저작자표시-비영리-변경금지 2.0 대한민국 이용자는 아래의 조건을 따르는 경우에 한하여 자유롭게 l 이 저작물을 복제, 배포, 전송, 전시, 공연 및 방송할 수 있습니다. 다음과 같은 조건을 따라야 합니다: l 귀하는, 이 저작물의 재이용이나 배포의 경우, 이 저작물에 적용된 이용허락조건 을 명확하게 나타내어야 합니다. l 저작권자로부터 별도의 허가를 받으면 이러한 조건들은 적용되지 않습니다. 저작권법에 따른 이용자의 권리는 위의 내용에 의하여 영향을 받지 않습니다. 이것은 이용허락규약(Legal Code)을 이해하기 쉽게 요약한 것입니다. Disclaimer 저작자표시. 귀하는 원저작자를 표시하여야 합니다. 비영리. 귀하는 이 저작물을 영리 목적으로 이용할 수 없습니다. 변경금지. 귀하는 이 저작물을 개작, 변형 또는 가공할 수 없습니다.

Mast

er

'

sThesi

si

n Medi

calSci

ence

CT Eval

uat

i

on ofAcut

e

Abdomi

nalPai

n i

n Pat

i

ent

swi

t

h

Acut

eLeukemi

a

Aj

ou Uni

ver

si

t

y Gr

aduat

eSchool

Medi

ci

neMaj

or

CT Eval

uat

i

on ofAcut

e

Abdomi

nalPai

n i

n Pat

i

ent

swi

t

h

Acut

eLeukemi

a

J

aiKeun Ki

m,Advi

sor

Isubmi

tt

hi

st

hesi

sast

heMast

er

'

st

hesi

s

i

n Medi

calSci

ence.

August2014

Aj

ou Uni

ver

si

t

y Gr

aduat

eSchool

Medi

ci

neMaj

or

TheMast

er

'

st

hesi

sofTaeSun

Han i

n medi

calsci

encei

s

her

eby appr

oved.

Thesi

sDef

enseCommi

t

t

eePr

esi

dent

JaiKeun Ki

m Se

al

MemberJ

oon Seong Par

k Se

al

Member

JooSung Sun Se

al

Aj

ou Uni

ver

si

t

y Gr

aduat

eSchool

Abstract

Introduction: Many diseases causing abdominal symptoms can occur in patients with

leukemia such as neutropenic enterocolitis, leukemic infiltration of GI tract, and infectious enterocolitis. However, many imaging finding of such diseases can have overlapping findings. The purpose of this study was to evaluate clinical data and CT features of acute abdominal pain in patients with acute leukemia to find out the causes of acute abdominal pain in our institution. Also to find out any CT feature that can be used as a prognostic factor, we analyzed the CT findings seen in these patients and sought any correlation between each CT feature and mortality.

Material and Methods: This retrospective study was approved by our institutional

review board which waived the requirement to obtain informed consent. Between January 2008 and January 2013, 107 CT examinations were performed in 76 patients with acute leukemia. Presence of neutropenia and fever (mortality and were investigated. The patients were divided into two groups, patients with mortality within one month after CT examination were considered as mortality group (n=21) and those without mortality within one month were considered as non-mortality group (n=69). Two reviewers evaluated the images for bowel related changes, ancillary findings, and other organ related findings. Differences between the mortality group and the non-mortality group with regard to small bowel wall thickness and large bowel wall thickness were analyzed using independent t-test. Comparison of proportions was used to analyze differences of other clinical and CT findings between two groups.

Results: Numerous diagnoses were made to the enrolled patients complaining of

abdominal pain based on clinical and CT findings. The most common clinical diagnosis was “no evident cause of acute abdomen” (n=23, 25.56%).The second most common clinical diagnosis was infectious enterocolitis (n=13, 14.44%). Other

common diagnoses were neutropenic enterocolitis (n=12, 13.33%), acute pancreatitis (n=7, 7.78%), and ischemic enterocolitis (n=5, 5.56%). Presence of neutropenia and fever were not different between two groups. The mean small bowel wall thickness was significantly thicker in the mortality group than the non-mortality group

(p=0.0062). Mesenteric stranding was seen in 11 cases (52.38%) in the mortality group and 18 cases (26.09%) in the non-mortality group which showed statistical difference (p=0.0465). Small bowel thickness cut off value of 3 mm has sensitivity and specificity of 52.38% and 79.71% respectively to be included in the mortality group. With the presence of mesenteric stranding, sensitivity and specificity to be included in mortality group, was 52.38% and 73.91%.

Conclusion: In cases when exact diagnosis of a patient may not be properly

diagnosed using clinical and imaging studies, small bowel wall thickness can be measure and used as a prognostic factor that has high negative predictive value. This can provide clinicians relieving information in managing leukemic patients with abdominal pain if the patient does not have small bowel wall thickening. When a patient presents with bowel wall thickening, this information may give suggestions to clinicians in determining more intensive therapeutic approach.

Table of contents 1. List of Text

I. Introduction

‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧

1

II. Materials and Methods

‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧

2

A. Study Population

‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧

2

B. Multidetector CT‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧

3

C. Image Interpretation‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧

3

D. Statistical Analysis‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧

5

III. Results‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧

6

IV. Discussion‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧

8

A. Limitation‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧ 13

V. Conclusion‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧

14

2. List of Figures▶

Figure 1. A 53 year old female with AML who complained of acute abdominal pain and fever was clinically diagnosed as CMV enterocolitis.‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧

15

▶

Figure 2. A 14 year old male with AML who complained of acute abdominal pain especially at right lower quadrant was clinically diagnosed as neutropenic enterocolitis.‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧ 16

▶

Figure 3. A 57 year old female with AML who complained of acute abdominal pain, fever, and diarrhea was clinically diagnosed as neutropenic enterocolitis.‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧

