저작자표시-비영리-변경금지 2.0 대한민국 이용자는 아래의 조건을 따르는 경우에 한하여 자유롭게 l 이 저작물을 복제, 배포, 전송, 전시, 공연 및 방송할 수 있습니다. 다음과 같은 조건을 따라야 합니다: l 귀하는, 이 저작물의 재이용이나 배포의 경우, 이 저작물에 적용된 이용허락조건 을 명확하게 나타내어야 합니다. l 저작권자로부터 별도의 허가를 받으면 이러한 조건들은 적용되지 않습니다. 저작권법에 따른 이용자의 권리는 위의 내용에 의하여 영향을 받지 않습니다. 이것은 이용허락규약(Legal Code)을 이해하기 쉽게 요약한 것입니다. Disclaimer 저작자표시. 귀하는 원저작자를 표시하여야 합니다. 비영리. 귀하는 이 저작물을 영리 목적으로 이용할 수 없습니다. 변경금지. 귀하는 이 저작물을 개작, 변형 또는 가공할 수 없습니다.

Is Surgical Management Necessary for Primary

External Auditory Canal Cholesteatoma?

by

Minhyuk Cho

Major in Medicine

Department of Medical Sciences

The Graduate School, Ajou University

Is Surgical Management Necessary for Primary

External Auditory Canal Cholesteatoma?

by

Minhyuk Cho

A Dissertation Submitted to The Graduate School of

Ajou University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements

for the Degree of

Master of Medicine

Supervised by

Yun-HoonChoung,M.D., D.D.S., Ph.D.

Major in Medicine

Department of Medical Sciences

The Graduate School, Ajou University

This certifies that the dissertation

ofMinhyuk Cho is approved.

SUPERVISORY COMMITTEE

Yun-HoonChoung

Chul-Ho Kim

Hun Yi Park

The Graduate School, Ajou University

December, 21st, 2016

i - ABSTRACT -

Is Surgical Management Necessary for Primary External Auditory

Canal Cholesteatoma?

Objective: To evaluate the effectiveness of nonsurgical management in primary external auditory canal cholesteatoma (EACC). Study Design: Retrospective case review. Setting: Tertiary care university hospital. Patients and Methods: From 2005 to 2015, 23 patients

diagnosed as primary EACC were reviewed with regard to demographics, physical examination, pure tone audiometry, temporal bone CT findings, clinical management and treatment outcome. Results: Total 24 ears (1 bilateral case) were involved in this study. Stage IV lesion was

presented in only one ear (4.2%, mastoid invasion) and this case required surgery. Twenty three ears (95.8%) were managed welljust by serial cleaning without disease progression or symptom aggravation.Among the 5 ears which showed air-bone gap on pure tone audiometry before treatment, 4 cases (80%, including 1 ear treated by surgery) showed no air-bone gap and the other 1 ear showed maintained air-bone gap on follow-up test after treatment. Conclusion: Unless the disease invades adjacent anatomical structures such as mastoid, perhaps primary EACC can be successfully controlled with nonsurgical management.

