Effect of Ripening Conditions on the Quality and Storability of Muskmelon (Cucumis melo L.) Fruits

전체 글

(2) Effect of Ripening Conditions on the Quality and Storability of Muskmelon (Cucumis melo L.) Fruits. high-quality melon production since the 1990s, with an increase of the cultivation area (Park and Moon, 2004). Most melons vary in breeding and cultivation methods; netted melons and non-netted melons can be harvested within 50 to 55 days and 40 to 45 days after pollination respectively in Korea (Kim et al., 2007). After harvesting, the selection of the melon is based on the grade regulation of the National Agricultural Products Quality Management Service and mainly depends on size, net type, and stalk shape (Oh et al., 2011). Due to the climacteric nature of melon, fruit softening, sugar content, and aromatic components are expressed after ripening. Thus, it is important to harvest at the appropriate maturity stage and ripen melons at the proper temperature and humidity (Kim et al., 2010). It is difficult to choose well-ripened fruits that are ready for consumption due to the nature of the peel (thick and rough) and because the color of the fruit may not change even when the fruits ripen. According to Roe and Bruemmer (1981) and Robertson and Swinburne (1981), most of the harvested fruits continue ripening due to changes in polygalacturonase activity (PG) and pectin. The shelf life of melon is relatively short (7-10 days) at room temperature; excessive aging causes problems such as physiological changes, softening due to over-ripening, and odor production (Lester and Shellie, 1992). In addition, it is very difficult to determine even if the inside of the melon is decayed until the melon is cut (Choi et al., 2005). Living standards and income levels are improving, and consumer interest in quality products is increasing. However, most consumers do not purchase agricultural products directly from the producers. This means that consumers are not getting quality information regarding the fruits at the time of purchase, leading to a decrease in purchasing power (Kim et al., 2010). In this study, we investigated the ripening days of melons after harvesting and suggest the optimum days of ripening at 10°C and RT to obtain the best nutritional benefits of muskmelon fruits.. Materials and Methods Plant Material and Ripening Temperature ‘Honey One’ (Sejong Bio Co., Ltd) and ‘Earl`s Talent’ (NongWoo Bio Co., Ltd.) melon cultivars, which are commonly grown by farmers in Gangwon province, Republic of Korea, were seeded on 50 cell plastic trays on March 22, 2016. After 4 weeks, seedlings were transplanted in the Kangwon National University farm greenhouse to soil. Drip fertigation and the recommended standard growing practices were implemented throughout the growing period. Pollination was performed when the female flowers from the 11-13th stem nodes were ready for pollination and selection was made after 5 days of pollination to keep the better fruit. The growing tip was removed after the plants reached the 23-24th stem nodes. Fruits of ‘Honey One’ and ‘Earl's Talent’ were harvested at 37 ± 1 and 53 ± 1 days, respectively. After harvesting, the. fruits were transported directly to the postharvest laboratory and medium-sized (about 1.5 kg) fruits were selected based on the Agricultural Products Quality Management Administration Standard. The selected fruits were stored under conditions of 10°C (80 ± 5% RH) or room temperature 25°C (50 ± 5% RH). Data were collected at 3-day intervals for 21 days during the ripening period. Five fruits were kept at each condition for each sampling days. Weight loss, total soluble solids content (TSS), acidity, flesh firmness (1 cm from the peel), flesh firmness (2 cm from the peel), flesh and peel color, sugar content, specific gravity, pectin content, and PG activity were measured.. 742. Horticultural Science and Technology.

(3) Effect of Ripening Conditions on the Quality and Storability of Muskmelon (Cucumis melo L.) Fruits. Weight Loss and Respiration Rate Determination Fruits were weighed at the beginning of ripening for the initial weight measurement. Weight measurements were continued during each day of observation at 3-day intervals. The loss of weight was then calculated by subtracting each day’s observed fruit weight from the initial weight. Respiration rate of the melon fruits was measured as a function of CO2 concentration using the closed system method (Tilahun et al., 2018). The melon fruits were sealed in a 4.65 L airtight containers and allowed to stand at each ripening temperature for 3 h, then analyzed using a CO2 / O2 analyzer (CheckMate 9900, PBI Dansensor, Denmark) and measurements expressed as mL CO2/kg·h-1.. Changes in Ethylene, Acetaldehyde and Ethanol Production Rates During Ripening Melons were sealed in a 4.65 L airtight container at each ripening temperature (10°C and 25°C) for 3 h. After that, 1 mL of gas sample was drawn from each airtight container using a gas-tight syringe (Sangwanangkul et al., 2017) and injected into a gas chromatograph. Ethylene, acetaldehyde, and ethanol concentrations were measured using GC 2010 Shimadzu gas chromatograph (Shimadzu Corporation, Japan) equipped with BP 20 Wax column (30 m × 0.25 mm × 0.25 µm, SGE Analytical Science, Australia) and flame ionization detector (FID). The detector and injector were operated at 127°C and ovens at 50°C and carrier gas (N2) flow rate was 0.67 mL·s-1 (Park et al., 2000). Results were expressed as µL·kg-1·h-1.. Changes in Total Soluble Solids (TSS) and Titratable Acidity (TA) Total soluble solids (TSS) values were measured by digital refractometer (Atago Hand Refractometer N1, Japan) and results were expressed in °Brix. Titratable acidity was obtained by titrating diluted melon juice (1 mL juice: 19 mL distilled water) with 0.1 N NaOH up to pH 8.1 then analyzing samples with a DL22 Food and Beverage Analyzer (Mettler Toledo Korea Ltd.). The result was expressed in mg/100 g citric acid.. Changes in Sugar Content The sugar content was analyzed by using high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC; Waters Associates, Milford, MA, USA) through a refractive index (RI) detector (Waters 410 Differential Refractometer, Waters, Milford, MA, USA). The analytical column was a Sugar-PakTM1 column (6.5 × 300 mm, Waters, USA). The mobile phase was 100% distilled water and the flow rate was 0.5 mL·min-1 (Choi et al., 2001). 20 mL Distilled water was added to 2 g frozen melon sample and homogenized with a T25 Ultra-Turrax (IKA Korea. Ltd., Korea). The mixture was centrifuged at 2,000 rpm for 10 min with a HA-1000-3 centrifuge (Hanil Science Industrial Co., Ltd., Korea) and filtered through a 0.45 µm membrane filter. Samples (10 µL) were loaded into the HPLC in triplicate. The results were expressed by percentages as in Park et al. (2016). Sucrose, glucose, and fructose were used as standards (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO, USA).. Changes in Color Variables Melon peel and flesh color were read along their equatorial axes using a Chroma meter, model CR-400 (Minolta, Japan) with a standard white tile (L* = 97.79, a* = -0.38, b* = -2.05). The measured values were Hunter L*, a* and b*. Where. Horticultural Science and Technology. 743.

