의

의

의학

학

학 석

석

석사

사

사학

학

학위

위

위 논

논

논문

문

문

C

C

Co

o

om

m

mp

p

pl

l

li

i

ic

c

ca

a

at

t

ti

i

io

o

on

n

ns

s

si

i

in

n

n

L

L

La

a

ap

p

pa

a

ar

r

ro

o

os

s

sc

c

co

o

op

p

py

y

y-

-

-A

A

As

s

ss

s

si

i

is

s

st

t

te

e

ed

d

dG

G

Ga

a

as

s

st

t

tr

r

re

e

ec

c

ct

t

to

o

om

m

my

y

y:

:

:

M

M

Mu

u

ul

l

lt

t

ti

i

iv

v

va

a

ar

r

ri

i

ia

a

at

t

te

e

eA

An

A

n

na

a

al

l

ly

y

ys

s

si

is

i

s

so

o

of

f

f3

3

30

0

00

0

0

C

C

Co

o

on

n

ns

s

se

e

ec

c

cu

u

ut

ti

t

i

iv

v

ve

e

eC

Ca

C

a

as

s

se

e

es

s

s

아

아

아 주

주

주 대

대

대 학

학

학 교

교

교 대

대

대 학

학

학 원

원

원

의

의

의 학

학

학 과

과

과

박

박

박 종

종

종 민

민

민

Complications

Complications

Complications

Complications in

in

in Laparoscopy-Assisted

in

Laparoscopy-Assisted

Laparoscopy-Assisted

Laparoscopy-Assisted Gastrectomy:

Gastrectomy:

Gastrectomy:

Gastrectomy:

Multivariate

Multivariate

Multivariate

Multivariate Analysis

Analysis

Analysis

Analysis of

of

of

of 300

300

300

300 Consecutive

Consecutive

Consecutive

Consecutive Cases

Cases

Cases

Cases

by

Jong-Min Park

A Dissertation Submitted to The Graduate School of Ajou University

in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of

MASTER OF MEDICAL SCIENCES

Supervised by

Sang-Uk Han, M.D., Ph.D.

Department

Department

Department

Department of

of

of

of Medical

Medical

Medical Sciences

Medical

Sciences

Sciences

Sciences

The

The

The

The Graduate

Graduate

Graduate

Graduate School,

School,

School,

School, Ajou

Ajou

Ajou

Ajou University

University

University

University

박

박

박종

종

종민

민

민의

의 의

의

의

의학

학

학 석

석

석사

사

사학

학

학위

위

위 논

논

논문

문

문을

을

을 인

인

인준

준

준함

함

함.

.

.

심

심

심사

사위

사

위

위원

원

원장

장

장

한 상

한

한

상

상 욱

욱

욱

인

인

인

심

심

심 사

사

사 위

위

위 원

원

원

조

조

조 용

용

용 관

관

관

인

인

인

심

심

심 사

사

사 위

위

위 원

원

원

김

김

김 진

진

진 홍

홍

홍

인

인

인

아

아

아 주

주

주 대

대

대 학

학

학 교

교

교 대

대

대 학

학

학 원

원

원

2

2

20

0

00

0

08

8

8년

년

년 6

6

6월

월

월 2

2

23

3

3일

일

일

- ASTRACT -

Complications in Laparoscopy-Assisted Gastrectomy: Multivariate

Analysis of 300 Consecutive Cases

Background : Complications during laparoscopy-assisted gastrectomy (LAG) are not

significantly different from those of the open gastrectomy. However, additional risks related with abdominal access, pneumoperitoneum, and special electrosurgical instruments result in increased incidence of complications in LAG. In this study, we analyzed causes and risk factors linked to postoperative morbidity.

Methods : We retrospectively reviewed data of 300 patients who underwent consecutive

LAG for gastric cancer at our department from May 2003 to October 2006. Among the 300 patients, total gastrectomy was performed in 42 patients, distal gastrectomy in 258 patients, and proximal gastrectomy in 3 patients. Clinical and operative data obtained included body mass index, medical comorbidities, history of previous abdominal surgery, operative time, type of surgery, extent of lymph node dissection according to the Japanese Guideline, number of retrieved lymph nodes and lymph node metastasis, additional operative procedure, depth of tumor invasion and stage. Outcome data consisted of mortality, major morbidities, and postoperative hospital stay. The 300 patients were divided into 2 periods; 50 cases in the 1st period and 250 cases in the 2nd period.

Results : Postoperative complications were developed in 61 cases (20.3%); wound infection

(4.3%), leakage in 3 (1.0%), acute pancreatitis in 2 (0.7%), pulmonary complication in 4 (1.3%), renal complication in 4 (1.3%) and cardiac complication in 2 (0.7%). The 30-day mortality rate was 0.7% (n=2). Gender, operative period, comorbidity, and operative times were proved to be important risk factors in univariate analaysis. In multivariate analysis, cormobidity and operative period were proved to be important risk factors.

