ORIGINAL ARTICLE

연령군에 따른 Clostridium difficile 감염 입원환자의 임상경과

이호찬, 김경옥, 정요한, 이시형, 장병익, 김태년

영남대학교 의과대학 내과학교실 소화기내과

Clinical Outcomes in Hospitalized Patients with Clostridium difficile Infection by Age Group

Ho Chan Lee, Kyeong Ok Kim, Yo Han Jeong, Si Hyung Lee, Byung Ik Jang, and Tae Nyeun Kim

Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Department of Internal Medicine, Yeungnam University College of Medicine, Daegu, Korea

Background/Aims: Advanced age is a known risk factor of poor outcomes for colitis, including Clostridium difficile infection (CDI). The present study compares the clinical outcomes of young and old patients hospitalized for CDI.

Methods: The clinical records of patients admitted from January 2007 to December 2013 with a diagnosis of CDI were analyzed.

Patient baseline characteristics, clinical courses, and outcomes were compared with respect to age using a cut-off 65 years.

Results: Of the 241,391 inpatients registered during the study period, 225 (0.1%) with a diagnosis of CDI were included in the study. The mean patient age was 67.7 years. Seventy-two patients (32.0%) were younger than 65 years and 153 patients (68.0%) were 65 years old or more. The male to female ratio in the younger group was 0.8, and 0.58 in the older group.

All 225 study subjects had watery diarrhea; six patients (8.3%) complained of bloody diarrhea in the young group and 21 patients (13.7%) in the old group (p=0.246). Right colon involvement was more common in the old group (23.5% vs. 42.7%, p=0.033). Furthermore, leukocytosis (41.7% vs. 67.3%, p=0.000), a CDI score of ≥3 points (77.8% vs. 89.5%, p=0.018), and hypoalbuminemia (58.3% vs. 76.5%, p=0.005) were more common in the old group. Failure to first line treatment was more common in the old group (17 [23.6%] vs. 58 [37.9%], p=0.034).

Conclusions: Severe colitis and failure to first line treatment were significantly more common in patients age 65 years or more. More aggressive initial treatment should be considered for older CDI patients. (Korean J Gastroenterol 2016;67:81-86) Key Words: Clostridium difficile infection; Elderly; Severity; Treatment

Received November 13, 2015. Revised January 7, 2016. Accepted January 8, 2016.

CC This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/

by-nc/4.0) which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Copyright © 2016. Korean Society of Gastroenterology.

교신저자: 김경옥, 42415, 대구시 남구 현충로 170, 영남대학교 의과대학 내과학교실 소화기내과

Correspondence to: Kyeong Ok Kim, Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Department of Internal Medicine, Yeungnam University College of Medicine, 170 Hyeonchung-ro, Namgu, Daegu 42415, Korea. Tel: +82-53-620-3835, Fax: +82-53-623-8038, E-mail: kokim@yu.ac.kr

Financial support: None. Conflict of interest: None.

INTRODUCTION

The rise in incidence and severity of Clostridium difficile in- fection (CDI) is of concern.1-5 According to a study conducted in the United States, from 1997 to 2007 the prevalence and mortality, case-fatality, and colectomy rates of patients with CDI increased markedly.6 These increases are attributed to increases in older patients with underlying diseases and the use of antibiotics, including newly developed cephalosporin and quinolone.6,7 In addition, the emergence of the highly

toxigenic strain, BI/NAP1, has resulted in CDI becoming a cause of increased health care costs and mortality, espe- cially in older patients.2,3,8 In BI/NAP1 outbreaks, age over 65 years was an important risk factor of CDI, of higher mortality and greater disease severity.1,9,10 CDI in older patients was identified as a major contributor to the increased cost of healthcare.11-14

Although advanced age has been identified as a risk factor of CDI, few comparative studies have been conducted on the clinical outcomes of CDI in young and old patients.