(4) Effect of Ripening Conditions on the Quality and Storability of Muskmelon (Cucumis melo L.) Fruits. L* indicates darkness to lightness; a* shows greenness to redness; and b* shows blueness to yellowness.. Firmness The melon fruits were cut into three equal parts and the firmness was measured at 1 cm and 2 cm from the peel. To determine the changes in firmness of melon during ripening period, measurements were done using a rheometer (Model compac-100, Japan). The pressure was applied in the vertical direction with a maximum force of 10 kg using a 3 mm diameter round stainless steel probe with a flat end. The results were expressed in newtons (N).. PG Activity and Pectin Content Enzyme Extraction and PG Activity. Distilled water was added to 5 g frozen melon sample and homogenized for 1 min. The mixture samples were stirred for 1 h using a mechanical stirrer. After filtration of the samples using Whatman filter paper No. 2, total volume was brought to 12 mL by adding distilled water and enzyme extraction was performed according to Hwang (1991). 0.2 mL of 0.5% polygalacturonase acid and 50 mM of sodium acetate buffer (pH 4.5) were added to 0.2 mL of enzyme solution and incubated at 37°C for 30 min. After adding 2 mL of 0.1 M borated buffer (pH 9.0) and 0.4 mL of 1% 2-cyanoacetamide, the mixture was vortexed and boiled at 100°C for 10 min (Gross, 1982). After cooling for 10 min, the absorbance at 276 nm was measured using a spectrophotometer (Thermo fisher scientific, Madison, WI 53711, USA). The standard curve was made by using polygalacturonic acid (Alfa Aesar Chemical Co., England). Ethanol Insoluble Solid (EIS). 80% ethanol was added to 5 g frozen melon flesh sample and homogenized. The mixture sample was boiled at 100°C in a water bath for 10 min then cooled to room temperature. The cooled sample was filtered with Mira cloth (Calbiochem, LaJolla, CA, USA) and the residue was washed with 10 mL 80% ethanol and 10 mL 100% acetone. The filtrate was then dried in a desiccator at 38°C and stored at room temperature for 10 min, following the methods of Kim et al. (2010). Soluble Pectin Fraction Extraction. 14 mL of distilled water was added to 0.1 g of EIS and the mixture was extracted at 30°C for 15 min. After filtration, the EIS was extracted twice in succession under the same conditions. The filtrate volume was adjusted to 50 mL by distilled water to obtain water soluble pectin (WSP). To the remaining WSP extract residue, 14 mL of 0.4% ammonium oxalate solution was added, and the residue repeatedly extracted three times at 30°C. The filtrate was adjusted to 50 mL by ammonium oxalate to obtain ammonium soluble pectin (ASP). Then, ASP extract residues were extracted twice with 20 mL 0.05 N hydrochloric acid at 85°C for 1 h. The filtrate was adjusted to 40 mL to obtain hydrochloric acid soluble pectin (HSP). Finally, HSP extracts residue were extracted three times with 14 mL of 0.05 N sodium hydroxide solution at 30°C for 15 min. The filtrate was adjusted to 50 mL to obtain sodium hydroxide soluble pectin (SSP) (Rouse et al., 1962; Manabe and Naohara; 1986; Zhang et al., 2007).. 744. Horticultural Science and Technology.

