Emerald Article: Informal relations: A look at personal influence in media

relations

Jae-Hwa Shin, Glen T. Cameron

Article information:

To cite this document: Jae-Hwa Shin, Glen T. Cameron, (2003),"Informal relations: A look at personal influence in media relations", Journal of Communication Management, Vol. 7 Iss: 3 pp. 239 - 253

Permanent link to this document:

http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/13632540310807395

Downloaded on: 09-10-2012

Citations: This document has been cited by 12 other documents To copy this document: permissions@emeraldinsight.com This document has been downloaded 650 times since 2005. *

Users who downloaded this Article also downloaded: *

Nicolas Rolland, Renata Kaminska-Labbé, (2008),"Networking inside the organization: a case study on knowledge sharing", Journal of Business Strategy, Vol. 29 Iss: 5 pp. 4 - 11

http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/02756660810902260

Raef T. Hussein, 1990"Understanding and Managing Informal Groups", Management Decision, Vol. 28 Iss: 8

http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/00251749010000038

Raef T. Hussein, 1989"Informal Groups, Leadership and Productivity", Leadership & Organization Development Journal, Vol. 10 Iss: 1 pp. 9 - 16

http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/EUM0000000001130

Access to this document was granted through an Emerald subscription provided by PUSAN NATIONAL UNIVERSITY For Authors:

If you would like to write for this, or any other Emerald publication, then please use our Emerald for Authors service. Information about how to choose which publication to write for and submission guidelines are available for all. Please visit www.emeraldinsight.com/authors for more information.

About Emerald www.emeraldinsight.com

With over forty years' experience, Emerald Group Publishing is a leading independent publisher of global research with impact in business, society, public policy and education. In total, Emerald publishes over 275 journals and more than 130 book series, as

Informal relations: A look at

personal influence in media relations

Received (in revised form): 10th December, 2002Jae-Hwa Shin

is a doctoral student in the Missouri School of Journalism. She has published many research papers on media relations in a different cultural context. She also has many years’ professional experience in public relations, particularly media relations, as public relations manager for the Federation of Korean Industries.

Glen T. Cameron

is the Maxine Wilson Gregory Chair of Journalism Research in the Missouri School of Journalism. As author of more than 100 books, chapters, articles and convention papers, he has received numerous national awards for his entire body of work. He has guest lectured on public relations theory and practice in Asia, Europe and Central America.

Abstract Public relations practitioners and journalists in South Korea (n= 300) were surveyed regarding their perceptions of the influence of 11 types of informal relations (ranging from press tours to perks and bribes) on the news. Using coorientational analysis, the perceptions of each group regarding the ethics of informal relations were also investigated. The two groups reported significantly different perceptions of the influence of informal relations on the news, as well as the ethics of informal relations. Practitioners perceive greater influence of informal relations on news coverage as well as on news content, and perceive informal relations as more ethical or acceptable in

practice than do journalists. Regarding informal relations, journalists’ perceived gap between their own ethical values and their predictions of practitioners’ ethical values is bigger than the converse. Finally, practitioners’ misunderstanding of journalists’ ethical values is greater than journalists’ misunderstanding of practitioners’ ethical values. This study indicates that even in a culture where press clubs and interpersonal media

relations are the norm and could be expected to breed familiarity, attitudinal differences between practitioners and journalists are striking.

KEYWORDS: international public relations, source–reporter dynamics, ethics, personal influence, cultural communication

INTRODUCTION

This study will examine potential misunderstanding and discord between public relations practitioners and journalists reflected in the scholarly research. In South Korea practitioners and journalists each believe that the other exercises undue power over the news, particularly through informal relations, and subscribe to negative perceptions about each other and unethical values about the influence of informal relations. Informal relations influence the news and thus, involve the

professional ethics of both practitioners and journalists. Journalists depend on informal relations with practitioners for gathering news, but mistrust the power that informal relations exert on the news. Practitioners are in a dilemma between strategic values for disseminating information through informal relations with journalists and ethical values involved in influencing the news. How do the two parties perceive themselves and each other in terms of the influence of informal relations on the news and the ethical values of informal relations? Jae-Hwa Shin Missouri School of Journalism Columbia, MO 65211-1200, USA. Tel: +1 573 443 7214; Fax: +1 573 443 7214; E-mail: js389@mizzou.edu

This study focuses on the concept of informal relations, media relations practices involving influence on the news, and related ethical values in Korea. Informal relations include the following eleven practices:

— unofficial calls — private meetings

— regional/alumni/blood relations — press tours

— travels for a press club

— bargaining advertising to news coverage — exercising power through managers/

editors of news bureaux — perks including dinner/drinking — activities for friendship such as golf/

climbing

— presents and free tickets — bribes

through which information flows and influences the news in an informal and unofficial way. Informal relations are distinct from formal and official media relations such as press releases, news conferences, speeches, interviews, reports, hearings and official proceedings.

LITERATURE REVIEW

The relationship between public relations practitioners and journalists, and their perceptions of each other have been studied. Most previous studies regard the relationship between practitioners and journalists as a source–reporter relationship and confirm the influence of public relations on the news. They also corroborate the existence of

misunderstanding and antagonism toward each other in the agenda-building process and the unethical involvement of both professions.