17

3. List of Tables

▶

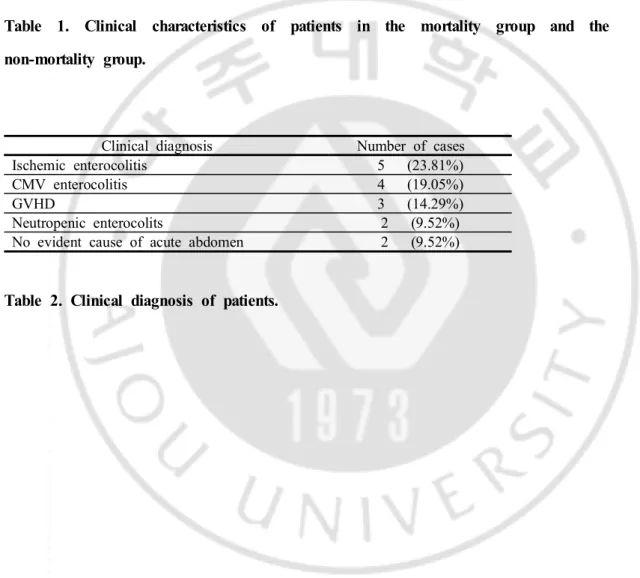

Table 1. Clinical characteristics of patients in the mortality group and the non-mortality group.‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧

18

▶

Table 2. Clinical diagnosis of patients.‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧ 18

▶

Table 3. Clinical diagnosis of patients in the Mortality group.‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧

19

▶

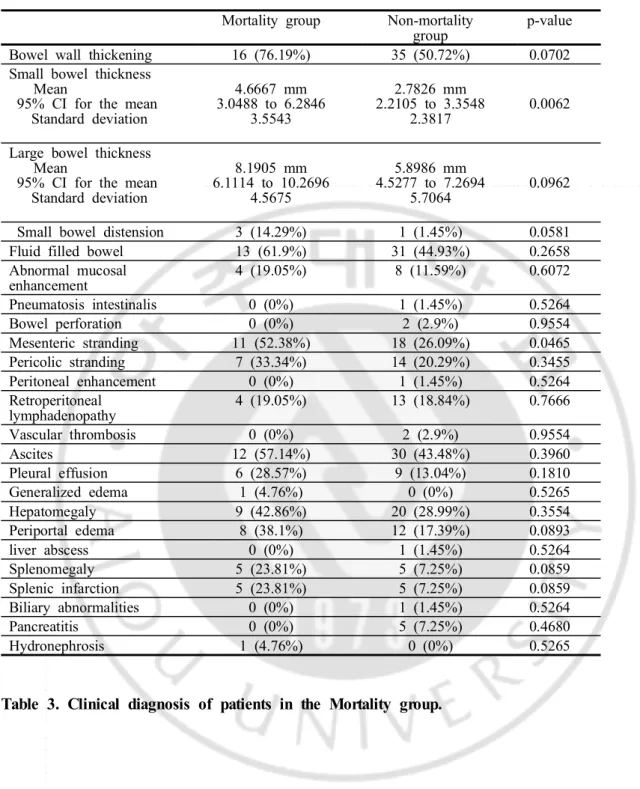

Table 4. CT findings of patients in the mortality group and the non-mortality group.‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧ 20

▶

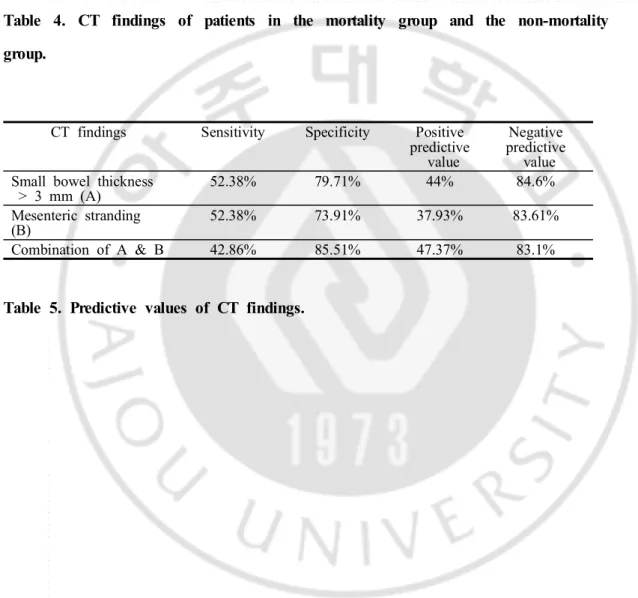

Table 5. Table 5. Predictive values of CT findings.‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧ 20

4. Bibliography‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧‧ 21

1

Introduction

Patients with hematological diseases may have some conditions that lead to acute abdominal complications such as opportunistic infection secondary to

neutropenia or following hematopoietic stem cell transplantation.1) Also,

gastrointestinal (GI) involvement of leukemia has been reported with autopsy reports ranging from 14.8 to 25% of gross GI involvement of leukemia.2)3) Many diseases

causing abdominal symptoms can occur in patients with leukemia such as neutropenic enterocolitis, leukemic infiltration of GI tract, and infectious

enterocolitis.4)5) Acute abdominal conditions are more common in acute rather than

chronic leukemia (5.3% and 2.6% respectively).6) In these hematologic patients,

clinical signs and laboratory findings can be non-specific and multidetector computed tomography (MDCT) can be helpful in providing image view of entire abdomen with excellent spatial resolution.7) However, many imaging finding of

several diseases such as neutropenic colitis, pseudomembranous colitis,

cytomegalovirus colitis, and graft-versus-host disease can have overlapping findings such as bowel wall thickening, ascites, and mesenteric stranding although some discriminatory findings are also known.8) Also there have not been many studies

1) C. Hordonneau, “Abdominal complications following neutropenia and haematopoietic stem celltransplantation:CT findings” Clin Radiol,Vol.68, pp.620-626,2013.

2)J.S.Cornes,“Leukaemic lesions of the gastrointestinaltract” J Clin Pathol,Vol.15,pp.305-313,1962.

3)J. C. Prolla, “The Gastrointestinal Lesions and Complications of the Leukemias”AnnInternMed,Vol61,pp.1084-1103,1964.

4)C.Hordonneau,op.cit.

