171

CASE REPORTDOI 10.4070 / kcj.2009.39.4.171

Print ISSN 1738-5520 / On-line ISSN 1738-5555 Copyright ⓒ 2009 The Korean Society of Cardiology

Intravascular Ultrasound-Guided Troubleshooting in a Large Hematoma Treated With Fenestration Using a Cutting Balloon

Hye Jin Noh, MD, Jin-Ho Choi, MD, Young Bin Song, MD, Hyun Chul Jo, MD, Ji Hyun Yang, MD, Sang Min Kim, MD, Hyun Jong Lee, MD, Joon Hyuk Choi, MD,

Soo Hee Choi, MD, Joo Yong Hahn, MD, Seung Hyuk Choi, MD and Hyeon Cheol Gwon, MD

Division of Cardiology, Department of Internal Medicine, Cardiac and Vascular Center, Samsung Medical Center, Sungkyunkwan University School of Medicine, Seoul, KoreaABSTRACT

Intramural hematoma formation is not a well-studied complication of percutaneous coronary intervention. We describe a patient with stable angina who developed an intramural hematoma during elective percutaneous coro- nary intervention (PCI) in the right coronary artery (RCA). Total occlusion with dense dye staining developed a long way from the distal RCA, near the posterior descending artery bifurcation site. The true lumen was compre- ssed by the enlarged, tense, false lumen. The patient was successfully treating with intravascular ultrasound-guided fenestration using a cutting balloon, and a stent was implanted in the distal RCA.

(Korean Circ J 2009;39:171-174) KEY WORDS:Hematoma; Angioplasty; Intravascular ultrasonography.

Introduction

The rate of periprocedural coronary occlusion has been reported to be 6.7% in the setting of balloon angio- plasty.

1)Acute closure of a coronary artery associated with dissection, coronary spasm, and/or thrombus formation usually occurs within 6 hours after balloon angioplasty.

2)Several case reports have shown a different type of dissec- tion morphology suggestive of intramural hematoma for- mation.

3-6)Post-percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) intramural hematomas have not been well studied, and their prevalence is unknown. Intramural hematomas are difficult to diagnose angiographically, and they may be missed when they do not cause severe luminal narrowing.

Treatment may be conservative or may entail stenting or surgery.

We present an interesting case of an intramural he- matoma complicating elective PCI. The patient was suc- cessfully treated with cutting balloon fenestration and stent implantation.

Case

A 72-year-old woman was admitted to our hospital to be evaluated for a 5-year history of exertional chest pain.

She had suffered from diabetes and hypertension for 25 years. On admission, her blood pressure was 126/75 mmHg, and her pulse rate was 92 bpm. There were no specific findings on electrocardiography or echocardio- graphy. Cardiac serum markers were within normal range, and the N-terminal proB-type natriuretic peptide level was 706.9 pg/mL. Coronary angiography revealed focal stenosis leading to 90% luminal narrowing of the mid- right coronary artery (RCA), 99% narrowing of the pos- terior descending artery (PDA) ostium, and 95% narrow- ing of the distal left circumflex artery (LCX) (Fig. 1).

One-stage elective PCI was performed for mid-RCA, PDA ostial, and distal LCX lesions. We started PCI with a Runthrough guidewire (Terumo, Japan) and a 6 Fr Jud- kins right guiding catheter (Cordis, Florida, USA). The simple 90% mid-RCA focal lesion was dilated with a 3.0×15 mm balloon (12 atm) and treated with a 3.5×

24 mm zotarolimus-eluting stent (Endeavor, Medtronic, Minnesota, USA) (12 atm). Unexpected total occlusion and dye staining developed near the PDA bifurcation site after ballooning was complete (Fig. 2). The patient experienced significant chest pain, and her blood pres- sure decreased to 85/50 mmHg. We attempted catheter thrombectomy with a Thrombuster aspiration catheter (Kaneka, Japan) and attempted another dilatation using

Received: November 14, 2008 Revision Received: November 17, 2008 Accepted: November 19, 2008

Correspondence: Jin-Ho Choi, MD,Division of Cardiology, Department of Internal Medicine, Cardiac and Vascular Center, Samsung Medical Center, Sungkyunkwan University School of Medicine, 50 Irwon-dong, Gangnam- gu, Seoul 135-710, Korea

Tel: 82-2-3410-6547, Fax: 82-2-3410-3849 E-mail: choijinh@skku.edu

172

·Hematoma Treated With IVUS-Guided Fenestration During PCIa 3.0×15 mm balloon, but we were unsuccessful. Intra- vascular ultrasound (IVUS) study revealed a totally com- pressed lumen stretching from the stented segment to the far distal RCA, which was caused by a huge hematoma (Fig. 3). We planned for fenestration between the true lumen and the hematoma. A 2.75×10 mm cutting bal- loon was placed at the RCA-PDA bifurcation site and dilated gently up to 4 atm, after which it burst (Fig. 4).