Relationship between public relations practitioners and journalists

The relationship between practitioners as source and journalists as reporter can be

traced to a conceptual model of communication by Westley and

MacLean.1Giber and Johnson2applied the model to source and reporter relationships and defined the interdependent roles of source and reporter. The notion of role interdependency was discussed by Cutlip et al.3In the model of the role and impact of source in news, Cameron et al.4also suggested the relationship between practitioners and journalists as source and reporter.

Public relations practitioners serve as one of the most influential sources of news through their ability to subsidise

information for journalists.5Shoemaker and Reese6defined sources as ‘external suppliers of raw materials, whether speeches, interviews, corporate reports or government hearings’ and indicated ‘sources have a tremendous effect on mass media content because journalists can’t conclude in their news what they don’t know’. Berkowitz7also defined the information subsidies as routine channels such as news releases, news conferences, preplanned events or official proceedings.

The influence of public relations on the news as information subsidy has resulted in numerous statistical estimates. Cutlip8 reported that 35 per cent of newspaper content is influenced by public relations sources. Schabacker9estimated that public relations sources serve as news sources for 10 to 51 per cent of the news content in newspapers, radio, television and wire service dispatches. Other researchers have estimated that 25 to 50 per cent or even as high as 80 per cent of the news content is initiated by public relations sources.10–14

On the other hand, Baxter15argued that public relations sources have little direct influence on the news, but indirectly influence journalists’ perceptions. Turk16 found that the influences of public relations on the news agenda has a moderate effect. Even these studies

of source in the agenda-building process and influences on the news.

Cameron et al.17constructed the concept about the source role and impact of public relations in terms of interpersonal

relationships, organisational dynamics and societal impacts. This research examines public relations’ influence on the news with such interpersonal, organisational and societal factors as unofficial calls, private meetings, regional, alumni or blood relationship (a kind of kinship tie), press tours for reporters, press tours for travel writers, bargaining advertising to news coverage, exercising power through managers or editors of news bureaux, perks including dinner or drinking, activities for friendship such as golf or climbing, presents and free tickets, and even bribes in the Korean context.

Some scholars discussed the

interpersonal, organisational and societal factors and the impact of public relations practices in Korea.18–21They indicated that, in the source and reporter

relationship in Korea, information often flows informally, unofficially and even secretly, influencing the news indirectly rather than directly. The interpersonal, organisational and societal factors can be regarded as informal relations distinct from formal relations, including news releases, speeches, interviews, reports or hearings, through which information flows formally, officially and more explicitly.

For example, Kim22analysed Korean society and its communication system, which has informal, unofficial, secret and implicit aspects; Gang23discussed private meetings with dinner or drinking are used by journalists for gathering news; Kang24 indicated that the press are controlled by bargaining advertising and offering bribes and that practitioners are directly involved in those practices; Shin25discussed

interpersonal factors such as perks and bribes, and the negative implications for public relations practices in Korea. These

are a few of the studies which can be related to some aspects of informal relations.

Perceptions and cross-perceptions between public relations

practitioners and journalists

A number of studies have also examined the perceptions and cross-perceptions between practitioners and journalists regarding the source and reporter

relationship and its influence on the news, describing their perceptions as sometimes adversarial or sometimes cooperative, and always sceptical about each other.

Consistently, journalists have held suspicious or negative views of public relations and practitioners, with some indication from a review of USA findings that the playing field has become more level in recent years,26particularly with the diminished credibility of journalism and the more professional or managerial approach of practitioners.

Aronoff27found that journalists have negative attitudes toward public relations and practitioners, although ‘many journalists acknowledge the contribution made by public relations to the process of news production’. He concluded that journalists have news value orientations and view practitioners as low in source credibility. Jeffers28also found a skewed perception among journalists. He found that journalists perceived the relationships with practitioners as slightly cooperative whereas practitioners saw journalists as much more so. Journalists believed practitioners lacked ethics, but those with whom they had regular contact were significantly more ethical. He concluded that the practitioner/journalist relationship is not the ‘adversary one suggested by conventional journalistic wisdom,’ but has the ‘apparent bi-level nature of status and perceptions of cooperation.’ Belz et al.29 found that the two groups view the role of public relations differently. Journalists have

negative views of practitioners for having hidden agendas, withholding information and compromising ethics, as well as for their inherent role as advocates.

Some research has applied the Chaffee-McLeod coorientation model to identify nuances in the difference between

practitioners and journalists when it comes to professionalism and news values. Ryan and Martinson30found agreement between practitioners and journalists regarding news values, but journalists inaccurately perceived the news values of practitioners. Kopenhaver31found that journalists tend to believe that practitioners were more inclined to deceive the press by ‘depicting the subject in a favourable light’, and they were not quite accurate in predicting practitioners’ perceptions. Stegall and Sanders32replicated and corroborated the findings.