5)E.C.Ebert,“Gastrointestinalmanifestationsofleukemia”J Gastroenterol Hepatol,Vol.27,pp.458-463,2012.

6)J.A.Hawkins,“Acuteabdominalconditionsinpatientswithleukemia”Am

JSurg,Vol.150,pp.739-742,1985.

7)C.Hordonneau,op.cit.

2

that showed prognostic value of many CT findings commonly seen in this group of patients.

The purpose of this study was to evaluate clinical data and CT features of acute abdominal pain in patients with acute leukemia to find out the causes of acute abdominal pain in our institution. Also to find out any CT feature that can be used as a prognostic factor, we analyzed the CT findings seen in these patients and sought any correlation between each CT feature and mortality.

Materials and Methods

Study Population

This retrospective study was approved by our institutional review board which waived the requirement to obtain informed consent. Between January 2008 and January 2013, 107 CT examinations were performed in 76 patients with acute leukemia; acute myeloid leukemia (AML) or acute lymphoid leukemia (ALL), who presented with acute abdominal pain at our institution. From 107 CT scans performed in these patients, 10 cases of repeated CT examinations within one month were excluded from analysis. Five CT examinations that were performed to follow up pancreatic pseudocyst in one patient were also excluded. One case with inadequate patient record and another case that did not contain contrast enhanced CT were also excluded. All 90 cases of abdominal CT examinations were performed due to acute abdominal pain; in 55 cases, patients also presented with fever. All abdominal CT examinations were carried out within 2 days of onset of abdominal pain.9) All patients were proven to have either AML or ALL by bone

9)J.Y.Byun,J“CT features ofsystemic lupus erythematosus in patients with acuteabdominalpain:emphasison ischemicboweldisease”Radiology,

3

marrow biopsy. There were 38 male and 38 female patients; age range, 4-77 years; mean age 52.09 years. Medical charts of each patient were retrospectively reviewed. Presence of grade 4 neutropenia (absolute neutrophil count<500/mm3) and fever, mortality and were investigated.10) The patients were divided into two groups,

patients with mortality within one month after CT examination were considered as mortality group (n=21) and those without mortality within one month were considered as non-mortality group (n=69).

Multidetector CT

CT examinations were performed with one of four commercially available 16-, 64-, or 128 channel multidetector CT (MDCT) scanners: Somatom Definition flash, Somatom Sensation 16 (Simens Medical Solutions, Erlangen, Germany), Briliance 16, Briliance 64 (Philips Healthcare, Cleveland, OH). Scans were obtained with 5 mm thick sections and 5 mm intervals. After taking unenhanced CT scan, contrast enhanced CT scan was obtained 90 seconds after the administration of 150 cc of nonionic contrast agent (Ioversol, ®; Pharmaceuticals, Dublin, Ireland)

intravenously at rate of 3 ml/sec using a power injector. For both unenhanced and enhanced CT, the scanning range was from xyphoid process to symphysis pubis.

Image Interpretation

CT scans were analyzed retrospectively by two experienced radiologists (J.K.L., T.S.H.). Blinded to clinical information, the reviewers evaluated the images

10)C.Cartoni,“Neutropenic enterocolitis in patients with acute leukemia: prognosticsignificanceofbowelwallthickening detectedbyultrasonography”

4

for bowel related changes (presence of bowel wall thickening, bowel distension, fluid filled bowels, abnormal mucosal enhancement, pneumatosis intestinalis, and bowel perforation), ancillary findings (presence of mesenteric stranding, pericolic stranding, peritoneal enhancement, retroperitoneal lymphadenopathy, vascular

thrombosis, ascites, pleural effusion, and generalized edema), and other organ related findings (presence of hepatomegaly, periportal edema, liver abscess, splenomegaly, splenic infarction, biliary abnormalities, pancreatitis, and hydronephrosis).11)12) (Table

4)

Bowel wall thickening was diagnosed if a small bowel wall was at least 3 mm thick13) and if a large bowel wall was at least 5 mm thick in areas with

adequately distended bowel.14) Presence of bowel distension was diagnosed if the

distended bowel had diameter of more than 2.5 mm in small bowels and 8 mm in large bowels.15) Abnormal mucosal enhancement was defined as hyperenhancement

of bowel mucosa.16) In the case of ascites, small amount of pelvic fluid seen in

premenopausal women was not considered positive for ascites. Hepatomegaly was defined as craniocaudal dimension greater than 15 cm in midclavicular line.17)

Splenomegaly was defined as craniocaudal span greater than 14 cm. Biliary

11)J.Y.Byun,op.citp.2

12)A.Shimoni,“CT in the clinical and prognostic evaluation of acute graft-vs-hostdiseaseofthegastrointestinaltract”BrJ Radiol,Vol.85,pp. e416-423,2012.

13)J.K.Fisher,“Abnormalcolonicwallthickening oncomputedtomography” JComputAssistTomogr,Vol.7,pp.90-97,1983.

14)C.F.Dietrich,“Sonographic signs ofneutropenic enterocolitis”World J Gastroenterol,Vol.12,pp.1397-1402,2006.

15)A.Shimoni,op.citp.4

16)E.C.Benya,“Abdominalcomplicationsafterbonemarrow transplantation in children:sonographic and CT findings” Am J Roentgenol,Vol.161,pp. 1023-1027,1993.

17) H. K. Ha, “Differentiation of simple and strangulated small-bowel obstructions: usefulness of known CT criteria” Radiology,Vol. 204,pp. 507-512,1997.

5

abnormalities were diagnosed when there was any stenosis or obstruction in biliary tree causing bile duct dilatation. In the presence of bowel wall thickening, bowel wall thickness was measured at two portions of bowels that seemed to have the thickest wall and an average of these values was calculated.

Based on clinical symptoms, laboratory data, and CT findings, clinical diagnoses were made for each case of CT examination. When clinical features and CT images showed no imaging findings to explain acute abdominal symptoms of a patient, it was categorized as “no evident cause of acute abdomen”.Neutropenic enterocolitis was diagnosed when following criteria was included: presence of neutropenia, fever, acute abdominal pain, and bowel wall thickening.18)19)20) GVHD was confirmed by

GI biopsies. CMV infection was confirmed by serum test of CMV antigenemia or PCR and PMC were confirmed by positive serum clostridium difficile toxin A.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using MedCalc software (MedCalc, Mariakerke, Belgium). Differences between mortality group and non-mortality group with regard to small bowel wall thickness and large bowel wall thickness were analyzed using independent t-test.

