functioning Role functioning Emotional functioning Cognitive functioning Social functioning

82.82±14.17 81.33±15.38 83.33±20.94 77.36±19.63 91.67±14.65 80.42±22.21

81.93±18.95 79.40±23.31 78.50±29.04 81.92±20.24 93.17±11.38 76.67±27.73

0.39 .698

.478 .166 .092 .405 .276 Symptom scales

Fatigue

Nausea and vomiting Pain

Dyspnea Insomnia Appetite loss Constipation Diarrhea

Financial difficulties

18.55±12.56 29.63±23.15 5.28±13.32 19.58±21.89 10.55±17.81 23.61±35.21 30.00±32.16 18.89±28.58 9.44±20.81 20.81±27.01

17.70±14.74 28.00±25.00 5.67±12.81 19.00±25.52 9.33±15.77 20.00±29.59 24.00±32.16 20.67±32.40 8.33±17.96 24.33±24.09

0.46 .644

.617 .826 .855 .594 .417 .170 .666 .675 .316

Pain (NRS) 1.00±1.18 1.12±1.73 -0.59 .557

Anxiety (HADS-A) 2.60±2.97 2.30±3.31 0.71 .480

Depression (HADS-D) 5.49±3.29 5.86±4.51 -0.68 .497

QOL= Quality of life; EORTC QLQ-C30= European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer quality of life questionnaire-core 30; NRS= Numeric rating scale; HADS- A= Hospital anxiety and depression scale-anxiety; HADS-D= Hospital anxiety and depression scale-depression.

Table 3. Quality of Life according to Sociodemographic and Clinical Characteristics CharacteristicsCategories

Baseline (n=120)3 months (n=100) Global health statusFunctional scalesSymptom scales Global health statusFunctional scalesSymptom scales M±SDt or F (p) DuncanM±SDt or F (p) DuncanM±SDt or F (p) DuncanM±SDt or F (p) DuncanM±SDt or F (p) DuncanM±SDt or F (p) Duncan Age (year)<50 50-59 60-69 ≥70

51.11±28.50 53.12±18.30 58.06±19.88 55.56±19.19 0.71 (.550)78.53±14.41 82.98±13.62 86.38±12.89 81.72±15.22 1.18 (.321)26.05±16.04a 20.10±13.04ab 17.45±10.82b 15.81±11.41b

2.68 (.044) b<a

54.17±28.45 58.04±22.39 62.68±24.21 57.38±22.30 0.42 (.737)74.98±21.66 83.05±17.76 86.88±16.53 80.56±19.99 1.26 (.294)20.10±16.85 17.50±15.84 15.65±13.28 18.25±14.33

0.29 (.836) SexMale Female 55.98±18.75 54.17±20.850.44 (.664)82.95±14.78 82.42±12.220.17 (.864)17.92±20.90 20.90±13.23-1.10 (.275)58.22±23.11 58.67±25.06-0.08 (.935)81.94±18.78 81.91±19.850.01 (.994)18.54±14.67 15.18±14.970.99 (.326) Marital statusMarried Single Other

55.02±18.02 77.78±31.55 54.86±21.26 2.10 (.127)82.94±18.30 86.22±09.85 81.94±16.22 0.13 (.875)18.15±11.78 19.75±17.15 20.27±15.35 0.28 (.758)56.47±24.29 58.33±22.04 65.08±20.18 1.11 (.334)80.45±20.05 87.22±11.42 86.51±14.91 0.96 (.387)18.72±15.79 17.69±12.87 14.02±10.32 0.83 (.438) Education level≤Elementary school

Middle school ≥High school 53.95±16.82 64.29±20.44 53.37±20.75 2.72 (.070)82.91±14.59 82.22±14.41 83.00±13.82 0.02 (.977)17.23±11.19 18.75±14.31 20.43±13.53 0.78 (.461)60.46±16.98 65.74±28.87 51.67±28.28 2.58 (.081)86.37±13.96a 85.67±17.84a 74.05±22.90b