In contrast to most studies, Swartz33 suggested that both practitioners and journalists have much in common, but the difference are ‘based less upon the skills that each group uses than how each occupation is perceived by others’. Brody34saw little evidence to support an adversarial relationship between journalists and practitioners. He found that although journalists and practitioners disagree on four of eight ethical factors (ie fair dealing, conduct in accordance with public interest, conflict of interests, readily identifying clients/motivations), they agree substantially on three factors (ie truth, accuracy and good taste, safeguarding confidence, avoiding corruption of channels of communication, intentional communication of falsehoods/

misinformation. Sallot et al.35surveyed journalists’ perceptions and

cross-perceptions of their own and each other’s news values and the influence of public relations on the news. They found that both held similar news values, although journalists reported a greater lack of perception of the similarity.

Regardless of the nature and extent of perceptual differences, public relations is always perceived more negatively than its media counterpart. Cline36found that practitioners were perceived as less ethical and less professional than journalists. Turk37found that journalists would use news releases with no obvious self-serving purpose, and in general, journalists prefer to use information they gather on their own, suggesting their concern with the credibility of public relations sources of information. Similarly, Pincus et al.38 found that journalists tend to believe in the anatomy of their news selection process. These studies suggest that journalists do not view practitioners as serious sources because their motivations are self-serving, which increases the negative perception of public relations.

Practitioners reported that

unprofessional practices in public relations contribute to journalists’ negative views.39 Ryan and Martinson40concluded that the self-interest inherent in an advocacy role leads both journalists and practitioners to view practitioners as less forthright, and thus, practitioners lack source credibility. Spicer41identified several negative perceptions of public relations and discussed how journalists subjectively embed negative connotations about public relations through their use of the term public relations.

Accordingly, the negative perceptions of public relations and practitioners held by journalists and even practitioners

themselves are related mostly to the advocacy role inherent in the function of a news source and partly to unprofessional practices. This cannot help practitioners avoid stereotypes about being unethical. Pratt42found that practitioners perceived the image of their professional ethics to be poor, whereas Saunders43suggested that practitioners encountered no ethical dilemmas in their jobs and most of them were unsure when withholding

information could be considered ethical. The professional ethics of public

relations practitioners was also discussed by Pearson.44He posited a calculus of

communicative ethics based on mutuality and rationality. Such a system, however, may not only be unrealistic, but may also be morally inferior to an ontological approach relying on moral standards and values that override a process of mutuality and rationality, especially when

worldviews collide over an issue.45–48 According to different interpersonal, organisational and societal factors, practitioners may differently practise public relations, and thus have different perceptions of the influence of public relations on the news and related ethical values. Informal relations, a part of media relations in Korea, influences the news in many ways, particularly through a press club system managed for journalists gathering information as well as for practitioners disseminating information.

Informal relations are not unique to Korea, as variations on practices of informal media relations are documented throughout SE Asia. Sociologists and cultural studies scholars such as Hofstede and Hall have identified characteristics of Asian societies that value implicit, closed, private, informal and personal interaction through a structure and customs that bring individuals together. In Asia, this system is found in the press club arrangement that brings journalists and public relations practitioners together regularly and in conventional ways. Public relations scholars have confirmed that these characteristics are evident in SE Asia.49–51 Shin and Cameron summarised these tendencies in Asian news disseminating or gathering systems, particularly those built around the press club systems, that reflect Eastern cultural systems:

‘Different from media relations in the Western countries, public relations

practitioners in Asian countries such as India, Japan and Korea practice implicit, indirect, interpersonal and informal forms of communication with journalists because the media tend to mistrust information that is officially publicized by organisations.’52

Shin and Cameron continue with the following contrast of Asian and American media relations:

‘communication differs from American communication in terms of four factors: context, structure, process, and relationship. Its [Korean and we would argue Asian] context is ‘‘implicit’’ rather than ‘‘explicit,’’ its structure is based on ‘‘collectivism’’ rather than the ‘‘individualism’’ of the West, its process is ‘‘bottom up’’ instead of ‘‘top down,’’ and its relationship is oriented to the ‘‘long-term’’ relationship instead of the ‘‘short-term’’ relationship in the West. This approach is useful to propose the cultural variance in the conflictual source-reporter relationship in different cultures.’53

Given the widespread use of informal relations to cultivate source–reporter interaction, very little research has been carried out. No study explicitly shows practitioners’ and journalists’ perceptions and cross-perceptions of their informal relations in terms of both the influence on the news and related ethical values. Therefore, the debate regarding both the influence of informal relations on the news and related ethical values is real as well as meaningful to the parties involved. The underlying persistent premises are that interpersonal relationships between practitioners and journalists influence the news, and that this cannot help

practitioners and journalists avoid unethical involvement.

This research, built on the inevitable conflict between practitioners and

journalists, could enhance understanding of the source and reporter relationship by determining practitioners’ and journalists’ perceptions of the influences of informal

relations on the news, and by comparing their own perceptions and each group’s perceptions of the other regarding the ethical values of informal relations.

Although findings here are derived from the Korean public relations–journalist communication system, the study posits interesting tendencies typical of any news system of informal relations throughout the Pacific Rim countries where a common cultural backdrop has been well established under the Eastern–Western rubric.