18)A.F.Cardona Zorrilla,“Systematic review ofcase reports concerning adultssuffering from neutropenicenterocolitis”Clin TranslOncol,Vol.8,pp 31-38,2006.

19)D.Mullassery,“Diagnosis,incidence,and outcomesofsuspected typhlitis in oncology patients--experiencein atertiary pediatricsurgicalcenterin the UnitedKingdom”JPediatrSurg,Vol.44pp.381-385,2009.

20)J.H.Lee,“Gastrointestinalcomplicationsfollowinghematopoieticstem cell transplantationinchildren”KoreanJRadiol,Vol.9,pp.449-457,2008.

6

Comparison of proportions was used to analyze differences of other clinical and CT findings between two groups. P < .05 was considered significant.

Results

Total of seventy-three patients were included and fifty-one patients (69.86%) had acute myeloid leukemia and twenty-two patients (30.14%) had acute lymphoid leukemia. In 55 cases (75.34%), patients also presented with fever along with acute abdominal pain. Abdominal CT was performed up to three times in some patients with total of 90 scanned CT examinations.

Numerous diagnoses were made to the included patients complaining of abdominal pain based on clinical and CT findings. The most common clinical diagnosis was “no evident cause of acute abdomen” (n=23, 25.56%). The second most common clinical diagnosis was infectious enterocolitis (n=13, 14.44%) including 6 cases of cytomegalovirus (CMV) enterocolitis and 1 case of pseudomembranous colits (PMC). Other diagnoses, in order of frequency, were neutropenic enterocolitis (n=12, 13.33%), acute pancreatitis (n=7, 7.78%), ischemic enterocolitis (n=5, 5.56%), splenic infarction (n=4, 4.44%), paralytic ileus (n=4, 4.44%), GVHD (n=3, 3.33%), acute cholecystitis (n=3, 3.33%), acute appendicitis (n=2, 2.22%), and granulocytic sarcoma (n=2, 2.22%). (Table 2)

In the mortality group mean age was 45.86 and in the non-mortality group 39.77. There was no significant difference between two groups. Presence of neutropenia was not different between two groups; mortality group (n=12, 57.14%) and non-mortality group (n=31, 44.92%). Presence of fever also did not show significance between two groups; mortality (n=15, 71.43%) and non-mortality group (n=40, 57.97%). (Table 1) In the mortality group, ischemic colitis was the most

7

common clinical diagnosis (n=5, 23.81%) followed by CMV enterocolitis (n=4, 19.05%), GVHD (n=3, 14.29%), neutropenic enterocolitis (n=2, 9.52%), and “no evident cause of acute abdomen” (n=2, 9.52%). (Table 3)

In the mortality group, mean small bowel wall thickness was 4.67 mm (SD 3.55; range, 1 to 12); mean small bowel wall thickness was 2.78 mm (SD 2.38; range, 1 to 12) in the non-mortality group. The mean small bowel wall thickness was significantly thicker in the mortality group than the non-mortality group (p=0.0062). Mesenteric stranding was seen in 11 cases (52.38%) in the mortality group and 18 cases (26.09%) in the non-mortality group which showed statistical difference (p=0.0465). (Table 4)

ROC curve analysis showed that small bowel thickeness cut off value of 3 mm has sensitivity and specificity of 52.38% and 79.71% respectively to be included in the mortality group. With the presence of mesenteric stranding, sensitivity and specificity to be included in the mortality group was 52.38% and 73.91% respectively. Combination of small bowel wall thickening and mesenteric stranding showed sensitivity of 42.86% and specificity of 85.51% to be included in the mortality group. (Table 5)

Presence of bowel wall thickening was seen in 16 cases (73.19%) of the mortality group and 35 cases (50.72%) of the non-mortality group (p=0.0702). In the mortality group, mean large bowel wall thickness was 8.19 mm (SD 4.57; range, 2 to 17); mean large bowel wall thickness was 5.90 mm (SD 5.71; range, 1 to 33) in the non-mortality group (p=0.0962). Presence of small bowel distension was seen in 3 cases (14.29%) of the mortality group and 1 cases (1.45%) of the non-mortality group (p=0.0581). These values showed some differences, however statistical significance was not seen. Other CT findings showed no significant difference between two groups. (Table 4)

8

Discussion

There are numerous conditions that can cause acute abdominal pain in patients with acute leukemia, common causes including neutropenic enterocolitis, leukemic infiltration of GI tract, infectious enterocolitis, and acute GVHD.21)22)

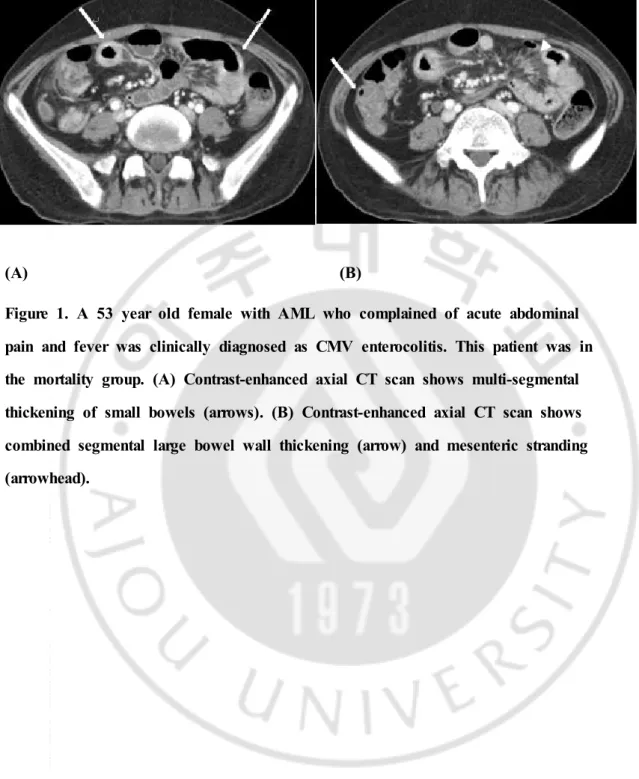

Our study showed that leukemic patients with acute abdominal pain most commonly had negative findings in laboratory and CT examination (n=22).The second most common clinical diagnosis was infectious enterocolitis (n=13). Infectious colitis included CMV enterocolitis (n=6) and PMC (n=1). Of six CMV enterocolitis cases four cases had mortality. CMV is leading most common cause of gastrointestinal infectious complications during early post-transplatation period.23) CT findings are

