Copyrights © 2015 by The Korean Gastric Cancer Association www.jgc-online.org This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (http://creativecommons.org/

licenses/by-nc/4.0) which permits unrestricted noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Introduction

According to GLOBOCAN 2012, gastric cancer is the fifth most common malignancy and the third most common cause of

cancer death worldwide.1 Although endoscopic resection, che- motherapy, and radiotherapy have improved,2-5 surgery remains the most important treatment strategy for gastric cancer. Complete surgical resection of tumors with en block lymphadenectomy provides a chance of cure for many patients with gastric cancer.3

Since Kitano et al.6 reported the first case of laparoscopic gastrectomy (LG) for gastric cancer; LG has gained popularity for early stage gastric cancer, especially in Korea and Japan. LG has several advantages over conventional open total gastrectomy (OTG), including less pain, better cosmetic results, shorter hos- pital stay, faster postoperative recovery, earlier return to normal activities of daily living, and a better quality of life.7-11 LG was initially limited to clinically early gastric cancer (EGC) located Correspondence to: Ji Yeong An

Department of Surgery, Yonsei University College of Medicine, 50-1 Yonsei-ro, Seodaemun-gu, Seoul 03722, Korea

Department of Surgery, Samsung Medical Center, Sungkyunkwan University School of Medicine, 81 Irwon-ro, Gangnam-gu, Seoul 06351, Korea

Tel: +82-2-3410-0498, Fax: +82-2-313-6981 E-mail: ugids@naver.com

Received June 27, 2015 Revised August 25, 2015 Accepted August 25, 2015

*These authors contributed equally to this paper as co-first authors.

Short-Term Outcomes of Laparoscopic Total Gastrectomy Performed by a Single Surgeon Experienced in

Open Gastrectomy: Review of Initial Experience

Jeong Ho Song1,*, Yoon Young Choi1,*, Ji Yeong An1,4, Dong Wook Kim2, Woo Jin Hyung1, and Sung Hoon Noh1,3

1Department of Surgery, 2Biostatistics Collaboration Unit,

3Brain Korea 21 PLUS Project for Medical Science, Yonsei University Health System, Yonsei University College of Medicine,

4Department of Surgery, Samsung Medical Center, Sungkyunkwan University School of Medicine, Seoul, Korea

Purpose: Laparoscopic total gastrectomy (LTG) is more complicated than laparoscopic distal gastrectomy, especially during a surgeon’s initial experience with the technique. In this study, we evaluated the short-term outcomes of and learning curve for LTG during the initial cases of a single surgeon compared with those of open total gastrectomy (OTG).

Materials and Methods: Between 2009 and 2013, 134 OTG and 74 LTG procedures were performed by a single surgeon who was experienced with OTG but new to performing LTG. Clinical characteristics, operative parameters, and short-term postoperative outcomes were compared between groups.

Results: Advanced gastric cancer and D2 lymph node dissection were more common in the OTG than LTG group. Although the opera- tion time was significantly longer for LTG than for OTG (175.7±43.1 minutes vs. 217.5±63.4 minutes), LTG seems to be slightly su- perior or similar to OTG in terms of postoperative recovery measures. The operation time moving average of 15 cases in the LTG group decreased gradually, and the curve flattened at 54 cases. The postoperative complication rate was similar for the two groups (11.9% vs.

13.5%). No anastomotic or stump leaks occurred.

Conclusions: Although LTG is technically difficult and operation time is longer for surgeons experienced in open surgery, it can be per- formed safely, even during a surgeon’s early experience with the technique. Considering the benefits of minimally invasive surgery, LTG is recommended for early gastric cancer.

Key Words: Stomach neoplasms, Laparoscopy, Total gastrectomy, Learning curve

Several studies have reported that laparoscopic distal gastrec- tomy (LDG) is both safe and feasible.13-16 Recent studies have shown that short-term outcomes of laparoscopic total gastrectomy (LTG) are comparable to those of conventional OTG.17-19 How- ever, LTG is likely to be more complicated than LDG, especially for less experienced surgeons, because it is difficult to perform an esophagojejunostomy and lymph node dissection around the splenic hilum and left paracardial areas. Nevertheless, few studies have provided information about the learning curve for LTG.20

In this study, we evaluated the short-term outcomes of the initial consecutive LTG cases performed by a single surgeon with substantial previous experience in performing OTG and used these cases to determine the learning curve for LTG.