Accordingly, the aims of the present study were to evaluate and compare clinical features, severities of symptoms, treat- ment, and clinical outcomes of young vs. old (less than 65 years vs. 65 years and up) CDI hospitalized patients.

SUBJECTS AND METHODS

The medical records of hospitalized patients with a diag- nosis of CDI treated from January 2007 to December 2013 were reviewed. We included only patients who were diag- nosed more than 72 hours after admission. Individuals with a history of inflammatory bowel disease, toxic megacolon, ex- posure to vancomycin or metronidazole, or more than one oc- currence of CDI within a period of three months prior to ad- mission were excluded.

Patient baseline characteristics, clinical features of CDI, including symptoms, disease severity, laboratory findings, treatment, and outcomes were assessed. To compare clin- ical outcomes in the young and old study groups, patients were divided into two groups using a cutoff of 65 years.

CDI was diagnosed based on the presence of symptoms (usually diarrhea), and either a stool test result positive for C.

difficile toxins or toxigenic C. difficile, or colonoscopic find- ings typical of pseudomembranous colitis.7

Disease severity was classified as follows: mild disease (severity 1), CDI with only diarrhea; moderate disease (severity 2), CDI with diarrhea but without additional symp- toms and signs meeting the definition of severe or compli- cated CDI detailed below; severe disease (severity 3), CDI presenting with or developing hypoalbuminemia (serum al- bumin <3 g/dL) and either of the following: (a) a white blood cell (WBC) count of ≥15,000 cells/mm3, or (b) abdominal tenderness without the criteria of complicated disease.

Complicated CDI (severity 4) is defined as CDI presenting with or developing at least one of the following signs or symptoms:

admission to an intensive care unit, hypotension with or with- out the required use of vasopressors, fever (≥38.5oC), ileus, or significant abdominal distention, mental status changes, WBC ≥35,000 cells/mm3 or <2,000 cells/mm3, serum lac- tate levels >2.2 mmol/L, or any evidence of organ failure.

Symptoms of ileus include acute nausea, emesis, sudden cessation of diarrhea, abdominal distention, or radiological signs consistent with disturbed intestinal transit.15

Treatment failure was defined as the absence of clinical

improvement after five days of treatment or the need to change treatment regimen because of poor clinical response.

Recurrence was defined as any recurrence of CDI within 90 days after initial presentation.

All deaths that occurred after diagnosis of CDI were re- viewed by medical chart. We determined whether the death was (1) directly related to CDI (the patient had no other under- lying condition that would have caused death during admis- sion); (2) indirectly related to CDI (the CDI contributed to the patient’s death but was not the primary cause). We included only mortality directly related to CDI.

Statistical analysis was performed using PASW Statistics ver. 18.0 software for Windows (IBM Co., Armonk, NY, USA).

Values are presented as means±SDs. The independent t-test was used to compare continuous variables and the chi-square test to compare categorical variables. Binary logistic re- gression analysis was used to identify risks for first line treat- ment failure. Null hypotheses of no difference were rejected if p-values were less than 0.05 or equivalently, if the 95% CIs of risk point estimates excluded 1.