ii

TABLE OF CONTENTS

ABSTRACT ... i

TABLE OF CONTENTS ... ii

LIST OF FIGURES ...iii

LIST OF TABLES ... iv

I. INTRODUCTION ... 1

II. MATERIALS AND METHODS... 8

III. RESULTS ... 9

A. CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS... 9

B. LOCATION AND STAGE ... 9

C. TREATMENT ... 9

IV. DISCUSSION ... 19

V. CONCLUSION ... 21

REFERENCES ... 22

iii

LIST OF FIGURES

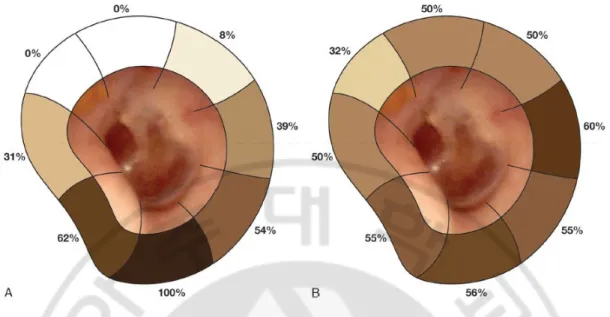

Fig. 1. Proportion of external auditory canal cholesteatoma distribution ... 4

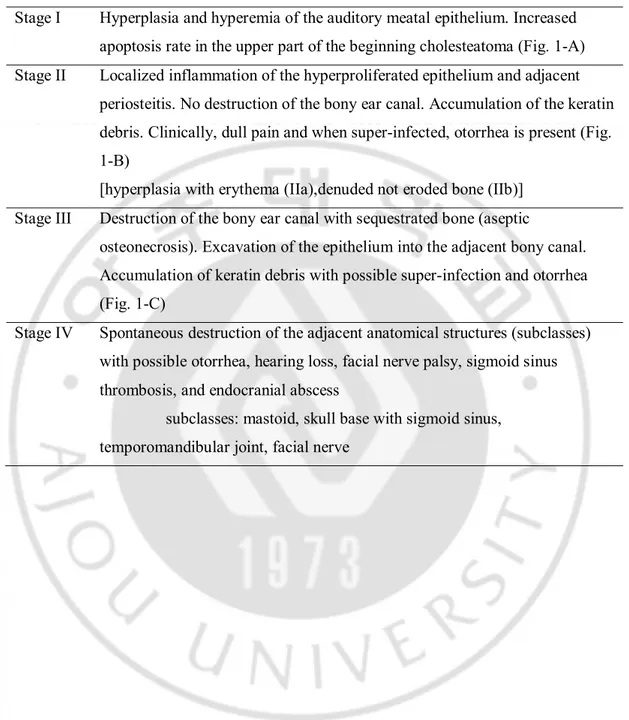

Fig. 2. Stages of external auditory canal cholesteatoma ... 7

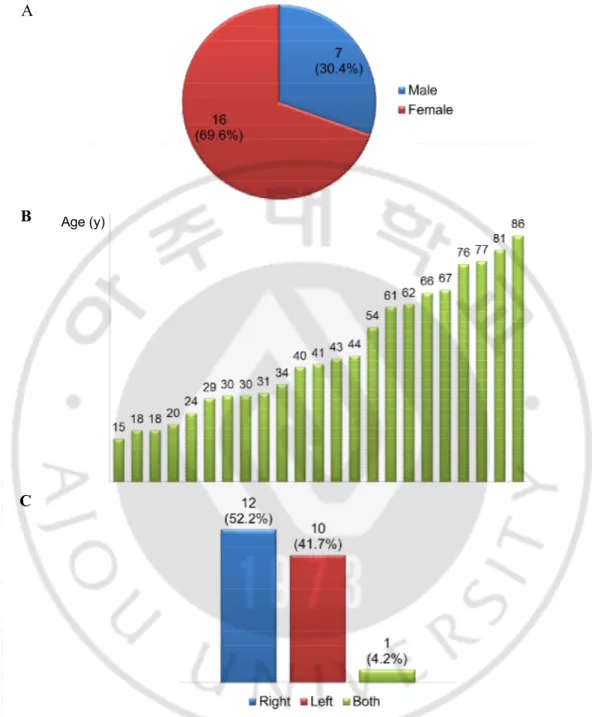

Fig. 3. Sex, age and the affected side of the patients ... 11

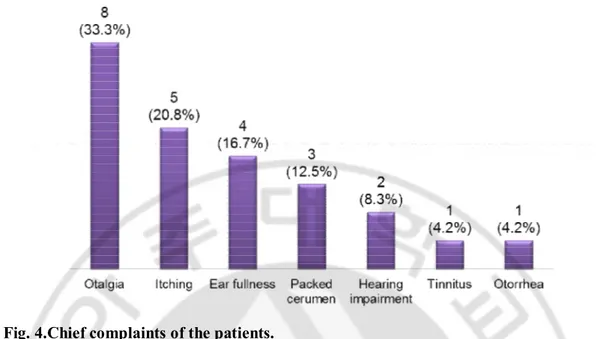

Fig. 4. Chief complaint of the patients ... 12

Fig. 5. Location of external auditory canal cholesteatomaprojected schematically onto a standard left ear ... 13