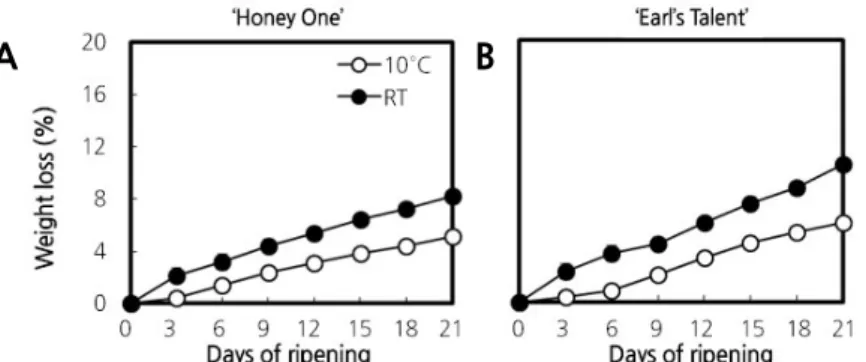

(5) Effect of Ripening Conditions on the Quality and Storability of Muskmelon (Cucumis melo L.) Fruits. Pectinase Enzyme Extraction. After soaking 0.2 g of EIS in 95% ethanol, 40 mL of 0.5% versene solution (5 g of ethylendiamine tetraacetic acid tetrasodium salt dissolved in 1 L of distilled water) was added. The pH was adjusted to 11.5 with 1 N NaOH solution and kept at 25°C for 30 min. The pH was lowered to 4.0 to 4.5 using acetic acid. Finally, 30 mg of pectinase was added to react for 1 h and used as an enzyme extract (McCready and McComb, 1952).. Quantification of Pectin. 1 mL each of fraction extract and enzyme extract were added to a glass tube using the methods followed by Blumenkrantz and Asboe-Hansen (1973) and Kintner PK and Van Buren JP (1982). The mixture was cooled in an ice water bath for 5 min, then 6 mL of a 12.5 mM H2SO4 / tetra borate solution (tetra borate dissolved in H2SO4) was added. The sample was then vortexed and boiled at 100°C for 5 min, immediately cooled in an ice water bath. After that, 0.1 mL of 0.5% NaOH solution was added for carbohydrate inhibition and 0.1 mL of 0.15% m-hydroxydipheyl solution was added for color development. After 30 min, the absorbance was measured at 520 nm using a UV-spectrophotometer (Thermo fisher scientific, Madison, USA). Standard curves were prepared using galacturonic acid monohydrate (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO, USA).. Sensory Evaluation Flavor, sweetness, chewiness, appearance and overall acceptability were evaluated by 9 people according to a subjective scale by Loizou (2011): 1 = bad, 2 = poor, 3 = fair, 4 = good, 5 = excellent.. Statistical Analysis Experiments were conducted in a completely randomized design with five replicates for TSS, TA, firmness (1 cm from the peel), firmness (2 cm from the peel), moisture of the stalk, specific gravity; and with three replicates for sugar content, PG activity, pectin content, weight loss. The results were analyzed using the SPSS (Version 23, SPSS, USA) for statistical analysis. Significant differences were tested using ANOVA, and Duncan’s multiple range test was used to determine which means were significantly different (p < 0.05).. Results and Discussion Changes in Weight Loss and Respiration Rate A significant difference in in melon characteristics (p < 0.05) was observed between ripening conditions for both ‘Honey One’ and ‘Earl`s Talent’ muskmelon cultivars. Both cultivars lost less weight when ripened at 10°C compared to RT. ‘Honey One’ showed a reduction of 3.08% and 5.39 % at 10°C and RT, respectively, on day 12 of ripening. ‘Earl`s Talent’ showed 3.41% and 6.06% reductions in weight (Fig. 1A and B) on day 12 at 10°C and RT, respectively. In general, the weight loss rate of fruit and vegetables is used as an indicator for determining the marketability of fruits and vegetables. Most fruit and vegetables lose marketability if the weight loss is more than 5% (Youn et al., 2009). In this study, both cultivars lost marketability after 18 d at 10°C and after 12 d at RT (Fig. 1). The weight loss at 10°C was likely. Horticultural Science and Technology. 745.

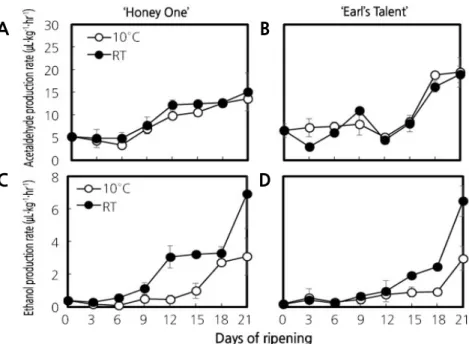

(6) Effect of Ripening Conditions on the Quality and Storability of Muskmelon (Cucumis melo L.) Fruits. A. B. Fig. 1. Weight loss of ‘Honey One’ (A) and ‘Earl`s Talent’ (B) muskmelon fruits during 21 days of ripening at 10°C and RT (25°C). Vertical bars indicate standard error of the mean (n = 5).. lower than that at RT due to temperature effects on evaporation of moisture from the product (Powrie and Skura, 1991). The respiration rate immediately after harvest was 25.73 mL·kg-1·h-1 in ‘Honey One’, which after 3 d decreased to 19.24 mL·kg-1·h-1 at RT and to 11.39 mL·kg-1·h-1 at 10°C and was maintained afterwards. In ‘Earl`s Talent’, the respiration rate was 24.88 mL·kg-1·h-1 after harvest and reduced to 20.93 mL·kg-1·h-1 at RT and 13.61 mL·kg-1·h-1 at 10°C after 3 d and was elevated to 26.64 mL·kg-1·h-1 at RT and 22.37 mL·kg-1·h-1 at 10°C on the 21st day (Fig. 2A and B). The cultivars showed significant (p < 0.05) differences from each other in respiration rate depending on temperature. In both cultivars, fruits ripened at 10°C showed a lower respiration rate than those at RT. In the study by Ning et al (1992), the respiration rate at RT was higher than that at low temperature, and Choi et al. (2001) reported that the enzyme involved in respiration was promoted by temperature change and respiration increased at high temperatures.. Changes in Ethylene, Acetaldehyde and Ethanol Production Rate During Ripening Period Changes in the gas production rate of muskmelon during ripening period are shown in Fig. 2. The concentration of C2H4 in ‘Honey One’ was 9.24 µL·kg-1·h-1 immediately after harvest and increased rapidly to 17.08 µL·kg-1·h-1 on day 3 at RT and then decreased afterwards. Ripening at 10°C led to low ethylene production in both cultivars. ‘Earl`s Talent’ showed a significant difference (p < 0.05) in ethylene production between ripening conditions only on days 3 and 15 of ripening. A low production rate of ethylene (7.55 µL·kg-1·h-1) was observed on ‘Earl`s Talent’ from the beginning and decreased continuously as the ripening period proceeded (Fig. 2C and D). Based on our results, we conclude that ripening of muskmelon at RT accelerates the production of ethylene and promotes softening and aging, especially in ‘Honey One’ (Fig. 2C).. The production of acetaldehyde and ethanol is related to the production of off flavors of fruits and vegetables during ripening. There was no significant (p > 0.05) difference in acetaldehyde production between the two ripening temperatures in both cultivars (Fig. 3C and D). In ‘Honey One’, the production rate of ethanol gradually increased as the ripening proceeded regardless of temperature; the ethanol production rate reached 6.94 µL·kg-1·h-1 at RT and 3.07 µL·kg-1·h-1 at 10°C on day 21. ‘Earl`s Talent’ showed a lower ethanol production rate compared to ‘Honey One’. On day 21 of ripening, the ethanol production rate was 6.48 µL·kg-1·h-1 and 2.97 µL·kg-1·h-1 at RT and 10°C respectively for ‘Earl’s Talent’ (Fig. 3C and D).. 746. Horticultural Science and Technology.

(7) Effect of Ripening Conditions on the Quality and Storability of Muskmelon (Cucumis melo L.) Fruits. In the present study, we observed that storage at 10°C maintained better quality than that at RT due to lower weight loss, respiration rate, and gas production rate. We concluded that ripening at the optimum temperature (10°C) not only inhibited the generation of odor during the ripening period but also maintained the quality of melon.. A. B. C. D. Fig. 2. Changes in respiration rate (A, B) and ethylene (C2H4) production rate (C, D) of ‘Honey One’ and ‘Earl`s Talent’ muskmelon fruits during 21 days of ripening at 10°C and RT (25°C). Vertical bars indicate standard error of the mean (n = 5).. A. B. C. D. Fig. 3. Changes in acetaldehyde (A, B) and ethanol (C, D) production rates of ‘Honey One’ and ‘Earl`s Talent’ muskmelon fruits during 21 days of ripening at 10°C and RT (25°C). Vertical bars indicate standard error of the mean (n = 5).. Horticultural Science and Technology. 747.

