Awake fiberoptic nasotracheal intubation for patients with difficult airway

Masanori Tsukamoto

1, Takashi Hitosugi

2, Takeshi Yokoyama

21Department of Dental Anesthesiology, Kyushu University Hospital, Fukuoka, Japan

2Department of Dental Anesthesiology, Faculty of Dental Science, Kyushu University, Fukuoka, Japan

Awake fiberoptic nasotracheal intubation is a useful technique, especially in patients with airway obstruction.

It must not only provide sufficient anesthesia, but also maintain spontaneous breathing. We introduce a method to achieve this using a small dose of fentanyl and midazolam in combination with topical anesthesia. The cases of 2 patients (1 male, 1 female) who underwent oral maxillofacial surgery are reported. They received 50 µg of fentanyl 2-3 times (total 2.2-2.3 µg/kg) at intervals of approximately 2 min. Oxygen was administered via a mask at 6 L/min, and 0.5 mg of midazolam was administered 1-4 times (total 0.02-0.05 mg/kg) at intervals of approximately 2 min. A tracheal tube was inserted through the nasal cavity after topical anesthesia was applied to the epiglottis, vocal cords, and into the trachea through the fiberscope channel. All patients were successfully intubated. This is a useful and safe method for awake fiberoptic nasotracheal intubation.

Keywords: Conscious Sedation; Fiberoptic Nasotracheal Intubation; Topical Anesthesia.

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/) which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Received: July 7, 2018•Revised: August 12, 2018•Accepted: September 11, 2018

Corresponding Author:Masanori Tsukamoto, Department of Dental Anesthesiology, Kyushu University Hospital, 3-1-1 Maidashi, Higashi-ku, Fukuoka 812-8582, Japan Tel: +81-92-642-6480 Fax: +81-92-642-6481 E-mail: tsukamoto@dent.kyushu-u.ac.jp

Copyrightⓒ 2018 Journal of Dental Anesthesia and Pain Medicine

INTRODUCTION

Nasotracheal intubation is often preferable to oral intubation in maxillofacial surgery [1]. It provides unrestricted access to the mouth, which facilitates the insertion of instruments. Fiberoptic intubation is a very useful technique for patients with an anticipated difficult airway, such as those with reduced mouth opening due to infection, temporomandibular joint problems, or jaw fracture [2,3].

With difficult airways, the anatomy is often deviated from normal, and comorbid conditions may lead to complete loss of the airways. Thus, close attention must be devoted to the anesthetic drugs and dosages used to achieve sedation and analgesia for nasal intubation [1].

The ideal sedation technique enables patients to maintain spontaneous ventilation, to be cooperative, and to tolerate passage of a fiberscope to facilitate nasotracheal intu- bation. It is important for patients undergoing sedated―

but awake―fiberoptic intubation to have decreased anxiety, discomfort, and hemodynamic disturbances.

During awake intubation, laryngospasm and coughing in response to intubation can be troublesome. Thus, effective topical airway anesthesia is mandatory for the comfort of the awake patient and subsequent successful airway instrumentation. Profound topical anesthesia of the airway also reduces the need for higher doses of sedatives and analgesics such as midazolam and fentanyl [4-6].

However, the optimal dose of topical anesthetic drug required before fiberoptic-assisted nasotracheal intubation under sedation remains unclear. We report 2 cases of

Masanori Tsukamoto, et al

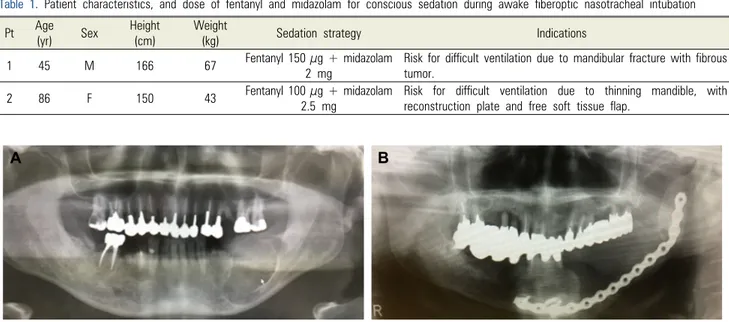

Fig 1. Reasons for conscious sedation. (A) Left lower fibrous tumor, (B) Postoperative infection after the patient underwent mandibular resection and reconstruction with a metal instrument for left mandibular gingiva.