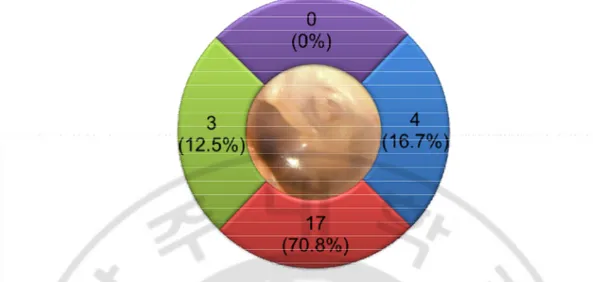

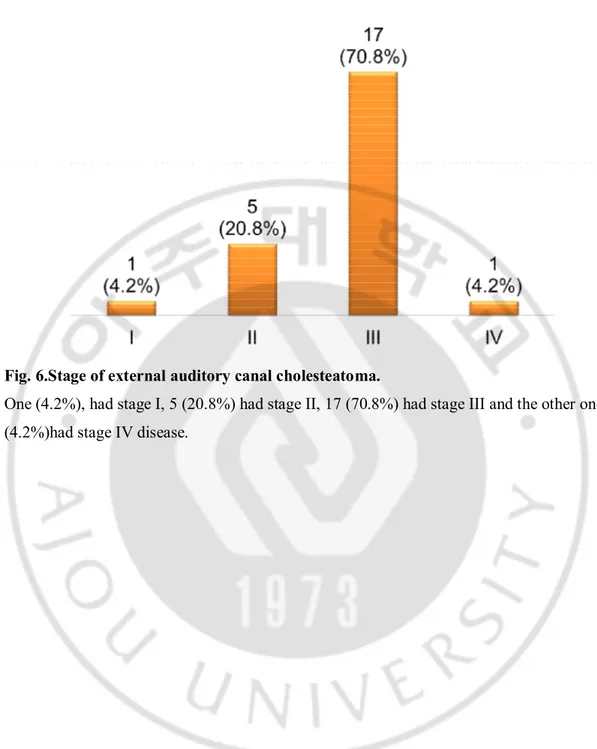

Fig. 6. Stage of external auditory canal cholesteatoma ... 14

Fig. 7. An example case which was successfully managed by serial cleaning only ... 15

Fig. 8. The only case with stage IV disease (mastoid invasion) which required surgical management (Bondy operation) ... 16

Fig. 9. Initial pure tone audiometry results and follow-up test results of the patients who showed air-bone gap on the initial test ... 17

iv

LIST OFTABLES

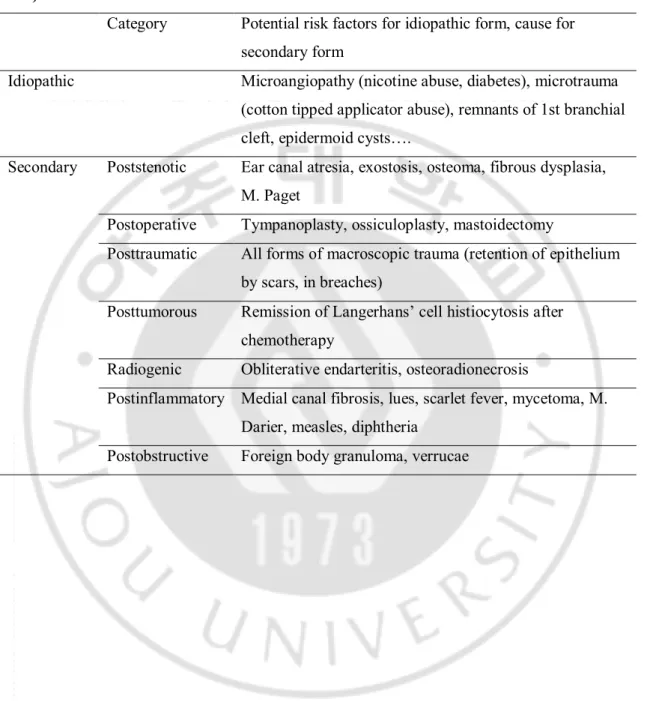

Table 1. Etiologic classification of external auditory canal cholesteatoma ... 3

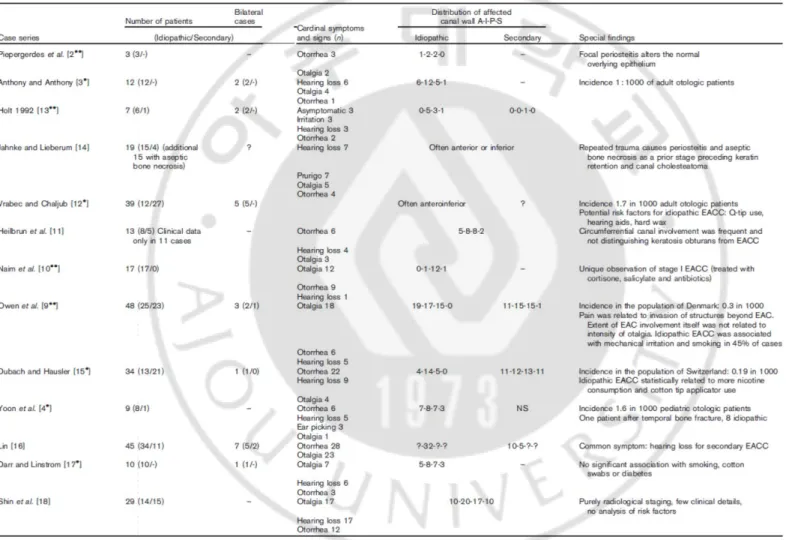

Table 2. Meta-analysis of 13 case series of external auditory canal cholesteatoma ... 5

Table 3. Stages of external auditory canal cholesteatoma ... 6

Table 4. Summary of the clinical information from the primary external auditory canal

