다음과 같은 조건을 따라야 합니다: l 귀하는, 이 저작물의 재이용이나 배포의 경우, 이 저작물에 적용된 이용허락조건 을 명확하게 나타내어야 합니다. l 저작권자로부터 별도의 허가를 받으면 이러한 조건들은 적용되지 않습니다. 저작권법에 따른 이용자의 권리는 위의 내용에 의하여 영향을 받지 않습니다. 이것은 이용허락규약(Legal Code)을 이해하기 쉽게 요약한 것입니다. Disclaimer 저작자표시. 귀하는 원저작자를 표시하여야 합니다. 비영리. 귀하는 이 저작물을 영리 목적으로 이용할 수 없습니다. 변경금지. 귀하는 이 저작물을 개작, 변형 또는 가공할 수 없습니다.

Sun Aee Kim

The Graduate School

Yonsei University

Department of Nursing

A Dissertation

Submitted to the Department of Nursing

and the Graduate School of Yonsei University

in partial fulfillment of the

requirements for the degree of

Doctor of Philosophy

옳~Ú:‘ ~

1l

1csis Supervisor: Tae Wha Lee

&ι- 빠μ

꺼lesisCommiltee Member : Suc

Ki

m

빼ε-.(Cι~

Th

esis

Comm~ttee

Mcmber :

Hyu뼈

πlesis

Committee Member : Seung Eun Lee

r\'l>Y41Þ낯~ y니

I ‘~πlesis

Coinmittee Member : Soyoung Yu

The Graduate School

Y onsei University

June 2020

moments of despair, but I believe that these difficulties have carried me where I am now. I am grateful for helping hand that has made finishing this paper possible.

I am deeply grateful to Dean Lee Tae-wha, who has offered me guidance when I was lost and set me in the right direction when I was feeling drained and helpless. She has helped me tremendously with a piercing insight in the important features of this study and made this day possible for me. I will forever cherish the moments when she welcomed me to her help, encouraged me, and gave me the confidence to push through nerve-racking experiences.

I am grateful to Professor Kim Sue for being patient with me as I caught up with things slowly, going over everything with me in detail, and guiding me in the right direction every time I went off course. I am also indebted to Professor Lee Seung-eun for motivating me to take the hard route, continue learning, and maintain a balanced view, Professor Hyun-ok Do for giving me courage, hope, and unreserved compliments throughout my privileged acquaintance with her from the JCI accreditation to the thesis reviews, and Professor Yu Soyoung , who I have known for long now, for always encouraging and supporting me through hard times and helping me with everything from the structure of the study to its small details.

familiarize with the subject, and most importantly, Director of Administration Kwon Ki-chang for providing moral support and creating an environment for me to focus on finishing the thesis.

Many thanks to Director of Nursing Lee Seung-shin for always giving me the unchanging support even after leaving the department, Chief Park Min-jung for being such dependable presence anywhere and under any circumstance, and Team Leaders Lim Hee-joo , Ko Hyang-ah, and Choi Ho-soon , who shared same views with me and whose understanding and support were felt without a word.

I am thankful to Professor Kim Ji-in , a friend and a mentor, my friend Shin Kyung-ah for sharing all of my joys and sorrows during the study, and Mi-jin, Ju-young, and Team Leader Jun Myung-hwa. I would like to thank my old friend Eun-mi, Seung-joo , Hye-ryung , and Myung-hwa who spoke more through hearts than with words. Thanks to Professors Lee Ju-ri and Kim Eunmi for being patient with me when I was not as fast a learner as other younger friends, encouraging me, and helping with my work as if it were their own, my precious graduate classmates Kim Young-man, Jung Hye-jung, Han Nam-kyeong , and Choi Yeon-ok , and Kim Myung-shin.

literature search from the start of my graduate study.

Though I cannot mention the name of everyone who has helped me due to the page limit, I am aware that I would not be where I am without the co-workers, senior members, and friends who always stood by me and gave me support. I would like to take this space to extend my gratitude to each and every one of them.

Lastly, special thanks to my father who passed without seeing his daughter complete the thesis, my mother for giving emotional support out of concerns for her daughter studying, and the rest of my family.

Many thanks to Young-kyu, my loving son and a high school senior, for understanding, respecting, and being proud of his mother who was constantly busy with her work and study, and my husband for giving me courage and sacrificing so much to support me financially and time-wise.

This paper was completed with the help of so many others, and I will hold on to and cherish the lessons I have learned from them and as I prepare my way toward the future.

Sun Aee, Kim July, 2020

CONTENTS ... i LIST OF TABLES ... v LIST OF FIGURES ... ⅵ LIST OF APPENDICES ... ⅵ ABSTRACT ... ⅶ Ⅰ. INTRODUCTION ... 1 A. Background ... 1 B. Purpose ... 5 C. Definitions of Terms ... 6 Ⅱ. LITERATURE REVIEW ... 11

A. Nurse`s experience and Patient Safety Incidents ... 11

B. Quality of Work Life ... 14

Ⅳ. METHODS ... 28 A. Design ... 28 B. Quantitative study ... 29 1. Participants ... 29 2. Measurements Tool ... 32 3. Data collection ... 44 4. Data analysis ... 46 C. Qualitative study ... 47 1. Participants ... 47 2. Interview Question ... 47 3. Data collection ... 48 4. Data analysis ... 49

5. Consideration for Rigor... 50

2. Patient Safety Incidents in Relation to Characteristics of Participants ... 55

2.1 Type of Patient Safety Incidents ... 55

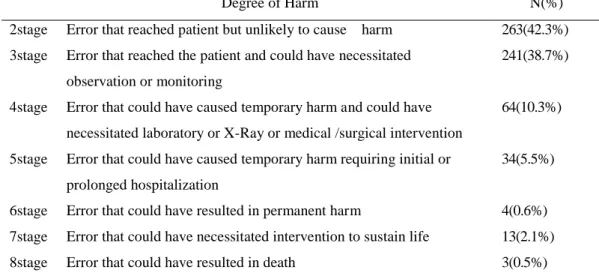

2.2 The Degree of Harm of Patient Safety Incidents ... 56

2.3 Duration of Stress Experienced Following Patient Safety Incidents ... 57

3. Descriptive Statistics of Observed Variables ... 58

4. Employee Health, Organizational Health, and Quality of Work Life in Relation to Participants’ Characteristics ... 60

5. Difference of Employee Health, Organizational Health, and Quality of Work Life by Patient Safety Incidents ... 64

5.1 Employee Health, Organizational Health, and Quality of Work Life relation to the Duration of Stress ... 64

5.2 Employee Health, Organizational Health, and Quality of Work Life in Relation to the Degree of Harm ... 66

5.3 Employee Health, Organizational Health, and Quality of Work Life in Relation to the Frequency of Patient Safety Incidents ... 68