Materials and Methods

1. Patients

We reviewed the data of 74 consecutive patients who under- went LTG performed by a single surgeon with curative intent between April 2009 and December 2013 at Severance Hospital.

The surgeon trained as a clinical fellow for 3 years at a gastric cancer specialized center where more than 1,000 cases of gastric cancer surgery were done annually, and had assisted on many cases of OTG and approximately 20 laparoscopic surgeries. In addition, laparoscopic surgery training in animal models was provided once a year. As such, at the time of the first case of LTG in this study, the surgeon already had experience perform- ing >100 cases of OTG and 15 cases of LDG. LTG was initially used only patients with early stage of gastric cancer; thereafter, the indication was expanded to cases of locally AGC. All data were collected prospectively in a unique database. Data were also reviewed for patients who underwent OTG for proximal gastric cancer during the same period by the same surgeon to provide reference data. This study was approved by Severance Hospital’s institutional review board (4-2014-0513).

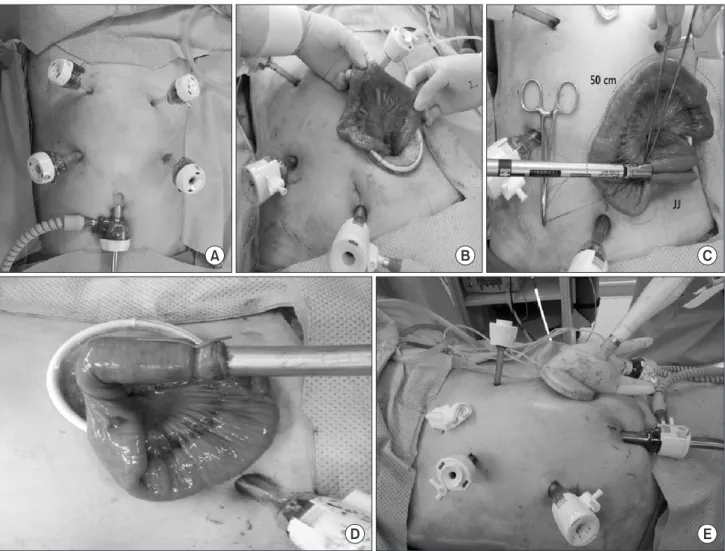

infra-umbilical incision using an open method. After pneumo- peritoneum was achieved, two 12-mm trocars were inserted in the right and left flank areas. Two 5-mm trocars were inserted in the right and left upper quadrants 2 cm below both lower rib margins. Laparoscopic coagulation shears (Ethicon, Cincinnati, OH, USA) were used for the lymph node dissection: D1+ or D2 lymph node dissection was performed for clinically EGC, while D2 lymph node dissection was conducted for advanced tumors (D2 lymph node dissection included splenic hilum lymph node dissection). The duodenum was resected below the pyloric ring via intracorporeal approach. After the esophagus was clamped, esophageal resection was performed between the two clamps using laparoscopic coagulation shears. A purse-string suture was created around the esophagus. The resected stomach was removed through a 4-cm mini-laparotomy incision that was formed by extending the incision for the 12-mm trocar in the lower left quadrant. A 25-mm detachable anvil was inserted in the esophageal stump and a purse-string suture was tied over the purse-string tying notch of the anvil. After a jejunojejunostomy was performed through the incision, esophagojejunostomy was conducted with a laparoscopic circular stapler EEA 25 (Covidien, Mansfield, MA, USA), and the jejunal stump was closed with a linear stapler (Fig. 1, Supplementary Video Clip). A closed drain tube was placed along the esophagojejunostomy site.

3. Evaluating postoperative outcomes

The clinical characteristics of the enrolled patients, includ- ing age, sex, American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) score, history of previous abdominal operation, body mass index (BMI), and tumor classification, were reviewed and compared between the two groups. Factors associated with perioperative outcomes, such as the lymph node dissection extent, presence of combined resection, operation time, intraoperative bleeding, hospital length of stay, time to first flatus, and time to first soft diet were reviewed.