1

I. INTRODUCTION

Cholesteatoma are cystic masses lined with stratified keratinizing squamous epithelium and most develop in the middle ear cavity.They rarely originate in the external auditory canal (EAC) with an estimated incidence of 1.2 per 1,000 of all new otologic patients (Anthony and Anthony, 1982). External auditory canal cholesteatoma (EACC) may develop spontaneously (idiopathic) or as a consequence of stenosis, inflammation, obstruction, tumor, trauma, radiation and surgery (Table 1) (Dubach et al., 2010).In the spontaneous (primary) form of EACC, disturbed local circulation of the epidermal layer of the tympanic membrane and the auditory canal was claimed to be the etiologic factor for disturbed epithelial migration in the area of the EAC (Makino and Amatsu 1986). However, thisturned out to be false according to a control study showing thatthere was no significant difference between normaland EACC in

epitheliummigration velocity (Bonding and Ravn, 2008). Thus the debate on the pathogenesis of EACC is still ongoing.

Clinically, patients with EACC present with chronicdull pain and otorrhea, which commonly is purulent (Naim, et al., 2005). The pain is caused by the invasion of the squamous tissue into the adjacent bony canal with periosteitis(Naim, et al., 2005). The patients usually do not complain of hearing loss but in some cases, they present with conductive hearing loss that is caused by occlusion of the external canal by the debris or the cholesteatoma (Naim, 2004). Some patients are asymptomatic, especially in early staged diseases. In a meta-analysis done by Dubach, et al., the presented cardinal symptoms of EACC patients were unilateral otorrhea in most of the studies (5 of 13) and unilateral otalgia (4 of 12) or itching was also reported.

According to a case series of 34 patients with EACC reported by Dubach, et al.,

secondary EACC had random and even multifocal location,whereasidiopathic (primary) EACC cases were typically located at the floor ofthe auditory canal in majority of the studies (12 out of 12 patients and 8 out of 13 studies, respectively) (Fig. 1, Table 2) (Dubach and Häusler, 2008, Dubach, et al., 2010).The differential diagnosis of EACC includes medial canal fibrosis, malignant otitis externa, squamous cell carcinoma and which is most difficult to distinguish from EACC, keratosis obturans (Dang and Palacios, 2005). Keratosis obturans is the accumulationof large plugs of desquamated keratin in the ear canal, whereas EACC is characterized as the invasion of squamous tissue into localized areas of bony erosion of the

2 external auditory canal(Piepergerdes,et al., 1980).

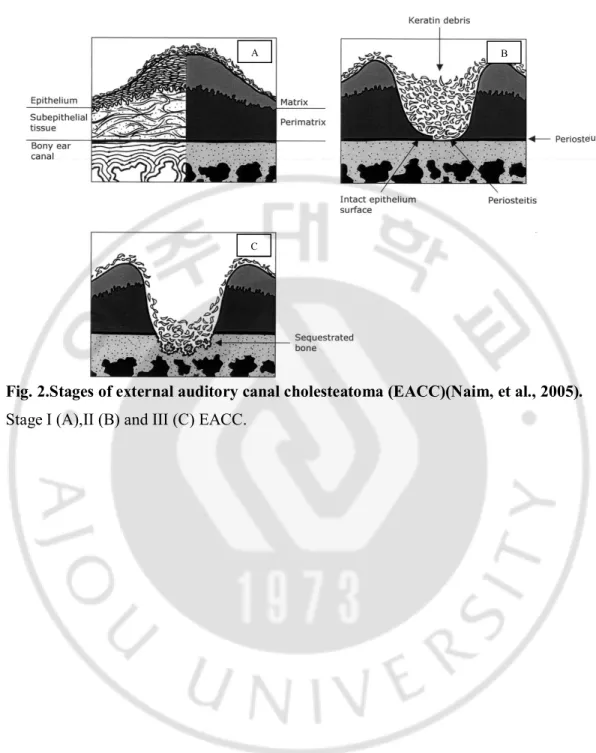

EACC occasionallyextend into the middle ear cavity, mastoid,sigmoid sinus, facial nerve, temporomandibular joint and skull base. Naim,et al.classified this disease into four stages: stage I with hyperplasia of the canal epithelium, stage II including periosteitis, stage III including a defective bony canal, and stage IV showing an destruction of adjacent anatomic structure such as mastoid, skull base, sigmoid sinus, temporomandibular joint and facial nerve (Table 3, Fig. 2) (Naim,et al., 2005).