A 2.5×10 mm cutting balloon was dilated in the pos-

terolateral branch (4 atm) and PDA ostium (1.5 atm), in succession. Angiography showed restored thrombolysis in myocardial infarction (TIMI)-3 flow with a huge, long dissection spanning from the middle of the stented seg- ment to the far distal RCA. This dissection was further confirmed by an additional IVUS study. In the interest of minimizing the dissected segment, a 3.0×30 mm Endeavor stent (12 atm) was implanted in the distal RCA. The final angiography was acceptable. After the procedure, the patient’s symptoms subsided, and her

Fig. 1. Elective coronary angiography. The arrow indicates focal stenosis leading to 90% luminal narrowing in the mid-right coro- nary artery. The arrowhead indicates 99% luminal narrowing of the posterior descending artery ostium.

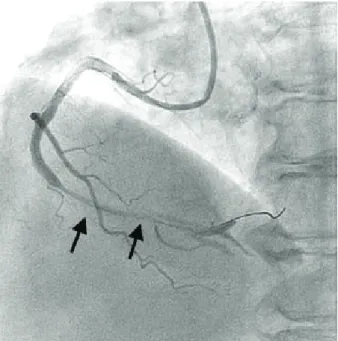

Fig. 2. Angiographic view of new narrowing that formed after stenting. Arrows indicate total occlusion and dye staining far from the distal right coronary artery, near the posterior descending artery bifurcation site.

Fig. 3. Site of the intramural hematoma that formed after stent- ing. Intravascular ultrasound revealed total compression of the distal right coronary artery lumen, which was caused by a huge hematoma (arrowheads).

Fig. 4. Coronary angiogram after cutting balloon fenestration be- tween the true lumen and the hematoma.

Hye Jin Noh, et al.·

173

blood pressure returned to normal range. She was dis- charged after 4 days and followed in the outpatient de- partment for more than 6 months, with no symptoms.

Discussion

Intramural hematoma formation is a rare but poten- tially life-threatening complication occurring after angio- plasty.

7)It is defined as an accumulation of blood within the medial space. It is a variant of dissection characterized by no direct communication between the true and false lumens.

8)In a study of 905 patients undergoing PCI, in- tramural hematomas were detected in 6.7% using IVUS.

1)The hematoma was proximal to the lesion in 36 percent, confined to the lesion in 18 percent, and distal to the lesion in 46 percent.

1)Patients with intramural hemato- mas had a greater than 3-fold increase in their target ves- sel revascularization rate within 1 month.

1)Intramural hematoma formation occurs through sub- intimal dissection into the media, with extension into the medial space of the contiguous normal arterial seg- ments where blood accumulates without a flap or iden- tifiable entry or exit points. Murphy et al.

3)studied patie- nts who underwent emergent coronary artery bypass surgery (CABG) after PCI and found that all had false lumens with bloody fluid, suggesting dissecting hemato- mas. Block et al.

5)reported a patient who died 90 hours after balloon angioplasty and who had a dissecting he- matoma originating at the angioplasty site and extend- ing distally. One common location for dissection after angioplasty is at the junction of the thinnest plaque and adjacent normal arterial wall.

9)10)During PCI, the stiffer atherosclerotic plaque resists circumferential expansion more than the normal site does, and high shear stresses are generated at their interface, promoting dissection.

11)Waller et al.

12)reported that the thickness of the media behind the atherosclerotic plaque is less than half that of the normal wall. Similarly, after stent implantation, dissection may occur at the edge of a stent; that is, the transition point between the rigid stent and the unstent- ed segment.

13)Angiographic findings of a intramural hematoma in- clude tapering encroachment of the lumen, absence of a dissection flap, and refractoriness to intracoronary vaso- dilators.

6)14)One third of all intramural hematomas show no angiographic abnormalities. In these cases, IVUS is the only diagnostic tool that can identify post-PCI intra- mural hematoma formation.

1)Because IVUS permits detailed high-quality cross-sectional imaging of the cor- onary arteries, it allows for detection of intramural he- matomas with or without luminal compression.

2)IVUS can identify the entry site and expansion of the hemato- ma into normal segments of the arterial wall. On IVUS, an intramural hematoma appears as a homogeneous, hyperechoic, crescent-shaped area.

15-17)Echogenicity de-

pends on the flow rate, red cell aggregation, and fibrin content. Intramural hematomas can also contain disti- nct echolucent zones within the hyperechoic areas.

18)These echolucent areas represent accumulation of radio- graphic contrast or saline within the hematoma space.

1)Proper management of post-PCI intramural hemato- mas has not been well-defined. However, short-term complications (non-Q-wave myocardial infarction and need for repeat revascularization within 1 month) and long-term outcomes (death and need for repeat revascu- larization at 1 year) are serious.

1)Bailout therapies to relieve the luminal obstruction include stenting or redi- latation and creation of a typical dissection.

15)Massive hematomas may require stent implantation to optimize blood flow. If the hematoma is extensive, long lesion stent deployment may be neccessary.

19)The use of angio- plasty alone, without stenting, is associated with a po- tential risk of dissection propagation.