Conclusions : The data suggest that LAG can be performed with acceptable perioperative

complication rates. Experience of surgeon and careful patient selection determined optimal patient outcomes.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

ABSTRACT ··· i

TABLE OF CONTENTS ··· iii

LIST OF FIGURES ··· iv

LIST OF TABLES ··· v

I. INTRODUCTION ··· 1

II. MATERIALS AND METHODS ··· 3

III. RESULTS ··· 6

IV. DISCUSSION ··· 18

V. CONCLUSION ··· 22

REFERENCES ··· 23

LIST OF FIGURES

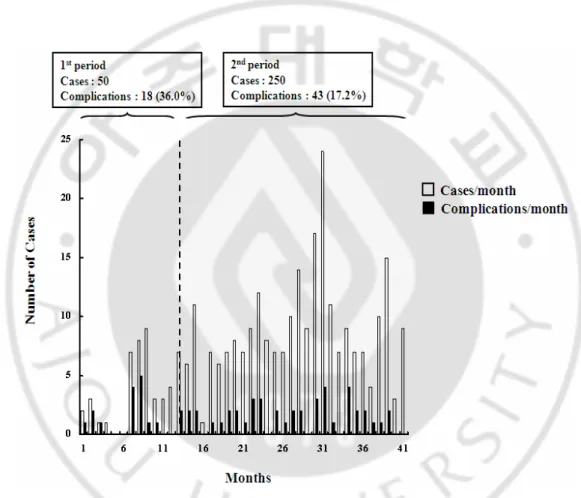

Fig. 1. The numbers of performed LAG and complication in each month. The cases of LAG increased, whereas the complication rate decreased. ··· 6

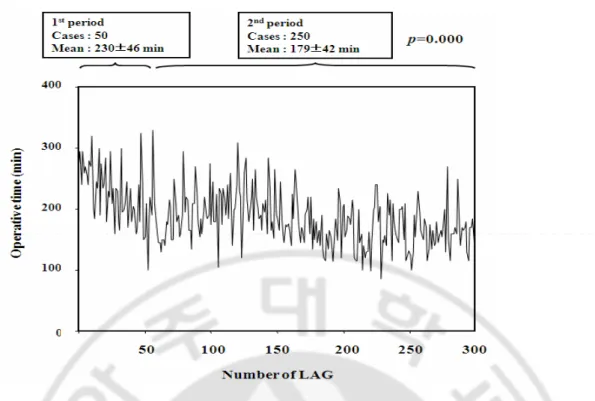

Fig. 2. Operative time of each LAG case. A considerable decrease was observed in

operating time until 50 cases, but there was a slight increase after 50 cases, followed by an another decrease, then reaching a plateau. ··· 11

LIST OF TABLES

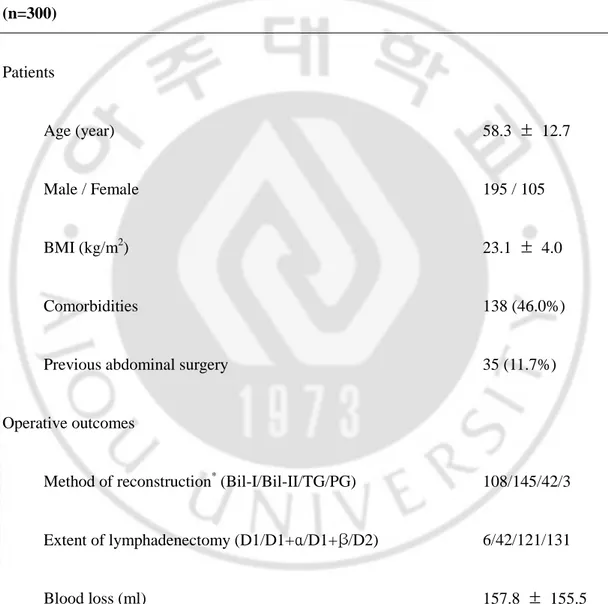

Table 1. Characteristics, pathologic findings and operative outcomes of LAG patients

(n=300) ··· 7

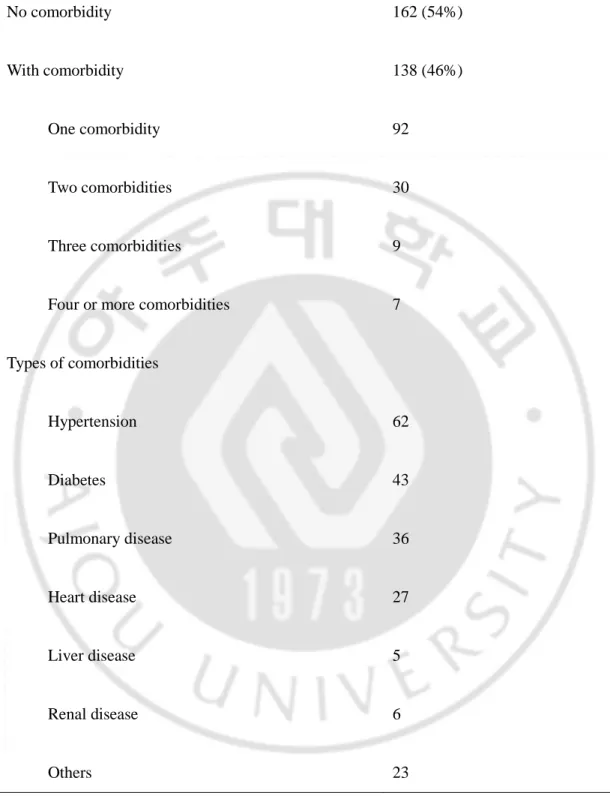

Table 2. Incidence of comorbidities(n=300) ··· 9

Table 3. Incidence of postoperative complications(n=300) ··· 12

Table 4. Incidence of postoperative complications according to the period(n=300) ··· 13