To control postoperative pain, intravenous patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) was provided for patients who underwent LTG

and epidural PCA was given to those who underwent OTG. If the patient requested more analgesics, additional intravenous or intramuscular analgesics were supplied, and the number of ad- ditional doses during the first 7 postoperative days (POD) was recorded. To estimate pain severity after gastrectomy, visual analog scale (VAS) pain scores were recorded on POD 0 to 7. A white blood cell (WBC) count was obtained preoperatively, im- mediately after surgery (POD 0), and on POD 1, 3, and 5, while a serum C-reactive protein (CRP) level was obtained on POD 1, 3, and 5. Complications were recorded according to the Clavien- Dindo Classification of surgical complications.21

4. Statistical methods

IBM SPSS ver. 20.0 (IBM Co., Armonk, NY, USA) was used to analyze the demographics and perioperative outcomes of each

group. Pearson’s chi-square test was used to compare categori- cal variables. An independent t-test was used for continuous variables if the data for both groups satisfied the normality cri- teria; otherwise, Mann-Whitney’s U-test was used. To compare longitudinal outcomes, such as VAS pain scores, WBC counts, and serum CRP levels, a linear mixed model was applied, and the outcomes at each time were compared by independent t- tests. To describe the learning curve, the stable operation time was evaluated by the moving average method (‘nls2’) and non-linear regression model (‘bcp’ and ‘strucchange’) using R statistics ver- sion 2.12.1 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Aus- tria). Values of P<0.05 were considered statistically significant.

A B C

D E

Fig. 1. Trocar locations and extracorporeal procedures for laparoscopic total gastrectomy. (A) Trocar placement. (B) Small bowel extraction through a mini-laparotomy in the lower left quadrant of the abdomen. (C) Jejunojejunostomy (JJ) approximately 50 cm distal to the esophagojejunostomy site. (D) Circular stapler insertion into the jejunum to create the esophagojejunostomy. (E) Circular stapler with jejunum insertion into the intra- abdominal cavity for the esophagojejunostomy.

to have AGC than those in the LTG group (P=0.003 and <0.001, respectively).

2. Perioperative outcomes

Table 2 shows perioperative outcomes for each group. In the OTG group, 92.5% of patients underwent D2 lymph node dis- section; in contrast, D2 lymph node dissection was used for only 32.4% of the 74 patients in the LTG group, and fewer lymph nodes were retrieved in the LTG than OTG group (P=0.020).

The percentages of patients who underwent combined resection were similar for the two groups. The operation time was longer in the LTG group than in the OTG group (217.5 minutes vs.

analgesic doses were required during the first 7 POD in the LTG group, but the overall pain scores during the first 7 days after

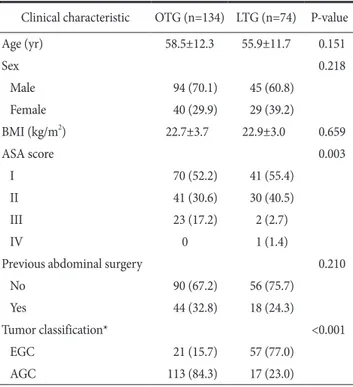

Table 1. Patients’ clinical characteristics

Clinical characteristic OTG (n=134) LTG (n=74) P-value

Age (yr) 58.5±12.3 55.9±11.7 0.151

Sex 0.218

Male 94 (70.1) 45 (60.8)

Female 40 (29.9) 29 (39.2)

BMI (kg/m2) 22.7±3.7 22.9±3.0 0.659

ASA score 0.003

I 70 (52.2) 41 (55.4)

II 41 (30.6) 30 (40.5)

III 23 (17.2) 2 (2.7)

IV 0 1 (1.4)

Previous abdominal surgery 0.210

No 90 (67.2) 56 (75.7)

Yes 44 (32.8) 18 (24.3)

Tumor classification* <0.001

EGC 21 (15.7) 57 (77.0)

AGC 113 (84.3) 17 (23.0)

Values are presented as mean±standard deviation or number (%). OTG = open total gastrectomy; LTG = laparoscopic total gastrectomy; BMI = body mass index; ASA = American Society of Anesthesiologists; EGC

= early gastric cancer; AGC = advanced gastric cancer. *Classification according to the standard of Japanese Classification of Gastric Carcinoma 3rd English edition on gastric cancer staging system.