6. Correlation among the measured variables ... 70

Theme 2. The Quality of Work Life Related to Patient Safety Incidents ... 84

C. Integration of the Findings from the Quantitative and Qualitative Studies ... 94

Ⅵ. DISCUSSION ... 97

A. The Quality of Work Life of Nurses After Experiencing Patient Safety Incidents ... 97

B. Factor of Influencing Quality of Work Life ... 100

Ⅶ. CONCLUSION AND SUGGESTIONS ... 110

1. Conclusion ... 110

2. Suggestions ... 111

REFERENCE ... 112

APPENDICES ... 121

Table 4. Reliability of the measurements ... 43

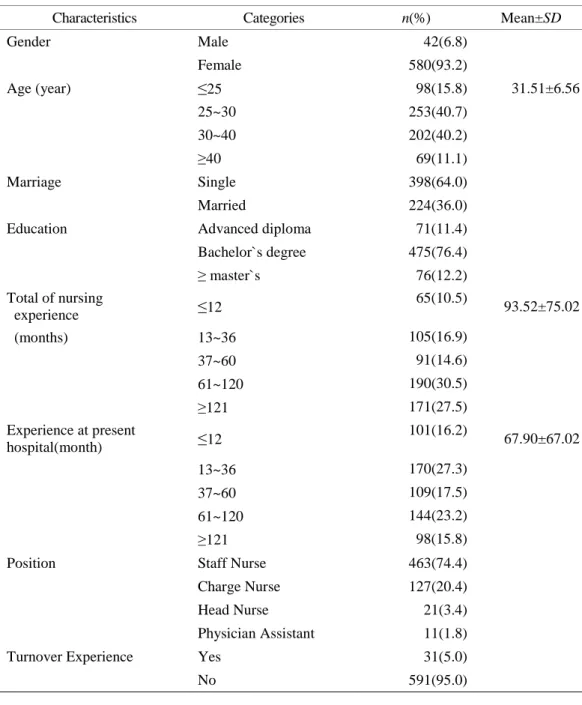

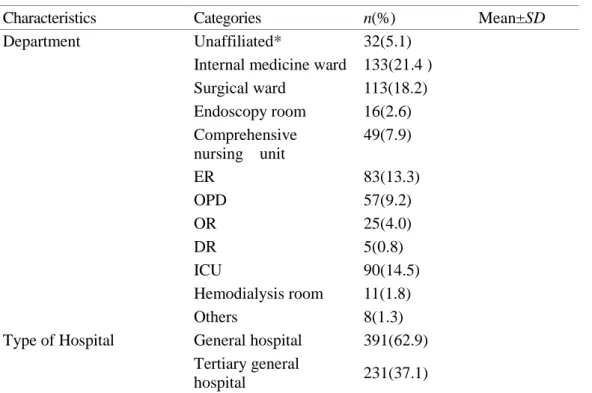

Table 5. Socio-demographic characteristics of participants ... 53

Table 6. Type of patient safety Incidents ... 55

Table 7. The degree of harm of patient safety incidents ... 56

Table 8. Duration of Stress Experienced following patient Safety Incidents ... 57

Table 9. Descriptive Statistics of Observed Variables ... 59

Table 10. Employee Health, Organizational Health, and Quality of Work Life in Relation to Participants’ Characteristics ... 62

Table11. Employee Health, Organizational Health, and Quality of Work Life relation to the Duration of Stress ... 65

Table 12. Employee Health, Organizational Health, and Quality of Work Life relation to the degree of Harm ... 67

Table 13. Employee Health, Organizational Health, and Quality of Work Life in Relation to the Frequency of Patient Safety Incidents ... 69

Table 14. Correlation among the measured variables ... 70

Table 15. Factor of Influencing Quality of Work Life ... 72

Table 16. Characteristics of study participants ... 74

Table 17. Content Analysis of the Quality of Work Life of Nurses with Patient Safety Incident Experience ... 75

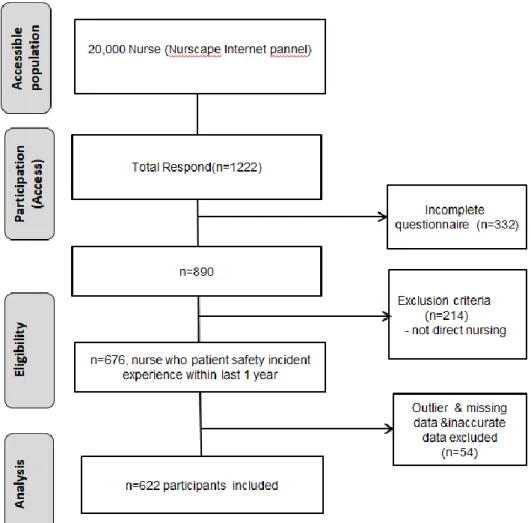

Figure 4. Flow chart of study participants ... 31

LIST OF APPENDICES

Appendix 1. Result of IRB approval ... 121Appendix 2. Explanation and consent form of study (online) ... 124

Appendix 3. Explanation and consent form of study (quantitative study) ... 127

Appendix 4. Questionnaire (Quantitative study)... 130

American Institute of Medicine (IOM) in 1999 was followed by the growing interest and effort in patient safety. Patient safety issues have been reflected in major health and welfare policies. Nonetheless, the WHO (2016) reported 8-12% chance of adverse incidents happening among hospitalized patients in Europe, and Rafter et al. (2015) estimated that 4-17% of hospitalized patients are in some way involved in adverse incidents. Health care providers experience psychological trauma when involved in a patient harm due to an unexpected event or a medical error. Physical, emotional, and professional life of healthcare providers as well as their quality of work life are deeply associated with such incident.

The purpose of this study was to (1) investigate in a quantitative study the quality of work life of nurses involved in patient safety incidents within the framework of the Culture-Work-Health Model developed by Peterson & Wilson (2002), (2) examine in a qualitative study the personal experiences of nurses and their quality of work life after being involved in patient safety incidents, and (3) integrate the findings of the two studies to formulate a comprehensive understanding of the quality of work life of nurses involved in patient safety incidents.

The quantitative study was conducted with 622 participants through an online survey from March 10 to 18, 2020. The quantitative study were examined using

The major findings of the studies are as follows. First, higher scores for employee health and organizational health were associated with longer terms of physical, psychological, and professional stress caused by patient safety incidents. The quality of work life score for the nurses without stress symptoms was observed to be the highest, and lower quality of work life scores were associated with stress lasting longer than 6 months (F=8.496, p<.001). Second, the multiple linear regression analysis performed to identify factors associated with the quality of work life of nurses involved in patient safety incidents was found to be at 46% (Adjusted R2 = .452). The significant influence

factors of the quality of work life of nurses were in the order of high to low significance, resonant leadership (β=.352 t=8.271 p< .001), just culture (β=.203 t=4.601, p< .001), organizational support (β=.126 t=3.046, p < .01), organizational health (β =-.113 t=-2.975, p< .01), and the nurse’s total work experience (β=.119 t=2.187, p< .05).

The qualitative study emerged 2 themes—a work culture in which blame and trust co-exist and the quality of work life after experiencing patient safety incidents—and 7 categories—‘closedness of work atmosphere,’ ‘closedness of work atmosphere,’ ‘Patient safety incidents report preparation depends on the degree of harm and the unit atmosphere,’ ‘constructive changes after the incidents,’ ‘physical, psychological, and

culture, and organizational support are important factors of not only employee health but also organizational health and quality of work life. In order to improve the quality of work life of its nurses, an institution must shift its focus away from blaming and punishment the individuals involved in patient safety incidents to understanding the circumstances in which the incidents happened, finding the root causes, act improvement, and creating a culture of learning from errors.

In addition, institutions must develop a clear understanding of their just culture and the physical, psychological, and professional distress experienced by nurses involved in patient safety incidents and continue their efforts in developing strategies to harness the strengths and reinforce the weaknesses of their culture to improve patient safety and the quality and patient safety of healthcare services will be improved as well as the quality of work life for nurses.

With little literature available on the use of the CWHM in investigating the work life of nurses involved in patient safety incidents, the results of this study in the context of the prior studies and the CWHM will provide preliminary data for developing strategies to help nurses manage stress and improve their quality of work life after patient safety incidents.

I. INTRODUCTION

A. Background

The recent increase in knowledge and interest in health care has brought patient safety and the quality of healthcare services to light. In particular, there has been growing attention to improving patient safety culture after the publication of the Institute of Medicine(IOM) report ‘To Err is Human: Building a Safer Health System’ in 1999, and related issues have been reflected in important health policies (Lee & Lee, 2009). Despite the effort, adverse events occur daily in health care contexts. Large-scale international reviews of patient charts estimated that 4-17% of hospital admissions are associated with adverse events (Rafter et al., 2015). In the European Union member states, estimated 8– 12% adverse event rates among hospitalizations were reported (WHO, 2016). Recent data from the U.S. have also shown that 210,000 to 440,000 preventable deaths related to adverse events occur annually (James, 2013).