RESULTS

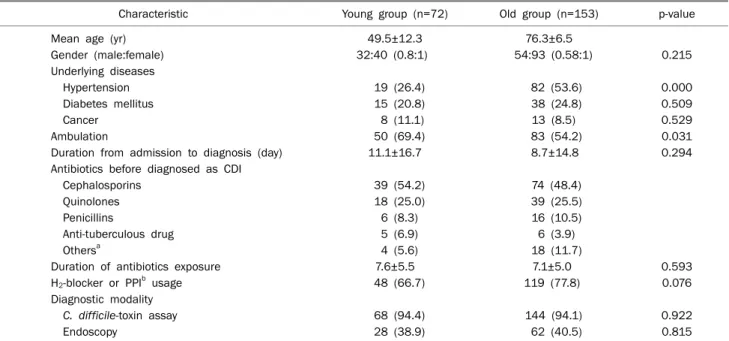

Of the 241,391 patients hospitalized during the study peri- od, 225 (0.1%) received a diagnosis of CDI. The mean patient age was 67.7±15.3 years, 72 (32.0%) were younger than 65 years (the young group) and 153 (68.0%) were 65 years or more (the old group). The mean ages in the young and old groups were 49.5 and 76.3 years, respectively, correspond- ing male/female ratios were 1:0.8 and 1:0.58, and the mean times between admission and diagnosis of CDI were 11.1 and 8.7 days, respectively. Regarding the admission depart- ments involved, 143 patients (63.6%) were admitted to in- ternal medicine, 18 (8.0%) to neuromedicine, 16 (7.1%) to general surgery, 13 (5.8%) to orthopedic surgery, and 13 (5.8%) to neurosurgery. Patients with hypertension were more common in the old group (26.4% vs. 53.6%; p<0.05).

However, malignancy and diabetes mellitus rates were not significantly different in the two groups.

The mean durations of antibiotic exposures (7.6±5.5 and 7.1±5.0 days, respectively; p=0.593), H2-blocker (66.7%), and proton pump inhibitor use (77.8%) before diagnosis did not differ significantly between the young and old groups.

Types of antibiotic used before diagnosis included cepha-

Table 1. Patient Baseline Characteristics

Characteristic Young group (n=72) Old group (n=153) p-value

Mean age (yr) 49.5±12.3 76.3±6.5

Gender (male:female) 32:40 (0.8:1) 54:93 (0.58:1) 0.215

Underlying diseases

Hypertension 19 (26.4) 82 (53.6) 0.000

Diabetes mellitus 15 (20.8) 38 (24.8) 0.509

Cancer 8 (11.1) 13 (8.5) 0.529

Ambulation 50 (69.4) 83 (54.2) 0.031

Duration from admission to diagnosis (day) 11.1±16.7 8.7±14.8 0.294

Antibiotics before diagnosed as CDI

Cephalosporins 39 (54.2) 74 (48.4)

Quinolones 18 (25.0) 39 (25.5)

Penicillins 6 (8.3) 16 (10.5)

Anti-tuberculous drug 5 (6.9) 6 (3.9)

Othersa 4 (5.6) 18 (11.7)

Duration of antibiotics exposure 7.6±5.5 7.1±5.0 0.593

H2-blocker or PPIb usage 48 (66.7) 119 (77.8) 0.076

Diagnostic modality

C. difficile-toxin assay 68 (94.4) 144 (94.1) 0.922

Endoscopy 28 (38.9) 62 (40.5) 0.815

Values are presented as mean±SD, n only, or n (%).

Young group, less than 65 years; old group, 65 years and up.

CDI, Clostridium difficile infection; PPI: proton pump inhibitor.

aCarbapenem, aminoglycosides; bwithin 30 days before presentation.

Table 2. Clinical Characteristics of the Two Study Groups

Characteristic Young group (n=72)

Old group (n=153) p-value Right colon involvement 8/34 (23.5) 35/82 (42.7) 0.033 Symptoms

Watery diarrhea 72 (100) 153 (100) Blood in stool 6 (8.3) 21 (13.7) 0.246 Abdominal pain 26 (36.1) 63 (41.2) 0.469

Fever 54 (75.0) 124 (81.0) 0.298

Hypotension 22 (30.6) 45 (29.4) 0.861

Leukocytosis 30 (41.7) 103 (67.3) 0.000

Hypokalemia 23 (32.4) 48 (31.4) 0.878

Kidney failure 18 (25.0) 40 (26.1) 0.855 Hypoalbuminemia 42 (58.3) 117 (76.5) 0.005 Severity

1 4 (5.6) 3 (2.0)

2 12 (16.7) 13 (8.5)

3 54 (75.0) 134 (87.6)

4 2 (2.8) 3 (2.0)

Values are presented as n (%).