Table 1. Patient characteristics, and dose of fentanyl and midazolam for conscious sedation during awake fiberoptic nasotracheal intubation Pt Age

(yr) Sex Height (cm)

Weight

(kg) Sedation strategy Indications

1 45 M 166 67 Fentanyl 150 μg + midazolam

2 mg Risk for difficult ventilation due to mandibular fracture with fibrous tumor.

2 86 F 150 43 Fentanyl 100 μg + midazolam

2.5 mg

Risk for difficult ventilation due to thinning mandible, with reconstruction plate and free soft tissue flap.

awake fiberoptic nasotracheal intubation under sedation using a low dose of midazolam and fentanyl in combi- nation with topical lidocaine airway anesthesia.

CASES

The cases of two patients (1 male, 1 female) who underwent oral maxillofacial surgery under general anesthesia are described. The clinical characteristics of these patients are summarized in Table. 1. Because of physical findings of increased risk for airway compro- mise, the anesthetic strategy included fiberoptic naso- tracheal intubation under sedation and topical anesthesia of the airway (Fig. 1). No premedication was admini- stered to the patients on the day of surgery. After placement of a nasal catheter, oxygen at 6 L/min was initiated. Noninvasive monitoring, including blood pressure and bispectral index (BIS) measurement, electrocardiography, and pulse oximetry, were initiated.

After peripheral venous access was obtained, the patients received intravenous fentanyl and midazolam. First, 50 µg of fentanyl was administered two or three times (total 2.2-2.3 µg/kg) at intervals of approximately 2 min. On

commencement of 6 L/min of oxygen via mask, 0.5 mg of midazolam was administered one to four times (total 0.02-0.05 mg/kg) at 2-min intervals based on hemo- dynamics, BIS, and Observer Assessment of Alertness/

Sedation Scale (OAA/S) score.

After adequate sedation was achieved with anxiolysis/

sedation, as defined by OAA/S level 3 or 4, a wooden applicator stick with a cotton swab, impregnated with 2 mL of 2% lidocaine containing 1:200,000 epinephrine, was inserted through the nasal meatus to verify the nasal passage to the pharyngeal space. A nasopharyngeal airway of either 8.0 mm or 9.5 mm (outside diameter) was inserted to confirm the patency of the nasal passage.

After removal of the nasal airway, a nasotracheal tube was then advanced into the pharynx. A fiberoptic scope (Pentax FB-15, HOYA, Tokyo, Japan) was advanced through the nasotracheal tube and 2 mL of 1% lidocaine (20 mg) with 3 mL of air in a 5 mL syringe was first sprayed onto the epiglottis via the working channel of the fiberscope. The fiberscope was then advanced toward the glottis. The patient was instructed to take a deep breath, which lifted the epiglottis anteriorly. The fiber- scope was then passed behind the epiglottis to visualize the vocal cords. A second dose of 2 ml of 1% lidocaine

A B

(20 mg) was sprayed via the previously described method toward the vocal cords, and the scope was then advanced through the glottis opening into the trachea during spontaneous inspiration. The tip of the fiberscope was then positioned immediately proximal to the carina. A third dose of 1% lidocaine (20 mg [2 mL]) was sprayed into the trachea using the previous method into the trachea. If visualization or orientation was lost at any time, the fiberscope was withdrawn until an appropriate landmark was identified. Finally, with profound topical anesthesia of the entire airway, the nasotracheal tube was then smoothly advanced into its correct final position as confirmed by the presence of positive end-tidal carbon dioxide and auscultation of bilateral breath sounds.

Rocuronium (0.6 mg/kg) and propofol (1-1.5 mg/kg) were then intravenously administered for induction of general anesthesia.