Table 5. Univariate analysis of factors associated with complications ··· 14

I. INTRODUCTION

The laparoscopic application to general surgical procedures began in the latter 1980s (Cuschieri et al, 1991). From then, there has been an explosion of interest and training in the various aspects of minimal-access surgery for general surgeons. Since its introduction in 1991 (Kitano et al, 1994), laparoscopy-assisted gastrectomy (LAG) has gained widespread, international acceptance among surgeons as one of the best treatments for early gastric cancer (EGC). LAG has several advantages over conventional open surgery, including less invasiveness, less pain, earlier recovery, and better cosmesis (Adachi et al, 2000). In general, complications during LAG are not significantly different from those of the open gastrectomy. However, additional risks related with abdominal access, pneumoperitoneum, and special electrosurgical instruments result in increased incidence of complications in LAG. LAG is a complex and time-consuming procedure, because the procedure should include enough surgical margins and the number of dissected lymph nodes should be equivalent to those in conventional open gastrectomy. According to a survey conducted by the Japan Society for Endoscopic Surgery, the incidence of complications after laparoscopy-assisted distal gastrectomy (LADG) are 9.7%; the major complications are bleeding, gastric stasis, anastomosis leakage, and wound infection (Kitano and Shiraishi, 2004). In published literatures, the incidence of postoperative complications in LAG ranged from 5.4 to 23.3 % (Yano et al, 2001; Weber et al, 2003; Mochiki et al, 2005; Noshiro et al, 2005; Kitano et al 2002; Kim et al, 2005; Huscher et al, 2005), however, the numbers of patients of these studies were less than 50. To perform extensive lymph node dissection with minimal

morbidity during LAG, surgeons should complete the learning curve. We suggested that advanced procedures and extension of indications in LAG should be delayed until a learning curve is completed under the target failure rate in multidimensional learning curve (Jin et al, 2007). Therefore, much larger number of cases are needed for risk analysis about complications in LAG. In this study, we analyzed causes and risk factors related with postoperative morbidity in 300 cases who underwent LAG, based on the data derived from a single center by one surgeon.

II. MATERIALS AND METHODS

We retrospectively reviewed database of 300 patients, who underwent consecutive LAG for EGC from May 2003 to October 2006 at Ajou University Hospital in Suwon, Korea. Among them, total gastrectomy was performed in 42 patients, distal gastrectomy in 255 patients, and proximal gastrectmy in 3 patients. There was no conversion to open surgery. The review board of the Ajou University Medical Center approved the protocol used for LAG with systemic lymphadenectomy in early gastric cancer patients, and written informed consent was obtained from every patient that agreed to LAG with systemic lymphadenectomy. The indication for LAG at our hospital is a mucosal or submucosal lesion with or without lymph node metastasis on preoperative endoscopic ultrasonography and abdominal CT. Cases with mucosal lesions suitable for endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) were excluded. The indication for EMR is mucosal lesion with a size less than 2cm and no ulcer.

The LADG procedure was as follows. After a subumbilical trocar was inserted, the other four ports were added under laparoscopic observation. The greater omentum was divided with preservation of the distal portion and dissected toward the lower end of the spleen by using laparoscopic coagulation shears (LCS; Ethicon Endo-Surgery, Cicinnati, OH, USA). Blunt dissection then was advanced toward the right side to detach the subpyloric lymph nodes from mesocolon. The right gastroepiploic vessels were isolated and divided at their roots. The lesser omentum was opened, and the right gastric artery was divided. Next, the duodenum was transected just distal to the pyloric ring, using endoscopic linear stapler

(ETS45; Ethicon Endo-Surgery, Cincinnati, OH, USA). After retraction of the distal stomach cephalad, the suprapyloric lymph nodes and lymph nodes along the common hepatic artery and hepatoduodenal ligament were also dissected. Then, the left gastric vein was exposed and divided at the root. The left gastric artery then was exposed and retracted upward, while lymph nodes were dissected around the celiac artery and proximal splenic artery. The left gastric artery was isolated and divided after double clipping. Perigastric lymph nodes were dissected along the lesser curvature up to the esophagocardial junction. In Billroth I reconstruction, the right upper trocar incision was extended to 4-5cm transversely, and the stomach was taken out for resection and anastomosis. Gastroduodenostomy was performed using a circular stapler (Proximate CDH 29; Ethicon Endo-Surgery, Cincinnati, OH, USA). On the other hand, a 3-4 cm midline skin incision was extended from the epigastric trocar incision in Billroth II reconstruction. Gastrojejunostomy was carried out by hand sewing. In total gastrectomy, a 5 cm vertical incision at the epigastrium was made. After pulling out the stomach from the mini-laparotomy, a purse-string device was introduced to the abdominal esophagus, the abdominal esophagus was transected at the distal side of the purse-string suture device, and stomach was removed. The anvil head of a circular stapler (Proximate CDH25; Ethicon Endo-Surgery, Cincinnati, OH, USA) was inserted into the esophagus, and the purse-string suture was closed. The jejunum was divided at a point 30 cm distal to the ligament of Treitz. The point had already been marked laparoscopically. Reconstruction was done by Roux-en-Y method. First, the jejunojejunal anastomosis was performed extracorporeally by hand sewing. Then, the shaft of the circular stapler was introduced into the distal segment of the jejunum and an end-to-side esophagojenunostomy was made. The

jejunal stump was closed with a 45-mm endoscopic linear stapler (ETS45; Ethicon Endo-Surgery, Cincinnati, OH, USA) through the mini-laparotomy under direct vision.

All patients were routinely managed using a standardized postoperative protocol as follows : (1) Removal of nasogastric tube at postoperative day one if no bleeding was checked; (2) sips of water two days after the operation; (3) clear liquid diet after first flatus; and (4) discharge of the patients after tolerance of a soft diet for two more days.

Clinical and operative data obtained included body mass index (BMI), medical comorbidities, history of previous abdominal surgery, tumor location, operative time, type of surgery, type of reconstruction, extent of lymph node dissection according to the Japanese Guideline (D1: dissection of all perigastric lymph nodes of the relevant part of the stomach, D1 + α: D1 plus the left gastric artery nodes, D1 + β:D1 plus the left gastric artery, the common hepatic artery and the celiac artery nodes, D2: standard D2 gastrectomy), number of retrieved lymph nodes and lymph node metastasis, additional operative procedures, tumor size, depth of tumor invasion and stage. Outcome data consisted of mortality, major morbidities and postoperative hospital stay. For assessing surgeon’s experience, the 300 patients were divided into 2 periods; 50 cases in the 1st period and 250 cases in the 2nd period.