Experiencing a patient death or harm due to an unexpected patient safety event or medical error causes psychological trauma and various personal, emotional, and professional problems in health care providers (Scott et al., 2009). 14-30% of health care providers are directly or indirectly involved in patient safety incidents, and about 50% experience at least one patient safety incident during their career. All health care providers have the potential for falling victim to adverse events or medical errors (Edrees,

Paine, Feroli, & Wu, 2011). Symptoms experienced by healthcare providers after a patient safety incident include sleep disorder, burnout, reduced job satisfaction, feelings of guilt and anger, and fear of punishment (Rassin, Kanti, & Silner, 2005; Scott et al., 2009; Waterman et al., 2007; Wu, 2000).

Therefore, if not abated or treated, the symptoms and reactions caused by patient safety incidents, can harm the emotional and physical health of health care providers and subsequently compromise patient safety, and further increases the likelihood of committing errors and providing suboptimal care (Quillivan, Burlison, Browne, Scott, & Hoffman, 2016). These conditions lower the quality of health care services, continue to pose threats to patient safety (Abbasi et al., 2017), and eventually undermine the quality of healthcare services and can inflict financial damage on the hospital (Chard, 2010; Shanafelt et al., 2010).

Quality of work life is determined by the emotions and feelings that employees have toward their work and is improved through a synergetic relationship among co-worker and supervisor support, teamwork and communication, and organizational characteristics (Abbasi et al., 2017). Quality of work life affects not only job satisfaction but also organizational productivity and self-actualization of individual employees (Mosadeghrad, Ferlie, & Rosenberg, 2011).

Abbasi et al.(2017) identified the supervisor’s leadership and management style, decision-making latitude, shift working, salary and benefits, relationship with colleagues, workload and work strain, and demographic characteristics as factors affecting the quality

of work life. Other factors that have been studied include organizational culture, clinical competence, burnout, and social support (Abbasi et al., 2017; Ghouligaleh, Farahani, Karahroudy, Pourhoseingholi, & Mojen, 2018; Gifford, Zammuto, & Goodman, 2002; Hsu, 2016; Thakre, Thakre, & Thakre, 2017).

Since 2010, korea studies have been conducted to relate organizational culture to quality of work life and organizational effectiveness (An, Yom, & Ruggiero, 2011). Additionally, (Abbasi et al., 2017) presented organizational culture, social support, employee health, and organizational health as influence factors of the quality of work life of clinical nurses.

The quality of work life of nurses is closely related to health care services and patient safety (Kowitlawkul et al., 2018). Patient safety incidents lower the quality of work life of nurses by causing physical and psychological distress, which leads to turnover intention or absenteeism (Burlison, Quillivan, Scott, Johnson, & Hoffman, 2016). It is crucial to manage the quality of work life of nurses who have experienced patient safety incidents in order to maintain the quality of health care services. (Abbasi et al., 2017) stated that organizational support—a strong patient safety culture, colleagues support, supervisor support, institutional support—can alleviate distress from patient safety incidents. Another study shows that supportive interactions with colleagues and supervisors can help nurses cope with the stress after experiencing patient safety incidents (Burlison et al., 2016).

alleviated by a non-punitive work environment, openly discussing about incidents, exchanging incident-related information with co-workers, and constructive feedbacks from the supervisor or organization (Seys et al., 2013). Another study found that creating a just culture encompassing the above-mentioned elements is a primary factor of reducing the distress following patient safety incidents (Joesten, Cipparrone, Okuno-Jones, & DuBose, 2015). Additionally, In the Just culture, providing support at leadership and management levels helps them cope with the feelings of guilt and shame associated with medical errors (Denham, 2007; Joesten et al., 2015; Scott et al., 2010).

Many studies have emphasized the support needed for health care providers who suffer from distress caused by patient safety incidents, but few examine the effect of patient safety incidents on the work life of nurses (Schelbred & Nord, 2007).

Hence by using a mixed methods approach, this study aimed to: 1) investigate in a quantitative study the correlation between each of the variables within the framework of the Culture-Work-Health Model developed by Peterson & Wilson (2002) and the quality of work life of nurses who experienced patient safety incidents; 2) closely examine in a qualitative study the personal experience of nurses following patient safety incidents and its effect on their quality of work life. By combining the findings of the above two studies, this study developed a comprehensive understanding of the quality of work life of nurses who experienced patient safety incidents.

The results of this study will serve as evidence in developing stress management programs and intervention strategies aimed at helping nurses manage their physical and

psychological symptoms and improve quality of work life after experiencing patient safety incidents.

B. Purpose

The purpose of this study was to identify factors affecting the quality of work life of nurses who have experienced patient safety incidents. The specific aims of this study were as follows;

(1) To describe the effect of just culture, resonant leadership, organizational support, employee health, and organizational health on the quality of life of nurses who experienced patient safety incidents.

(2) To understand the significance of physical and psychological symptoms, support, and quality of work life after patient safety incidents through in-depth interview

(3) To develop a comprehensive understanding of the quality of work life of nurses who have experienced patient safety incidents through comparative analyses of qualitative and quantitative results.

C. Definition of Terms

1. Patient Safety Incidents

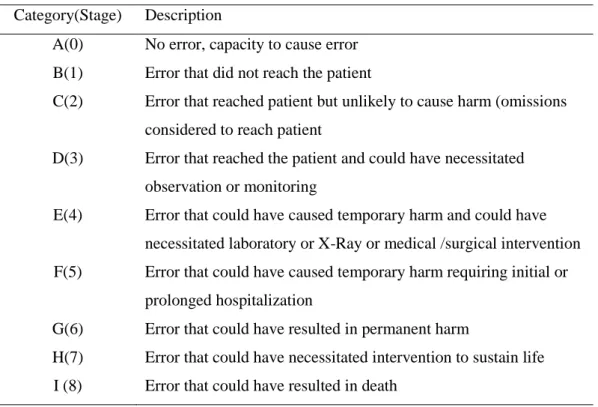

Patient safety is defined as an absence of preventable harm to a patient during the process of patient care (WHO, 2009). The National Coordinating Council for Medication Error Reporting and Prevention (NCC MERP) has developed categories for classifying medication errors. The NCC MERP index considers factors such as whether the error reached the patient and, if the patient was harmed, to what degree. In this study, patient safety incidents refer to events that fall within the categories C(stage2) through I (stage8) among the 9 Categories of Medication Error Classification, which have been taken from the NCC MERP index and modified according to the Korea Patient Safety Reporting &learning System (KOPs). Table 1 below explains the modified categories of medication error classification.

Table 1. Categories of Medication Error Classification Category(Stage) Description

A(0) No error, capacity to cause error B(1) Error that did not reach the patient

C(2) Error that reached patient but unlikely to cause harm (omissions considered to reach patient

D(3) Error that reached the patient and could have necessitated observation or monitoring

E(4) Error that could have caused temporary harm and could have necessitated laboratory or X-Ray or medical /surgical intervention F(5) Error that could have caused temporary harm requiring initial or

prolonged hospitalization

G(6) Error that could have resulted in permanent harm

H(7) Error that could have necessitated intervention to sustain life I (8) Error that could have resulted in death

2. Just Culture

Just culture defined as organizational culture based on trust. In a just culture environment, all parties involved in a patient safety incident trust that they are entitled to just and fair treatment (Reason, 1998). In this study, just culture was measured by scores provided according to the Just Culture Assessment Tool (JCAT) developed by Petschonek et al. (2013). A high score indicates a high level of just culture in the responder’s organization.

3. Resonant Leadership

Resonant leadership is supervisors’ ability to effectively manage emotions of their own and others in the workplace. It is a measure of leaders’ emotional intelligence and their ability to build strong relationships of trust with employees and create a climate of optimism (Squires, Tourangeau, & Doran, 2010). In this study, resonant leadership was measured by the Resonant Leadership Scale developed by Cummings et al. (2010). A high score indicates a high level of resonant leadership.