Young group, less than 65 years; old group, 65 years and up.

losporins (54.2% vs. 48.4%), quinolone (25.0% vs. 25.5%), and penicillin (8.3% vs. 10.5%) in young vs. old group. Anti- tuberculosis drugs caused CDI in five members of the young group (5/72, 6.9%) and in six members of the old group (6/153, 3.9%).

A greater percentage of young patients were able to ambu- late (69.4% vs. 54.2%, p<0.05). Modalities used for diag- nosing CDI were the C. difficile toxin assay and endoscopy.

The diagnostic modalities used in the two groups were similar. Typical endoscopic findings were obtained in 67.9%

of the young group and in 70.9% of the old group (Table 1).

The right colon involvement was more common in the old group (8/34 [23.5%] vs. 35/82, [42.7%], p=0.033). All 225 study subjects complained of watery diarrhea. Fifty-four (75.0%) patients had fever in the young group and 124 (81.0%) in the old group (p=0.298). Twenty-six young pa- tients (36.1%) and 63 (41.2%) old patients had abdominal pain (p=0.469). Six (8.3%) young patients and 21 old pa- tients (13.7%) had bloody diarrhea (p=0.246). Leukocytosis (41.7% vs. 67.3%, p=0.000) and hypoalbuminemia (58.3%

vs. 76.5%, p=0.005) were more common in old patients.

However, hypotension (30.6% vs. 29.4%, p=0.861), hypo- kalemia (32.4% vs. 31.4%, p=0.878), and renal dysfunction

(25.0% vs. 26.1%, p=0.855) did not differ significantly be- tween groups (Table 2).

Old patients had a higher mean severity score (2.7 vs. 2.9, p=0.036), and a greater percentage in the old group had a severity score of ≥3 points (77.8% vs. 89.5%, p=0.018).

Table 3. Clinical Outcomes in the Young and Old Study Groups

Variable Young group (n=72)

Old group (n=153) p-value Failure of 1st line treatment 17 (23.6) 58 (37.9) 0.034

Recurrence 6 (8.3) 23 (15.0) 0.162

Time to recurrence (day) 33.6±8.2 25.1±11.0 0.479 Associated mortality 1 (1.4) 9 (5.9) 0.127 Values are presented as n (%) or mean±SD.

Young group, less than 65 years; old group, 65 years and up.

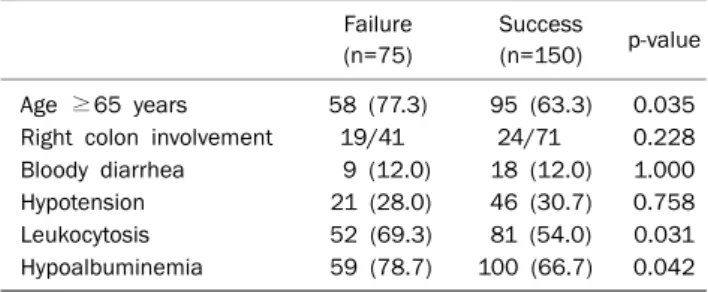

Table 4. Clinical Comparisons of Patients by Response to First Line Treatment

Failure (n=75)

Success

(n=150) p-value Age ≥65 years 58 (77.3) 95 (63.3) 0.035 Right colon involvement 19/41 24/71 0.228 Bloody diarrhea 9 (12.0) 18 (12.0) 1.000

Hypotension 21 (28.0) 46 (30.7) 0.758

Leukocytosis 52 (69.3) 81 (54.0) 0.031

Hypoalbuminemia 59 (78.7) 100 (66.7) 0.042 Values are presented as n (%) or n only.