5.05 (.008) b<a

15.48±11.07a 12.89±13.28a 23.16±18.14b

4.13 (.019) b<a Employment statusEmployed Unemployed 62.50±20.35 53.44±18.41-0.22 (.028)87.71±10.93 81.33±14.75-2.48 (.016)15.41±10.89 19.59±12.961.55 (.124)64.29±22.69 56.75±23.57-1.31 (.193)85.44±17.57 81.00±19.30-0.96 (.342)15.34±14.62 18.33±14.800.84 (.412) Monthly income (10,000 won)≤100 >10054.84±19.16 56.70±19.38-515 (.608)82.17±15.57 83.87±11.68-636 (.526)18.78±12.94 18.36±12.140.18 (.860)61.16±22.93 53.73±23.941.55 (.125)84.09±17.22 78.40±12.251.47 (.146)16.10±13.70 20.31±16.14-1.39 (.168) ECOG PS0 1 2

82.05±18.27a 54.49±16.12b 40.10±14.98b

24.83 (<.001) b<a

89.31±09.25a 83.26±13.75ab 75.04±17.01b

4.01 (.021) b<a

13.77±12.78 19.03±12.19 20.18±14.03 1.14 (.324)73.61±14.58a 58.12±23.60a 41.67±20.41b

5.53 (.005) b<a

92.67±07.99a 82.62±18.78a 63.67±18.10b

7.49 (.001) b<a

10.08±08.66a 17.69±15.16ab 26.68±12.57b

3.78 (.026) b<a Comorbid disease Yes No 57.99±19.39 58.37±18.99-1.16 (.249)85.11±11.40 81.24±15.70-1.56 (.121)16.39±11.74 20.15±13.011.62 (.108)58.14±22.58 58.48±24.310.07 (.943)80.85±19.99 82.71±18.300.48 (.630)18.74±14.72 16.95±14.84-0.60 (.553) Primary site of tumorEsophagus Stomach Colon and rectum Liver, pancreas, and bile duct

65.00±14.90 54.17±19.97 55.83±20.86 55.23±17.63 0.46 (.710)82.53±12.27 83.78±13.12 83.08±14.64 82.82±14.17 0.11 (.953)20.50±12.26 20.68±11.06 15.68±10.76 19.59±14.98 1.14 (.336)68.75±23.94 54.46±29.26 60.48±20.94 58.08±20.78 0.61 (.612)89.17±10.63 75.07±23.39 84.00±18.25 84.68±14.99 1.83 (.146)15.28±17.44 19.73±17.62 14.94±11.76 19.21±14.83

0.73 (.535) Anticancer therapyChemotherapy Chemotherapy and radiotherapy

55.48±19.20 58.33±22.04-0.25 (.801)82.64±14.30 89.89±03.89-0.87 (.384)18.76±12.70 13.17±05.870.76 (.450)58.33±23.45 58.33±35.360.00 (>.999)81.84±19.05 86.34±17.44-0.33 (.742)17.60±14.65 22.84±25.31-0.50 (.621) ECOG PS=Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status.