4. Organizational Support

Organizational support indicates a level of trust that employees have toward their organization. Employees’ perception of organizational support is based on the level of care, attention, and recognition, and compensation given to them by their organization (Wayne, Shore, & Liden, 1997). In this study, organizational support was measured by

scores provided on colleague support, supervisor support, and institutional support according to the Second Victim Experience and Support Tool. A high score indicates a high level of organizational support perceived by the responder.

5. Employee Health

Employee health refers to conditions of physical and mental sickness, absenteeism, and fatigue found in employees (Peterson & Wilson, 2002). In this study, employee health was defined as psychological and physical distress and reduced professional self-efficacy after patient safety incidents. Employee health was measured by scores provided on 4 items regarding psychological distress, 4 regarding physical distress, and 4 regarding reduced professional self-efficacy from SVEST. A high score indicates a low level of employee health.

6. Organizational Health

Organizational health refers to the well-being of the corporate whole (Peterson & Wilson, 2002). In this study, organizational health was measured by scores provided on 3 items - 2 regarding turnover intention and 1 regarding absenteeism - from the Second Victim Experience and Support Tool (SVEST). A high score indicates a low level of organizational health.

7. Quality of Work Life

Quality of work life is defined as the emotions and feelings that employees have toward their work (Abo-Znadh, 1998). In this study, quality of work life was measured according to the Work-Related Quality of Life scale developed by Van Laar et al. (2007). A high score indicates a high quality of work life.

II. Literature Review

The purpose of this literature review is as follows: first, explore the experienced symptoms after patient safety incidents; second, present factors affecting quality of work life; and third, identify the relationship among key variables based on prior studies of the effect of patient safety incidents on the quality of work life of nurses.

A. Nurse`s experience and Patient Safety Incidents

Although hospitals focus on improving patient safety and the quality of their healthcare services, witnessing a patient harm or death due to an unforeseen patient safety incident is an unavoidable reality for health care providers at many medical sites (Quillivan et al., 2016).

According to the WHO (2016), inpatients have an 8-12% chance of experiencing adverse events in the hospital, and De Vriese et al. (2008) report that the adverse event rate is 9.2%, meaning one in nearly 10 inpatients experience a patient safety incident. Although Korea does not have accurate statistics on the occurrence of patient safety incidents, the cumulative number of patient safety incidents reported in the Korea Patient Safety Reporting & Learning System (KOPs) is 19,360 since the implementation of the Patient Safety Act on July 29, 2016 (Annual Patient Safety Statistics, 2018).

also leads to many difficulties for health care providers. Especially incidents caused by unforeseen events or medical errors can cause psychological trauma and personal, emotional, and professional problems (Scott et al., 2009; Rassin et al., 2005; Waterman et al., 2007).

Every health care provider has the potential to fall victim to adverse events or medical errors. 14-30% of health care providers reported in a study that they had experienced patient safety incidents within the last year (Scott et al., 2009). 30% of health care providers in the U.S., 40% in Canada, and 69% of nurses and 77% of doctors in Spain mentioned in a different study that they experienced physical and psychological distress after being involved in patient safety incidents within the past five years (Mira et al., 2017). Another study found that about 50% of health care providers suffer patient safety incidents at least once during their career ( Edrees et al., 2011).

Responses and symptoms they experience following patient safety incidents include sleep disorder (Scott et al., 2009; Rassin et al., 2005; Waterman et al., 2007), burnout (Prins et al., 2009; West et al., 2015), reduced job satisfaction ( Scott et al., 2009; Waterman et al., 2007), feelings of guilt, anger, and shame (Rassin et al., 2005; Waterman et al., 2007; Harrison et al., 2015), and fear of punitive actions, job loss, and litigation (Scott et al., 2009; Rassin et al., 2005). Involvement in a serious near-miss patient safety incident or witnessing a patient harm can decrease job confidence and job satisfaction and cause anxiety, sleep disorder, and work-related stress in health care providers (Edrees, 2014; Waterman et al., 2007).

Burlison et al. (2016) stated that the physical and psychological distress experienced after patient safety incidents affect the well-being of nurses, their turnover intention and absenteeism, which are in turn likely causes of subsequent medical errors and pose threats to patient safety.

Chan et al. (2017) and Burlison et al. (2016) showed that forming a strong patient safety culture and providing sufficient support are important elements in alleviating the trauma caused by patient safety incidents and helping recovery. However, research on symptoms and reactions after patient safety incidents is still minimal in the korea setting. Only a handful of existing literature includes a study of operating room nurses who suffer from depression, guilt, and high emotional stress due to nursing and medical errors (Jeon & Lee, 2014), a phenomenological study of nurses’ experiences of patient safety incidents (Lee, Kim, & Kim, 2014), and a study of the effect of second victim experiences on the third victim. (Kim et al., 2017). Nurses are important caregivers directly responsible for patient safety at the forefront of medical practice, so studying their experiences is crucial in preparing for appropriate organizational management after patient safety incidents.

B. Quality of Work Life

Over the past two decades, health-related studies have examined the quality of life of patients as a predictor of their treatment results (Kowitlawkul et al., 2018). However, the result of patient treatment is dependent on not only clinical care and intervention, but also the quality of work life of nurses and their work-life balance (Lee, Dai, Park, & McCreary, 2013).

Since nurses are a major human resource that accounts for more than half of the workforce in medical institutions, their quality of work life will directly or indirectly affect patient safety and quality of care (Kowitlawkul et al., 2018). Also, since nurses spend a significant portion of their time at work, their quality of life is significantly affected by their quality of work life (Kim & Sung ,2010).

Improving quality of work life is an important prerequisite for recruiting and retaining competent nurses and ensuring patient safety (Sadat, Aboutalebi, & Alavi, 2017). There is a growing consensus that it is essential to improve the quality of work life of nurses and create and maintain the right working conditions for them to provide quality patient care (Brooks et al., 2007).

The term quality of work life was first introduced in 1930 and broadly used to refer to the quality of life within work environments. However, there was no clear agreement on how to define the term exactly (Easton & Van Laar, 2013). In one of many studies that presented models for understanding quality of work life, Hackman and Oldham (1974) suggested that improving quality of work life involves providing

conditions for employees to experience psychological growth, and called attention to factors such as the nature of work, job autonomy, and feedback. Easton & Van Laar (2013) showed that quality of work life is affected by the nature of work and external factors such as wages, working hours, and working conditions.

Quality of work life is defined as the emotions or feelings that employees have toward their work (Abo-Znadh,1998). Mosadeghrad (2011) defined quality of work life as employees’ overall satisfaction with their work life, which can be reduced by factors such as lack of recognition and emotional exhaustion. Prior studies of the quality of work life of nurses have explored relationships between quality of work life and organizational culture (Gifford et al., 2002; Korner, Wirtz, Bengel, & Goritz, 2015; Thakre et al., 2017), job performance (Abbasi et al., 2017), exhaustion and quality of work life (Hsu, 2016), organizational productivity (Dehghan Nayeri, Salehi, & Ali Asadi Noghabi, 2011), turnover intention (Faraji, Salehnejad, Gahramani, & Valiee, 2017; Kaddourah, Abu-Shaheen, & Al-Tannir, 2018), and social support (Fu et al., 2018; Ghouligaleh et al., 2018). Factors affecting the quality of work life of nurses include leadership and management style, decision-making, shift working, salaries and benefits, relationships with colleagues, demographic variables, workload, and work strain (Vagharseyyedin, Vanaki, & Mohammadi, 2011). Brookes & Anderson (2004) showed that excessive workload and time pressure greatly lower the quality of work life.

On a personal level, quality of work life is related to job satisfaction, work-life balance, safety, health, and well-being. On an organizational level, quality of work life is

related to absenteeism, professional difficulties, employee commitment, and turnover intention (Mitchell, 2012). Another study presented social support and integration as predictors of the quality of life of nurses, as many of them reported that these factors have helped them cope with the stress caused by patient safety incidents (Kowitlawkul et al., 2018).