RESEARCH QUESTIONS

This study had both public relations practitioners and journalists assess their own perceptions of the influence of informal relations on the news, and their own perceptions and their perceptions of the other group’s ethical values of

informal relations. It was believed that the two groups would exhibit different perceptions of the influence of informal relations on the news, with different ethical values attributed to informal relations between practitioners and journalists resulting in misperceptions of each other. Practitioners would believe that informal relations exert a more powerful influence than journalists would believe when practitioners and journalists were asked to estimate the power of informal relations in covering the news and in shaping the news agenda. The following hypotheses distinguish the influence of informal relations on both the extent and quality of news regarding a given topic using two related terms: news coverage and news content. News coverage is operationalised as the amount or extent of news for a topic. News content is associated with the valence of the news coverage, that is, the nature of the content in terms of favourability/ unfavourability for the organisation being covered in the news. Therefore, the first hypothesis is:

H1: Public relations practitioners and journalists will perceive differently the influence of informal relations on the news.

H1a: The perceived influence of informal relations on news coverage will be greater for practitioners than for journalists. H1b: The perceived influence of informal

relations on the news content will be greater for practitioners than for journalists.

It was also predicted that practitioners would be more in favour of informal relations than journalists, when

practitioners and journalists were asked about informal relations that practitioners and journalists could ethically approve. To employ coorientational analysis,

agreement, congruency and accuracy between practitioners and journalists were examined. Agreement is the comparison of the two groups’ self evaluation.

Congruency is the comparison between one group’s self-evaluation and their evaluation of the other group. Accuracy is the determination of the gap between one group’s prediction of the other group’s self-evaluation and the other group’s actual self-evaluation. The second hypothesis is:

H2: Public relations practitioners and

journalists will perceive the ethical values of informal relations differently.

H2a: Practitioners will perceive informal relations as more ethical and acceptable in practice than will journalists. H2b: The gap between journalists’ ethical

values and their predictions about practitioners’ ethical values will be greater than the gap between practitioners’ ethical values and their predictions about journalists’ ethical values in terms of informal relations. H2c: The gap between practitioners’

predictions about journalists’ ethical values and the actual ethical values of journalists will be greater than the gap between journalists’ predictions about practitioners’ ethical values and the

actual ethical values of practitioners in terms of informal relations.

METHODS

Print questionnaires were delivered to 330 media professionals (165 public relations practitioners and 165 journalists) in Korea. The sample consisted of randomly selected practitioners working at corporations, non-profit organisations and agencies, and journalists working at daily newspaper offices, broadcasting stations and wire services. The two demographic markets were selected as sampling frames for greater diversity. A total of 300 usable responses were gathered with personal follow-up to collect completed surveys, representing a 91 per cent response rate. The 150 public relations practitioners were randomly selected from the members listed in the 1999 Korea Public Relations Association, with 76 per cent of all practitioner respondents being male, suggesting that practitioners involving media relations are mainly male in Korea. About 64 per cent were aged 30–39. Respondents had diverse affiliations, with in-house predominant over agency, including Samsung, Hyundai, SK and LG, as well as Korea Telecommunications, Korea Bank of Industries, Yonsei Hospital, Korea Public Relations Agency and Communications Korea Agency.

The 150 journalists surveyed were randomly selected from the 1999

Journalists Association of Korea, 90.6 per cent of journalist respondents were male, which also suggests that journalists are also mainly male in Korea. About 76 per cent were aged 30–39. Journalist respondents also had diverse affiliations, with print predominant over broadcast, including Chosun Daily, Joongang Daily, DongA Daily, Hankuk Daily, Kyunghyang Daily, The Korea Times, The Korea Herald, Maekyung Economic Daily and Korea Economic Daily, as well as KBS News,

MBC News, SBS News, CBS News and Yonhap Wire.

The survey asked respondents to assess the degree of two measures of ‘influence’ on the news by measuring on a five-point Likert-type scale, where one was least and negative, and five was most and positive.

To measure the perceived power of informal relations in setting the news agenda, two measures of ‘influence’ were asked for each of the 11 types of informal relations such as private meetings, press tours, bargaining for coverage in exchange for advertising, bribes and etc. The two measures were:

— ‘Informal relations has an influence on what news, ie the amount of news coverage, is presented to the public’ — ‘Informal relations have an influence on

the way news, ie the favourable light of news content, is presented to the public’.

Both questions measure the perceived power of informal relations in setting the news agenda.

The survey also asked respondents to assess the ‘ethical value’ of informal relations, which can be ethically approved and utilised. A 1–5 scale was also used to measure the ethical value questions, with one being ‘strongly disagree’ and five ‘strongly agree.’ In addition, respondents were asked to measure their perceptions of the other profession’s ethical values of informal relations using the same scale.

To measure the perceived and cross-perceived ethical values of informal relations, two measures of ‘ethical value’ with each of the 11 items of informal relations were asked:

— ‘Informal relations could be ethically approved and utilised’

— ‘The other profession perceives that informal relations could be ethically approved and utilized’.

While both questions measure ethical

values, the first measures the perceived ethical values of practitioners and journalists, and the second measures the cross-perceived ethical values of the other.

RESULTS

Perceptions of the influence of informal relations on the news

Public relations practitioners and

journalists were asked two sets of questions of informal relations’ influence on the news with each of the 11 types of personal influence. It was predicted that both professions would differently perceive that informal relations exert influence on the news.