Anesthesia was maintained using inhalational anes- thetic agents, air and oxygen, in addition to an intra- venous infusion of remifentanil. The surgeries proceeded uneventfully and both patients were fully awake after anesthesia for extubation with no complications.

DISCUSSION

Management of the difficult airway is a challenge to anesthesiologists, and may lead to life-threatening complications. It has been reported that 1-18% of patients have a difficult airway [5]. We presented two cases of awake fiberoptic nasotracheal intubation, in which topical anesthetic (lidocaine 60 mg) was sprayed into the airway, combined with a low dose of midazolam (0.02-0.05 mg/kg) and fentanyl (2.2-2.3 µg/kg).

In these patients, we anticipated difficult ventilation or intubation because of possible airway obstruction. It was essential that the sedatives and opioids be administrated slowly and carefully, and titrated in low dosages to prevent any airway complications and to suppress stimu- lation of the airway with sufficient topical anesthetic.

We previously reported an in vitro study describing the

most effective method for spreading the anesthetic spray via the working channel of a fiberscope to mimic the spraying of topical anesthesia in the airway [7]. Spraying involving a fiberoptic scope and a 5 ml syringe containing 2 ml of liquid and 3 ml of air was determined to be most effective method for topical anesthesia of the epiglottis, vocal cord, and trachea. As a topical anesthetic, lidocaine is most frequently used because it has a good safety and efficacy profile, and major adverse effects manifest only if the total dose of injected lidocaine exceeds 5-7 mg/kg [4,6]. In clinical practice, we have successfully performed sufficient airway anesthesia with a total dose of lidocaine of 60 mg. Therefore, we could perform awake naso- tracheal intubation using lower doses of midazolam and fentanyl compared with previous reports [2,7,8].

Midazolam is a classic sedative, and is a short-acting benzodiazepine derivative. It has anxiolytic and sedative properties [6-8]. While midazolam is believed to cause minimal hemodynamic effects, it does have the potential to cause loss of airway reflexes. Thus, careful titration to the desired sedative level is necessary for achieving safe conscious sedation.

Awake intubation could be associated with painful stimulation during passage of the tracheal tube through the nose and the larynx. Opioids are potent analgesics and can help attenuate coughing and hemodynamic changes. Fentanyl is a short-acting opioid that quickly provides analgesia, mild sedation and analgesia with hemodynamic stability, all of which are beneficial for awake intubation; however, there is a risk for respiratory depression [7,8]. Because the use of fentanyl alone fails to provide sufficient sedation, midazolam is added in clinical practice to improve the quality of sedation. This step-by-step administration of low-dose fentanyl and midazolam, in combination with topical anesthesia, is a useful and safe method for sedated fiberoptic nasotracheal intubation.

In previous studies, it was reported that midazolam (0.05-2.7 mg/kg), propofol (1.0-2.7 mg/kg) and dexmede- tomidine (0.5-1.0 µg/kg) as the primary sedative agent generally describe in combination with opioid such as

Masanori Tsukamoto, et al

fentanyl (1.0-3.0 µg/kg), sufentanil (the target plasma concentration 0.3 ng/kg) or remifentanil (0.25-0.75 µg/kg) [5,6-9]. However, appropriate levels of sedation for safe awake intubation are very difficult to standardize because the required combination of anxiolysis and analgesia varies widely from case to case [6,10].

AUTHOR ORCIDs

Masanori Tsukamoto: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6848-0870 Takashi Hitosugi: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3963-541X Takeshi Yokoyama: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3017-8865

NOTE: There are no financial or other issues that might lead to conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

1. Prasanna D, Bhat S. Nasotracheal Intubation: An Overview. J Maxillofac Oral Surg 2014; 13: 366-72.

2. Dhasmana S, Singh V, Pal US. Awake Blind Nasotracheal Intubation in Temporomandibular Joint Ankylosis Patients under Conscious Sedation Using Fentanyl and Midazolam.

J Maxillofac Oral Surg 2010; 9: 377-81.