Statistical univariate analysis was performed using chi-squared testing with statistical significance at the 95% level, whereas multivariate analysis was performed using logistic regression analysis.

III. RESULTS

The study cohort consisted of 300 consecutive patients who underwent LAG during the first 3.5 years in the author’s laparoscopic era. No patient was excluded from the analysis. In the first twelve months, only a few cases underwent LAG. Subsequently, however, the number of LAG reached about five or more cases per month (Fig. 1)

Fig. 1. The numbers of performed LAG and complication in each month. The cases of

Patients’ characteristics, pathologic results and operative outcomes are summarized in Table 1. The mean age was 58 years, and the majority of patients were men. The mean patient body mass index was 23.1 kg/m2. About half the patients had medical comorbidities, such as hypertension, pulmonary disease, diabetes mellitus, coronary heart disease, liver disease, and renal disease (Table 2).

TABLE 1. Characteristics, pathologic findings and operative outcomes of LAG patients

(n=300) Patients Age (year) 58.3 ± 12.7 Male / Female 195 / 105 BMI (kg/m2) 23.1 ± 4.0 Comorbidities 138 (46.0%)

Previous abdominal surgery 35 (11.7%)

Operative outcomes

Method of reconstruction* (Bil-I/Bil-II/TG/PG) 108/145/42/3

Extent of lymphadenectomy (D1/D1+α/D1+β/D2) 6/42/121/131

Operative time (min) 188.2 ± 46.5

Hospital stay (day) 10.5 ± 5.9

Pathologic results

Retrieved LN number 29.4 ± 12.2

T stage (Mucosa/Submucosa/Proper muscle/Subseroa/Serosa) 153/99/28/14/6

N stage† (N0/N1/N2) 247/50/3

Stage‡ (IA/IB/II/IIIA/IIIB/IV) 225/47/20/7/0/1

Data represent mean ± SD or number; BMI, body mass index. *Method of reconstruction; Bil-I, Billroth I; Bil-II,Billroth II; TG, total gastrectomy; PG, proximal gastrectomy. †N stage is classified according to the Guidelines of the Japanese Gastric Cancer Association. ‡Stage is classified by the 1997 UICC staging.

TABLE 2. Incidence of comorbidities(n=300) No comorbidity 162 (54%) With comorbidity 138 (46%) One comorbidity 92 Two comorbidities 30 Three comorbidities 9

Four or more comorbidities 7

Types of comorbidities Hypertension 62 Diabetes 43 Pulmonary disease 36 Heart disease 27 Liver disease 5 Renal disease 6 Others 23

Among them, 46 patients had two or more comorbidities. 35 patients had a history of abdominal surgery, including ulcer perforation, liver trauma, small bowel resection, cholecystectomy, hysterectomy, and appendectomy. Distal gastrectomy was performed in 255 patients for tumors located in the middle or distal third of the stomach; Billroth I gastroduodenostomy (36.0%) or Billroth II gastrojejunostomy (48.3%) were performed for reconstruction. 45 patients had tumors in the upper third of the stomach, which needed total or proximal gastrectomy. Among the 300 patients, 272 (90.7%) patients were stage I. D1 (2.0%) or D1 + α (14.0%) lymph node dissection was performed frequently for selected patients with advanced age or significant medical comorbidities. With accumulated experience, D1+ β (40.3%) and D2 (43.7%) dissection became technically feasible, and were more frequently used in the later period. But, we tried to do D2 dissection as early period as possible. There were no statistical differences between the two periods in the ratio of the extent of lymph node dissection.The mean retrieved number of lymph nodes was 29.4 and mean blood loss was 157.8 ml. In this study, the mean operative time of LAG was 188.2 minutes. Figure 2 shows the trend in operative time; initially, the operative time was longer than 250 minutes, but decreased to 200 minutes after about 50 cases. Operative time varied greatly, most likely due to different types of surgery and additional procedures. Mean hospital stay was 10.5 days.

Fig. 2. Operative time of each LAG case. A considerable decrease was observed in

operating time until 50 cases, but there was a slight increase after 50 cases, followed by an another decrease, then reaching a plateau.