Table 2. Operative and postoperative outcomes of OTG and LTG

Variable OTG

(n=134) LTG

(n=74) P-value Extent of lymph node dissection*

D1+b

D2 10 (7.5)

124 (92.5) 50 (67.6) 24 (32.4)

<0.001

No. of retrieved lymph node 44.8±18.2 39.9±11.8 0.020 Combined resection 29 (21.6) 11 (14.9) 0.273 Operation time (min) 175.7±43.1 217.5±63.4 <0.001 Intraoperative blood loss (g) 130.0±126.5 80.8±60.4 <0.001 Hospital stay after surgery (d) 9.0±3.1 8.3±3.4 0.097 First flatus passage (d) 3.8±0.8 3.5±0.7 <0.001 Soft diet initiated (d) 6.0±1.9 5.7±2.0 0.252 No. of additional pain killers used

for POD 7 7.7±5.8 4.7±4.0 <0.001

VAS POD 0 POD 1 POD 2 POD 3 POD 4 POD 5 POD 6 POD 7

5.4±2.0 5.6±2.1 5.9±1.8 5.5±1.9 4.5±2.0 4.0±1.9 3.5±1.9 2.9±1.7

5.5±1.9 4.8±1.9 4.8±1.9 4.5±1.8 3.8±1.9 3.7±1.9 3.0±1.6 2.7±1.5

0.873 0.850 0.010

<0.001 0.001 0.012 0.254 0.056 0.513 WBC Preoperative

POD 0 POD 1 POD 3 POD 5

6.5±2.3 12.6±4.5 10.9±3.3 7.5±3.0 6.4±2.1

6.5±1.9 14.0±3.1 11.1±3.2 7.2±2.4 6.6±2.0

0.521 0.881 0.007 0.709 0.454 0.542 Serum C-reactive protein (mg/ml)

POD 1 POD 3 POD 5

56.2±31.6 101.6±58.1 60.2±50.6

63.4±27.6 98.5±59.3 57.4±51.0

0.202 0.103 0.721 0.717 Values are presented as number (%) or mean±standard deviation.

OTG = open total gastrectomy; LTG = laparoscopic total gastrectomy;

POD = postoperative day; VAS = visual analogue scale; WBC = white blood cell. *Classification according to the Japanese gastric cancer treatment guidelines 2010 (ver. 3).

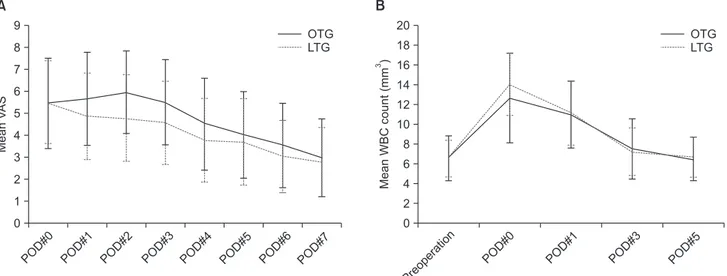

gastrectomy did not differ between the two groups (Table 2, Fig. 2A). Inflammatory markers such as WBC counts and serum CRP levels were generally similar between the two groups. Ex- cept for a higher WBC in the LTG group on the day of surgery (P=0.007), the WBC and CRP levels did not differ significantly between groups (Table 2, Fig. 2B).

3. Postoperative morbidities

Postoperative morbidities occurred in 10 of the 74 patients (13.5%) in the LTG group and 16 of the 134 patients (11.9%) in the OTG group (Table 3). The morbidities in the LTG group included grade II intra-abdominal complicated fluid collection (n=4), hematoma (n=2), respiratory complication (n=1), and cellulitis controlled by antibiotics (n=1). The morbidities in the OTG group included wound infection (n=2), intra-abdominal

complicated fluid collection (n=4), respiratory complication (n=2), and deep vein thrombosis (n=1). Two patients in the OTG group required postoperative external drainage for their compli- cated intra-abdominal fluid collection; these cases were graded as III-a complications. There were no cases of anastomotic or stump leaks in either group.