3. El-Boghdadly K, Onwochei DN, Cuddihy J, Ahmad I.

A prospective cohort study of awake fibreoptic intubation practice at a tertiary centre. Anaesthesia 2017; 72: 694-703.

4. Xue FS, Liu HP, He N, Xu YC, Yang QY, Liao X, et al. Spray-as-you-go airway topical anesthesia in patients with a difficult airway: a randomized, double-blind comparison of 2% and 4% lidocaine. Anesth Analg 2009;

108: 536-43.

5. Shen SL, Xie YH, Wang WY, Hu SF, Zhang YL.

Comparison of dexmedetomidine and sufentanil for con- scious sedation in patients undergoing awake fibreoptic nasotracheal intubation: a prospective, randomised and controlled clinical trial. Clin Respir J 2014; 8: 100-7.

6. Johnston KD, Rai MR. Conscious sedation for awake fibreoptic intubation: a review of the literature. Can J Anaesth 2013; 60: 584-99.

7. Tsukamoto M, Hirokawa J, Yokoyama T. Airway spray efficacy of local anesthetic with fiberscope. J Anesth 2017;

31: 639.

8. Kumar P, Kaur T, Atwal GK, Bhupal JS, Basra AK.

Comparison of Intubating Conditions using Fentanyl plus Propofol Versus Fentanyl plus Midazolam during Fibe- roptic Laryngoscopy. J Clin Diagn Res 2017; 11: 21-24.

9. Barends CR, Absalom A, van Minnen B, Vissink A, Visser A. Dexmedetomidine versus Midazolam in Procedural Sedation. A Systematic Review of Efficacy and Safety.

PLoS One 2017; 12: e0169525.

10. Dhasmana S, Singh V, Pal US. Awake blind nasotracheal intubation in temporomandibular joint ankylosis patients under conscious sedation using fentanyl and midazolam.

J Maxillofac Oral Surg 2010; 9: 377-81.

Medical adhesive related skin injury after dental surgery

Tae-Heung Kim

1, Jun-Sang Lee

1, Ji-Hye Ahn

2, Cheul-Hong Kim

2, Ji-Uk Yoon

3, Eun-Jung Kim

21Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, School of Dentistry, Pusan National University, Yangsan, Korea

2Department of Dental Anesthesia and Pain Medicine, Pusan National University Dental Hospital, Dental Research Institute, Yangsan, Korea

3Department of Anesthesia and Pain Medicine, Pusan National University Yangsan Hospital, Yangsan, Korea

An 87-year-old woman was referred for the extraction of residual teeth and removal of tori prior to prosthetic treatment. After surgery under general anesthesia, the surgical tape was removed to detach the bispectral index sensor and the hair cover. After the surgical tape was removed, skin injury occurred on the left side of her face. After epidermis repositioning and ointment application, a dressing was placed over the injury. Her wound was found to have healed completely on follow-up examination. Medical adhesive related skin injury (MARSI) is a complication that can occur after surgery and subjects at the extremes of age with fragile skin are at a higher risk for such injuries. Careful assessment of the risk factors associated with MARSI is an absolute necessity.

Keywords: Medical Adhesive; Skin Injury; Surgical Tape.

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/) which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Received: October 1, 2018•Revised: October 8, 2018•Accepted: October 10, 2018

Corresponding Author: Eun-Jung Kim, Department of Dental Anesthesia and Pain Medicine, Pusan National University Dental Hospital, Geumo-ro 20, Yangsan, Gyeongnam 626-787, Korea

Tel: +82-55-360-5370 Fax: +82-55-360-5369 Email: kejdream84@naver.com Copyrightⓒ 2018 Journal of Dental Anesthesia and Pain Medicine

INTRODUCTION

Medical Adhesive Related Skin Injury (MARSI) is a dermatological disorder in which erythema and/or other cutaneous abnormalities including, but not limited to, vesicles, bullae, erosions, or tears appear and persist for 30 min or more after removal of an adhesive [1]. MARSI can be caused by various types of adhesive products such as tape, dressing bandage, and electrodes after surgery.