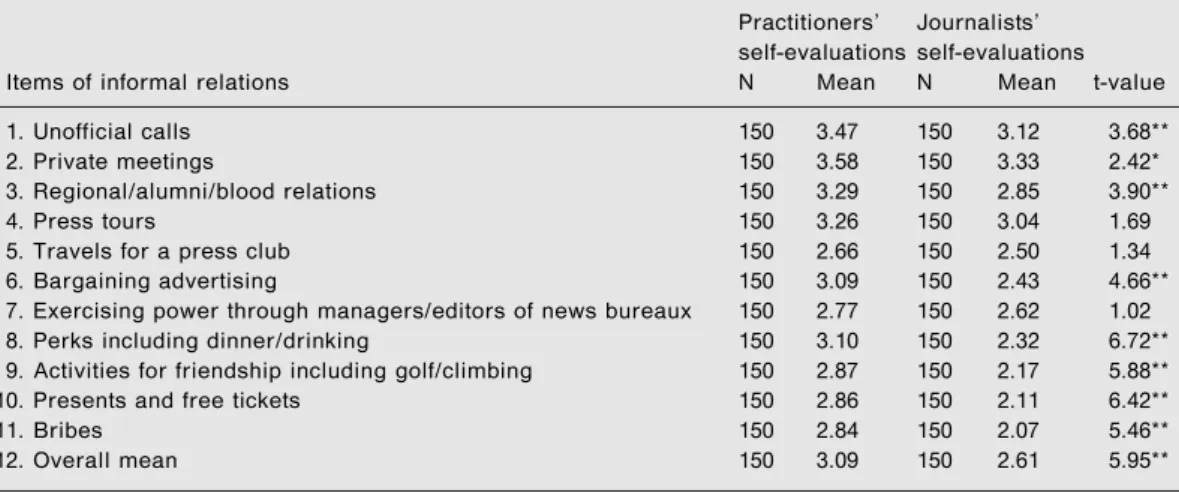

Tables 1 and 2 present practitioners’ and journalists’ self-reported influence of informal relations on the news respectively regarding the amount of news coverage and the favourable light of news content. The findings support the hypothesis that the professions would perceive different degrees of influence.

As can be seen in Tables 1 and 2, both groups perceived influence of informal relations, with means ranging from 1.70 to 3.58 on a 1–5 scale, where five represented strong influence. Moreover, practitioners perceived significantly greater influence

than journalists regarding the influence of informal relations on what news is presented and on the way news is presented.

Practitioners perceived greater influence of informal relations on the amount of news coverage than journalists. The primary perceptual difference regarded the influence of ‘perks including dinner/ drinking’. Item-by-item comparisons of practitioners’ perceptions and journalists’ perceptions are presented in Table 1.

Practitioners also perceived greater influence of informal relations on the favourable light of news content than journalists. The primary perceptual difference also regarded the influence of perks including dinner/drinking. Item-by-item comparisons of practitioners’

perceptions and journalists’ perceptions are presented in Table 2.

Perceptions and cross-perceptions of the ethical values of informal relations

Public relations practitioners and journalists were asked two sets of questions regarding the ethical values of informal relations with each of the 11 items. It was predicted that both

professions would perceive their own and Table 1: Practitioners’ and journalists’ perceptions of the influence of informal relations on the news: The amount of news coverage

Practitioners’ Journalists’ self-evaluations self-evaluations

Items of informal relations N Mean N Mean t-value

1. Unofficial calls 150 3.18 150 3.40 -2.16*

2. Private meetings 150 3.52 150 3.48 0.35

3. Regional/alumni/blood relations 150 3.13 150 2.50 5.26**

4. Press tours 150 3.22 150 2.89 2.18*

5. Travels for a press club 150 2.41 150 2.06 2.76**

6. Bargaining advertising 150 3.04 150 2.16 6.14**

7. Exercising power through managers/editors of news bureaux 150 2.90 150 2.80 0.64

8. Perks including dinner/drinking 150 2.94 150 1.92 8.78**

9. Activities for friendship including golf/climbing 150 2.69 150 1.74 7.79**

10. Presents and free tickets 150 2.59 150 1.73 7.13**

11. Bribes 150 2.61 150 1.70 6.92**

12. Overall mean 150 2.94 150 2.40 6.94**

each other’s ethical values of informal relations differently.