4. Learning curve

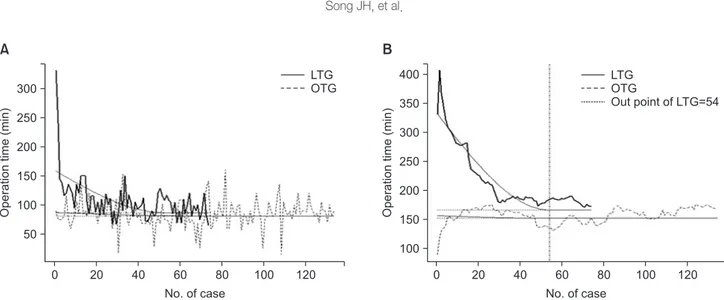

To determine the learning curve for LTG, the operation time was evaluated using the moving average method. Fig. 3A shows that the operation time for LTG cases gradually decreased after the first case, whereas the operation time for OTG cases per- formed in the same period as the LTG cases exhibited no overall decrease (each point represents the operative time of each case, the lines represent its serial pattern in LTG and OTG, and the A

MeanVAS

POD#0 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 0

POD#1 POD#2 POD#3 POD#4 POD#5 POD#6 POD#7

MeanWBCcount(mm)3

Preoperatio n 20 18 16 14 12 10 8 6 4 2 0

POD#0 POD#1 POD#3 POD#5

OTG LTG OTG

LTG

B

Fig. 2. Mean visual analog scale (VAS) scores (A) and white blood cell (WBC) counts (B) after laparoscopic total gastrectomy (LTG) and open total gastrectomy (OTG). POD = postoperative day.

Table 3. Postoperative complications after OTG and LTG

Grade* OTG (n=134) LTG (n=74) P-value

Grade I Wound problem (n=2)

Chylous ascites (n=3) Wound problem (n=2)

Hematochezia (n=1) -

Grade II Wound infection (n=2)

Intra-abdominal complicated fluid collection (n=4) Respiratory problem (n=2)

Leg DVT (n=1)

Intra-abdominal complicated fluid collection (n=4) Intra-abdominal hematoma (n=1)

Respiratory problem (n=1) Cellulitis (n=1)

-

Grade III-a Complicated fluid collection (n=2) - -

Total (n) 16 (11.9%) 10 (13.5%) 0.660

OTG = open total gastrectomy; LTG = laparoscopic total gastrectomy; DVT, deep vein thrombosis. *Classification according to the Clavien-Dindo classification.

curved line is the trend line). Fig. 3B is a graph of the consecu- tive 15 cases that shows its average sequentially through the moving average method. The operation time moving average of 15 cases in the LTG group decreased gradually, and the curve converged to a flat line after 54 cases as analyzed by the non- linear regression model. In the OTG group, a cut-off point could not be calculated, and it converged from its initial case because the surgeon was already past the learning curve (Fig. 3B). Over- all morbidity in the pre- versus post-learning curve of LTG was not statistically different (13.0% and 15.0% in pre- and post- learning curve, respectively, Fisher’s exact test; P=0.543)

Discussion

Although the benefits of LTG in gastric cancer surgery are widely accepted, technical difficulty is one of the main reasons surgeons may be reluctant to perform it. Especially for surgeons experienced with OTG, starting to perform LTG can be ac- companied by a longer operation time and the potential risk of surgical complications. Therefore, here we analyzed the initial experience with LTG of a single surgeon who was previously experienced with OTG. As shown by our results, LTG can be performed safely, even during a surgeon’s initial use of the tech- nique, and 54 cases are necessary to overcome the learning curve as assessed by operation time.