4. Factors predictive of QOL

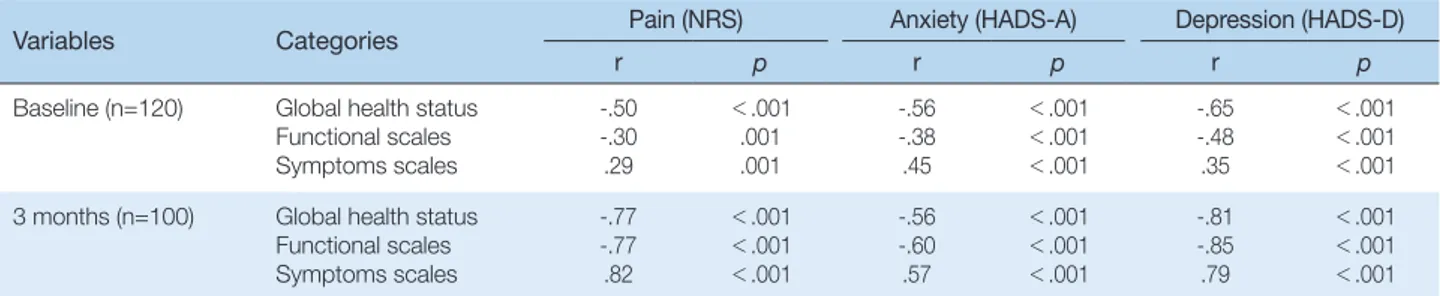

The predictive factors for QOL at baseline and at 3 months are listed in Table 5. At baseline, depression, ECOG PS, and anxiety accounted for 55.0% (adjusted R2= 0.55, p<.001) of the variance in EORTC QLQ-C30 global health status score, depression accounted for 22.0% (adjusted R2= 0.22, p<.001) of the variance in EORTC QLQ-C30 functional scales score, and anxiety accounted for 19.0% (adjusted R2= 0.19, p<.001) of the variance in EORTC QLQ-C30 symptom scales score. At 3 months, depression, pain, and ECOG PS accounted for 72.0% (ad- justed R2= 0.72, p<.001) of the variance in EORTC QLQ-C30 global health status score, 76.0% (adjusted R2= 0.76, p<.001) of the variance in EORTC QLQ-C30 functional scales score, and 74.0% (adjusted R2= 0.74, At both baseline and 3 months there were negative correlations be-

tween EORTC QLQ-C30 global health status score and pain, anxiety, and depression; negative correlations between EORTC QLQ-C30 func- tional scales score and pain, anxiety, and depression; and positive corre- lations between EORTC QLQ-C30 symptom scales score and pain, anxiety, and depression (Table 4). The strength of the correlations be- tween QOL and pain, anxiety, and depression were greater at 3 months than at baseline. At both time points, the strength of the correlation be- tween QOL and depression was stronger than that between QOL and anxiety, with the exception of the symptoms dimension of QOL (EORTC QLQ-C30 symptom scales score) at baseline.

Table 4. Correlations between Quality of Life and Pain, Anxiety, and Depression

Variables Categories Pain (NRS) Anxiety (HADS-A) Depression (HADS-D)

r p r p r p

Baseline (n=120) Global health status Functional scales Symptoms scales

-.50 -.30 .29

<.001 .001 .001

-.56 -.38 .45

<.001

<.001

<.001

-.65 -.48 .35

<.001

<.001

<.001 3 months (n=100) Global health status

Functional scales Symptoms scales

-.77 -.77 .82

<.001

<.001

<.001

-.56 -.60 .57

<.001

<.001

<.001

-.81 -.85 .79

<.001

<.001

<.001 EORTC QLQ-C30= European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer quality of life questionnaire-core 30; NRS= Numeric rating scale; HADS- A= Hospital anxiety and depression scale-anxiety; HADS-D= Hospital anxiety and depression scale-depression.

Table 5. Predictive Factors for Quality of Life

Variables Categories QOL (EORTC QLQ-C30)

B SE ß t p Adjusted R2 F p

Baseline (n=120)

Global health status

(Constant) Depression ECOG PS Anxiety

96.84 -1.83 -12.65 -2.17

5.04 0.49 2.76 0.48

19.22 -0.31 -0.33 -0.34

19.22 -3.75 -4.59 -4.53

<.001

<.001

<.001

<.001

.42 .48 .55

49.60 <.001

Functional scales (Constant) Depression

94.12 -2.06

2.23 0.35

-0.48 42.27 -5.91

<.001

<.001 .22

34.92 <.001

Symptom scales (Constant) Anxiety

13.74 1.88

1.38 0.35

0.45 9.96

5.40 <.001

<.001 .19

29.14 <.001

3 months (n=100)

Global health status

(Constant) Depression Pain ECOG PS

94.36 -2.52 -5.08 -7.86

5.38 0.45 1.14 2.72

-0.48 -0.37 -0.16

17.55 -5.63 -4.45 -2.89

<.001

<.001

<.001 .005

.66 .70 .72

87.49 <.001

Functional scales (Constant) Depression ECOG PS Pain

114.14 -2.63 -7.03 -2.59

4.03 0.34 2.04 0.86

-0.63 -0.18 -0.24

28.29 -7.82 -3.44 -3.02

<.001

<.001 .001 .003

.72 .74 .76

106.30 <.001

Symptom scales (Constant) Pain Depression ECOG PS

-1.37 4.58 1.13 3.69

3.28 0.70 0.27 1.66

0.54 0.35 0.12

1.70 6.58 4.14 2.22

<.001

<.001

<.001 .029

.67 .73 .74

94.71 <.001

QOL= Quality of life; EORTC QLQ-C30= European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer quality of life questionnaire-core 30; ECOG PS= Eastern Cooperative Oncol- ogy Group performance status.