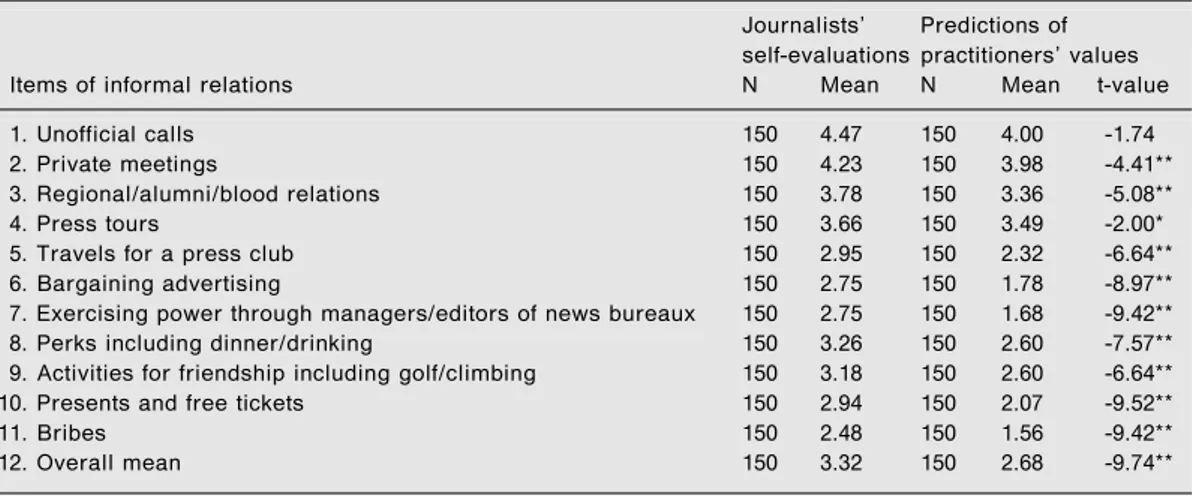

As can be seen in Table 3, both groups showed their own ethical values of informal relations, with means ranging from 1.58 to 4.45 on a 1–5 scale, where one represented strong objection. Moreover, ratings by practitioners were significantly more favourable than journalists in identifying which informal relations can be ethically approved and utilised. The strongest perceptual difference regarded the ethical value of ‘presents and free tickets’.

Journalists saw less similarity between their ethical values and their perceptions of practitioners’ ethical values than

practitioners. Comparing their own ethical values of informal relations, journalists thought that practitioners would perceive informal relations as less ethical.

Practitioners, however, thought that journalists would perceive informal relations as more ethical.

Journalists’ primary perceptual difference regarded the ethical value of ‘exercising power through managers/ editors of news bureaus’, whereas Table 2: Practitioners’ and journalists’ perceptions of the influence of informal relations on the news: The favourable light of news content

Practitioners’ Journalists’ self-evaluations self-evaluations

Items of informal relations N Mean N Mean t-value

1. Unofficial calls 150 3.47 150 3.12 3.68**

2. Private meetings 150 3.58 150 3.33 2.42*

3. Regional/alumni/blood relations 150 3.29 150 2.85 3.90**

4. Press tours 150 3.26 150 3.04 1.69

5. Travels for a press club 150 2.66 150 2.50 1.34

6. Bargaining advertising 150 3.09 150 2.43 4.66**

7. Exercising power through managers/editors of news bureaux 150 2.77 150 2.62 1.02

8. Perks including dinner/drinking 150 3.10 150 2.32 6.72**

9. Activities for friendship including golf/climbing 150 2.87 150 2.17 5.88**

10. Presents and free tickets 150 2.86 150 2.11 6.42**

11. Bribes 150 2.84 150 2.07 5.46**

12. Overall mean 150 3.09 150 2.61 5.95**

Note. ** p50 .01, * p 5 0.05

Table 3: Comparison of practitioners’ and journalists’ ethical values of informal relations: ‘Agreement’ between practitioners and journalists

Practitioners’ Journalists’ self-evaluations self-evaluations

Items of informal relations N Mean N Mean t-value

1. Unofficial calls 150 4.45 150 4.00 5.60**

2. Private meetings 150 4.27 150 3.98 3.54**

3. Regional/alumni/blood relations 150 3.45 150 3.37 0.76

4. Press tours 150 3.62 150 3.51 1.02

5. Travels for a press club 150 2.32 150 2.33 -0.12**

6. Bargaining advertising 150 2.33 150 1.79 4.93**

7. Exercising power through managers/editors of news bureaux 150 2.09 150 1.68 3.90**

8. Perks including dinner/drinking 150 3.06 150 2.61 4.22**

9. Activities for friendship including golf/climbing 150 2.96 150 2.61 3.14**

10. Presents and free tickets 150 2.75 150 2.10 5.82**

11. Bribes 150 1.92 150 1.58 3.24**

12. Overall mean 150 3.02 150 2.68 5.62**

Note. ** p5 0.01, * p 5 0.05

practitioners’ primary perceptual difference regarded the ethical value of ‘bribes’. Item-by-item comparisons of practitioners’ and journalists’ ethical values and their

perceptions of the other’s ethical values are shown in Tables 4 and Table 5

respectively.

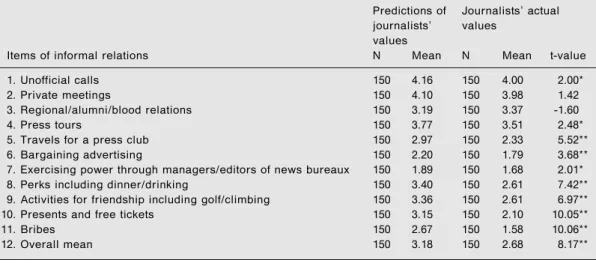

On the other hand, the practitioners’ cross-perceived gap between their

prediction of journalists’ ethical values and the journalists’ actual ethical values is significantly greater than the journalists’ cross-perceived gap between their predictions of practitioners’ ethical values

and the practitioners’ actual ethical values regarding informal relations. Practitioners were inaccurate in predicting journalists would perceive informal relations as being more ethical than in reality. Likewise, journalists wrongly predicted that practitioners would perceive informal relations as being more ethical than they were.