The technical steps for laparoscopic esophagojejunostomy are shown in Fig. 1 and the Supplementary Video Clip. Resected stomach extirpation, anvil insertion, jejunojejunostomy creation, and circular stapler insertion were performed through a mini-

laparotomy in the lower left quadrant. Some surgeons recently used a linear stapler for esophagojejunostomy,22 which can be in- serted through a 12-mm trocar without the need for an additional incision. Although using a linear stapler for esophagojejunostomy can avoid a mini-laparotomy, we used a circular stapler both be- cause we were familiar with it and it is also used for OTG.

Postoperative morbidity and mortality are important fac- tors for assessing short-term surgical outcomes. We found that the complications incidence, type, and grade after gastrectomy were similar for OTG and LTG. No anastomotic or stump leaks and no mortality occurred after OTG or LTG, while no grade III complications occurred after LTG. Although the operation time was longer for LTG than OTG, all patients recovered safely without major complications. Admittedly, the differences in tumor characteristics (EGC vs. AGC) and the extent of lymph node dissection (D1+ vs. D2) between OTG and LTG may have influenced our results comparing short-term outcomes and operation-related factors between the two groups. Nevertheless, our data appear to demonstrate the technical safety of LTG.

Analysis of the operation time learning curve for LTG showed that it converged to a flat line after 54 cases. Comparing our results to previous reports of the learning curve for LDG for gastric cancer,23 more experience seems to be required to per- form LTG. In this study, the surgeon had adequate experience with OTG before starting to perform LTG. Thus, the operation time was significantly shorter for OTG than for LTG and there was no learning curve for OTG. Because LTG was usually per- formed for clinical EGC, D1+ lymph node dissection was more common used than D2 dissection during LTG. To ensure an

50

0 20 40 60 80 100 120

No. of case

100

0 20 40 60 80 100 120

No. of case

Fig. 3. Operation time and learning curves for laparoscopic total gastrectomy (LTG) and open total gastrectomy (OTG). (A) Changes in operation time with the accumulation of case experiences. (B) A graph of the consecutive 15 cases showing its sequential average through the moving average method.

adequate D2 lymph node dissection, including hilar lymph node dissection, more experience with LTG would be necessary.

Although postoperative complications and overall recovery were similar between the LTG and OTG groups, LTG showed the benefits of being a minimally invasive surgery, such as less blood loss, shorter time to first flatus, less pain, and less analgesic use. Therefore, LTG is a good surgical option for upper-third EGC, and if surgeons follow basic surgical principles for gastric cancer surgery, they can perform LTG safely, even during their initial experience with the technique.

Our study had limitations. Because it was a retrospective co- hort study, the tumor characteristics and lymph node dissection extent differed between the LTG and OTG groups. In addition, we did not analyze the oncological outcomes of LTG and only discussed the technical safety of LTG because the indications for LTG and OTG are different. The oncological safety of LTG in AGC would be another issue that could be addressed in future studies. Moreover, the learning curve for LTG for a completely novice surgeon is unknown because the surgeon in this study had already performed more than 100 OTG and 15 LDG pro- cedures. Moreover, during the learning curve period of LTG, the initial 54 cases here, the surgeon performed LDG more than four times more commonly than LTG. Experience with LDG can contribute to the surgeon overcoming the learning curve of LTG. If no case of LDG is accompanied, the number of proce- dures required to overcome the LTG learning curve would be greatly increased. The changed indication of LTG from EGC to AGC is another limitation.

In conclusion, LTG was safely and feasibly performed here by a surgeon experienced with OTG with comparable outcomes.

The learning curve of LTG for a surgeon experienced with OTG seemed to exceed 50 cases.

Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

Electronic Supplementary Material

This online version of this article (doi: 10.5230/jgc.2015.

15.3.159) contains supplementary materials.

References

1. Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Dikshit R, Eser S, Mathers C, Rebelo M, et al. Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: sources, methods and major patterns in GLOBOCAN 2012. Int J Can- cer 2015;136:E359-E386.

2. Chua YJ, Cunningham D. The UK NCRI MAGIC trial of peri- operative chemotherapy in resectable gastric cancer: implica- tions for clinical practice. Ann Surg Oncol 2007;14:2687-2690.