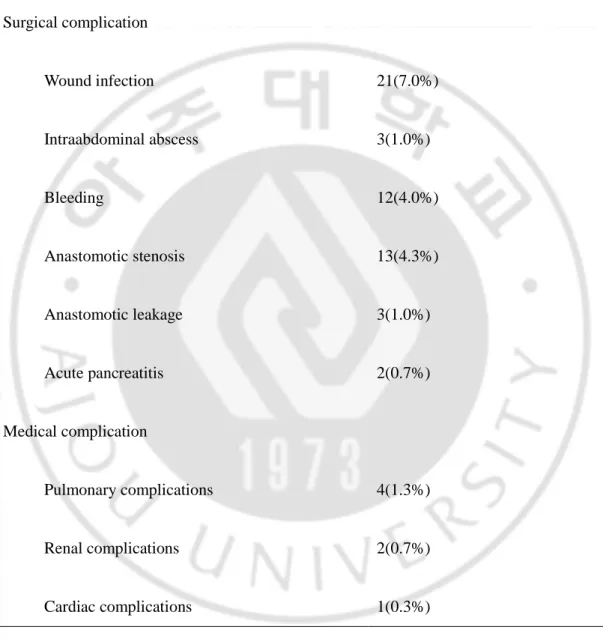

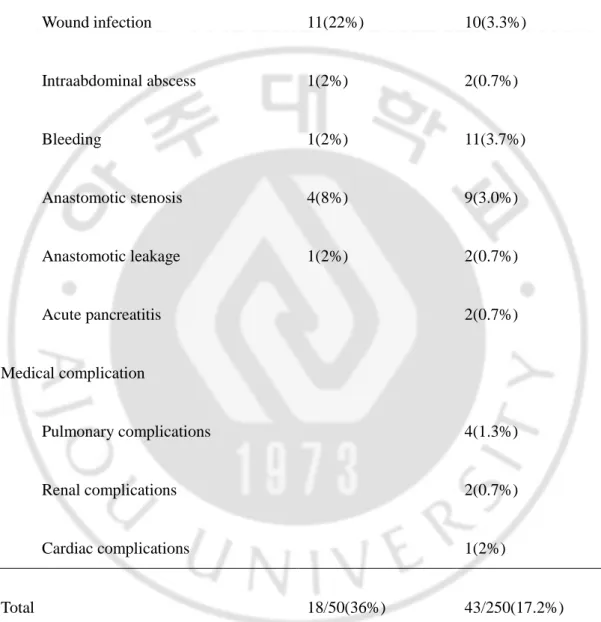

The 30-day mortality rate was 0.7% (n=2); one died of pancreatitis and the other of acute myocardial infarction. Postoperative complications developed in 61 cases (20.3%); wound infection in 21 (7.0%), intraabdominal abscess in 3 (1.0%), bleeding in 12 (4.0%), stenosis in 13 (4.3%), leakage in 3 (1.0%), acute pancreatitis in 2 (0.7%), pulmonary complication in 4 (1.3%), renal complication in 4 (1.3%) and cardiac complication in 2 (0.7%)(Table 3). Table 4 compares the complications in the 1st period with those in the 2nd period. The complications in the 1st period were mainly surgical complications such as wound infection. In the 2nd period, the rate of surgical complication decreased, but the rate of medical complication

associated with comorbidity increased. Figure 1 shows the numbers of operations and complications each month. The cases of LAG increased, but the complication rate decreased.

TABLE 3. Incidence of postoperative complications(n=300)

Surgical complication Wound infection 21(7.0%) Intraabdominal abscess 3(1.0%) Bleeding 12(4.0%) Anastomotic stenosis 13(4.3%) Anastomotic leakage 3(1.0%) Acute pancreatitis 2(0.7%) Medical complication Pulmonary complications 4(1.3%) Renal complications 2(0.7%) Cardiac complications 1(0.3%) Total 61/300(20.3%)

TABLE 4. Incidence of postoperative complications according to the period(n=300)

Operation period 1st period(n=50) 2nd period(n=250)

Surgical complication Wound infection 11(22%) 10(3.3%) Intraabdominal abscess 1(2%) 2(0.7%) Bleeding 1(2%) 11(3.7%) Anastomotic stenosis 4(8%) 9(3.0%) Anastomotic leakage 1(2%) 2(0.7%) Acute pancreatitis 2(0.7%) Medical complication Pulmonary complications 4(1.3%) Renal complications 2(0.7%) Cardiac complications 1(2%) Total 18/50(36%) 43/250(17.2%)