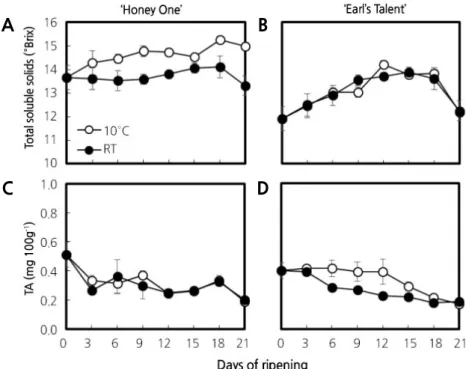

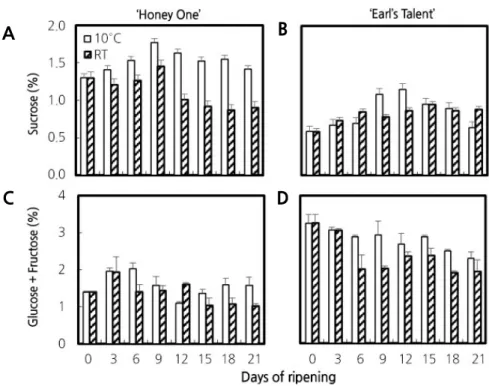

(8) Effect of Ripening Conditions on the Quality and Storability of Muskmelon (Cucumis melo L.) Fruits. Changes in Total Soluble Solids (TSS) and Titratable Acidity (TA) The changes in TSS of muskmelon fruits according to days of ripening is shown in Fig. 4A and B. A significant difference (p < 0.05) in TSS levels was observed between ripening conditions in ‘Honey One’ but ‘Earl`s Talent’ did not show a significant difference in TSS levels (p > 0.05) between ripening conditions during the ripening period. As the ripening period proceeded, TSS levels of both cultivars increased until day 18 then decreased. Immediately after harvest, the TSS of ‘Honey One’ was 13.6 °Brix and increased to 15.2 °Brix at 10°C and to 14.1 °Brix at RT on day 18. ‘Earl`s Talent’ showed similar trend as ‘Honey One’ as TSS levels increased from 11.9 to 14.2 °Brix at 10°C and to 13.8 °Brix at RT on 12th and 15th d, respectively. TSS of both cultivars after ripening at 10°C was higher than that of RT (Fig. 4A and B) and respiration rate at RT is higher than 10°C (Fig. 2A and B). TSS levels have been widely used as a measure of. melon quality (Cohen and Hicks, 1986). Changes in sugar content during storage of most fruits tend to coincide with the initial increase in TSS followed by TSS decrease during the ripening period (Yun et al., 2008). Yang et al. (2003) also reported a higher sugar content of melon stored at low temperature than at RT. TA, which is used as an indicator of acidity, was 0.51 mg/100 g for ‘Honey One’ and 0.40 mg/100 g for ‘Earl`s Talent’ immediately after harvest, and TA of both cultivars decreased regardless of the temperature during the ripening period (Fig. 4C and D). Similar results were reported by Youn et al. (2009). Koh et al. (1996) reported non-significant differences. in the sensory characteristics of citrus, but reported a decrease in TA content at lower temperatures.. A. B. C. D. Fig. 4. Changes in total soluble solids (TSS; A, B) and titratable acidity (TA; C, D) of ‘Honey One’ and ‘Earl`s Talent’ muskmelon fruits during 21 days of ripening at 10°C and RT (25°C). Vertical bars indicate standard error of the mean (n = 5).. Changes in Sugar Content The sugar content of melon consists mainly of the non-reducing sugars sucrose and the reducing sugars fructose and glucose. Significant differences (p < 0.05) were observed in sugar content between cultivars and ripening conditions. 748. Horticultural Science and Technology.

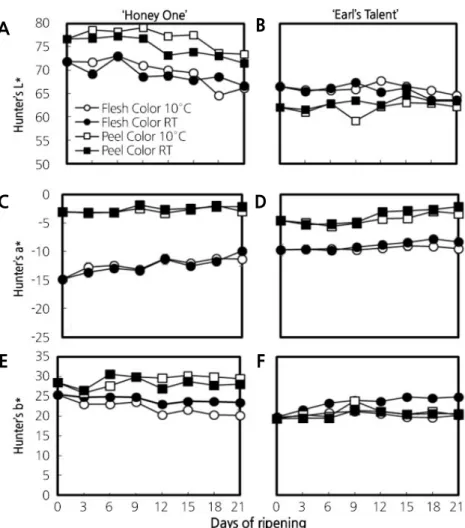

(9) Effect of Ripening Conditions on the Quality and Storability of Muskmelon (Cucumis melo L.) Fruits. during the ripening period. The quality of a melon is mainly determined by the amount of sucrose; increasing levels of sucrose were observed up to 9 and 12 d of ripening for ‘Honey One’ and ‘Earl`s Talent’, respectively, followed by decreasing levels as the ripening period proceeded at 10°C (Fig. 5A and B). In ‘Honey One’, the highest sucrose content (1.77%) was observed at 10°C on day 9 of ripening and decreased thereafter. The highest sucrose content (1.15%) in ‘Earl’s Talent’ was observed at 10°C after 12 d of ripening. ‘Earl`s Talent’ had lower sucrose but higher glucose and fructose levels than ‘Honey One’ (Fig. 5). This result indicates that more sucrose was converted to glucose and fructose in ‘Honey One’ as the fruits matured than in ‘Earl`s Talent’, and that fructose and glucose were then converted to energy by respiration (Lee et al., 1996). Hubbard et al. (1989) reported that melons accumulate sucrose as fruit development proceeds, with the highest sucrose concentration located in the innermost tissue.. A. B. C. D. Fig. 5. Changes in sucrose (A, B) and glucose + fructose (C, D) content of ‘Honey One’ and ‘Earl`s Talent’ muskmelon fruits during 21 days of ripening at 10°C and RT (25°C). Vertical bars indicate standard error of the mean (n = 5).. Changes in Color Variables During the ripening period, the color changes of both peel and flesh of muskmelon fruits was measured using a colorimetric method and expressed with L*, a* and b* color values (Fig. 6). Significant differences (p < 0.05) were observed between cultivars in color variables. In ‘Honey One’, the initial L* value immediately after harvest was 76.65 and 71.84 for peel and flesh, respectively, and gradually decreased until it reached 71.51 and 66.59, respectively, on day 21 at RT. At 10°C, Hunter`s L* values for ‘Honey One’ flesh and peel were higher than those at RT throughout the ripening period, but followed a similar trend. Ferrari et al. (2013) also reported that the L* value of melon decreased as storage period proceeded. Likewise, the L* value of ‘Earl`s Talent’ showed a similar decreasing trend regardless of the ripening temperature.. Horticultural Science and Technology. 749.