Practitioners’ primary prediction gap regarded the ethical value of ‘bribes’, whereas journalists’ primary prediction gap regarded the ethical value of ‘activities for friendship including golf/climbing’.

Item-Table 4: Comparison of practitioners’ ethical values and practitioners’ predictions of journalists’ ethical values: ‘Congruency’ of practitioners

Practitioners’ Predictions of self-evaluations journalists’ values

Items of informal relations N Mean N Mean t-value

1. Unofficial calls 150 4.45 150 4.16 4.71**

2. Private meetings 150 4.27 150 4.10 2.64**

3. Regional/alumni/blood relations 150 3.45 150 3.21 2.97**

4. Press tours 150 3.62 150 3.77 -1.97*

5. Travels for a press club 150 2.31 150 2.98 -6.51**

6. Bargaining advertising 150 2.31 150 2.20 1.24

7. Exercising power through managers/editors of news bureaux 150 2.09 150 1.87 2.89**

8. Perks including dinner/drinking 150 3.06 150 3.40 -3.95**

9. Activities for friendship including golf/climbing 150 2.95 150 3.36 -4.65**

10. Presents and free tickets 150 2.75 150 3.16 -4.37**

11. Bribes 150 1.92 150 2.67 -7.60**

12. Overall mean 150 3.02 150 3.18 -3.65**

Note. ** p5 0.01, * p 5 0.05

Table 5: Comparison of journalists’ ethical values and journalists’ predictions of practitioners’ ethical values: ‘Congruency’ of journalists

Journalists’ Predictions of self-evaluations practitioners’ values

Items of informal relations N Mean N Mean t-value

1. Unofficial calls 150 4.47 150 4.00 -1.74

2. Private meetings 150 4.23 150 3.98 -4.41**

3. Regional/alumni/blood relations 150 3.78 150 3.36 -5.08**

4. Press tours 150 3.66 150 3.49 -2.00*

5. Travels for a press club 150 2.95 150 2.32 -6.64**

6. Bargaining advertising 150 2.75 150 1.78 -8.97**

7. Exercising power through managers/editors of news bureaux 150 2.75 150 1.68 -9.42**

8. Perks including dinner/drinking 150 3.26 150 2.60 -7.57**

9. Activities for friendship including golf/climbing 150 3.18 150 2.60 -6.64**

10. Presents and free tickets 150 2.94 150 2.07 -9.52**

11. Bribes 150 2.48 150 1.56 -9.42**

12. Overall mean 150 3.32 150 2.68 -9.74**

by-item comparisons of practitioners’ and journalists’ perceived ethical values of the other occupation and actual ethical values of the other are presented in Tables 6 and Table 7 respectively.

DISCUSSION

This study examined public relations practitioners’ and journalists’ perceptions and cross-perceptions regarding the influence of informal relations on the news and the ethical values of informal relations. A theoretical base exists to suggest that

projections of estimations of the other’s perceptions, ie coorientational analysis, are useful determinants to measure whether two groups are consensual or conflictual regarding given topics. Such coorientation measures have been found to be effective in explaining dimensions of pluralistic ignorance or false consensus,

overestimations or underestimations of the other.54,55

Accuracy can be produced and increased by communication. Greater dialogue about the actual agreement regarding the

Table 6: Comparison of practitioners’ predictions of journalists’ ethical values and the actual ethical values of journalists: ‘Accuracy’ of practitioners

Predictions of Journalists’ actual journalists’ values

values

Items of informal relations N Mean N Mean t-value

1. Unofficial calls 150 4.16 150 4.00 2.00*

2. Private meetings 150 4.10 150 3.98 1.42

3. Regional/alumni/blood relations 150 3.19 150 3.37 -1.60

4. Press tours 150 3.77 150 3.51 2.48*

5. Travels for a press club 150 2.97 150 2.33 5.52**

6. Bargaining advertising 150 2.20 150 1.79 3.68**

7. Exercising power through managers/editors of news bureaux 150 1.89 150 1.68 2.01*

8. Perks including dinner/drinking 150 3.40 150 2.61 7.42**

9. Activities for friendship including golf/climbing 150 3.36 150 2.61 6.97**

10. Presents and free tickets 150 3.15 150 2.10 10.05**

11. Bribes 150 2.67 150 1.58 10.06**

12. Overall mean 150 3.18 150 2.68 8.17**

Note. ** p5 0.01, * p 5 0.05

Table 7: Comparison of journalists’ predictions of practitioners’ ethical values and the actual ethical values of practitioners: ‘Accuracy’ of journalists