Treatment of primary EACC is controversial. Dubach and Häusler aimed to effect a curative operation in their EACC patients and considered conservative cleaning at short intervals as a second option (Dubach and Häusler, 2008). Lin reported that to prevent further occult invasion in primary EACCs, surgery is required so that the cholesteatoma and eroded bone can be excised (Lin, 2009). On the other hand, Darr and Linstrom reported that in patients with primary EACC, good control of disease can be achieved through careful, regular, in-office debridement, even in advanced cases (Darr and Linstrom, 2010). Chang,et al. introduced self-cleansing of EAC with acetic acid (dilute vinegar solution) which was effective managing primary EACC without middle ear or mastoid involvement (Chang,et al., 2012). Thus, additional research on the optimal management of EACC is required.In this present study, we performed a retrospective medical record reviewto evaluate the effectiveness of nonsurgical management in primary EACC and to determine the optimal management.

3

Table 1.Etiologic classification of external auditory canal cholesteatoma (Dubach, et al., 2010).

Category Potential risk factors for idiopathic form, cause for secondary form

Idiopathic Microangiopathy (nicotine abuse, diabetes), microtrauma (cotton tipped applicator abuse), remnants of 1st branchial cleft, epidermoid cysts….

Secondary Poststenotic Ear canal atresia, exostosis, osteoma, fibrous dysplasia, M. Paget

Postoperative Tympanoplasty, ossiculoplasty, mastoidectomy

Posttraumatic All forms of macroscopic trauma (retention of epithelium by scars, in breaches)

Posttumorous Remission of Langerhans’ cell histiocytosis after chemotherapy

Radiogenic Obliterative endarteritis, osteoradionecrosis

Postinflammatory Medial canal fibrosis, lues, scarlet fever, mycetoma, M. Darier, measles, diphtheria

4

Fig. 1.Proportion of external auditory canal cholesteatoma (EACC)distribution(Dubach and Häusler, 2008).

(A) Idiopathic (primary) EACC with the predominance of inferior wall involvement. (B) Secondary EACC with ubiquitous distribution.

5

6

Table 3.Stages of external auditory canal cholesteatoma (Naim, et al., 2005).

Stage I Hyperplasia and hyperemia of the auditory meatal epithelium. Increased apoptosis rate in the upper part of the beginning cholesteatoma (Fig. 1-A) Stage II Localized inflammation of the hyperproliferated epithelium and adjacent

periosteitis. No destruction of the bony ear canal. Accumulation of the keratin debris. Clinically, dull pain and when super-infected, otorrhea is present (Fig. 1-B)

[hyperplasia with erythema (IIa),denuded not eroded bone (IIb)] Stage III Destruction of the bony ear canal with sequestrated bone (aseptic

osteonecrosis). Excavation of the epithelium into the adjacent bony canal. Accumulation of keratin debris with possible super-infection and otorrhea (Fig. 1-C)

Stage IV Spontaneous destruction of the adjacent anatomical structures (subclasses) with possible otorrhea, hearing loss, facial nerve palsy, sigmoid sinus thrombosis, and endocranial abscess

subclasses: mastoid, skull base with sigmoid sinus, temporomandibular joint, facial nerve

7

Fig. 2.Stages of external auditory canal cholesteatoma (EACC)(Naim, et al., 2005).

Stage I (A),II (B) and III (C) EACC.

A B

8

II. MATERIALS AND METHODS

The clinical records of 23consecutive patients diagnosed withprimary EACC by a single doctor from the Department of Otolaryngology of a tertiary referral center(Ajou University Hospital, Korea) between May 2005 and June 2015 were collected and

retrospectively reviewed. In each patient, the data were reviewed in respect to sex, age, side of the disease and chief complaint. For diagnosis of EACC, endoscopy, microscopy and temporal bone computed tomography (TBCT)were done in all patients. Biopsy was performed if histopathologic examination was necessary for diagnosis.

Among the patients diagnosed as EACC, those with history of stenosis, trauma, surgery or tumor and other otologic or systemic disease that could affect developing EACC were excluded to select primary EACC cases only. EAC was divided into 4

quadrants(anterior, posterior, superior and inferior) to define the location of the lesion. The stage of the disease was determined according to the stages suggested by Naim,et al.(Naim,et al., 2005).

Pure tone audiometry was taken initially and after treatment. The average of the thresholds was calculated as (0.5kHz + (1kHz × 2) + 2kHz) ÷ 4 for air conduction and bone conductionrespectively to check if there was air-bone gap. Air-bone gap more than 10dB was considered to be significant.

For treatment, serial cleaning was the only thing that was done if the disease could be controlled. If there was anykeratin debris, it was removed meticulously, as completely as possible, by transcanal approach under microscopy at the office. Depending on the condition of EAC, topical antibiotic (ciprofloxacin) and steroid (fluocinolone)eardrop was used if there was any sign of infection, such as otorrhea, and the patient was told to irrigate the affected ear with acetic acid solution diluted with normal saline (2% of concentration, 36-37℃, toward the posterior wall of ear canal, 40ml a time, 4 times a day) at home until the EAC became completely dry under otoscopic examination. The interval between each visit was from a week to months, depending on the condition of the EAC.The treatmentoutcome was evaluated regarding symptoms, endoscopy and microscopy findings, CT findings, pure tone audiometry results, recurrence and complications.