most common tumor type23) and patients with esophageal cancer com- monly experience symptomatic problems caused by dysphagia, nausea, vomiting, and pain. The objective of this study was to assess the factors associated with QOL at initial diagnosis of advanced cancer and during the palliative treatment process. There was no significant change in QOL between baseline and 3 months in patients with advanced gastro- intestinal cancer. It is possible that only patients with advanced or meta- static gastrointestinal cancer requiring palliative chemotherapy were in- cluded, but all included patients had good PS (ECOG PS≤2). However, psychologic symptoms, such as anxiety or depression, were significant predictors of QOL in patients with advanced gastrointestinal caner. Fur- thermore, psychological symptoms associated with QOL changed be- fore and after treatment; anxiety was a significant predictive factor of QOL at baseline and depression was a significant predictive factor of QOL at both baseline and 3 months. In the present study, 37 (30.8%) of the 120 patients at baseline were identified as having anxiety or depres- sion according to HADS, which is consistent the results reported in a previous study of Korean cancer patients at all cancer stages and with all cancer types.26) The mean HADS anxiety score decreased from 2.60 points at baseline to 2.30 points at 3 months, and the mean HADS de- pression score increased from 5.49 points at baseline to 5.86 points at 3 months, although there were no statistically significant changes in anxi- ety or depression between baseline and at 3 months. Gil et al12) also re- ported that anxiety decreased and depression increased from pre to post cancer treatment. The emotional impact of learning of a cancer diagno- sis may explain the high level of anxiety immediately after diagnosis.

With the progression of the treatment, patients may become more aware of the significance of the cancer diagnosis, and this is likely followed by an increased awareness of the effects of the disease on all aspects of life.

This may lead to patients becoming more depressed. In patients with advanced cancer requiring palliative therapy, there is a gradual increase in uncomfortable somatic symptoms, and this is accompanied by diffi- culties associated with treatment procedures such as chemotherapy. This may also contribute to an increase in depressive symptoms.

Pain is one of the most common symptoms in cancer patients, and significantly affects the functional status and QOL of cancer pa- tients.28,29) In a previous study of patients with gastrointestinal cancer, the presence of cancer pain was associated with a higher prevalence of depression and a lower QOL (global health status), role and emotional functioning.18) The incidence of cancer pain in the present study was much lower (38% at baseline and 54.2% at 3 months) than in previous p<.001) of the variance in EORTC QLQ-C30 symptom scales score.

Depression and ECOG PS were significant predictors of QOL at base- line and 3 months, anxiety was a significant predictor of QOL at base- line, and pain was a significant predictor of QOL at 3 months.

DISCUSSION

No previous study has reported relationship between psychological distress and QOL in Korean patients with advanced gastrointestinal cancer, despite the incidence of gastrointestinal cancer has a higher inci- dence than other cancers in Korea. The aim of this prospective study was to assess the factors that are associated with QOL in Korean patients with advanced gastrointestinal cancer requiring palliative chemotherapy at initial diagnosis of advanced cancer and during the palliative treat- ment process and to determine whether anxiety and depression are pre- dictive of QOL. In the present study, we found that anxiety, depression, ECOG PS, and pain were predictive of QOL, and the factors that were predictive of QOL were different at initial diagnosis of advanced cancer and after 3 months of treatment. Depression and PS were significant predictive factors of QOL at both baseline and 3 months, and anxiety and pain were significant predictive factors of QOL at baseline and 3 months, respectively. Our results provide baseline data for the develop- ment of psychological interventions adapted according to the time since initial diagnosis for the improvement of QOL in patients with advanced gastrointestinal cancer.

There is accumulating evidence of an association between psychologi- cal distress and QOL in cancer patients.14-18) In Korea, the prevalence of anxiety or depression in cancer patients has been estimated as 28.8~56.5% when all stages and cancer types are considered.25,26) How- ever, there are few studies that have focused on anxiety and depression in patients with gastrointestinal cancer, or that have reported an associa- tion between psychological distress and QOL in patients with gastroin- testinal cancer.19,20,27) Alacacioglu et al20) reported that anxiety and de- pression were strongly associated with poor QOL in Turkish colorectal cancer patients, and Tsunoda et al27) reported that depression had a stronger impact than anxiety on the global QOL of colorectal cancer pa- tients. In the present study, participants reported a moderate level of QOL. This is consistent with a previous study of patients with advanced colorectal cancer,20) but symptom QOL in our study was much lower (indicating better QOL) than that reported in a study of patients with metastatic gastrointestincal cancer,23) because esophageal cancer was the

REFERENCES

1. National Cancer Institute. Surveillance, epidemiology, and end results program. http://seer.cancer.gov. Assessed November 28, 2016.