Although Korea research of the quality of work life of nurses has been minimal, An and Yom (2011) reported significant correlations among the organizational culture of Korean nurses, their quality of work life, and the effectiveness of their organization. Another study of clinical nurses reported that organizational culture, social support, and organization and employee health affect the quality of work life (Kim & Ryu, 2015). Several tools for measuring quality of work life have been developed, and the Work-Related Quality of Life (WRQoL) Scale developed by Van Laar, Edwards, & Easton (2007) in specific measures the quality of work life of health care providers, including nurses. The tool was developed under the guidance of the U.K. NHS (National Health Service) for the purpose of securing advanced personnel and measuring quality improvements in work life.

This measurement tool has been translated into six languages and is widely used in more than 30 countries (Easton & Van Laar, 2013). However, it has never been introduced in Korea. The tool is structured in three dimensions—organizational level, department level, and individual level—and takes into account six key factors—job and career satisfaction (JCS), general well-being (GWB), stress at work (SAW), control at

work (CAW), home-work interface (HWI), and working conditions (WCS). The WRQoL Scale is a reliable tool for measuring the quality of work life of nurses and health care providers, and reflects their stress levels, job satisfaction, work environment, and organizational culture. The tool was deemed suitable in this study for measuring the quality of life of nurses who have experienced patient safety incidents.

The results of the literature review show that the prior studies of the quality of work life of nurses have focused primarily on their work environment and organization culture. Hence the need for an integrated study of the relationships among organizational safety culture, leadership, employee health, organizational health, and quality of work life, and how these factors affect nurses who are coping with the aftermaths of patient safety incidents.

C. Quality of Work Life among Nurses who had Patient Safety

Incidents

1. Just Culture

Organizational culture is defined as the beliefs, values, behavioral patterns and norms shared by organization members (Cooke & Rousseau, 1998). It influences all organizational activities and vice versa (Reiman & Oedewald, 2004). Patient safety is the practice of eliminating, mitigating, and preventing a patient harm caused by medical errors in the course of providing care (National Patient Safety Foundation, 2003). Patient safety culture—i.e. an organizational culture for patient safety—refers to the beliefs, values, and behavioral patterns (Kizer,1999) of an organization as a whole that prevent possible medical errors in the course of providing medical services. A strong patient safety culture is an important precursor of patient safety. Quillivan et al. (2016) found that within a strong patient safety culture, second victim symptoms experienced by health care providers after patient safety incidents are lessened.

A just culture describes a work environment in which individuals believe they will receive fair and just treatment when involved in patient safety incidents (Marx, 2001). Compared to the patient safety culture, perceptions of just culture are focused on reactions to specific adverse events, so that when working to improve just culture, it is helpful to have specific data on staff experiences (Petschonek et al., 2013).

Just culture is a sub-concept of safety culture in which employees are encouraged to report all important events regarding safety without the fear of punitive

actions or blame. It is an organizational culture in which employees trust their organization to fairly evaluate their actions in the event of a patient safety incident. The formation of a just culture must be preceded by a well-established safety culture (Reason, 1998). Within a just culture, employees learn from their errors in a non-punitive work environment through open discussions, sharing their experiences with colleagues, and constructive feedback (Seys et al., 2013).

Lewis et al. (2013) found in an integrated study that nurses who experienced patient safety incidents due to medical errors were either positively or negatively influenced by their work environment and the leadership of their nurse managers. Also, experienced nurses were more attuned to adopting a constructive change in their nursing practice after experiencing patient safety incidents. Sirriyeh et al. (2010) said that an environment in which co-workers and supervisors can be freely consulted reduces the stress experienced by health care providers after patient safety incidents. This means that forming a just patient safety culture must be a priority for medical institutions. However, while much emphasis is laid on the importance of forming a just culture in the process of handling patient safety incidents (Beyea, 2004), there are still few Korea studies examining the relationship between just culture and patient safety incidents.

2. Resonant Leadership

Leadership is an act of influencing people to work toward common goals (Kim, Sung-eun, 2010). Resonant leaders demonstrate a high level of emotional intelligence (EI), i.e. manage the emotions of their own and others effectively; build strong and trusting relationships with employees; and create a climate of optimism that inspires commitment (Squires, Tourangeau, & Doran, 2010). Resonant leadership is a newly emerging concept. This positive relationship-oriented leadership allows nurses to feel respected, recognized, and supported; enhances their effective work performance; and increases their job satisfaction (Cummings, Hayduk, & Estabrooks, 2005). In another study, resonant leadership and interactional justice were associated with the quality of the leader–nurse relationship, which affects safety climate and quality of work life. The study associated resonant leadership directly with a decrease in reported medication errors, turnover intention, and emotional exhaustion (Squires et al., 2010).

In addition, resonant leadership positively affects conflict management among nurses, their job safety, employee health, and job satisfaction, and alleviates anxiety, emotional exhaustion, and stress (Cowden, Cummings, & mcgrath, 2011). Squires et al. (2010) related resonant leadership to healthier leader-nurse relationships, improved safety culture, supportive practice environments, less emotional exhaustion, and lower turnover intention. Wagner et al. (2013) reported the positive relationship between resonant leadership and job satisfaction after examining the effect of resonant leadership, empowerment, and work ethic on job satisfaction and organizational commitment.

Korea research on resonant leadership is still lacking and existing studies only address the relationship between resonant leadership and job satisfaction, turnover intention, and organizational commitment. Therefore, meaningful effort can be made to examine the role of resonant leadership in improving the quality of work life of nurses and helping them cope with second victim symptoms caused by patient safety incidents.

3. Organizational Support

Organizational support refers to a degree to which organization members trust their organization to provide care and recognition (Wayne, Shore, & Liden, 1997). In a workplace setting, organizational support can be provided by institutions, colleagues, and supervisors (Quillivan et al., 2016). Organizational support affects the quality of care, job satisfaction, and psychological well-being (Sharif, Ahadzadeh, & Nia, 2018). Therefore, establishing a supportive work environment for nurses is a crucial step in giving appropriate attention to their psychological well-being.

Lee et al. (2012) observed that nurses who received better support from their organizations, supervisors, and co-workers tended to provide better care to patients. Another study revealed that organizational support from colleagues and supervisors plays an important role in helping nurses recover from their medical errors (Lewis, Baernholdt, & Hamric, 2013). Burlison et al. (2016) also showed that organizational support mitigates second victim symptoms caused by patient safety incidents, helps recovery, and reduces turnover intention and absenteeism. In addition, a study observed that the most desired

organizational support option for nurses was a respected co-worker willing to discuss the details of patient safety incidents with them (Burlison, Scott, Browne, Thompson, & Hoffman, 2014).

Sirriyeh et al. (2010) suggested that health care providers should be encouraged to consult colleagues or supervisors during the coping process after adverse events. Another study reported that a supportive organizational culture greatly affects the quality of work life of health care providers (Dolan, García, Cabezas, & Tzafrir, 2008).

4. Employee Health

In the culture-work-health-model, employee health is determined by conditions such as physical and psychological sickness, absenteeism, and fatigue (Peterson & Wilson, 2002). In this study, employee health was measured by physical and psychological distress and the decline in professional self-efficacy resulting from second victim symptoms after patient safety incidents. After patient safety incidents, nurses experience physical symptoms such as sleep disorder and burnout and psychological symptoms such as feelings of guilt, anger, fear, and shame; depression; loss of self-confidence; and reduced job satisfaction (Burlison et al., 2014). Such physical, psychological, and professional difficulties negatively affect employee health and quality of work life.

5. Organizational Health

Organizational health refers to a state of well-being across the organization. The CWHM provides the theoretical framework for understanding organizational health based on factors such as productivity, performance, competitiveness, profit, and absenteeism (Peterson & Wilson, 2002). Nurses form the largest professional group in hospitals and play the most pivotal role in patient care (Mohamad, 2012). Recruiting and retaining nursing personnel has become a top priority for medical institutions, as their core competence is determined by the performance of their nursing workforce (Kim, 2007).