Table 5. Risk Factors for First Line Treatment Failure

Parameter OR 95% CI p-value

Age ≥65 years 0.157 0.300-1.105 0.097

Leukocytosis 1.716 0.939-3.316 0.079

Hypoalbuminemia 1.498 0.761-2.951 0.242

Metronidazole was used most commonly as an initial treat- ment (70 [97.2%] vs. 135 [88.2%]) in both groups. However, the rate of vancomycin use as an initial treatment was greater in the old group (2 [2.8%] vs. 18 [11.8%], p=0.027), and fail- ure of first line treatment was more common in the old group (17 [23.6%] vs. 58 [37.9%]; p=0.034). Recurrence rates were 8.3% (6/72) and 15.0% (23/153) in the young and old groups, respectively, which was not a significant difference (p=0.162). From initial infection to recurrence, the period was not significantly different (33.6±8.2 in young group vs.

25.1±11.0 in old group, p=0.479). Mortality rates attributed to CDI were not significantly different (1 [1.4%] vs.9 [5.9%];

p=0.127) (Table 3). During the study period, a 35-year-old fe- male patient underwent surgery due to severe refractory CDI, and achieved a good condition without evidence of recur- rence.

An age of ≥65 years, leukocytosis, hypoalbuminemia were found to be associated with first line treatment failure (Table 4). However, multivariate analysis failed to identify a risk factor significantly associated with treatment failure (Table 5).

DISCUSSION

CDI is a serious disease that is associated with significant morbidity and mortality, with incidence that has increased over last years.9 Advanced age, usually described as above 65 years, is associated with greater risk of CDI, with more se- vere disease, and a more frequent recurrence, resulting in higher morbidity and mortality.9,10,16,17 The present study shows that advanced age is associated with more severe dis- ease and failure to respond to first line treatment. However, no significant intergroup difference was found for recurrence or mortality rates.

In a previous study, advanced age was observed to be as-

sociated with CDI severity. The other variables associated with complicated disease were leukocytosis, renal failure, hy- poalbuminemia, the presence of small bowel obstruction or ileus, and an imaging study showing colorectal inflam- mation.18 The relationship between leukocytosis and greater disease severity19 was described in initial reports of B1/NAP1 strain outbreaks.8,10 In the present study, leukocy- tosis and hypoalbuminemia were more common in the old group, which supports the findings that advanced age is a major risk factor of an unfavorable outcome in CDI.9,10,16,17

There was no previous studies about right side colon in- volvement in patients with CDI. However, according to the study of ischemic colitis and ulcerative colitis, right colon in- volvement was associated with severe colitis and poor prognosis.20 We thought that it could be similar in CDI be- cause right colon involvement means more extensive disease. For this reason, the severity of disease in the pa- tients in the old age group was higher in this study.

We found the use of vancomycin as an initial treatment was more frequent in the old group. The best treatment for CDI has not been determined. Many experts suggest vanco- mycin as first-line therapy in older patients, especially for pa- tients with leukocytosis, severe abdominal pain, or an ele- vated creatinine level,21-24 and several studies have con- firmed that oral vancomycin provides higher rates of reso- lution than metronidazole in patients with severe CDI.21

In the present study, the rate of treatment failure was

greater in the old group. In a previous study, in elderly CDI pa- tients, treatment failure on metronidazole occurred fre- quently and appeared to be related to a higher peak WBC count,19 concurrent with our results.

The limitations of the present study include a retrospective design and a small sample size. However, the study is unique as it is the first to compare clinical outcomes of CDI in young and old patients in Korea.

Greater efforts toward prevention would be more effective, especially as this is a nosocomial problem. Previous studies indicate the importance of the protective role played by im- mune response after colonization.25-29 Thus, the decreased immune responsiveness commonly observed in the elderly maybe an important component of CDI development in pa- tients older than 65 years.

A state of immune deficiency contributes to the risk of ad- verse outcomes in elderly patients. The leukocytosis ob- served in such patients at presentation could be indicative of disease severity. Furthermore, thymic involution, an in- crease in natural killer cell numbers, and a decrease in B cell and immune responsive T-cell number are characteristic of the aging process.30-33 Although T cell numbers in peripheral blood remain stable with age, the number of immunores- ponsive virgin CD 95 T cells falls markedly, while the majority of T cells are committed to the containment of endogenous viruses. These age-related changes result in a chronic proin- flammatory state that leaves the host hyporesponsive to neo- antigens30,34,35 and diminishes immunologic responses to in- fectious challenges.