similar to that of neutropenic enterocolitis including ascending colon thickening, small bowel involvement, fat stranding, and ascites.24)25) (Figure 1) Common CT

finding of PMC is marked eccentric or circumferential wall thickening with diffuse colonic involvement.26)

Neutropenic enterocolitis was the third most common clinical diagnosis in our institution. The incidence of neutropenic enterocolitis in our study group was 6.38% between 2008 and 2013 among 188 patients with acute leukemia, which was similar to previous reports with pooled incidence rate of 5.6% for patients with acute leukemias treated with chemotherapy.27)28) Neutropenic enterocolitis is reported to

21)C.Hordonneau,op.cit.p.1

22)E.C.Ebert,op.cit.p.1

23) M. Schmit, “CT of gastrointestinal complications associated with hematopoietic stem celltransplantation” Am J Roentgenol,Vol.190,pp. 712-719,2008.

24)

i

bi

dp.8

25)S.P.Spencer,“The acute abdomen in the immune compromised host”

CancerImaging,Vol.8,pp.93-101,2008.

26)K. M. Horton, “CT evaluation of the colon: inflammatory disease”

9

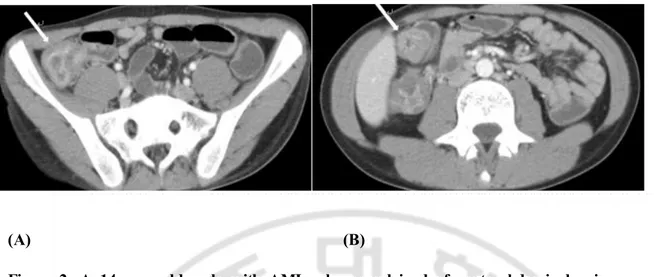

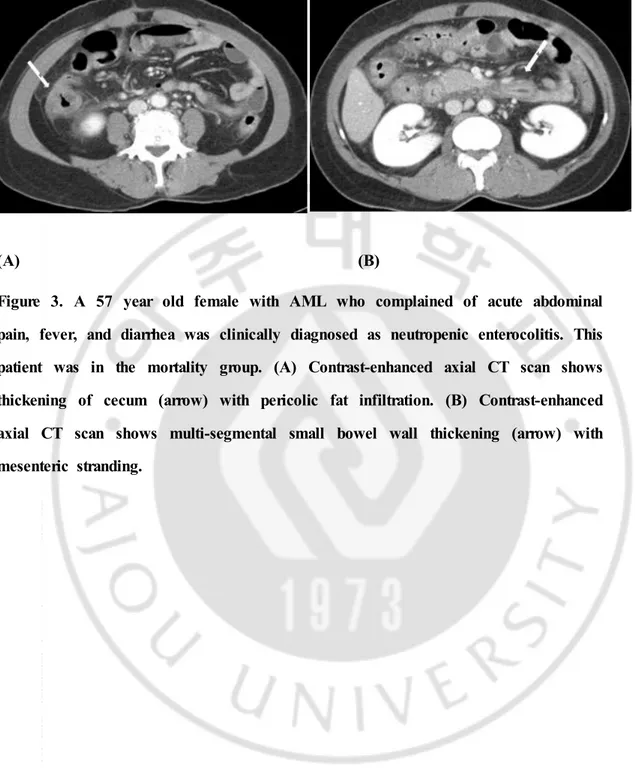

occur up to 32.5% during chemotherapy.29) CT findings that can be seen

inneutropenic enterocolitis are non-specific ileus, diffuse bowel wall thickening, mesenteric stranding, extraluminal collections, pericecal inflammation, phlegmon, or pneumatosis intestinalis.30)31) (Figure 2, 3) The mortality rate in our study was

16.67 %. Mortality in neutropenic enterocolitis patients is reported from 2.2 to 48 %.32)33)

Acute pancreatitis was seen in 7 cases in our study. Pancreatitis is reported to be rare although leukemic infiltration of pancreas is commonly seen in autopsy.34)

Previous reports show that acute pancreatitis can occur in patients using L-aparaginase during chemotherapy even 10 weeks after stopping therapy.35)

Ischemic enterocolitis occurred in five cases and all had mortality within one month. Bowel wall thickening is most common but not specific sign of bowel ischemia.36)37) In study by Jones et al, 14 (28%) patients with acute leukemia who

presented with acute abdominal catastrophy had administration of cytarabine in 13

27)C.Cartoni,op.citp.3

28)A.F.CardonaZorrilla,op.citp.5

29)D.Mullassery,op.citp.5

30)S.A.Teefey,“Sonographic diagnosis of neutropenic typhlitis” Am J

Roentgenol,Vol.149,pp.731-733,1987.

31)M. P. Frick, “Computed tomography of neutropenic colitis” Am J

Roentgenol,Vol.143,pp.763-765,1984.

32)M.B.McCarville,“Typhlitis in childhood cancer” Cancer,Vol.104,pp. 380-387,2005.

33) E. Takaoka, “Neutropenic colitis during standard dose combination chemotherapywithnedaplatinandirinotecanfortesticularcancer”JpnJClin Oncol,Vol.36,pp.60-63,2006.

34)F.Kuffer,“Surgicalcomplicationsin children undergoing cancertherapy”

AnnSurg,Vol.167,pp.215-219,1968.