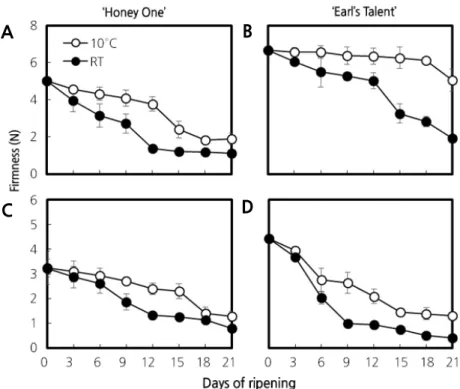

(10) Effect of Ripening Conditions on the Quality and Storability of Muskmelon (Cucumis melo L.) Fruits. In both cultivars the a* value showed non-significant (p > 0.05) differences in both flesh and peel color during the ripening period. Similar results were reported by Kim et al. (2011) (Fig. 6C and D). Changes in b* indicated non-significant (p > 0.05) differences in both flesh and peel color of ‘Honey One’ and ‘Earl`s Talent’ during the ripening period. However, the b* value of the flesh at RT was higher than that at 10°C for both cultivars throughout the ripening period (Fig. 6E and F). Unlike the present study, Kim et al. (2010) reported a trend of increasing b* value for up to 10 days of storage.. A. B. C. D. E. F. Fig. 6. Changes in color variables of ‘Honey One’ and ‘Earl`s Talent’ muskmelon fruits during 21 days of ripening at 10°C and RT (25°C). Vertical bars indicate standard error of the mean (n = 5).. Firmness Firmness is an important ripening and quality indicator and is considered as an index that consumers use to decide whether to purchase a melon (Nishiyama et al., 2007). In this study, we measured the firmness of flesh at 1 cm from the peel and 2 cm from the peel for both cultivars of muskmelon. Significant differences (p < 0.05) were observed between cultivars and ripening conditions. The firmness (1 cm from the peel) of ‘Honey One’ was 5.01 N immediately after harvest, decreased to 2.72 N on day 9 and continued decreasing until it reached 1.38 N on day 21 at RT. ‘Honey One’ firmness at 10°C was maintained at 3.78 N until day 12, then decreased to 1.90 N on the 21st day. ‘Earl`s Talent’ showed. 750. Horticultural Science and Technology.

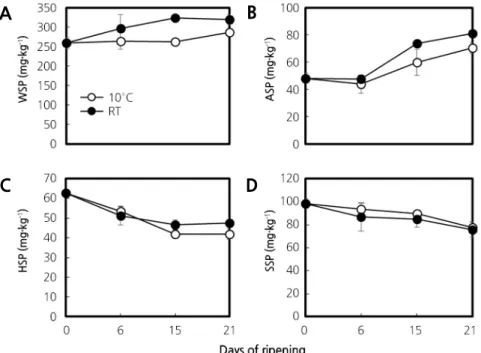

(11) Effect of Ripening Conditions on the Quality and Storability of Muskmelon (Cucumis melo L.) Fruits. a similar trend as ‘Honey One’ at both temperature conditions (Fig. 7A and B). These results showed that ‘Earl`s Talent’ maintained firmness longer than ‘Honey One’. The firmness (2 cm from the peel) decreased in both cultivars as ripening period proceeded (Fig. 7C and D). The firmness of both cultivars ripened at RT was lower than that of those ripened at 10°C. These results indicated that the stored contents are rapidly converted and the flesh tissue is softened and collapsed as the ripening period proceeded at RT (Fig. 7). It has been concluded that the rapid decrease in firmness is due to the rapid increase of PG activity and WSP when fruits are stored at high temperature (Kim, 1998; Lee et al., 2007; Kim et al., 2011).. A. B. C. D. Fig. 7. Changes in firmness 1 cm from the peel (A, B) and 2 cm from the peel(C, D) of ‘Honey One’ and ‘Earl`s Talent’ muskmelon fruits during 21 days of ripening at 10°C and RT (25°C). Vertical bars indicate standard error of the mean (n = 5).. PG Activity and Pectin Content PG activity of ‘Honey One’ reached 12.58 nmol·kg-1·s-1 on day 6 and decreased afterwards at RT (Fig. 8A). PG activity at 10°C was lower than RT up to day 9, which could be due to the effect of temperature on enzyme activity. In ‘Earl`s Talent’, the PG activity was higher than that of ‘Honey One’ at both temperature conditions (Fig. 8A and B). The firmness of ‘Earl`s Talent’ also decreased faster after days 12 and 6 at 1 cm and 2 cm from the peel, respectively, at RT; this effect could be due to the high PG activity at that stage (Figs. 7 and 8). Nogata et al. (1993) reported that PG activity decreased as maturity and ripening proceeded in strawberry fruit. Lamikanra et al (2003) also reported that PG activity decreased after 3 days of storage in fresh cut cantaloupe melon. Significant differences (p < 0.05) in pectin content were observed between cultivars and ripening conditions. The WSP and ASP contents of both cultivars increased with the progress of ripening but the HSP and SSP levels decreased as ripening proceeded (Figs. 9 and 10). The WSP content of the ‘Honey One’ melon was 259.16 mg·kg-1 immediately after. Horticultural Science and Technology. 751.