A study found that the general characteristics of nurses such as age, clinical experience, education level, and economic status serve as predictors of their turnover intention, and that job stress and job satisfaction affect the frequency of turnover (Choice & Hana Sun, 2007). Burlison et al. (2016) examined the effect of patient safety incidents on work performance and showed that second victim experiences affect turnover intention and absenteeism. One of Korean study also showed that patient safety incidents cause various difficulties such as stress, fear, and reduced self-efficacy, which lead to turnover intention or absenteeism and negatively affect the quality of care (Kim, Kim, Lee, & Oh, 2018). Organizational culture is another factor influencing turnover intention, and nurse managers have communicated the need for an effective strategy for building a healthy organizational culture and nursing environment (Faraji et al., 2017). In sum, psychological and physical symptoms experienced after being involved in patient safety incidents result in either turnover or absenteeism and lead to a decline in organizational health and quality of work life.

III. CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK

A. Culture-Work-Health Model

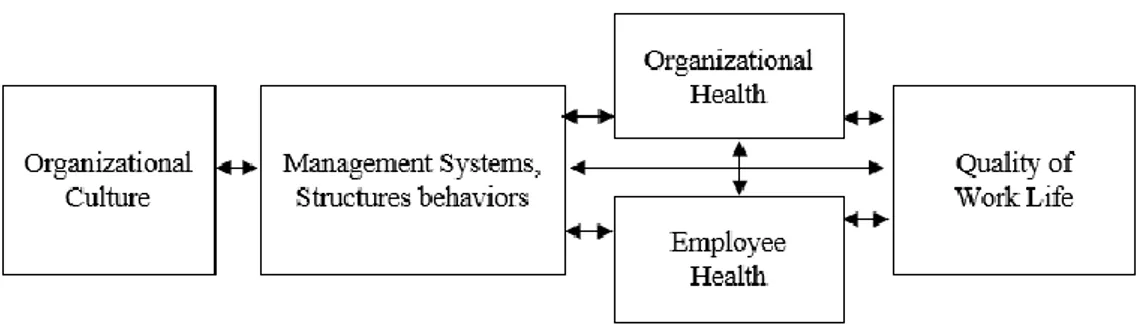

The Culture-Work-Health Model (CWHM) was first developed by Peterson & Wilson (1998). This model provides the theoretical framework for studying the role of organizational culture in the etiology of work-related stress. The key variables in this model are organizational culture, structure and behavior management systems, organizational health, employee health, and quality of work life. Within the framework of cultural discourse, work-related stress is a subject of as much business and management interest as health issues. The CWHM provides the theoretical basis for finding novel approaches to addressing work-related stress issues in work environments. As shown in Figure 1, this model recognizes organizational culture as the most important contributor of work-related stress and identifies other cultural factors that determine personal and organizational health.

Organizational culture includes the notions of human nature, human relationships, and assumptions and beliefs about the nature of time and space. It refers to a set of norms, values, beliefs, and attitudes shared by organization members, which shape the organization’s goals and actions (Peterson & Wilson, 2002). Organizational culture drives how organization members interact, act, and communicate and in the process helps form organizational structure.

Organizational culture affects the organization’s management systems, of which there are two types: structural and behavioral. Structural management systems include organizational policies, regulations, profits, rewards, organizational structures, job design, and work environment. Behavioral management systems include communication styles, i.e. how employees communicate in the context of their departments and work areas, management styles, decision-making styles, the degree of control and autonomy given to employees, and assessment and feedback(Peterson & Wilson, 2002).Supervisors’ leadership conveys the organization’s culture, values, and beliefs. Their behavior and communication methods affect the interaction among organization members and organizational health (Peterson & Wilson, 2002).

Organizational health refers to a state of well-being throughout the organization and can be measured by the organization’s productivity, performance, quality, competitiveness, and benefits. Employee health is measured by employee conditions such as physical and mental illness, frequent absenteeism, and fatigue (Peterson & Wilson, 2002). Fear of punitive actions against errors forces employees to subdue their motivation

to try something new or contribute to their organization (Peterson & Wilson, 2002). In addition, Peterson & Wilson (2002) found that negative emotions harbored by employees in response to unhealthy work environments eventually lead to self-destruction, which in turn negatively influences organizational health and results in a loss of organizational productivity. Therefore, minimizing the self-destructive aspects of the organization’s culture is crucial in this regard. This model emphasizes the role of organizational culture in keeping the balance between employee health and organizational health, which are both equally important and must be considered in relation to each other. In conclusion, the CHWM provides the groundwork in this study for assessing the balance between employee health and organizational health and understanding how these variables affect the quality of work life of nurses.

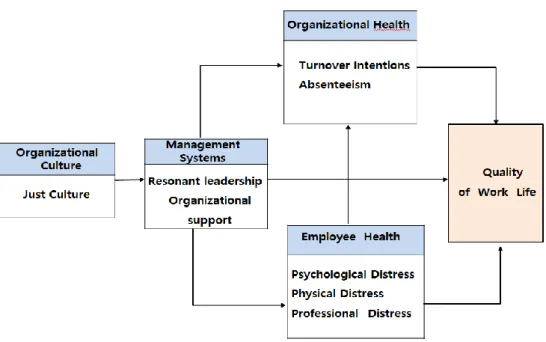

B. Conceptual Framework of this study

This study was based on the CWHM as described in Figure 2 under the assumption that the quality of work life of nurses is determined by organizational culture, management systems, organizational health, and employee health. The main constructs of this study include just culture, resonant leadership, organizational support, organizational health, employee health, and quality of work life. In this study, it was assumed that just culture affects resonant leadership and organizational support, resonant leadership and organizational support affect employee health and organizational health, and employee health and organizational health affect quality of work life.

Ⅳ. Methods

A. Design

This study aims to identify influence factors of the work-related quality of life of nurses who have experienced patient safety incidents by incorporating a mixed methods research design approach, conducting both quantitative and qualitative studies. In specific, this study uses the convergent parallel design method which produces an integrated perspective by comparing and correlating the results from quantitative and qualitative studies (Creswell & Clark, 2011).

In a convergent parallel design study, data from both quantitative study and qualitative study are collected and integrated into a unified result. In this study, work-related quality of life of nurses after patient safety incidents was assessed in a quantitative study based on variables such as employee health, organizational health, organizational support, and resonant leadership. At the same time, the participants’ experiences after patient safety incidents were closely examined through in-depth interviews in a qualitative study. comparative analyses of the results from the quantitative and qualitative studies were integrated (Figure3).

Figure3. Convergent Parallel Mixed methods Design (Creswell,2011)

B. Quantitative Study

1. Participants

The Participants was 622 nurses who experienced patient safety incidents within the last 1 year were recruited from general or tertiary general hospitals nationwide

1.1 Sample size estimation

Following the study finding that the minimum required sample size for each independent variable in a multiple regression analysis is 10 participants (Lee et al., 2006), the minimum sample size for the 27 predictors in this study was calculated to be 270 participants.

1.2 Sampling Method

In this study, data collection was conducted through an online panel survey. Nurscape (www.nurcape.net), an exclusive online community for nurses, provided access to 20,000 nurses currently working at general hospitals and tertiary general hospitals nationwide. Considering the 14-30% chance among health care providers of experiencing patient safety incidents (Scott et al., 2009), 2,807 participants were expected to meet the conditions of this study.

The sample size of the study was defined to include all 20,000 participants, considering the following three conditions: 1) prior studies conducted on the online survey platform SurveyMonkey have reported a response rate of 23.6% (An & Kim, 2013) high bias rates due to unreliable responses have been reported among online surveys. 3) some participants who experienced patient safety incidents may have reservations about sharing their personal experiences.

During data collection, the online URL link to the survey was sent to 20,000 target participants through E-mails and mobile messages. Among them, 1,222 accessed the link to the survey (16.4% response rate). 332 (3.7%) were eliminated due to incompletion, 214 (4.2%) did not meet the inclusion criteria, and data were collected from the remaining 676 participants. 54 outliers, inaccurate data and missing data were eliminated before 622 were finally examined (Figure 4).