2. Oh CM, Won YJ, Jung KW, Kong HJ, Cho H, Lee JK, et al. Community of population-based regional cancer registries. Cancer statistics in Ko- rea: incidence, mortality, survival, and prevalence in 2013. Cancer Res Treat. 2016;48(2):436-50.

3. Jung KW, Won YJ, Oh CM, Kong HJ, Cho H, Lee JK, et al. Prediction of cancer incidence and mortality in Korea, 2016. Cancer Res Treat. 2016;

48(2):451-7.

4. National Cancer Information Center. Cancer Statistics in Korea. http://

www.cancer.go.kr. Assessed November 28, 2016.

5. Polanski J, Jankowska-Polanska B, Rosinczuk J, Chabowski M, Szyman- ska-Chabowska A. Quality of life of patients with lung cancer. Onco Targets Ther. 2016;9:1023-8.

6. van Nieuwenhuizen AJ, Buffart LM, Brug J, Leemans CR, Verdonck-de Leeuw IM. The association between health related quality of life and survival in patients with head and neck cancer: a systematic review. Oral Oncol. 2015;51(1):1-11.

7. Svensson H, Hatschek T, Johansson H, Einbeigi Z, Brandberg Y. Health- related quality of life as prognostic factor for response, progression-free survival, and survival in women with metastatic breast cancer. Med Oncol. 2012;29(2):432-8.

8. Temel JS, Greer JA, Muzikansky A, Gallagher ER, Admane S, Jackson VA, et al. Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(8):733-42.

9. Pirl WF, Greer JA, Traeger L, Jackson V, Lennes IT, Gallagher ER, et al.

Depression and survival in metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer: ef- fects of early palliative care. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(12):1310-5.

10. Giese-Davis J, Collie K, Rancourt KM, Neri E, Kraemer HC, Spiegel D.

Decrease in depression symptoms is associated with longer survival in patients with metastatic breast cancer: a secondary analysis. J Clin On- col. 2011;29(4):413-20.

11. Pinquart M, Duberstein PR. Depression and cancer mortality: a meta- analysis. Psychol Med. 2010;40(11):1797-810.

12. Gil F, Costa G, Hilker I, Benito L. First anxiety, afterwards depression:

psychological distress in cancer patients at diagnosis and after medical treatment. Stress Health. 2012;28(5):362-7.

13. Annunziata MA, Muzzatti B, Bidoli E. Psychological distress and needs of cancer patients: a prospective comparison between the diagnostic and the therapeutic phase. Support Care Cancer. 2010;19(2):291-5.

14. Andersen BL, DeRubeis RJ, Berman BS, Gruman J, Champion VL, Massie MJ, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology. Screening, as- sessment, and care of anxiety and depressive symptoms in adults with cancer: an American Society of Clinical Oncology guideline adapta- tion. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(15):1605-19.

15. Bužgová R, Jarošová D, Hajnová E. Assessing anxiety and depression with respect to the quality of life in cancer inpatients receiving palliative care. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2015;19(6):667-72.

16. Montazeri A. Quality of life data as prognostic indicators of survival in cancer patients: an overview of the literature from 1982 to 2008. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2009;7:102.

studies conducted on patients with metastatic cancer (64~90%).28) Many previous studies have included inpatients with metastatic cancer or pa- tients with progressive cancer after the initial diagnosis of metastatic cancer.28) By contrast, the current study focused on patients who were initially diagnosed with advanced gastrointestinal cancer at the outpa- tient clinic. In the current study, cancer pain was significant predictive factor of all dimensions of QOL after 3 months of treatment, i.e., at the time when there is a gradual increase in pain associated with the adverse effects of cancer therapy, such as chemotherapy or progression of the cancer itself.