It can occur in all ages but is more common in patients at the extremes of age with weak skin [2]. MARSI can lead to pain, increased risk of infection, scar formation, prolonged duration of treatment, patient complaints, and many discomforts that reduce a patient’s quality of life [3]. In order to prevent MARSI, the proper type of

adhesive tape should be applied, and special care should be taken in high risk patients. Here, we report a case of facial skin injury, caused by surgical tape, that was treated in our department.

CASE

An 87-year old woman visited our dental hospital for prosthetic treatment. She had residual teeth which could not be used as abutments for the denture. For prostho- dontic rehabilitation, removal of remaining teeth and full denture placement were planned. Therefore, she was referred to the department of Oral surgery for extraction of the residual teeth and tori removal prior to prosthetic treatment. She had hypertension and was taking amlo-

Tae-Heung Kim, et al

Fig. 1. Tape was removed and the skin peeled off.

Fig. 2. After 5 days, bruising is worsened, but secondary healing is occurring.

Fig. 3. After 12 days, bruising was fairly reduced.

dipine. The American Society of Anesthesiologists physical status of the patient was II. Preoperative laboratory findings and the chest X-ray image were normal. The electrocardiogram showed sinus rhythm with right bundle branch block and left anterior fascicular block. However, no significant abnormality was noted on echocardiography. Her skin was thin and inelastic due to aging, with extensive wrinkling in the face.

General anesthesia was induced for surgery and the patient was monitored. In addition, bispectral index (BIS)

monitoring was conducted for checking the depth of anesthesia and the BIS sensor was fixed using surgical drape tape (LobanTM2 incise drapes; 3M, St Paul, MN, USA). Surgical tape was attached from the bottom of the ear to the forehead for prevention of betadine drape and water. Approximately one hour after the surgery, she was reversed from the effects of the muscle relaxant using pyridostigmine 10 mg and glycopyrrolate 0.4 mg. After extubation, the surgical tape was removed to detach the BIS sensor and the hair cover. After the surgical tape was removed, skin injury occurred on the left side of her face. Along the site of attachment, 1.5 cm by width and 4 cm by length of her skin peeled off with the surgical tape. In addition, a red bruise appeared around the area of the surgical tape (Fig. 1). Immediately after reposi- tioning the epidermis, antibacterial ointment was applied and covered with non-adhesive foam dressing to maintain a moist wound environment. It was maintained for five days, and a repeat dressing was done during the next visit.

The epidermis was retained and secondary healing had initiated in the uncovered area. However, the bruising had worsened (Fig. 2). After realignment of the epidermal margin, ointment was applied and a dressing was placed.

She changed her dressing daily at home by herself and visited the clinic a week later. The wound had healed well compared to the first visit at outpatient clinic after

surgery. The area of bruising had reduced considerably.

No evidence of infection was seen (Fig. 3). There was no problem in the intra-oral surgical site and stitch out was performed. She decided to continue performing the dressing at home by herself.

DISCUSSION

MARSI is estimated to occur in at least 1.5 million patients annually in the United States [4]. Skin injuries caused by adhesive tapes occur in a variety of surgical situations. There are intrinsic and extrinsic factors related to the skin injury. Intrinsic factors include extremes of age: neonate or elderly, race, dermatologic conditions, underlying medical conditions, malnutrition, and dehy- dration. Extrinsic factors include skin dryness, prolonged exposure to moisture, certain medications (i.e., anti- inflammatory agents, anticoagulants, chemotherapeutic agents, long-term corticosteroid use), radiation therapy, photo-damage, improper choice of tape, and repeated taping [5-7]. In case of this patient, she was aged and her skin was very thin and loose. In addition, she was poorly nourished because her remaining teeth were not in good condition. Extrinsic factors which had an effect on her skin injury were improper tape selection and tape removal with excessive force.

According to literature, the types of skin injury include skin stripping, blisters, skin tears, allergic dermatitis, and folliculitis, but the treatment for all these is similar [8].

After an initial assessment to determine the severity of the skin injury, the wound should be cleaned with saline to remove adhesive residue and any source of infection.