2. Measurement Tools

2.1 Measure

2.1.1 Socio-Demographic Variables

Socio-demographic variables considered in this study were gender, age, marital status, education level, hospital work experience, work unit, turnover experience, and hospital type.

2.1.2 Variable related to Patient Safety Incident

Patient safety incident related variables examined in this study included types of patient safety incidents - medication errors, falls/slips, suicides or suicide attempts or self-harm, extravasation or phlebitis, examination-related incidents, facility or instrument related incidents, and accidental catheter removal , transfusion related incidents - severity of incidents, and duration of physical and psychological distress experienced after patient safety incidents.

2.1.3 Just Culture

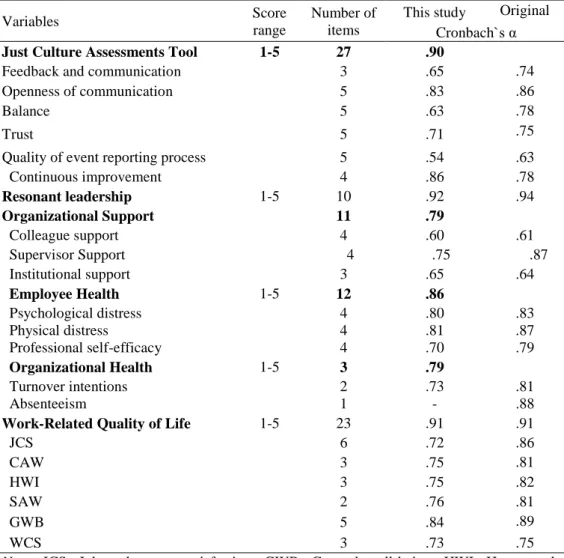

The Just Culture Assessment Tool (JCAT)developed by Petschonek et al. (2013) was used to measure just culture. After receiving the approval of its original developer, the tool was translated into Korean and reviewed for reliability and validity before use. The sub-variables of each item consisted of 27 items including 3items on feedback and communication, 5 items on openness of communication, 5 items on balance, 5items on

trust, 5items on quality of reporting process, and 4items on continuous improvement. Every item was scored on a five-point Likert scale ranging from ‘Strongly disagree’ with 1 point to ‘Strongly agree’ with 5 points. A high score indicates a high degree of just culture in the responder’s organization. Reverse-scored items were included in the survey. In the original tool development, Cronbach’s alpha reliability for the sub-variables were .74 for feedback and

communication, .86 for openness of communication, .78

for balance, .63 for quality of event reporting process, .78 for continuous

improvement, and .75 for trust. In this study, Cronbach’s alpha reliability were .65

for feedback and communication .83 for openness of

communication, .63 for balance, .54 for quality of event reporting process, .86 for continuous improvement, and .71 for trust.2.1.4 Resonant Leadership

Resonant leadership was measured by the Resonant Leadership Scale developed by Cummings et al. (2013) including 10 items. All items were scored on a five-point Likert scale ranging from ‘Strongly disagree’ with 1 point to ‘Strongly agree’ with 5 points. A high score indicates a high level of resonant leadership. Cronbach’s alpha reliability in the original study was .94 and .92 in this study.

2.1.5 Organizational Support

Support Tool (SVEST) developed by Jonathan et al (2014) including 4items on colleague support, 4items on supervisor support, 3 items on institutional support. All items were scored on a five-point Likert scale ranging from ‘Strongly disagree’ with 1 point to ‘Strongly agree’ with 5 points, and reverse-scored items were included. A high score indicates that a high level of organizational support is perceived by the responder. All items were compared on an average-score basis. Cronbach’s alpha reliability presented in Jonathan et al. were .61 for colleague support, .88 for supervisor support, .64 for institutional support. In this study, Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for organizational support was .60 -.75.

2.1.6 Employee Health

Employee health was measured by 12 items from the SVEST developed by Jonathan et al (2014) including 4items on psychological distress, 4 items on physical distress, 4items on professional self-efficacy. All items were scored on a five-point Likert scale ranging from ‘Strongly disagree’ with 1 point to ‘Strongly agree’ with 5 points, and reverse-scored items were included. A high score indicates a low level of employee health. Each item was compared on an average-score basis. Cronbach’s alpha reliability presented in Jonathan et al. (2014) were .83 for psychological distress, .87 for physical distress, and .79 for professional self-efficacy. In this study, Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for employee health was .70-.80.

2.1.7 Organizational Health

Organizational health was measured by 2 items on turnover intention and 1 on absenteeism from the Second Victim Experience and Support Tool (SVEST) developed by Jonathan et al (2014) . Every item was scored on a five-point Likert scale ranging from ‘Strongly disagree’ with 1 point to ‘Strongly agree’ with 5 points. Reverse-scored items were included. A high score indicates a low level of organizational health in the organization. The items were compared on an average-score basis. Cronbach’s alpha reliability presented in Jonathan et al (2014) were .81 for turnover intention and .88 for absenteeism. In this study, Cronbach’s alpha for organizational health measured by 2 turnover intention items and 1 absenteeism item was .80.

2.1.8 Quality of Work Life

Quality of work life was measured by the Work-Related Quality of Life (WRQoL) Scale developed by Easton and Van Lar (2013). The use of the tool was approved by its original developer before translating it into Korean. The sub-variables of each item consisted of 23 items including 6items on job and career satisfaction (JCS), 5items on general well-being (GWB), 2 items on stress at work (SAW), 3 items on control at work (CAW), 3 items on home-work interface (HWI), and 3items on working conditions (WCS), and overall satisfaction item1 .All items were scored on a five-point Likert scale ranging from ‘Strongly disagree’ with 1 point to ‘Strongly agree’ with 5 points, and a high average score indicated a high quality of work life. Cronbach’s alpha

reliability presented in Easton and Van Larr (2013) were .86 for JCS, .81 for CAW, .75 for HWI, .81 for SAW, .84 for GWB, and .75 for WCS. In this study, Cronbach’s alpha coefficients were .91 for quality of work life and .73-.84 for sub-variables (Table 4).

2.2 Translation and Development of Tools

2.2.1 Translation

Appropriate tools were selected based on findings from the Previous studies. For assessing just culture, the Just Culture Assessment Tool (JCAT) developed in Petschonek et al. (2013) was used. For assessing resonant leadership, the Resonant Leadership Scale developed in Cummings et al. (2013) was used. For assessing work-related quality of life, the Work-Related Quality of Life Scale developed in Easton and Van Lar. (2013) was used. The permission to use the tools was approved in writing by its original author. For accurate results, each tool was translated jointly by a committee of three individuals—the researcher, a nursing professor with proficiency in English and Korean, and a nurse with proficiency in English. First drafts of translated tools were reviewed for cultural relevance with the help of two nursing professors who are bilingual in English and Korean. In the JCAT, for example, “event” was modified as “patient safety incident,” “management” as “our hospital’s management,” and “follow up team”as “patient safety team.” Also, “tattle” was modified as “assign blame” and “my supervisor” as“the supervisor in my work unit.” In translating the Resonant Leadership Scale, the expression “the leader in my clinical program or unit” was modified as “the supervisor in my work unit” and “feedback” as

“pay attention to my updates and give feedback.” In the WRQoL, “work” was modified as “workplace” and “facility” as “work environment.” Also, “new skill” was modified as “new work experience.”

2.2.2 Content Validity Assessment

1) Expert panel review

Content validity of the translated JCAT, Resonant Leadership Scale, and WRQoL was assessed by an expert group to determine whether each of them is suitable for assessment of just culture, resonant leadership, and work-related quality of life (Appendix. Expert Assessment Survey).

The expert group assessing the Resonant Leadership and WRQoL consisted of 7 experts including two doctoral degree head nurses in clinical practice, two nurses pursuing a doctoral degree, and three nursing professors. The expert group assessing the JCAT consisted of 9 individuals including two doctors, a QI team leader with over ten years of patient safety experience, a patient safety expert pursing a doctoral degree, three nursing professors, and two doctoral degree head nurses working in hospitals.