(12) Effect of Ripening Conditions on the Quality and Storability of Muskmelon (Cucumis melo L.) Fruits. harvesting but increased to 319.42 mg·kg-1 at RT and 287.32 mg·kg-1 at 10°C on day 21. The ASP content also increased from 48.17 mg·kg-1 immediately after harvesting to 81.22 mg·kg-1 at RT, and to 70.59 mg·kg-1 at 10°C on day 21. Similar trends were observed for WSP (Fig. 9). In ‘Earl`s Talent’, the initial WSP content was 274.16 mg·kg-1, but it was 280.47 mg·kg-1 at RT and 248.89 mg·kg-1 at 10°C on day 21. HSP and SSP also showed a decreasing trend as ripening proceeded regardless of ripening temperature and cultivar (Figs. 9 and 10). Similar to the present study, Shewfelt (1965) reported that the content of pectin was different between cultivars of peach, and WSP showed an increasing trend during ripening. Pressey et al. (1971) showed that total pectin content was different for different cultivars, and soluble pectin was consistent with an increasing trend during ripening.. A. B. Fig. 8. Changes in polygalacturonase activity of ‘Honey One’ (A) and ‘Earl`s Talent’ (B) muskmelon fruits during 21 days of ripening at 10°C and RT (25°C). Vertical bars indicate standard error of the mean (n = 3).. A. B. C. D. Fig. 9. Changes in WSP (water soluble pectin) (A), ASP (ammonium oxalate soluble pectin) (B), HSP (hydrochloric acid soluble pectin) (C) and SSP (sodium hydroxide soluble pectin) (D) of ‘Honey One’ muskmelon fruit during 21 days of ripening at 10°C and RT (25°C). Vertical bars indicate standard error of the mean (n = 3).. 752. Horticultural Science and Technology.

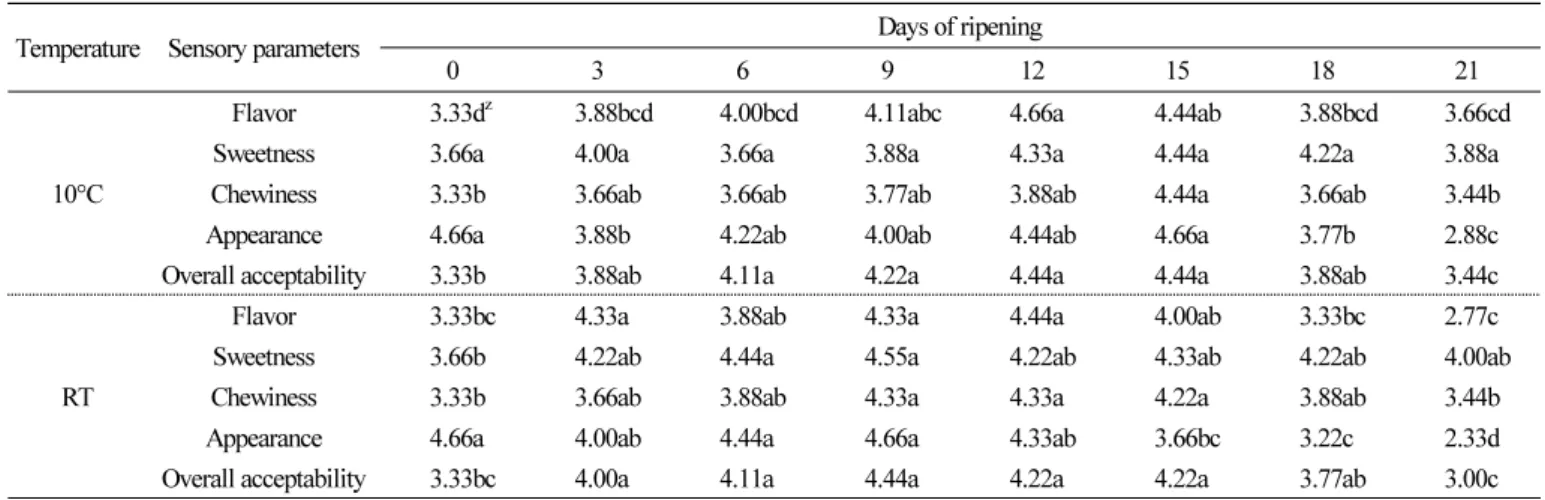

(13) Effect of Ripening Conditions on the Quality and Storability of Muskmelon (Cucumis melo L.) Fruits. A. B. C. D. Fig. 10. Changes in WSP (water soluble pectin) (A), ASP (ammonium oxalate soluble pectin) (B), HSP (hydrochloric acid soluble pectin) (C) and SSP (sodium hydroxide soluble pectin) (D) of ‘Earl`s Talent’ muskmelon fruit during 21 days of ripening at 10°C and RT (25°C). Vertical bars indicate standard error of the mean (n = 3).. Sensory Evaluation The Duncan’s multiple range test was used to evaluate the scores for sweetness, flavor, chewiness, appearance, and overall acceptability of melon (Tables 1 and 2). Sensory evaluation scores show that the evaluation points need to be above 3 for a melon to be marketable. The sweetness of both cultivars increased as the ripening period proceeded, with those stored at 10°C showing an increase in sweetness later than those at RT. ‘Earl`s Talent’ had less sugar than ‘Honey One’ and had a overall low preference score in sweetness. In the case of flavor, the longer the ripening period, the higher the occurrence of odor at RT due to off-flavor (acetaldehyde and ethanol) production. In the case of chewiness, both cultivars Table 1. Sensory characteristics of ‘Honey One’ muskmelon fruit during 21 days of ripening at 10°C and RT (25°C). Temperature Sensory parameters. 10°C. RT. Days of ripening 0. 3 z. 6. 9. 12. 15. 18. 21. Flavor. 3.33d. Sweetness. 3.66a. 3.88bcd 4.00a. 4.00bcd 3.66a. 4.11abc 3.88a. 4.66a 4.33a. 4.44ab 4.44a. 3.88bcd 4.22a. 3.66cd 3.88a. Chewiness Appearance Overall acceptability. 3.33b 4.66a 3.33b. 3.66ab 3.88b 3.88ab. 3.66ab 4.22ab 4.11a. 3.77ab 4.00ab 4.22a. 3.88ab 4.44ab 4.44a. 4.44a 4.66a 4.44a. 3.66ab 3.77b 3.88ab. 3.44b 2.88c 3.44c. Flavor Sweetness Chewiness. 3.33bc 3.66b 3.33b. 4.33a 4.22ab 3.66ab. 3.88ab 4.44a 3.88ab. 4.33a 4.55a 4.33a. 4.44a 4.22ab 4.33a. 4.00ab 4.33ab 4.22a. 3.33bc 4.22ab 3.88ab. 2.77c 4.00ab 3.44b. Appearance Overall acceptability. 4.66a 3.33bc. 4.00ab 4.00a. 4.44a 4.11a. 4.66a 4.44a. 4.33ab 4.22a. 3.66bc 4.22a. 3.22c 3.77ab. 2.33d 3.00c. z. Means with different letters in a row are significantly different at p < 0.05 by Duncan’s multiple range test (n = 10). Each value represents mean of the ratings evaluated using 5-point scale (1 = bad, 3 = fair, 5 = excellent acceptability).. Horticultural Science and Technology. 753.