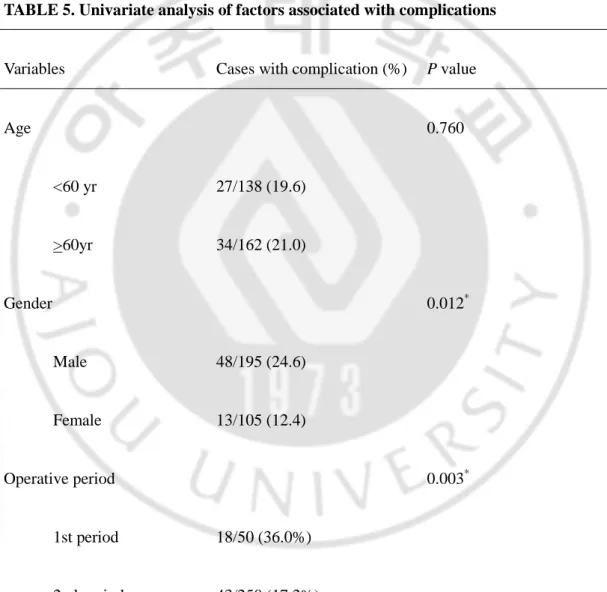

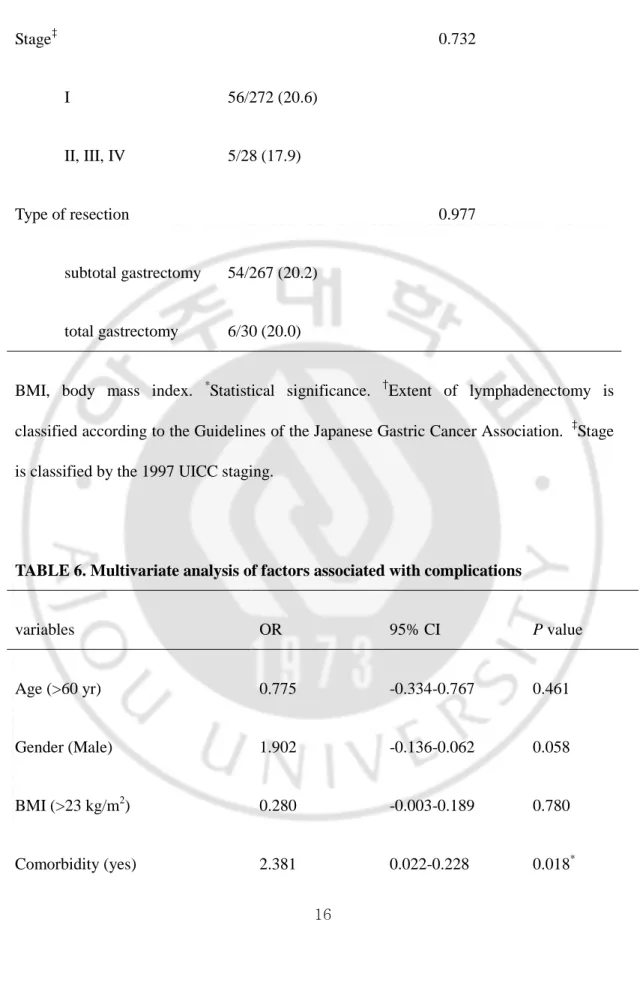

In univariate analysis of the factors associated with complication, gender, operative period, comorbidity, and operative time were proved to be important risk factors, wheras age, BMI, combined operation, extent of lymphadenectomy, stage, and type of resection were not serious risk factors(Table 5). In multivariate analysis, cormobidity and operative period were proved to be important risk factors(Table 6).

TABLE 5. Univariate analysis of factors associated with complications

Variables Cases with complication (%) P value

Age 0.760 <60 yr 27/138 (19.6) >60yr 34/162 (21.0) Gender 0.012* Male 48/195 (24.6) Female 13/105 (12.4) Operative period 0.003* 1st period 18/50 (36.0%) 2nd period 43/250 (17.2%)

BMI (kg/m2) 0.670 < 23 28/145 (19.3) > 23 33/155 (21.3) Comorbidity 0.046* No 26/162 (16.0) Yes 35/138 (25.4)

Operative time (min) 0.017*

< 180 22/149 (14.8) > 180 39/151 (25.8) Combined operation 0.512 No 57/274 (20.8) Yes 4/26 (15.4) Extent of lymphadenectomy† 0.494 < D2 32/169 (18.9) D2 29/131 (22.1)

Stage‡ 0.732 I 56/272 (20.6) II, III, IV 5/28 (17.9) Type of resection 0.977 subtotal gastrectomy 54/267 (20.2) total gastrectomy 6/30 (20.0)

BMI, body mass index. *Statistical significance. †Extent of lymphadenectomy is classified according to the Guidelines of the Japanese Gastric Cancer Association. ‡Stage is classified by the 1997 UICC staging.

TABLE 6. Multivariate analysis of factors associated with complications

variables OR 95% CI P value

Age (>60 yr) 0.775 -0.334-0.767 0.461

Gender (Male) 1.902 -0.136-0.062 0.058

BMI (>23 kg/m2) 0.280 -0.003-0.189 0.780

Operation time (>180 min) 1.449 -0.026-0.169 0.148

Combined operation (one more) 1.136 -0.260-0.070 0.257

Extent of lymphadenectomy (D2) 0.558 -0.067-0.120 0.577

Stage (>II) 0.422 -0.191-0.124 0.674

Type of resection (subtotal or total)

0.184 -0.129-0.156 0.854

Operation period (1st vs. 2nd) 2.519 0.036-0.293 0.012*

IV. DISCUSSION

LAG is less invasive than conventional open gastrectomy. It leads to a faster recovery of gastrointestinal functions and a reduction of pain and, furthermore, there is no significant differences in complication and mortality rate between the two. Recently, randomized controlled trial by Huscher et al (Huscher et al, 2005) and prospective multi-center trial by Kitano et al (Kitano et al, 2007) showed that EGC patients who underwent LAG showed five-year survival rates, indicating excellent oncologic outcomes. Together with the development of operation skills and operation devices, LAG is being used in expanded indication, including more expanded lymph node dissection (D1+ or D2), total gastrectomy, and advanced cancer. However, there are not enough studies on the factors that increase complications when such complicated procedure is performed.

Several studies which examined complication and mortality rates related to LAG, LAG shows similar or better results when compared with conventional open gastrectomy. Huscher et al (Huscher et al, 2005) in their randomized controlled study observed that mortality and morbidity rates related to LAG were 3.3 % and 26.7 %, respectively, showing no significant difference from those of open gastrectomy 6.7 % and 27.6 %, respectively; Kitano et al (Kitano et al, 2007) in their Japanese multi-center trial on 1294 patients of early gastric cancer found that mortality and morbidity rates were 0 % and 14.8 %, respectively. However, in the study of Kitano et al, patients with cancer in other organs, advanced cancer, previous upper abdominal laparotomy or organ insufficiency were not included; In the study on 140 gastric cancer patients, Kim et al (Kim et al, 2007) found that overall mortality and

morbidity rates were 0.7 % and 18.6 %, respectively; In the meta-analysis into LADG and conventional open distal gastrectomy, Hosono et al (Hosono et al, 2006) showed that LADG excelled in terms of complication and there were no significant differences in anastomosis, pulmonary, wound complication, and mortality.

This study constitutes a short-term outcome for gastric cancer patients who underwent LAG by a single operator at a single center, and aimed to elucidate the complication-related risk factors via univariate and multivariate analyses, and to emphasize the need for a learnig curve to guarantee safety which is acceptable for performing complicated procedures such as LAG, or selecting proper patients for LAG.

In this study, 61 (20.3 %) out of 300 patients developed complications after operation and, among these patients, 18 (36 %) out of 50 patients developed complications during the 1st period, before completing the learning curve, and 43(17.2 %) out of 250 patients developed complications during the 2nd period, after completion of the learning curve. In the univariate analysis into risk factors that lead to development of complications, male patients, patients with comorbidity, longer operative time, and 1st period had increasing possibilities of developing complications. When multivariate analysis was made based on the univariate analysis, we found a meaningful increase in the development of complications in cases with comorbidity and in the 1st period.