Afterward, ointment and dressing should be applied to create a moist wound environment to aid in healing. If a skin injury does not respond to conservative manage- ment within seven days, it is appropriate to consider consultation with a dermatologist [1]. In this case, secon- dary healing was complete five days later and local application of antibacterial ointment with a wet dressing was helpful.

In our case, using the strong adhesive surgical tape and its removal with excessive force and not considering the age of the patient, predisposed the patient to skin injury and these were preventable factors. In order to prevent MARSI, it is important to check the age and skin condition of the patient to enable the appropriate adhesive tape choice and ensure adequate care for gentle removal.

It is also important to know the patient's general condition and allergy history. If the patient’s skin is sensitive, it is better to use silicone tape, which is a weak adhesive [9]. Most adhesive tapes used in anesthetic practice are acrylate based. Silicone tapes have lower surface tension to make rapid contact with the entire skin surface and maintain a constant level of adherence [10]. In addition, we should loosen the edges of the tape and separate the tape from the skin with a gentle force and remove the adhesive product at a low angle and slowly back over itself in the direction of hair growth, keeping it horizontal and close to the skin surface [1,11].

This case report emphasizes the risk of MARSI. There are various risk factors associated with MARSI, but most factors are preventable. The selection, application, and careful removal of the adhesive tape are essential for uncomplicated postoperative care in patients.

AUTHOR ORCIDs

Tae-Heung Kim: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1361-4007 Jun-Sang Lee: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9921-4778 Ji-Hye Ahn: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8811-8465 Cheul-Hong Kim: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1536-9460 Ji-Uk Yoon: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3971-2502 Eun-Jung Kim: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4982-9517

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS: This study was supported by the 2017 Clinical Research Grant, Pusan National University Dental Hospital.

NOTE: There are no financial or other issues that might lead to conflict of interest.

Tae-Heung Kim, et al

REFERENCES

1. McNichol L, Lund C, Rosen T, Gray M. Medical adhesives and patient safety: state of the science: consensus statements for the assessment, prevention, and treatment of adhesive-related skin injuries. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs 2013; 32: 267-81.

2. Lober CW, Fenske NA. Cutaneous aging: effect of intrinsic changes on surgical considerations. South Med J 1991; 84:

1444-6.

3. Cutting KF. Impact of adhesive surgical tape and wound dressings on the skin, with reference to skin stripping.

J Wound Care 2008; 17: 157-62.

4. Groom M, Shannon RJ, Chakravarthy D, Fleck CA. An evaluation of costs and effects of a nutrient-based skin care program as a component of prevention of skin tears in an extended convalescent center. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs 2010; 37: 46-51.

5. LeBlanc K, Baranoski S, Skin Tear Consensus Panel Members. Skin tears: state of the science: consensus statements for the prevention, prediction, assessment, and

treatment of skin tears(c). Adv Skin Wound Care 2011;

24: 2-15.

6. Conway J, Whettam J. Adverse reactions to wound dressings. Nurs Stand 2002; 16: 52-4, 56, 58 passim.

7. Norris P, Storrs FJ. Allergic contact dermatitis to adhesive bandages. Dermatol Clin 1990; 8: 147-52.

8. Bryant RA. Types of skin damage and differential diagnosis.

In: Bryant R, Nix D, eds. Acute & Chronic wounds: Current Management Concepts. 4th ed. St Louis, MO: Elsevier Mosby 2012: 83-107.

9. Zeng LA, Lie SA, Chong SY. Comparison of Medical Adhesive Tapes in Patients at Risk of Facial Skin Trauma under Anesthesia. Anesthesiol Res Pract 2016; 2016:

4878246.

10. Grove GL, Zerweck CR, Houser TP, Smith GE, Koski NI. A randomized and controlled comparison of gentleness of 2 medical adhesive tapes in healthy human subjects.

J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs 2013; 40: 51-9.

11. LaVelle BE. Reducing the risk of skin trauma related to medical adhesives. Manag Infect Control 2004; 182:

1289-94.