35)R.M.Weetman,“Latentonsetofclinicalpancreatitisinchildrenreceiving L-asparaginasetherapy”Cancer,Vol.34,pp.780-785,1974.

36)W.Wiesner,“CT of acute bowelischemia” Radiology,Vol.226,pp. 635-650,2003.

37)B.J.Bartnicke,“CT appearance of intestinalischemia and intramural hemorrhage”RadiolClinNorthAm,Vol.32,pp.845-860,1994.

10

of the 14 patients and mortality was seen in all but one patient that were more frequently related with bowel necrosis.38)

GVHD occurred in three cases and all had mortality within one month. Acute GVHD reports up to 30-75% of gastrointestinal involvement in patients undergoing stem cell transplantation.39) Long term survival is reported to be variable, ranging

from 5-80% depending on disease grade and steroid response.40) Common CT

finding is abnormal mucosal enhancement of entire gastrointestinal tract especially on the small bowel. Bowel wall thickening greater than 7 mm, fluid filled and dilatated bowel loops, mesenteric stranding and lymphadenopathies are uncommon .41)42)

Acute cholecystitis was seen in 3 cases in our study. Patients with acute leukemia may present with cholecystitis-like symptoms and gallbladder wall infiltration of myeloid cells can rarely cause cholecystitis.43)44) Splenic infarction was seen in 4

cases. Splenic infarction is reported in 16% of patients who die of leukemia which occur more commonly in those with CML and acute leukemia.45) Acute appendicitis

38)G.T.Jones,“Gastrointestinalnecrosis in acute leukemia:a complication ofinductiontherapy”CancerInvest,Vol.1,pp.315-320,1983.

39) S. Y. Mahgerefteh, “Radiologic imaging and intervention for gastrointestinal and hepatic complications of hematopoietic stem cell transplantation”Radiology,Vol.258,pp.660-671,2011.

40)M.Schmit,op.citp.8

41)ibidp.10

42) I. D. Kirkpatrick, “Gastrointestinal complications in the neutropenic patient:characterization and differentiation with abdominalCT” Radiology,

Vol.226,pp.668-674,2003.

43) C. A. Dasanu, “Chronic lymphocytic leukemia presenting with cholecystitis-likesymptomsandgallbladderwallinvasion”SouthMedJ,Vol. 103,pp.482-484,2010.

44)S.H.Bloom,“Cholecystitis as the presenting manifestation of acute myeloid leukemia:reportofa case” Am J Hematol,Vol.70,pp.254-256, 2002.

45)M.Barcos,“Anautopsy study of1206acuteandchronicleukemias(1958 to1982)”Cancer,Vol.60,pp.827-837,1987.

11

was seen in 2 cases. Acute appendicitis found in 27% of patients with acute leukemia at autopsy presents similar symptoms as neutropenic enterocolitis.46)

Clinical features such as age, neutropenia, and fever were not significantly different between mortality and non-mortality group. Previous studies showed similar results that mortality is not related to the duration or level of neutropenia.47) Study by E

Altinelet al, showed that rise of neutrophil count and time to recover neutropenia are prognostic factors of neutropenic enterocolitis.48)

Differential diagnosis of each disease that cause abdominal symptom is sometimes difficult even with the availability of CT scans due to overlapping of imaging features and clinicians may need correlation of laboratory examinations. However, there are few studies that evaluated CT features of leukemia patient with abdominal pain to use as prognostic factor. One study that evaluated large bowel wall thickness in typhlitis patients showed that bowel wall thickness of more than 10 mm can be used as prognostic value to predict mortality.49)50) This study however

was limited to childhood patients with typhlitis and bowel wall thickness was measured using ultrasonography. Our study sought to find out whether any of the CT features can be used as prognostic factors in leukemia patients with acute abdominal pain.

Small bowel wall thickness was significantly higher in the mortality group

46)W.Johnson,“Acute appendicitis in childhood leukemia”J Pediatr,Vol. 67,pp.595-599,1965.

47)A.F.CardonaZorrilla,op.citp.5

48)E.Altinel,“Typhlitisin acutechildhoodleukemia”Med PrincPract,Vol. 21,pp.36-39,2012.

49)E.C.Ebert,op.citp.1

12

compared to the non-mortality group. Small bowel wall thickness thicker than 3 mm showed sensitivity of 52.38% and specificity of 79.71% in differentiating two groups. Small bowel wall thickness can be used as prognostic factor of mortality with high negative predictive value. These results suggest that small bowel wall thickness of less than 3 mm, which is normal bowel wall, can predict better clinical prognosis. (Figure 2)

Presence of bowel wall thickening that includes either thickening of small or large bowel or both showed some difference between two groups however no clinical significance was seen. Also large bowel wall thickening was thicker in the mortality group without statistical significance.

In the mortality group 17 cases showed bowel wall thickening. From this group, 13 cases showed small bowel wall thickening and 10 (76.92%) of these cases also showed any portion of large bowel wall thickening simultaneously, 8 of them being involvement of entire colon and small bowels. This suggests that many of the cases with small bowel wall thickening in the mortality group showed panenterocolitis. Larger area of bowel involvement may suggest more extensive disease and this may explain the increase in mortality in patients with small bowel wall thickening. (Figure 1, 3) Study by A Shimoni et al, showed that diffuse small-bowel disease and any colonic involvement were related with severe clinical GHVD and furthermore, diffuse small-bowel disease was associated with poor prognosis.51)

However interpretation of prognosis requires caution and larger prospective studies are needed to confirm that CT findings may give information of poorer prognosis.

Mesenteric stranding was seen significantly more in the mortality group. However, mesenteric standing is an ancillary finding seen in many diseases involving the small bowel and this finding is probably related with small bowel wall thickening.

13

Presence of mesenteric stranding alone shows similarly high specificity and negative predictive value. (Figure 1)

Combination of small bowel thickening and mesenteric stranding slightly elevates specificity with similar negative predictive value, however sensitivity is slightly decreased.