(14) Effect of Ripening Conditions on the Quality and Storability of Muskmelon (Cucumis melo L.) Fruits. Table 2. Sensory characteristics of ‘Earl`s Talent’ muskmelon fruit during 21 days of ripening at 10°C and RT (25°C) Temperature Sensory parameters. 10°C. RT. Days of ripening 0. 3. 15. 18. 21. Flavor. 3.14az. 3.57a 3.57bc. 6. 3.71a 4.71a. 9. 3.28a 4.28bc. 12. 3.57a 4.42a. 3.28a 4.71a. 3.42a 2.28d. Sweetness. 2.00d. 3.28a 3.14c. Chewiness Appearance Overall acceptability. 2.00c 3.14a 3.14a. 3.14ab 3.71a 3.57a. 3.57ab 4.00a 3.42a. 3.85ab 3.14a 3.14a. 3.57ab 3.28a 3.14a. 4.00ab 3.71a 3.42a. 2.85b 3.14a 3.42a. 3.32b 3.00a 3.14a. Flavor Sweetness Chewiness. 3.14c 2.00b 2.00b. 3.42bc 2.85a 3.57a. 3.85abc 3.14a 3.71a. 4.71a 3.28a 4.00a. 4.28ab 3.28a 3.57a. 4.14ab 3.42a 3.71a. 4.14ab 3.42a 2.57b. 1.71d 3.08a 2.14b. Appearance Overall acceptability. 3.14bc 3.14bc. 3.71abc 3.57ab. 4.00ab 3.57ab. 4.14a 4.42a. 4.00ab 4.00ab. 3.85ab 4.14ab. 2.85cd 3.14bc. 2.14d 2.28c. z. Means with different letters in a row are significantly different at p < 0.05 by Duncan’s multiple range test (n = 10). Each value represents mean of the ratings evaluated using 5-point scale (1 = bad, 3 = fair, 5 = excellent acceptability).. showed low scores at the early stage of ripening due to higher firmness; higher scores were obtained as the ripening proceeded, indicating that the flesh of melons was softened. In appearance, both cultivars showed lower scores as the ripening proceeded, which is probably due to loss of the moisture of the stalk and to the dryness of the peel. In overall acceptability, both cultivars achieved the best scores on the 15th day at 10°C and on 9th day at RT.. Conclusions The study was conducted to characterize the effect of ripening conditions on quality of ‘Honey One’ and ‘Earl`s Talent’ melon fruits stored at 10°C with 80 ± 5% RH and RT (25°C with 50 ± 5% RH). Overall, the results of this study revealed that the melon quality was highest on the 15th day of ripening at 10°C and on the 9th day of ripening at RT irrespective of cultivar.. Literature Cited Blumenkrantz N, Asboe-Hansen G (1973) New method for quantitative determination of uronic acids. Biochem Anal Biochem 54:484-489. doi:10.1016/0003-2697(73)90377-1 Choi HK, Park SM, Yoo KC, Jeong CS (2001) Effects of shelf temperature on the fruit quality of muskmelon after storage. Korean J Hortic Sci Technol 19:135-139 Ferrari CC, Sarantopoulos CI, Carmello-Guerreiro SM, Hubinger MD (2013) Effect of osmotic dehydration and pectin edible coatings on quality and shelf life of fresh-cut melon. Food Bioproc Technol 6:80-91. doi:10.1007/s11947-011-0704-6 Gross KC (1982) A rapid and sensitive spectrophotometric method for assaying polygalacturonase using 2-cyanoacetamide. HortScience 17:933-934 Hubbard NL, Huber SC, Pharr DM (1989) Sucrose phosphate synthase and acid invertase as determinants of sucrose concentration in developing muskmelon (Cucumis melo L.) fruits. Plant Physiol 91:1527-1534. doi:10.1104/pp.91.4.1527 Hwang J (1991) Contribution of side branches of apple and tomato pectins to their rheological properties. PhD Diss., Rutgers University, New Brunswick, NJ, USA Kim JY, Kwon HK, Gu KH, Kim BS (2011) Selection of quality indicator to determine the freshness of muskmelon (Cucumis melo L.) during distribution. Korean J Food Preserv 18:824-829. doi:10.11002/kjfp.2011.18.6.824 Kim M (1998) A study on the post-harvest physiology of Citrus unshiu Marc. Var. okitsu, during transportation. Korean J Postharvest Sci. 754. Horticultural Science and Technology.