In conclusion, right side colon involvement, leukocytosis, hypoalbuminemia, severe CDI, initial usage of vancomycin, and failure of first line treatment were more common in CDI patients at least 65 years old than in patients less than 65 years old. Furthermore, old age, leukocytosis, and hypo- albuminemia were found to be associated with first line treat- ment failure. We recommend intensive therapy be consid- ered at time of diagnosis in CDI patients of 65 years or older exhibiting leukocytosis and hypoalbuminemia.

REFERENCES

1. Pépin J, Valiquette L, Alary ME, et al. Clostridium difficile-asso- ciated diarrhea in a region of Quebec from 1991 to 2003: a changing pattern of disease severity. CMAJ 2004;171:466-472.

2. Muto CA, Pokrywka M, Shutt K, et al. A large outbreak of

Clostridium difficile-associated disease with an unexpected pro- portion of deaths and colectomies at a teaching hospital follow- ing increased fluoroquinolone use. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2005;26:273-280.

3. Loo VG, Poirier L, Miller MA, et al. A predominantly clonal multi-in- stitutional outbreak of Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea with high morbidity and mortality. N Engl J Med 2005;353:2442- 2449.

4. Kuijper EJ, Coignard B, Tüll P. Emergence of Clostridium diffi- cile-associated disease in North America and Europe. Clin Microbiol Infect 2006;12 Suppl 6:2-18.

5. Kuijper EJ, van Dissel JT, Wilcox MH. Clostridium difficile: chang- ing epidemiology and new treatment options. Curr Opin Infect Dis 2007;20:376-383.

6. Ricciardi R, Rothenberger DA, Madoff RD, Baxter NN. Increasing prevalence and severity of Clostridium difficile colitis in hospi- talized patients in the United States. Arch Surg 2007;142:

624-631; discussion 631.

7. Cohen SH, Gerding DN, Johnson S, et al. Clinical practice guide- lines for Clostridium difficile infection in adults: 2010 update by the society for healthcare epidemiology of America (SHEA) and the infectious diseases society of America (IDSA). Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2010;31:431-455.

8. McEllistrem MC, Carman RJ, Gerding DN, Genheimer CW, Zheng L. A hospital outbreak of Clostridium difficile disease associated with isolates carrying binary toxin genes. Clin Infect Dis 2005;40:

265-272.

9. McDonald LC, Owings M, Jernigan DB. Clostridium difficile in- fection in patients discharged from US short-stay hospitals, 1996-2003. Emerg Infect Dis 2006;12:409-415.

10. Pépin J, Valiquette L, Cossette B. Mortality attributable to noso- comial Clostridium difficile-associated disease during an epi- demic caused by a hypervirulent strain in Quebec. CMAJ 2005;173:1037-1042.

11. Dubberke ER, Reske KA, Olsen MA, McDonald LC, Fraser VJ.

Short- and long-term attributable costs of Clostridium diffi- cile-associated disease in nonsurgical inpatients. Clin Infect Dis 2008;46:497-504.

12. Ghantoji SS, Sail K, Lairson DR, DuPont HL, Garey KW. Economic healthcare costs of Clostridium difficile infection: a systematic review. J Hosp Infect 2010;74:309-318.

13. Karas JA, Enoch DA, Aliyu SH. A review of mortality due to Clostridium difficile infection. J Infect 2010;61:1-8.

14. Yoon SY, Jung SA, Na SK, et al. What's the clinical features of col- itis in elderly people in long-term care facilities? Intest Res 2015;13:128-134.

15. Surawicz CM, Brandt LJ, Binion DG, et al. Guidelines for diag- nosis, treatment, and prevention of Clostridium difficile infections. Am J Gastroenterol 2013;108:478-498; quiz 499.