9

III. RESULTS

A. CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS

There were 7 male (30.4%) and 16 female patients (69.6%) and the mean age of the 23 patients was 45.5 ± 21.9 years (15–86 years range). The disease was present on the right in 12 patients (52.2%), on the left in 10 (41.7%) and 1 (4.2%) had bilateral disease (24 ears in total)(Fig. 3).The most common chief complaint was otalgia (8 ears, 33.3%), followed by itching (5 ears, 20.8%), ear fullness (4 ears, 16.7%), packed cerumen (3ears, 12.5%), hearing impairment (2 ears, 8.3%), tinnitus and otorrhea (1 ear, 4.2%, respectively) (Fig. 4).

B. LOCATION AND STAGE

In most of the cases, the disease mainly involved inferior wall of EAC (17 ears,

70.8%). Next came posterior and anterior wall (4 ears, 16.7% and 3 ears, 12.5%, respectively) and superior wall was not the main location of the disease in all cases (Fig. 5). One (4.2%), had stage I, 5 (20.8%) had stage II, 17 (70.8%) had stage III and the other one (4.2%)had stage IV disease (Fig. 6).

C. TREATMENT

For management, serial cleaning wassufficient for disease control in 23 of 24 ears (95.8%)(Fig. 7). They did not need any additional surgical treatment such as canaloplasty, tympanoplasty or mastoidectomy. Among these 23, 9 (39.1%) were treated with acetic acid irrigation without otic solution, 5 (21.7%) were managed with otic solution without acetic acid irrigation, and the other 9 (39.1%) had both. Only 1 ear (4.2%) with mastoid invasion required surgery which was successful (Fig. 8). There was no complication observed such as tympanic membrane perforation and recurrent disease was not developed in all cases.On initial pure tone audiometry, 5 ears (20.8%) including the case with mastoid invasion presented conductive hearing loss and the other 19 ears (79.2%) showed no air-bone gap. In 4 of 5 cases (80%) which showed conductive hearing loss on the initial hearing test,

including the operated ear with mastoid invasion, the follow-up pure tone audiometry taken after management showed no air-bone gap. An 86-year-old female with initial air-bone gap

10

of 40dB was the only patient who showed remaining air-bone gap on follow-up test. Her hearing did not get better, but did not get worse either (Fig. 9).The average follow-up period of the patients was 19.4 ± 19.2 months (range 1–74 months). Table 4 shows the summary of the clinical information from the patients involved in this study.

11

Fig. 3.Sex, age and the affected side of the patients.

(A) There were 7 male (30.4%) and 16 female patients (69.6%). (B) The mean age of the 23 patients was 45.5 ± 21.9 years (15–86 years range). (C) The disease was present on the right in 12 patients (52.2%), on the left in 10 (41.7%) and 1 (4.2%) had bilateral disease.

Age (y) A

B

12

Fig. 4.Chief complaints of the patients.

The most common chief complaint was otalgia (8 ears, 33.3%), followed by itching (5 ears, 20.8%), ear fullness (4 ears, 16.7%), packed cerumen (3ears, 12.5%), hearing impairment (2 ears, 8.3%), tinnitus and otorrhea (1 ear, 4.2%, respectively).

13

Fig. 5. Location of external auditory canal cholesteatomaprojected schematically onto a standard left ear.

In most of the cases, the disease mainly involved inferior wall of external auditory canal (17 ears, 70.8%). Next came posterior and anterior wall (4 ears, 16.7% and 3 ears, 12.5%, respectively) and superior wall was not the main location of the disease in all cases.

14

Fig. 6.Stage of external auditory canal cholesteatoma.

One (4.2%), had stage I, 5 (20.8%) had stage II, 17 (70.8%) had stage III and the other one (4.2%)had stage IV disease.

15

Fig. 7.An example case which was successfully managed by serial cleaning only.

(A) Otoscopy findings from the initial visit showing keratin debris at the inferior wall of the EAC and(B) bony erosion after keratin debris removal. (C) Otoscopy finding after serial cleaning with acetic acid (52 months later from the first visit) presenting clear canal without disease progression.

16

Fig. 8.The only case with stage IV disease (mastoid invasion) which required surgical management (Bondy operation).

Endoscopic finding showing keratin debris and bone destruction (A) and temporal bone computed tomography findings presenting the lesion invading mastoid (B). The air-bone gap (30dB) shown on the initial pure tone audiometry disappeared after surgery (C).