Many of these patients included in our study group have variety of diseases that may be difficult for the clinicians and radiologists to diagnose even with CT examination and there may be delays in diagnoses waiting for laboratory analysis. As CT exam is readily available in most clinics and immediate analysis of images is possible, if any CT feature has prognostic value it can help clinicians in managing the patients even without the confirmed clinical diagnosis that is not yet available.

Limitation

This is a single institutional study that included small number of patients. The group of patients in this study had variety of clinical diagnosis that may be heterogenous and not be categorized into groups of specific diseases. This may reflect differences in results depending on percentage of diseases that are included in a group. However, this group of patients was acquired from tertiary hospital that treats many leukemic patients and also the percentage of diseases that are included show similar incidence with that of the literature. Thus, the patient group may rather correctly reflect the heterogeneity of patients we can encounter on clinical settings.

14

Conclusion

In cases when exact diagnosis of a patient may not be properly diagnosed using clinical and imaging studies, small bowel wall thickness can be measured and mesenteric stranding can be sought and used as prognostic factors that have high negative predictive value. This can provide clinicians relieving information in managing leukemic patients with abdominal pain if the patient does not have small bowel wall thickening or mesenteric stranding. When a patient presents with small bowel wall thickening and mesenteric stranding, this information may give suggestions to clinicians in determining more intensive therapeutic approach.

15

Figures

(A) (B)

Figure 1. A 53 year old female with AML who complained of acute abdominal pain and fever was clinically diagnosed as CMV enterocolitis. This patient was in the mortality group. (A) Contrast-enhanced axial CT scan shows multi-segmental thickening of small bowels (arrows). (B) Contrast-enhanced axial CT scan shows combined segmental large bowel wall thickening (arrow) and mesenteric stranding (arrowhead).

16

(A) (B)

Figure 2. A 14 year old male with AML who complained of acute abdominal pain especially at right lower quadrant was clinically diagnosed as neutropenic

enterocolitis. This patient was in the non-mortality group. (A) Contrast-enhanced axial CT scan shows thickening of cecum (arrow). (B) Contrast-enhanced axial CT scan shows combined ascending and transverse colon wall thickening (arrow). There were no signs of small bowel wall thickening or mesenteric stranding.

17

(A) (B)

Figure 3. A 57 year old female with AML who complained of acute abdominal pain, fever, and diarrhea was clinically diagnosed as neutropenic enterocolitis. This patient was in the mortality group. (A) Contrast-enhanced axial CT scan shows thickening of cecum (arrow) with pericolic fat infiltration. (B) Contrast-enhanced axial CT scan shows multi-segmental small bowel wall thickening (arrow) with mesenteric stranding.

18

Mortality group Non-mortality group p-value

Mean age 45.86 39.77 0.2591 Sex distribution Male Female 9 (42.86%) 12 (57.14%) 40 (57.97%)29 (42.03%) 0.3335 Neutropenia 12 (57.14%) 31 (44.92%) 0.4641 fever 15 (71.43%) 40 (57.97%) 0.3941

Clinical diagnosis Number of cases

Ischemic enterocolitis 5 (23.81%)

CMV enterocolitis 4 (19.05%)

GVHD 3 (14.29%)

Neutropenic enterocolits 2 (9.52%)

No evident cause of acute abdomen 2 (9.52%)

Tables

Table 1. Clinical characteristics of patients in the mortality group and the non-mortality group.

19

Mortality group Non-mortality

group p-value

Bowel wall thickening 16 (76.19%) 35 (50.72%) 0.0702

Small bowel thickness Mean

95% CI for the mean Standard deviation 4.6667 mm 3.0488 to 6.2846 3.5543 2.7826 mm 2.2105 to 3.3548 2.3817 0.0062 Large bowel thickness

Mean

95% CI for the mean Standard deviation 8.1905 mm 6.1114 to 10.2696 4.5675 5.8986 mm 4.5277 to 7.2694 5.7064 0.0962

Small bowel distension 3 (14.29%) 1 (1.45%) 0.0581

Fluid filled bowel 13 (61.9%) 31 (44.93%) 0.2658

Abnormal mucosal enhancement 4 (19.05%) 8 (11.59%) 0.6072 Pneumatosis intestinalis 0 (0%) 1 (1.45%) 0.5264 Bowel perforation 0 (0%) 2 (2.9%) 0.9554 Mesenteric stranding 11 (52.38%) 18 (26.09%) 0.0465 Pericolic stranding 7 (33.34%) 14 (20.29%) 0.3455 Peritoneal enhancement 0 (0%) 1 (1.45%) 0.5264 Retroperitoneal lymphadenopathy 4 (19.05%) 13 (18.84%) 0.7666 Vascular thrombosis 0 (0%) 2 (2.9%) 0.9554 Ascites 12 (57.14%) 30 (43.48%) 0.3960 Pleural effusion 6 (28.57%) 9 (13.04%) 0.1810 Generalized edema 1 (4.76%) 0 (0%) 0.5265 Hepatomegaly 9 (42.86%) 20 (28.99%) 0.3554 Periportal edema 8 (38.1%) 12 (17.39%) 0.0893 liver abscess 0 (0%) 1 (1.45%) 0.5264 Splenomegaly 5 (23.81%) 5 (7.25%) 0.0859 Splenic infarction 5 (23.81%) 5 (7.25%) 0.0859 Biliary abnormalities 0 (0%) 1 (1.45%) 0.5264 Pancreatitis 0 (0%) 5 (7.25%) 0.4680 Hydronephrosis 1 (4.76%) 0 (0%) 0.5265

20

Clinical diagnosis Number of cases

No evident cause of acute abdomen 23 (25.56%)

Infectious enterocolitis 13 (14.44%) Neutropenic enterocolitis 12 (13.33%) Acute pancreatitis 7 (7.78%) Ischemic colitis 5 (5.56%) GVHD 3 (3.33%) Acute cholecystitis 3 (3.33%) Acute appendicitis 2 (2.22%) Granulocytic sarcoma 2 (2.22%)

CT findings Sensitivity Specificity Positive

predictive value

Negative predictive

value Small bowel thickness

> 3 mm (A) 52.38% 79.71% 44% 84.6%

Mesenteric stranding

(B) 52.38% 73.91% 37.93% 83.61%

Combination of A & B 42.86% 85.51% 47.37% 83.1%

Table 4. CT findings of patients in the mortality group and the non-mortality group.