The Item-level Content Validity Index (I-CVI) and the Scale-level Content Validity Index (S-CVI) were used in assessing the content validity of the tools. The validity of each tool was evaluated on a five-point scale - 1 point for “strongly disagree,” 2 points for “disagree,” 3 points for “neutral,” 4 points for “agree,” and 5 points for “strongly agree”. Suggestions for revision or addition of information in the survey were

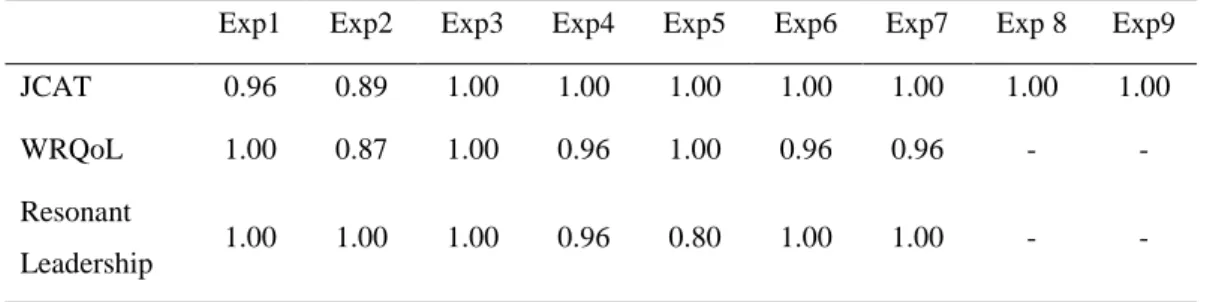

taken in writing. The survey was modified and finalized based on expert inputs. The I-CVI was determined by the ratio of experts who gave a score of 3 or 4. In this study, the I-CVI for the JCAT was 0.98, 0.97 for the WRQoL, and 0.96 for the Resonant Leadership Scale. The S-CVI was determined by the ratio of items that received a score of 3 or 4. In this study, the S-CVI for the JCAT was 0.98, 0.96 for the WRQoL, and 0.96 for the Resonant Leadership (Table 2).

Among the WRQoL items, the fourth item “I feel well at the moment” received a score of 2 from 3 experts, and its average I-CVI was only 0.57. Following the expert opinion, the item was removed from the survey.

Table 2. Content Validity Index of the measurements

Exp1 Exp2 Exp3 Exp4 Exp5 Exp6 Exp7 Exp 8 Exp9 JCAT 0.96 0.89 1.00 1.00 1.00 1.00 1.00 1.00 1.00

WRQoL 1.00 0.87 1.00 0.96 1.00 0.96 0.96 - -

Resonant

Leadership 1.00 1.00 1.00 0.96 0.80 1.00 1.00 - - Mean I-CVI=JCAT 0.98 , WRQoL 0.97, Resonant Leadership 0.96

S-CVI/UA= JCAT 0.98 , WRQoL 0.96 , Resonant Leadership 0.96

JCAT, Just Culture Assessment Tool; WRQoL, Work-Related Quality of Life; I-CVI, item-level content validity index; S-CVI, scale-level content validity index, universal agreement calculation method

2) Cognitive Interviewing

Cognitive interviews with nurses were conducted to closely examine the adequacy of each tool by evaluating whether the tool developer’s purpose was sufficiently addressed in the way participants understood the translated items. One-to-one, in-depth interviews with the participants were conducted based on their answers to the survey to examine whether they understood each item in the way that the researcher had intended, whether they were confused or uncertain about the its meaning, and whether the item was phrased in a way that allowed them to answer without difficulties. In this stage, every word and sentence included in the survey was reviewed based on findings from the cognitive interviews (Jang, 2014). Five nurses each participated in an interview with the surveyor and the researcher and examined the items one-by-one while paying attention to the terms and semantics. As a result of the cognitive interviews, several modifications were made in the JCAT item “the supervisors respect employees’ suggestions”— “the supervisors” was modified as “the supervisor in my work unit” and “suggestions” as “suggestions and ideas” to reflect the comments that the original word might imply only formal communications. Also, “uses a balanced and fair system for appraising employees” was modified as “follows fair procedures in appraising employees” based on the input that the original phrase might be obscure to nurses. “I am uncomfortable with others entering reports about events in which I was involved” was removed from the survey after reviewing reliability to reflect the comment that the item had little relevance in the context of the Korean work environment. In the Resonant Leadership Scale,

“Looks for feedback even when it is difficult to hear” was commented as obscure and modified as “The supervisor in my work unit pays attention to my updates even when it is difficult to hear and gives feedback.” In addition, “Acts on values even if it is at a personal cost” was commented as obscure, so it was modified as “The supervisor in my work unit takes action for the good of the unit (or team) even if it has personal consequences.” The nurses who assessed the WRQoL items in cognitive interviews did not report any difficulty in understanding and answering the items, and it was concluded that that they were appropriately worded.

3) Pilot- study

The survey used in the pilot-study included the following: JCAT 27 items, 10 Resonant Leadership items, 23 WRQoL items, grammar and context of which were all reviewed by scholars of Korean literature after modifications were made based on expert validity assessment and cognitive interviews, and 28 SVEST (Second Victim Experience and Support Tool) items that assess physical and psychological distress and organizational support after patient safety incidents, and items regarding general characteristics. The participants of the pilot-study were 30 nurses working in general hospitals who experienced patient safety incidents within the last one year.

2.2.3 Verification of the Tool Reliability

1) Test–retest reliability

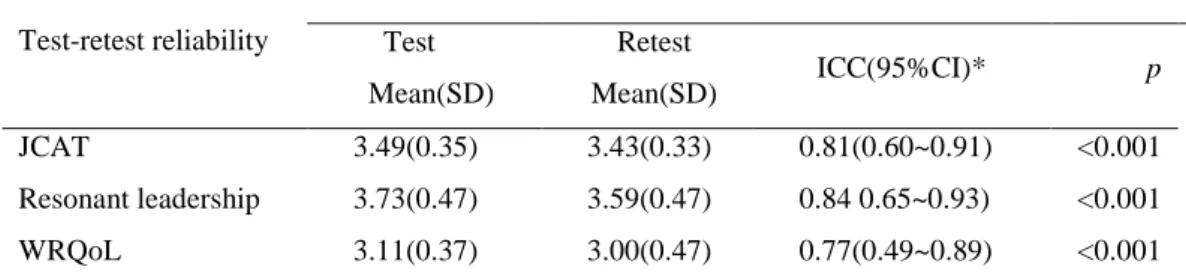

Test-retest reliability was measured to assess consistency of each tool. The 30 participants of the pre-study were asked to take the survey again after 2 weeks, and 28 of them agreed. Data collection for the pre- study was conducted from February 22 to March 8, 2020 Using the criteria of test-retest correlation coefficient is higher than .70 (DeVon et al, 2007). The intra-class correlation coefficient for the JCAT was .81 (95% CI 0.60-0.91), 0.84 (95% CI 0.65-0.93) for the Resonant Leadership Scale, and 0.77 (95% CI 0.49-0.89) for the WRQoL. In conclusion, all three tools were proven to be consistent (Table 3).

Table 3. Test-retest reliability of the measurements

(N=28) Test-retest reliability

Intra-class correlation coefficients Test Mean(SD) Retest Mean(SD) ICC(95%CI)* p JCAT 3.49(0.35) 3.43(0.33) 0.81(0.60~0.91) <0.001 Resonant leadership 3.73(0.47) 3.59(0.47) 0.84 0.65~0.93) <0.001 WRQoL 3.11(0.37) 3.00(0.47) 0.77(0.49~0.89) <0.001

JCAT, Just Culture Assessment Tool; WRQoL, Work-Related Quality of Life; CI, confidence interval.