16. Miller M, Gravel D, Mulvey M, et al. Health care-associated Clostridium difficile infection in Canada: patient age and infect- ing strain type are highly predictive of severe outcome and mortality. Clin Infect Dis 2010;50:194-201.

17. Simor AE. Diagnosis, management, and prevention of Clostridium difficile infection in long-term care facilities: a review. J Am Geriatr Soc 2010;58:1556-1564.

18. Shivaprakasha S, Harish R, Dinesh KR, Karim PM. Aerobic bacte- rial isolates from choledochal bile at a tertiary hospital. Indian J Pathol Microbiol 2006;49:464-467.

19. Cober ED, Malani PN. Clostridium difficile infection in the

"oldest" old: clinical outcomes in patients aged 80 and older. J Am Geriatr Soc 2009;57:659-662.

20. Flobert C, Cellier C, Berger A, et al. Right colonic involvement is associated with severe forms of ischemic colitis and occurs fre- quently in patients with chronic renal failure requiring hemo- dialysis. Am J Gastroenterol 2000;95:195-198.

21. Zar FA, Bakkanagari SR, Moorthi KM, Davis MB. A comparison of vancomycin and metronidazole for the treatment of Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea, stratified by disease severity. Clin Infect Dis 2007;45:302-307.

22. Gerding DN. Metronidazole for Clostridium difficile-associated disease: is it okay for Mom? Clin Infect Dis 2005;40:1598-1600.

23. Bartlett JG. The case for vancomycin as the preferred drug for treatment of Clostridium difficile infection. Clin Infect Dis 2008;46:1489-1492.

24. Musher DM, Aslam S, Logan N, et al. Relatively poor outcome af- ter treatment of Clostridium difficile colitis with metronidazole.

Clin Infect Dis 2005;40:1586-1590.

25. Sambol SP, Merrigan MM, Tang JK, Johnson S, Gerding DN.

Colonization for the prevention of Clostridium difficile disease in hamsters. J Infect Dis 2002;186:1781-1789.

26. Shim JK, Johnson S, Samore MH, Bliss DZ, Gerding DN. Primary symptomless colonisation by Clostridium difficile and de- creased risk of subsequent diarrhoea. Lancet 1998;351:633- 636.

27. Wilcox MH. Descriptive study of intravenous immunoglobulin for the treatment of recurrent Clostridium difficile diarrhoea. J Antimicrob Chemother 2004;53:882-884.

28. Kyne L, Warny M, Qamar A, Kelly CP. Asymptomatic carriage of Clostridium difficile and serum levels of IgG antibody against tox- in A. N Engl J Med 2000;342:390-397.

29. Giannasca PJ, Warny M. Active and passive immunization against Clostridium difficile diarrhea and colitis. Vaccine 2004;22:848-856.

30. Sansoni P, Vescovini R, Fagnoni F, et al. The immune system in extreme longevity. Exp Gerontol 2008;43:61-65.

31. Biagi E, Candela M, Fairweather-Tait S, Franceschi C, Brigidi P.

Aging of the human metaorganism: the microbial counterpart.

Age (Dordr) 2012;34:247-267.

32. Aspinall R, Andrew D. Thymic involution in aging. J Clin Immunol 2000;20:250-256.

33. Hsu HC, Mountz JD. Metabolic syndrome, hormones, and main- tenance of T cells during aging. Curr Opin Immunol 2010;22:

541-548.

34. Almanzar G, Schwaiger S, Jenewein B, et al. Long-term cytome- galovirus infection leads to significant changes in the composi- tion of the CD8+ T-cell repertoire, which may be the basis for an imbalance in the cytokine production profile in elderly persons.

J Virol 2005;79:3675-3683.

35. Moro-García MA, Alonso-Arias R, López-Vázquez A, et al.

Relationship between functional ability in older people, immune system status, and intensity of response to CMV. Age (Dordr) 2012;34:479-495.