21

Bibliography

1. C. Hordonneau, “Abdominal complications following neutropenia and haematopoietic stem cell transplantation: CT findings” Clin Radiol, Vol. 68, pp. 620-626, 2013.

2. J. S. Cornes, “Leukaemic lesions of the gastrointestinal tract” J Clin Pathol, Vol. 15, pp. 305-313, 1962.

3. J. C. Prolla, “The Gastrointestinal Lesions and Complications of the Leukemias” Ann

Intern Med, Vol 61, pp. 1084-1103, 1964.

4. E. C. Ebert, “Gastrointestinal manifestations of leukemia” J Gastroenterol Hepatol, Vol. 27, pp. 458-463, 2012.

5. J. A. Hawkins, “Acute abdominal conditions in patients with leukemia” Am J Surg,

Vol. 150, pp. 739-742, 1985.

6. J. Y. Byun, J“CT features of systemic lupus erythematosus in patients with acute abdominal pain: emphasis on ischemic bowel disease” Radiology, Vol. 211, pp. 203-209 1999.

7. C. Cartoni, “Neutropenic enterocolitis in patients with acute leukemia: prognostic significance of bowel wall thickening detected by ultrasonography” J Clin Oncol, Vol. 19, pp. 756-761, 2001.

8. A. Shimoni, “CT in the clinical and prognostic evaluation of acute graft-vs-host disease of the gastrointestinal tract” Br J Radiol, Vol. 85, pp. e416-423, 2012.

9. J. K. Fisher, “Abnormal colonic wall thickening on computed tomography” J Comput

Assist Tomogr, Vol. 7, pp. 90-97, 1983.

10. C. F. Dietrich, “Sonographic signs of neutropenic enterocolitis” World J

Gastroenterol, Vol. 12, pp. 1397-1402, 2006.

11. E. C. Benya, “Abdominal complications after bone marrow transplantation in children: sonographic and CT findings” Am J Roentgenol, Vol. 161, pp. 1023-1027, 1993.

12. H. K. Ha, “Differentiation of simple and strangulated small-bowel obstructions: usefulness of known CT criteria” Radiology, Vol. 204, pp. 507-512, 1997.

13. A. F. Cardona Zorrilla, “Systematic review of case reports concerning adults suffering from neutropenic enterocolitis” Clin Transl Oncol, Vol. 8, pp 31-38, 2006.

14. D. Mullassery, “Diagnosis, incidence, and outcomes of suspected typhlitis in oncology patients--experience in a tertiary pediatric surgical center in the United Kingdom” J Pediatr Surg, Vol. 44 pp. 381-385, 2009.

15. J. H. Lee, “Gastrointestinal complications following hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in children” Korean J Radiol, Vol. 9, pp. 449-457, 2008.

16. M. Schmit, “CT of gastrointestinal complications associated with hematopoietic stem cell transplantation” Am J Roentgenol, Vol. 190, pp. 712-719, 2008.

17. S. P. Spencer, “The acute abdomen in the immune compromised host” Cancer

Imaging, Vol. 8, pp. 93-101, 2008.

18. K. M. Horton, “CT evaluation of the colon: inflammatory disease” Radiographics, Vol. 20, pp. 399-418, 2000.

19. S. A. Teefey, “Sonographic diagnosis of neutropenic typhlitis” Am J Roentgenol, Vol. 149, pp. 731-733, 1987.

20. M. P. Frick, “Computed tomography of neutropenic colitis” Am J Roentgenol, Vol. 143, pp. 763-765, 1984.

21. M. B. McCarville, “Typhlitis in childhood cancer” Cancer, Vol. 104, pp. 380-387, 2005.

22. E. Takaoka, “Neutropenic colitis during standard dose combination chemotherapy with nedaplatin and irinotecan for testicular cancer” Jpn J Clin Oncol, Vol. 36, pp.

22

60-63, 2006.

23. F. Kuffer, “Surgical complications in children undergoing cancer therapy” Ann Surg, Vol. 167, pp. 215-219, 1968.

24. R. M. Weetman, “Latent onset of clinical pancreatitis in children receiving L-asparaginase therapy” Cancer, Vol. 34, pp. 780-785, 1974.

25. W. Wiesner, “CT of acute bowel ischemia” Radiology, Vol. 226, pp. 635-650, 2003. 26. B. J. Bartnicke, “CT appearance of intestinal ischemia and intramural hemorrhage”

Radiol Clin North Am, Vol. 32, pp. 845-860, 1994.

27. G. T. Jones, “Gastrointestinal necrosis in acute leukemia: a complication of induction therapy” Cancer Invest, Vol. 1, pp. 315-320, 1983.

28. S. Y. Mahgerefteh, “Radiologic imaging and intervention for gastrointestinal and hepatic complications of hematopoietic stem cell transplantation” Radiology, Vol. 258, pp. 660-671, 2011.

29. I. D. Kirkpatrick, “Gastrointestinal complications in the neutropenic patient: characterization and differentiation with abdominal CT” Radiology, Vol. 226, pp. 668-674, 2003.

30. C. A. Dasanu, “Chronic lymphocytic leukemia presenting with cholecystitis-like symptoms and gallbladder wall invasion” South Med J, Vol. 103, pp. 482-484, 2010. 31. S. H. Bloom, “Cholecystitis as the presenting manifestation of acute myeloid leukemia: report of a case” Am J Hematol, Vol. 70, pp. 254-256, 2002.

32. M. Barcos, “An autopsy study of 1206 acute and chronic leukemias (1958 to 1982)”

Cancer, Vol. 60, pp. 827-837, 1987.

33. W. Johnson, “Acute appendicitis in childhood leukemia” J Pediatr, Vol. 67, pp. 595-599, 1965.

34. E. Altinel, “Typhlitis in acute childhood leukemia” Med Princ Pract, Vol. 21, pp. 36-39, 2012.