(15) Effect of Ripening Conditions on the Quality and Storability of Muskmelon (Cucumis melo L.) Fruits. Technol 5:339-341 Kim MS, Min JH, Chun JP, Kim JG, Lee EM, Lee JY, Hwang YS (2010) Effect of 1-MCP and high -CO2 treatment on the firmness and pectin changes in peach (Prunus persica) fruit during shelf-life. J Agric Sci 37:209-216 Kim YH, Hwang BH, Kim JK (2007) Changes in soluble and transported sugars content and activity of their hydrolytic enzymes in muskmelon (Cucumis melo L.) fruit during development and senecence. Korean J Hortic Sci Technol 25:89-96. doi:10.1016/ j.scienta.2006.11.015 Kintner PK, Van Buren JP (1982) Carbohydrate interference and its correction in pectin analysis using the m‐hydroxydiphenyl method. J Food Sci 47:756-759. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2621.1982.tb12708.x Koh JS, Yang SH, Kim SH (1996) Cold storage of Citus unshiu Marc. var. okitsu produced in Cheju. Korean J Postharvest Sci Technol 3:105-111 Lamikanra O, Juaraez B, Watson MA, Richard OA (2003) Effect of cutting and storage on sensory traits of cantaloupe melon cultivars with extended postharvest shelf life. J Sci Food Agric 83:702-708. doi:10.1002/jsfa.1337 Lee JS, Chung DS, Lee JU, Lim BS, Lee YS, Chun CH (2007) Effects of cultivars and storage temperatures on shelf-life of leaf lettuces. Korean J Food Preserv 14:345-350 Lee TI, Jeong CS, Chang YK (1996) Patterns of sugar accumulation of muskmelon cultivars in relation 10 spring and fall cultivation. J Kor Soc Hortic Sci 37:746-750 Lester G, Shellie KC (1992) Postharvest sensory and physicochemical attributes of honey dew melon fruits. HortScience 27:1012-1014 Manabe M, Naohara J (1986) Properties of pectin in Satsuma mandarin fruits (Citrus unshiu Marc.). Jpn J Food Ind 33:602-608 McCready RM, McComb EA (1952) Extraction and detennination of total pectic materials fruits. Anal Chem 24:1986-1988. doi:10.1021/ac60072a033 Ning B, Kubo Y, Inaba A, Nakamura R (1992) Effects of storage temperature on the occurrence of chilling injury and storage life in Chinese pear ‘Yali’. J Jpn Soc Hortic Sci 61:461-467. doi:10.2503/jjshs.61.461 Nishiyama K, Guis M, Rose JK, Kubo Y, Bennett KA, Wangjin L, Kato K, Ushijima K, Nakano R, et al (2007) Ethylene regulation of fruit softening and cell wall disassembly in α1arentais melon. J Exp Bot 58:1281-1290. doi:10.1093/jxb/erl283 Nogata Y, Ohta H, Voragen AGJ (1993) Polygalacturonase in strawberry fruit. Phytochemistry 34:617-620. doi:10.1016/00319422(93)85327-N Oh SH, Bae R, Lee SK (2011) Current status of the research on the postharvest technology of melon (Cucumis melo L.). Korean J Food Preserv 18:442-458. doi:10.11002/kjfp.2011.18.4.442 Park DS, Shimeles T, Hyun JY, Kwon HS, Jeong CS (2016) Effect of ripening conditions on quality of winter squash ‘Bochang’. Korean J Food Sci Technol 48:142-146. doi:10.9721/KJFST.2016.48.2.142 Park KW, Kang HM, Kim CH (2000) Comparison of storability on film sources and storage temperature for fresh Japanese mint in MA storage. J Bio-Environ Control 9:40-46 Park YJ, Moon KD (2004) Influence of preheating on quality changes of fresh-cut muskmelon. Korean J Food Preserv 11:170-174 Powrie WD, Skura BJ (1991) Modified atmoshere packaging of fruits and vegetables. In Modified Atmosphere Packaging of Food. Springer, USA, pp 169-245. doi:10.1007/978-1-4615-2117-4_7 Pressey R, Hinton DM, Avants JK (1971) Development of polygalacturonase activity and solubilization of pectin in peaches during ripening. J Food Sci 36:1070-1073. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2621.1971.tb03348.x Robertson GL, Swinburne D (1981) Changes in chlorophyll and pectin after storage and canning of kiwifruit. J Food Sci 46:1557-1559. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2621.1981.tb04219.x Roe B, Bruemmer JH (1981) Changes in pectic substances and enzymes during ripening and storage of “Keitt” mangos. J Food Sci 46:186-189. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2621.1981.tb14560.x Rouse AH, Atkins CD, Moore EL (1962) Seasonal changes occurring in the pectinesterase activity and pectic constituents of the component parts of citrus fruits. I. Valencia oranges. J Food Sci 27:419-425. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2621.1962.tb00120.x Sangwanangkul P, Bae YS, Lee JS, Choi HJ, Choi JW, Park MH (2017) Short-term pretreatment with high CO2 alters organic acids and improves cherry tomato quality during storage. Hortic Environ Biotechnol 58:127-135. doi:10.1007/s13580-017-0198-x Shewfelt AL (1965) Changes and variations in the pectic constitution of ripening peaches as related to product firmness. J Food Sci 30:573. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2621.1965.tb01804.x Tilahun S, Seo MH., Park DS, Jeong, CS (2018) Effect of cultivar and growing medium on the fruit quality attributes and antioxidant properties of tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.). Hortic Environ Biotechnol 59:215-223. doi:10.1007/s13580-018-0026-y Yang B, Shiping T, Hongxia L, Jie Z, Jiankang C, Yongcai L, Weiyi Z (2003) Effect of temperature on chilling injury, decay and quality of Hami melon during storage. Postharvest Biol Technol 29:229-232. doi:10.1016/S0925-5214(03)00104-2 Youn AR, Kwon KH, Kim BS, Kim SH, Noh BS, Cha HS (2009) Changes in quality of muskmelon (Cucumis melo L.) during storage at different temperatures. Korean J Food Sci Technol 41:251-257 Yun HJ, Lim SY, Hur JM, Lee BY, Choi YJ, Kwon JH, Kim DH (2008) Changes of nutrituinal compounds and texture characteristics of peaches (Prunus persica L. Batsch) during post-irradiation storage at different temperature. Korean J Food Preserv 15:377-384 Zhang X, Lee FZ, Eun JB (2007) Changes of phenolic compounds and pectin in Asian pear fruit during growth. Korea J Food Sci Technol 39:7-13. Horticultural Science and Technology. 755.

(16)

수치

관련 문서

Changes in body, flexibility, and physical strength levels of women participating in Pilates have a significant influence on psychological chan ges.. Summarizing

Second, analyzing students' level of interest in the unit of Clothes and Life Style revealed that there was significant difference between genders and students in the two

Interest in sustainability and improving the quality of living has brought changes in the measurement and judgement for the quality of living.

2) In between-group comparison before and after elastic band exercise, a significant difference was found in the percentage of body fat, fat-free

Fourth, for the sub-factors of personality traits according to weight lifters’ education, while there was a high difference in neuroticism and agreeableness

As for the number of participation, significant difference was found in accessibility, attractiveness and comfort of physical environment, recognition and

Conclusions : No significant corelation of the patency rate was shown in the study on the effects of local irrigation and systemic application of heparin

The change in active oxygen was decreased after exercise in the exercise group than in the control group, and there was a statistically significant