The present study has several limitations. First, we did not perform a comprehensive analysis of the effects of palliative therapy on somatic, emotional, social, and spiritual symptoms, even though the adverse ef- fects of cancer treatment and the response to cancer treatment have been associated with QOL.30) Second, we measured QOL only at the initial di- agnosis of advanced gastrointestinal cancer and 3 months after the ini- tial diagnosis. Other social and economic problems may reduce QOL after diagnosis of advanced cancer and during the course of the disease, and severe psychological distress and physical symptoms caused by the uncontrolled growth of the tumor may affect QOL in terminal cancer patients who have stopped active chemotherapy. We suggest that all can- cer patients should be screened periodically for QOL and psychological symptoms as part of standard cancer care from initial diagnosis to death. Lastly, the number of patients recruited to the study was small, meaning there was insufficient statistical power for detailed subgroup analyses, and all patients were from a single institution, making it diffi- cult to generalize our results.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, depression and performance status are key factors that need to be improved to efficiently improve QOL in patients with ad- vanced gastrointestinal cancer, regardless of the time relative to diagno- sis. Anxiety should be monitored in the early stage after a diagnosis of advanced cancer, and pain should be monitored in the later stage where there is a gradual increase in pain with the progression of the cancer and the adverse effects of cancer therapy become apparent. Therefore, sys- tematic assessments and comprehensive psychological interventions for anxiety and depression are required periodically for patients with ad- vanced gastrointestinal cancer.

anxiety and depression scale for Koreans-A comparison of normal, de- pressed and anxious groups. J Korean Neuropsychiatr Assoc. 1999;38 (2):289-96.

25. Shim EJ, Shin YW, Jeon HJ, Hahm BJ. Distress and its correlates in Ko- rean cancer patients: pilot use of the distress thermometer and the problem list. Psychooncology. 2008;17(6):548-55.

26. Kim SJ, Rha SY, Song SK, Namkoong K, Chung HC, Yoon SH, et al.

Prevalence and associated factors of psychological distress among Ko- rean cancer patients. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2011;33(3):246-52.

27. Tsunoda A, Nakao K, Hiratsuka K, Yasuda N, Shibusawa M, Kusano M.

Anxiety, depression and quality of life in colorectal cancer patients. Int J Clin Oncol. 2005;10(6):411-7.

28. van den Beuken-van Everdingen MH, de Rijke JM, Kessels AG, Schouten HC, van Kleef M, Patijn J. Prevalence of pain in patients with cancer: a systematic review of the past 40 years. Ann Oncol. 2007;18 (9):1437-49.

29. Green CR, Hart-Johnson T, Loeffler DR. Cancer-related chronic pain:

examining quality of life in diverse cancer survivors. Cancer. 2011;117 (9):1994-2003.

30. Tachi T, Teramachi H, Tanaka K, Asano S, Osawa T. The impact of out- patient chemotherapy-related adverse events on the quality of life of breast cancer patients. PLoS One. 2015;10(4):e0124169

17. Slovacek L, Slovackova B, Slanska I, Petera J, Priester P. Quality of life and depression among metastatic breast cancer patients. Med Oncol.

2010;27(3):958-9.

18. Tavoli A, Montazeri A, Roshan R, Tavoli Z, Melyani M. Deression and quality of life in cancer patients with and without pain: the role of pain beliefs. BMC Cancer. 2008;8:177.

19. Matsushita T, Matsushima E, Maruyama M. Psychological state, quality of life, and coping style in patients with digestive cancer. Gen Hosp Psy- chiatry. 2005;27(2):125-32.

20. Alacacioglu A, Binicier O, Gungor O, Oztop I, Dirioz M, Yilmaz U.

Quality of life, anxiety, and depression in Turkish colorectal cancer pa- tients. Support Care Cancer. 2010;18(4):417-21.

21. Oken MM, Creech RH, Tormey DC, Horton J, Davis TE, McFadden ET, et al. Toxicity and response criteria of the Eastern Cooperative On- cology Group. Am J Clin Oncol. 1982;5(6):649-55.

22. Yun YH, Park YS, Lee ES, Bang SM, Heo DS, Park SY, et al. Validation of the Korean version of the EORTC QLQ-C30. Qual Life Res. 2004;13 (4):863-8.

23. Fard JH, Janbabaei G. Quality of life and its related factors among Ira- nian patients with metastatic gastrointestinal tract cancer: a cross-sec- tional study. Indian J Palliat Care. 2014;20(3):215-9.

24. Oh SM, Min KJ, Park DB. A study on the standardization of the hospital