Generally speaking, all patients for whom it is possible to administer general anesthesia can be considered for laparotomy and laparoscopic operation. However, we need to be cautious in choosing laparotomy or laparoscopic operation, because pneumoperitoneum may influence pulmonary capacity or cardiac reserve in patients with severe pulmonary or cardiac

disease. We also found that the development of complications significantly increased in patients with comorbidity. Furthermore, there were cases in which patients with senility and many comorbidities had to stay in the hospital longer than expected, because they showed delayed recovery of general conditions, even without the development of particular complications.

There have been several studies on the effect of comorbidity on operative risk: Zingmond et al (Zingmond et al, 2003) stated that after operations on colorectal cancer patients, patient characteristics, such as age, comorbidiy, and acuity of surgery are important factors for serious medical and surgical complications; Jamal et al (Jamal et al, 2005) observed in their study on gastric bypass of 1465 morbid obesity patients, that there was a much greater number of early postoperative complications in patients with major comorbidity than with those who had minor comorbidity or patients without comorbidity, and that the difference was more than 10 times in mortality; Matin et al (Matin et al, 2003) reported that, in cases of laparoscopic renal and adrenal surgery patients by multivariate analysis, the lower the comorbidiy index, the less the patients experience postoperative complications. The study also showed that those who were older than 65 years could be a factor in delaying the hospital stay, however it did not increase the operative complication risk, thus proving correlation between comorbidity and operative risks.

The present study observed a considerable decrease of complication rates after the 1st period (first 50 casses), and also an improvement in operative time. Several studies on learning curve of laparoscopy used conversion rate, operation time, blood loss, major morbidity, and mortality as important parameters. Eto et al (Eto et al,2006), in their study on

laparoscopic adrenalectomy, reported that open conversion and transfusion were not needed after operation of 42 cases; Kanno et al (Kanno et al, 2006), in their research on laparoscopic nephrectomy, stated that the more experience a surgeon has, the less complication rate and operation time grew, and the numbers revealed a notable decrease after 50 cases; Vaisbuch et al (Vaisbuch et al, 2006), in their comparative study on laparoscopic hysterectomy and total abdominal hysterectomy, observed that the more experience a surgeon has, the bigger the decrease in the operation time, complication rate and length of hospital stay; Reissman et al (Reissman et al, 1996), in their study on laparoscopic colorectal surgery of 100 cases, stated that learning curve and types of procedures affected the morbidity; Kim et al (Kim et al, 2005), in their study on learning curve of LADG, observed a result similar to the present study, showing a notable improvement in operating time after operation of 50 cases.

What was notable in this study is the fact that a considerable decrease was found in terms of operative time and development of complication until 50 cases, but there was a slight increase after 50 cases, followed by an another decrease, then reaching a plateau (Fig. 2). This is most likely due to the extension of patient selection, such as patients with many comorbidities, advanced case and total gastrectomy, and also the extension of lymph node dissection such as D1+β or D2 dissection after the learning curve.

V. CONCLUSION

In the present study, we found that important risk factors for complications of LAG are patient’s comorbidity and surgeon’s experiences: The more a patient carries comorbidities, especially in the case of marginal pulmonary capacity or cardiac reserve, the more a surgeon should be concerned about the selection of patients. In the case of LAG operations, we found that at least 50 cases worth of experience could bring improvements of complications and operation time. In the early period, caution needs to be taken in patient selection and a trial of advanced procedures. Furthermore, in order to overcome learning curve early, education and training for surgeons are needed in addition to accumulation of cases.

REFERENCES

1. Adachi Y, Shiraishi N, Shiromizu A, Bandoh T, Aramaki M, Kitano S: Laparoscopy-assisted Billroth I gastrectomy compared with conventional open gastrectomy. Arch Surg 135(7): 806-810, 2000

2. Cuschieri A, Dubois F, Mouiel J, Mouret P, Becker H, Buess G, Trede M, Troidl H: The European experience with laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Am J Surg 161(3): 385-387, 1991

3. Eto M, Harano M, Koga H, Tanaka M, Naito S: Clinical outcomes and learning curve of a laparoscopic adrenalectomy in 103 consecutive cases at a single institute. Int J Urol 13: 671-676, 2006

4. Hosono S, Arimoto Y, Ohtani H, Kanamiya Y: Meta-analysis of short-term outcomes after laparoscopy-assisted distal gastrectomy. World J Gastroenterol 12(47): 7676-7683, 2006

5. Huscher CGS, Mingoli A, Sgarzini G, Sansonetti A, Paola MD, Recher A, Ponzano C: Laparoscopic versus open subtotal gastrectomy for distal gastric cancer. Five-year results of a randomized prospective trial. Ann Surg 241: 232-237, 2005

6. Jamal MK, DeMaria EJ, Johnson JM, Carmody BJ, Wolfe LG, Kellum JM, Meador JG: Impact of major co-morbidities on mortality and complications after gastric bypass. Surg Obes Relat Dis 1: 511-516, 2005

7. Jin SH, Kim DY, Kim H, Jeong IH, Kim MW, Cho YK, Han SU: Multidimensional learning curve in laparoscopy-assisted gastrectomy for early gastric cancer. Surg Endosc 21: 28-33, 2007

8. Kanno T, Shichiri Y, Oida T, Kanamaru H, Takao N, Shimizu Y: Complications and learning curve for a laparoscopic nephrectomy at a single institution. Int J Urol 13: 101-104, 2006

9. Kim MC, Kim KH, Kim HH, Jung GJ: Comparison of laparoscopy-assisted by conventional open distal gastrectomy and extraperigastric lymph node dissection in early gastric cancer. J Surg Oncol 91: 90-94, 2005

10. Kim MC, Jung GJ, Kim HH: Morbidity and mortality of laparoscopy-assisted gastrectomy with extraperigastric lymph node dissection for gastric cancer. Dig Dis Sci 52: 543-548, 2007

