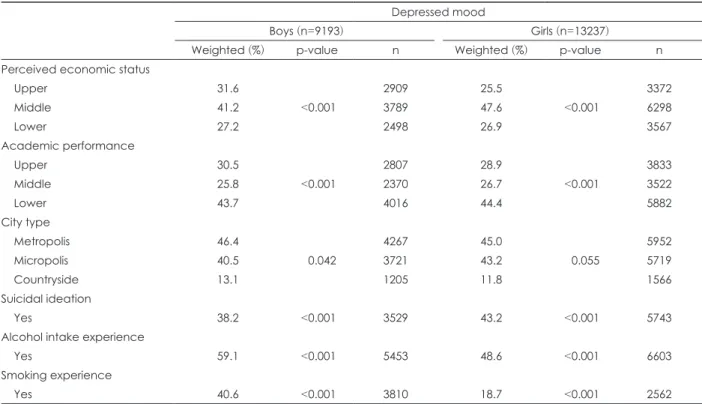

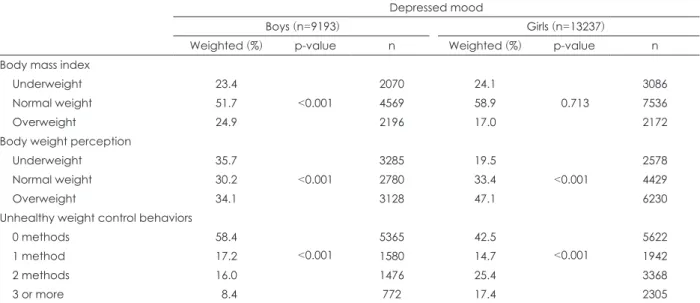

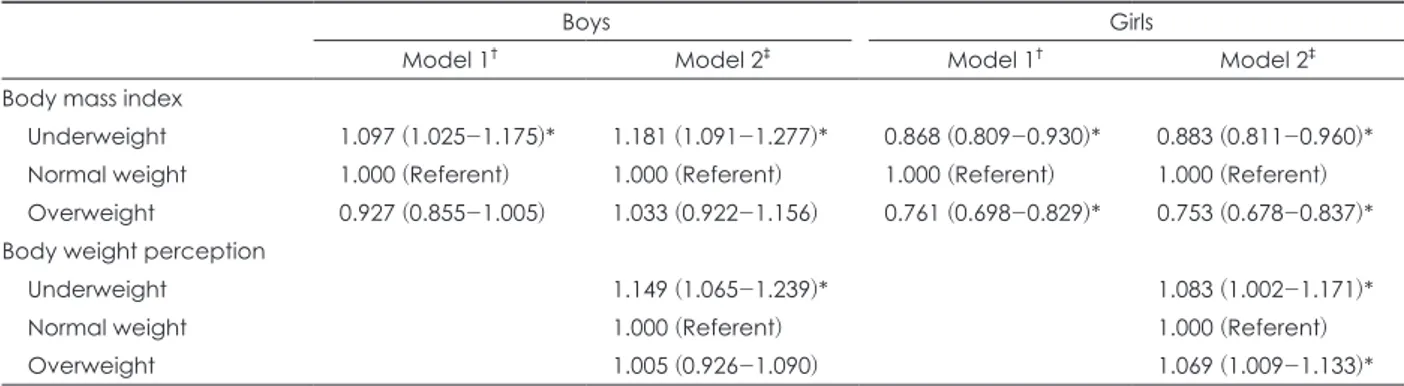

Body Mass Index, Body Weight Perception, and Depressed Mood in Korean Adolescents

전체 글

수치

관련 문서

As a result of a reviewing alternation of school uniforms difference used by body type that the thin body size and standard body size of perception

Our study investigated the preventive effects of resist- ance exercise on body weight, gonadal fat mass, and glucose tolerance and determined whether the ben- eficial

Effects of high-fat diet and various concentrations of CG200745 on blood pressure and body weight in mice... Effects of various concentrations of CG200745 on expression

Third, the analysis of the body-centered vertical speed between male.. and female students showed that male students appeared faster than female students at

Conclusions: This study suggests that psychological health factors such as stress perception, depression and suicidal ideation are related to the quality of sleep

This study aims to identify whether socioeconomic level of parents affects obesity of adolescents and whether the relations between adolescent's obesity

Health behavior of multicultural and general family adolescents in Korea: the Korea Youth Risk.. Behavior

This study aims to analyse the relations between stress and eating habits of adolescents as it was assumed that adolescents need lots of nutrients and eating habits