3. Nakajima T. Gastric cancer treatment guidelines in Japan. Gas- tric Cancer 2002;5:1-5.

4. Bang YJ, Kim YW, Yang HK, Chung HC, Park YK, Lee KH, et al; CLASSIC trial investigators. Adjuvant capecitabine and oxaliplatin for gastric cancer after D2 gastrectomy (CLAS- SIC): a phase 3 open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2012;379:315-321.

5. Songun I, Putter H, Kranenbarg EM, Sasako M, van de Velde CJ. Surgical treatment of gastric cancer: 15-year follow-up re- sults of the randomised nationwide Dutch D1D2 trial. Lancet Oncol 2010;11:439-449.

6. Kitano S, Iso Y, Moriyama M, Sugimachi K. Laparoscopy-as- sisted Billroth I gastrectomy. Surg Laparosc Endosc 1994;4:146- 148.

7. Chen K, Xu XW, Zhang RC, Pan Y, Wu D, Mou YP. Systematic review and meta-analysis of laparoscopy-assisted and open total gastrectomy for gastric cancer. World J Gastroenterol 2013;19:5365-5376.

8. Lee JH, Han HS, Lee JH. A prospective randomized study comparing open vs laparoscopy-assisted distal gastrectomy in early gastric cancer: early results. Surg Endosc 2005;19:168- 173.

9. Cui M, Xing JD, Yang W, Ma YY, Yao ZD, Zhang N, et al. D2 dissection in laparoscopic and open gastrectomy for gastric cancer. World J Gastroenterol 2012;18:833-839.

10. Zhao Y, Yu P, Hao Y, Qian F, Tang B, Shi Y, et al. Comparison of outcomes for laparoscopically assisted and open radical dis- tal gastrectomy with lymphadenectomy for advanced gastric cancer. Surg Endosc 2011;25:2960-2966.

11. Kim HH, Hyung WJ, Cho GS, Kim MC, Han SU, Kim W, et al. Morbidity and mortality of laparoscopic gastrectomy versus open gastrectomy for gastric cancer: an interim report: a phase III multicenter, prospective, randomized Trial (KLASS Trial).

Ann Surg 2010;251:417-420.

12. Kim HH, Han SU, Kim MC, Hyung WJ, Kim W, Lee HJ, et

tomy in gastric cancer: a comparative study with laparoscopy- assisted distal gastrectomy. J Surg Oncol 2009;100:392-395.

15. Shinohara T, Kanaya S, Taniguchi K, Fujita T, Yanaga K, Uyama I. Laparoscopic total gastrectomy with D2 lymph node dissection for gastric cancer. Arch Surg 2009;144:1138-1142.

16. Wada N, Kurokawa Y, Takiguchi S, Takahashi T, Yamasaki M, Miyata H, et al. Feasibility of laparoscopy-assisted total gas- trectomy in patients with clinical stage I gastric cancer. Gastric Cancer 2014;17:137-140.

17. Wang W, Li Z, Tang J, Wang M, Wang B, Xu Z. Laparo- scopic versus open total gastrectomy with D2 dissection for gastric cancer: a meta-analysis. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 2013;139:1721-1734.

18. Sakuramoto S, Kikuchi S, Futawatari N, Katada N, Moriya H, Hirai K, et al. Laparoscopy-assisted pancreas- and spleen-

Oncol 2014;21:2994-3001.

21. Clavien PA, Barkun J, de Oliveira ML, Vauthey JN, Dindo D, Schulick RD, et al. The Clavien-Dindo classification of surgical complications: five-year experience. Ann Surg 2009;250:187- 196.

22. Morimoto M, Kitagami H, Hayakawa T, Tanaka M, Matsuo Y, Takeyama H. The overlap method is a safe and feasible for esophagojejunostomy after laparoscopic-assisted total gastrec- tomy. World J Surg Oncol 2014;12:392.

23. Zhou D, Quan Z, Wang J, Zhao M, Yang Y. Laparoscopic- assisted versus open distal gastrectomy with D2 lymph node resection for advanced gastric cancer: effect of learning curve on short-term outcomes. a meta-analysis. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A 2014;24:139-150.