11. Kim MC, Jung GJ, Kim HH: Learning curve of laparoscopy-assisted distal gastrectomy with systemic lymphadenectomy for early gastric cancer. World J Gastroenterol 11(47): 7508-7511, 2005

12. Kitano S, Iso Y, Moriyama M, Sugimachi K: Laparoscopy-assisted Billroth I gastrectomy. Surg Laparosc Endosc 4(2): 146-148, 1994

13. Kitano S, Shiraishi N: Current status of laparoscopic gastrectomy for cancer in Japan. Surg Endosc 18: 182-185, 2004

14. Kitano S, Shiraishi N, Fujii K, Yasuda K, Inomata M, Adachi Y: A randomized controlled trial comparing open vs laparoscopy-assisted distal gastrectomy for the treatment of early gastric cancer: an interim report. Surgery 131: 306-311, 2002

15. Kitano S, Shiraishi N, Uyama I, Sugihara K, Tanigawa N, Japanese Laparoscopic Surgery Study Group: A multicenter study on oncologic outcome of laparoscopic gastrectomy for early cancer in japan. Ann Surg 245: 68-72, 2007

16. Mochiki E, Kamiyama Y, Aihara R, Nakabayashi T, Asao T, Kuwano H: Laparoscopic assisted distal gastrectomy for early gastric cancer: Five years’ experience. Surgery 137(3): 317-322, 2005

17. Matin SF, Abreu S, Ramani A, Steinberg AP, Desai M, Strzempkowski B, Yang Y, Shen Y, Gill IS: Evaluation of age and comorbidity as risk factors after laparoscopic urological surgery. J Urol 170: 1115-1120, 2003

18. Noshiro H, Nagai E, Shimizu S, Uchiyama A, Tanaka M: Laparoscopically assisted distal gastrectomy with standard radical lymph node dissection for gastric cancer. Surg Endosc 19: 1592-1596, 2005

19. Reissman P, Cohen S, Weiss EG, Wexner SD: Laparoscopic colorectal surgery: ascending the learning curve. World J Surg 20(3): 277-281, 1996

20. Vaisbuch E, Goldchmit C, Ofer D, Agmon A, Hagay Z: Laparoscopic hysterectomy versus total abdominal hysterectomy: a comparative study. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod

Biol 126: 234-238, 2006

21. Weber KJ, Reyes CD, Gagner M, Divino M: Comparison of laparoscopic and open gastrectomy for malignant disease. Surg Endosc 17: 968-971, 2003

22. Yano H, Monden T, Kinuta M, Nakano Y, Tono T, Matsui S, Iwazawa T, Kanoh T, Katsushima S: The usefulness of laparoscopy-assisted distal gastrectomy in comparison with that of open gastrectomy for early gastric cancer. Gastric Cancer 4: 93-97, 2001

23. Zingmond D, Maggard M, O’Connell J, Liu J, Etzioni D, Ko C: What predicts serious complications in colorectal cancer resection? Am Surg 69: 969-974, 2003

- 국문요약 -

복강경보조

복강경보조

복강경보조

복강경보조 위절제술의

위절제술의 합병증

위절제술의

위절제술의

합병증

합병증

합병증:

:

:

:

누적

누적 300

누적

누적

300

300

300

례의

례의 다변량

례의

례의

다변량

다변량

다변량 분석

분석

분석

분석

아주대학교 대학원의학과 박 종 민 (지도교수: 한 상 욱) 연구목표 : 복강경보조 위절제술의 합병증은 개복하 위절제술의 합병증과 크게 다르지 않다. 그러나, 복강경보조 위절제술의 접근 방법과 기복형성의 과정, 특 수한 전기적 수술 기기들이 합병증 발생을 증가시킬 수 있다. 본 연구는 단일기 관에서 수집된 자료를 바탕으로 수술 후 합병증과 관련된 원인과 위험 인자들을 분석하였다. 재료 및 방법 : 2003년 5월부터 2006년 10월까지 위암으로 복강경보조 위절제 술을 시행받은 300명의 환자들을 후향적으로 분석하였다. 42명이 위전절제술, 258명이 원위부 위절제술, 3명이 근위부 위절제술을 시행하였다. 체질량 지수, 동반질환, 복부수술 기왕력, 수술 시간, 수술 종류, 림프절 절제범위, 절제된 림 프절 수, 전이된 림프절의 수, 동반된 수술, 종양의 침윤도, 병기 등의 임상병리 학적 자료가 수집되어 수술 사망률, 합병증, 술 후 재원기간 등을 분석하였다. 300명의 환자들은 첫 50례까지 1구간, 구 후 250례에 대하여 2구간으로 분류 하였다. 결과 : 술 후 합병증은 61(20.3%)명에서 발생되었다. 상처 감염이 21명(7.0%), 복강내 농양 3(1.0%)명, 출혈 12(4.0%)명, 문합부 협착 13(4.3%)명, 문합부 누출 3(1.0%)명, 급성 췌장염 2(0.7%)명, 폐합병증 4(1.3%)명, 신장 합병증 4(1.3%)명, 심장 합병증 2(0.7%)명이었다. 수술 사망률은 2(0.7%)이었고 단변량 분석에서 성별, 수술 기간, 동반질환, 수술 시간이 의미있는 위험인자로 분석 되었다. 다변량 분석에서는 동반질환과 수술 기간이 중요한 위험인자로 분석되었 다. 결론 : 본 연구는 복강경 보조 위절제술이 용인될 수 있는 수술 합병증을 발생시 키는 것을 증명하는 자료이다. 복강경 보조 위절제술은 술자의 경험과 주의깊은 환자 선택으로 적절한 수술 결과를 얻을 수 있을 것이다. 핵심어 핵심어 핵심어 핵심어 : 복강경보조 위절제술, 위암, 합병증, 학습곡선