A B

17

Fig. 9.Initial pure tone audiometryresults and follow-up test results of the patients who showed air-bone gap on the initial test.

(A) On initial pure tone audiometry, 5 ears (20.8%) including the case with mastoid invasion presented conductive hearing loss and the other 19 ears (79.2%) showed no air-bone (AB) gap. (B) In 4 of 5 cases (80%) which showed conductive hearing loss on the initial hearing test, including the operated ear with mastoid invasion, the follow-up pure tone audiometry taken after management showed no AB gap. An 86-year-old female with initialAB gap of 40dB was the only patient who showed remaining AB gap on follow-up test. Her hearing did not get better, but did not get worse either.

B A

18

Table 4.Summary of the clinical information from the primary external auditory canal cholesteatoma patients involved in this study.

a:same patient (with bilateral disease)

Case # Age Sex Side Location Stage Treatment Air-bone gap (dB) Follow-up period (month) Initial Follow-up 1 62 M R P III Conservative No No 1 2 76 F L I I Conservative No No 36 3 43 F L I I Conservative 35 No 2 4 31 F R I III Conservative No No 52 5 77 F R P II Conservative No No 1 6a 41 F R I II Conservative No No 30 7a L I II Conservative 25 No 30 8 54 F R I I Conservative No No 10 9 18 F R I II Conservative No No 1 10 61 M R P IV Operation 30 No 5 11 86 F L I II Conservative 40 40 26 12 29 M L I II Conservative No No 16 13 40 F R A II Conservative No No 34 14 15 F L A III Conservative No No 7 15 67 F L I III Conservative No No 25 16 18 M R A II Conservative No No 1 17 30 M R P III Conservative No No 1 18 44 M L I III Conservative No No 1 19 66 F R I III Conservative No No 25 20 81 F L I II Conservative No No 28 21 34 F L I II Conservative No No 74 22 30 M R I II Conservative No No 21 23 24 F L I III Conservative 35 No 23 24 20 F R I III Conservative No No 2

19

IV. DISCUSSION

Primary EACC is rare disease and its pathogenesis and optimal management remains unclear. Chronic use of cotton tipped applicators has been described as a potential risk factor (Jahnke and Lieberum, 1995, Quantin, et al., 2002), but whether it is a cause or just

accompanied by otorrheais uncertain.In a case series of 12 spontaneous EACC, hard cerumen, Q-tipinjury, and pressure from a hearing aid were the most common causes (Vrabec and Chaljub, 2010). Culturally, frequent use of ear picks with cotton or metal tip is common in our country (Korea) and this may led EACC to occur in some patients though we could not get exact history of the patients due to the limitation of retrospective study.

The male-to-female ratio was 7:16 in this study. In several previous studies, the ratios were 22:12 (Dubach, et al., 2008, Switzerland), 7:12 (Chang, et al., 2012, Korea), 12:16 (Konishi, et al., 2016, Japan) and 6:9 (Sakalli, et al., 2016, Turkey). There may be slight female predominance, particularly in Asian population, but because the numbers of subjects involved in these studies were small, more data should be collected to decide if this is true.

The most common chief complaint in this study turned out to be otalgia (8 ears, 33.3%) and not like the previous studies(Dubach et al., 2010),otorrhea was uncommon chief

complaint (1 ear, 4.2%). The differential diagnosis of EACC includes diseases such as malignant otitis media and squamous cell carcinoma, which can be presented with common symptoms with EACC. Thus, careful history taking and thorough examination should be done and in some uncertain cases, histopathologic examination through biopsy should also be considered to prevent misdiagnosis and enable early treatment for those life-threatening diseases.

In previous studies, the inferior wall of EAC is especially frequently involved in primary EACC (Dubach et al., 2010). The inferior wall ofthe pars tympanicahas less vascularization comparing with the superior wall which containsvascular strip and because of this, the floor of the canal may be the most susceptible site for recurrent microtrauma ormicroangiopathy owing to smoking or diabetes (Dubach, et al., 2010). In this study also, the inferior wall was the most commonly involved site among the 4 quadrants of EAC (17 ears, 70.8%) and there was no case involving the superior wall.

20

be because early staged diseases do not cause symptom and only advanced cases whichcould not be managed at local clinics were referred to our tertiary center. Darr and Linstrom reported that good control of disease can be achieved through careful, regular, in-office debridement, even in advanced primary EACC cases (Darrand Linstrom, 2010). By a meta-analysis of 13 major case series of EACC published by 2010, the authors concluded that as far as therapy is concerned, surgical treatment of EACC is the method of choice for EACC in advanced stage (Naim stage IIb and more). (Dubach, et al., 2010) In a recent case review, Konishi, et al. treated 10 stage III and 18 stageIV (Naim stage) EACC patients with surgical intervention (Konishi, et al., 2016).In our study, among the 24 ears involved, 23 ears (95.8%) presented stage I-III disease (17 were stage III) and they were all successfullyand safely managed just by serial cleaning with topical ear drops (consisted of antibiotic and steroid)and acetic acid.There was only 1 case (4.2%) with stage IV lesion which required surgery. AfterBondy operation, the treatment result was also successful in this patient. Neither complication, including perforation of the tympanic membrane, nor recurrence developed in all patients, including the only case managed though surgical intervention.