20)IVUS may be useful in determining and controlling the bailout therapy, which includes stenting of the entry point at the initial dilatation site. Surgery must be considered in patients who have hematomas extending into the left main coro- nary artery.

15)We reported a case of acute vessel obstruction after coronary stenting, due to intramural hematoma forma- tion. IVUS offers advantages in determining the under- lying mechanism of luminal narrowing.

Acknowledgments

We thank Ms. Gyeong-Ja Jeong and Miss Youn-Jin Noh for their assistance in writing this manuscript.

REFERENCES

1) Maehara A, Mintz GS, Bui AB, et al. Incidence, morphology, an- giographic findings, and outcomes of intramural hematomas after percutaneous coronary interventions. Circulation 2002;105:2037- 42.

2) Hirose M, Kobayashi Y, Kreps EM, et al. Luminal narrowing due to intramural hematoma shift from left anterior descending coronary artery to left circumflex artery. Catheter Cardiovasc In- terv 2004;62:461-5.

3) Murphy DA, Craver JM, King SB 3rd. Distal coronary artery dissection following percutaneous transluminal coronary angio- plasty. Ann Thorac Surg 1984;37:473-8.

4) Zack PM, Ischinger T. Late progression of an asymptomatic in- timal tear to occlusive coronary artery dissection following an- gioplasty. Cathet Cardiovasc Diagn 1985;11:41-8.

5) Block PC, Myer RK, Stertzer S, Fallon JT. Morphology after tr- ansluminal angioplasty in human beings. N Engl J Med 1981;

305:382-5.

6) Stauffer JC, Sigwart U, Goy JJ, Kappenberger L. Milking dissec- tion: an unusual complication of emergency coronary artery stent- ing for acute occlusion. Am Heart J 1991;121:1539-42.

7) Shirodaria C, van Gaal WJ, Banning AP. A bleeding kiss: intra- mural haematoma secondary to balloon angioplasty. Cardiovasc Ultrasound 2007;5:21.

8) Song JK, Kang DH, Lee KM, et al. Two cases of aortic intramural hematoma diagnosed with transesophageal echocardiography.

Korean Circ J 1994;24:904-9.

174

·Hematoma Treated With IVUS-Guided Fenestration During PCI9) van der Lugt A, Gussenhoven EJ, von Birgelen C, Tai JA, Pieter- man H. Failure of intravascular ultrasound to predict dissection after balloon angioplasty by using plaque characteristics. Am Heart J 1997;134:1075-81.

10) Farb A, Virmani R, Atkinson JB, Kolodgie FD. Plaque morpho- logy and pathologic changes in arteries from patients dying after coronary balloon angioplasty. J Am Coll Cardiol 1990;16:1421-9.

11) Lee RT, Kamm RD. Vascular mechanics for the cardiologist. J Am Coll Cardiol 1994;23:1289-95.

12) Waller BF. The eccentric coronary atherosclerotic plaque: mor- phologic observations and clinical relevance. Clin Cardiol 1989;

12:14-20.

13) Sheris SJ, Canos MR, Weissman NJ. Natural history of intrava- scular ultrasound-detected edge dissections from coronary stent deployment. Am Heart J 2000;139:59-63.

14) Werner GS, Figulla HR, Grosse W, Kreuzer H. Extensive intra- mural hematoma as the cause of failed coronary angioplasty:

diagnosis by intravascular ultrasound and treatment by stent im- plantation. Cathet Cardiovasc Diagn 1995;36:173-8.

15) Werner GS, Diedrich J, Kreuzer H. Sonographic and angiographic features of intramural hematoma as a cause of failed coronary angioplasty. J Invasive Cardiol 1996;8:208-14.

16) Mintz GS, Nissen SE, Anderson WD, et al. American College of Cardiology Clinical Expert Consensus Document on Standards for the Acquisition, Measurement, and Reporting of Intravascular Ul- trasound Studies: a report of the American College of Cardiology Task Force on Clinical Expert Consensus Documents. J Am Coll Cardiol 2001;37:1478-92.

17) Mahr P, Ge J, Haude M, Gorge G, Erbel R. Extramural vessel wall hematoma causing a reduced vessel diameter after coronary ste- nting: diagnosis by intravascular ultrasound and treatment by stent implantation. Cathet Cardiovasc Diagn 1998;43:438-43.

18) Fowlkes JB, Strieter RM, Downing LJ, et al. Ultrasound echoge- nicity in experimental venous thrombosis. Ultrasound Med Biol 1998;24:1175-82.

19) Sawada T, Shite J, Shinke T, et al. Persistent malapposition after implantation of sirolimus-eluting stent into intramural coronary hematoma: optical coherence tomography observations. Circ J 2006;70:1515-9.

20) Ahn SG, Tahk SJ, Choi JH, et al. Spontaneous coronary artery dissection manifested during ergonovine test and treated with intravascular ultrasound guided stenting: a case report. Korean Circ J 2005;35:264-8.