Losing acidity can interrupt the recovery of EAC from infection or inflammation. Thus, acetic acid irrigation can assist the diseased EAC to restore by regaining normal acidity of EAC.Serial cleaning is a noninvasive, low-cost treatment which assists natural healing of the diseased mucosa. By this method, most of the primary EACCs can be managed without complications, unless there is invasion to the mastoid or other farther structures, butit requires long follow-up period. In cases of recurrence, conservative

treatment with serial cleaning can be tried again but if the recurrence is frequent or for highly advanced lesion (stage IV) surgical intervention should be considered. This study was executed retrospectively, not prospectively. The number of the subjects involved was 23 and there was no control group. Also, the mean follow-up period o was 19.4 ± 19.2 months (range 1–74 months) and it is unclear if recurrence may occur after longer period. Therefore, additional data from further prospectively designed, controlled studies with large-scale for long-term are required to verify our results.

21

V. CONCLUSION

Primary EACC is an uncommon disease and there is no consensus on optimal management of this disease. In this study, just cleaning the EAC serially was sufficient to prevent disease progression and preserve hearing for all primary EACC cases except only one case with stage IV lesion invading mastoid. Primary EACC can be successfully controlled by conservative treatment only without surgical management, unless the lesion invades adjacent anatomical structures such as mastoid. Further studies are needed to understand the pathogenesis and to decide the optimal treatment of this uncommon disease.

22

REFERENCES

1. Anthony PF, Anthony WP: Surgical treatment of external auditory canal cholesteatoma.

Laryngoscope92(1): 70-5, 1982

2. Bonding P, Ravn T: Primarycholesteatoma of the external auditory canal: is the epithelialmigrationdefective?.OtolNeurotol 29(3): 334-338, 2008

3. Chang J, Choi J, Im GJ, Jung HH: Dilute vinegar therapy for the management of

spontaneous external auditory canal cholesteatoma.Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 269(2): 481-485, 2012

4. Dang M, Palacios E:External auditory canalcholesteatoma: a rareentity.Ear Nose

ThroatJ85(12): 806, 808, 2006

5. Darr EA, Linstrom CJ:Conservative management of advanced external auditory canal cholesteatoma. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 142(2): 278-280, 2010

6. Dubach P, Mantokoudis G, Caversaccio M: Ear canal cholesteatoma: meta-analysis of clinical characteristics with update on classification, staging and treatment.

CurrOpinOtolaryngol Head Neck Surg18(5): 369-376, 2010

7. Dubach P,Häusler R. External Auditory Canal Cholesteatoma: Reassessment of and Amendments to Its Categorization, Pathogenesis, and Treatment in 34 Patients.

Otol&Neurotol29(7): 941-948, 2008

8. Jahnke K,Lieberum B: Surgery of cholesteatoma of the ear canal.Laryngorhinootologie 74(1): 46-49, 1995

9. Konishi M, Iwai H, Tomoda K: Reexamination of Etiology and SurgicalOutcome in Patientwith AdvancedExternalAuditoryCanalCholesteatoma. OtolNeurotol 37(6): 728-734, 2016

10. Lin YS:Surgicalresults of externalcanalcholesteatoma.ActaOtolaryngol 129(6): 615-623, 2009

11. Makino K,Amatsu M: Epithelial migration on the tympanic membrane and external canal.

Arch Otorhinolaryngol243(1):39-42, 1986

12. Naim R, Linthicum F Jr:External auditory canal cholesteatoma. OtolNeurotol25(3): 412-413, 2004

23

auditory canal cholesteatoma. Laryngoscope 115(3): 455-460, 2005

14. Piepergerdes MC, Kramer BM, Behnke EE: Keratosis obturansand external auditory canal cholesteatoma. Laryngoscope 90(3): 383-391, 1980

15. Quantin L, Carrera Fernández S, Moretti J: Congenital cholesteatoma of external auditory canal. Int J PediatrOtorhinolaryngol62(2): 175-179, 2002

16. Sakalli E1, Kaya D, Celikyurt C, Erdurak SC: Clinicalcharacteristics and follow-up of

patients with externalearcanalcholesteatomatreatedconservatively. Ear Nose Throat J 95(7): 269-273, 2016

24 - 국문요약 –