Predictions of Practitioners’ actual practitioners’ values

values

Items of informal relations N Mean N Mean t-value

1. Unofficial calls 150 4.48 150 4.45 -0.11

2. Private meetings 150 4.24 150 4.27 -0.39

3. Regional/alumni/blood relations 150 3.80 150 3.45 -3.04**

4. Press tours 150 3.65 150 3.62 -0.26

5. Travels for a press club 150 2.94 150 2.32 -5.29**

6. Bargaining advertising 150 2.76 150 2.33 -3.31**

7. Exercising power through managers/editors of news bureaux 150 2.75 150 2.09 -5.24**

8. Perks including dinner/drinking 150 3.24 150 3.06 -1.58

9. Activities for friendship including golf/climbing 150 2.18 150 2.96 -1.86

10. Presents and free tickets 150 2.95 150 2.75 -1.55

11. Bribes 150 2.48 150 1.92 -4.32**

12. Overall mean 150 3.32 150 3.02 -3.70**

Note. ** p5 0.01, * p 5 0.05

relations, particularly informal relations in the Korean and larger Asian context, might lead to greater understanding, enhance professional relationships between the two groups, improve beneficial social roles for source and reporter, and inform a more effective media relations practice for firms working in Asia, particularly those coming from a Western perspective. It is more important that practitioners understand journalists than vice versa. Practitioners, who require placement in print or on the air, depend on their

understanding of journalists rather than the converse. Nevertheless, practitioners in this study were not effective at predicting journalists’ perceptions in spite of having more at stake in the source–reporter relationship.

The first striking result is that practitioners and journalists disagree regarding the influence of informal relations on the news. Journalists do not perceive greater influence of informal relations on the news than practitioners. Conversely, practitioners perceive greater influence of informal relations on the news than journalists. It is possible that

journalists are reluctant to admit the power that informal relations play in the flow of information and possible

distortions of the news. This may account for journalists’ lower estimations of the influence of informal relations on the news. It is also possible that practitioners see their influence through informal relations as augmenting news content and coverage because they are comfortable with their self-serving motive for their advocacy role and hold a faith that their informal efforts have some notable effect on news content.56

Secondly, practitioners and journalists disagree overall regarding ethical values of informal relations other than the items of regional/alumni/blood relations and press tours, which implies that the items of informal relations originated from cultural

context and each profession’s need for informal relations can be ethically approved by both professions to some degree. Practitioners consider informal relations to be more ethical than do journalists, which may again be related to the practitioners’ self-serving motive and journalists’ fear of undue influence. Practitioners consider informal relations to be more ethical as well as perceiving a greater influence of informal relations on the news, which probably leads

practitioners to be more inclined to use informal relations to influence news content.

Interestingly, practitioners’ and journalists’ congruencies between their own perceptions and their predictions on the other party’s perceptions show difference regarding the ethical values of informal relations. Journalists perceive informal relations as more ethical

compared to their perceived ethical values of practitioners. Similarly, practitioners consider that journalists perceive informal relations as being more ethical in

comparison to their own ethical values. The perception gap of journalists is significantly bigger than that of

practitioners. It is possible that journalists ascribe ethical aspects of informal relations to themselves and realise their role as defenders of the public’s right to know. Practitioners, however, may rarely consider the journalistic concern. Practitioners may encounter fewer

dilemmas between their strategic values or need for informal relations, and ethical values or fear of informal relations than do journalists.

This study also found that practitioners’ and journalists’ predictions about the other group’s perceptions and the real

perceptions of the other differ significantly regarding the ethical values of informal relations. Practitioners predict that journalists perceive informal relations as more ethical. Journalists, however, predict

that practitioners perceive informal relations as more ethical. The prediction gap of practitioners is significantly bigger than that of journalists. This may account for the bigger misperceptions of

practitioners and indicate greater need for improving practitioners’ understanding of journalists.

The findings here generally reinforce the previous research that the two groups are misperceiving each other. First, however, this study deals with informal relations unique in the Korean context, where information flows and influences on the news are said to occur in an informal way. Journalists in Korea may perceive informal relations, which are involved in the unique press club system as important for news gathering. Journalists are likely to gather news information through the press club system, with its restricted and controlled membership in Korea, similar to the systems in other Asian countries. This system explicitly shows the personal influence and cultural difference in public relations and media relations.57–59

Secondly, both aspects of the influence on the news and related ethical values are considered in this study. The

misunderstanding between practitioners and journalists are related mostly to their inherent source and reporter relationship and partly to public relations practices. Informal relations obviously indicate a core matter of the discord or consensus between the two professions along the two dimensions studied here: impacts and ethics.

While, as presented, there are inherent conflicts between practitioners and journalists in source and reporter

relationship, and certainly some degree of inevitable tension is healthy, there is at least a need to recognise that both professions understand the other’s role. Similar perceptions of informal relations might benefit both professional groups and also serve beneficial social roles.

Practitioner understanding of journalists is needed more because it helps practitioners get out of the dilemma between strategic values and ethical values, and play a constructive source role. Practitioners need to understand the conflictual or

cooperative components in the relationship with journalists, particularly in informal relations in Korean context. Their ethical codes are likely to be attuned to

interpersonal interactions in an informal way to some degree. Some informal relations are ethically accepted to meet the needs of both professions and help

construct their social roles.

The relationship between practitioners and journalists is a communicative process interacting with external factors such as culture, norms, customs, values,

organisations and society. There still remains an important place for

‘interpersonal’ factors originating from the Korean culture in public relations

practices, and some informal relations are culturally appropriate in the Korean communication context. This calls for further development of a pan-Asian public relations model built upon personal influence, which cannot be identified with the normative model in the USA. In the personal influence model, the interpersonal and informal relationship between

journalists and public relations practitioners plays an important role in their news gathering or dissemination process.

Overall, this study suggests some practical implications by incorporating the cultural aspects of the source–reporter relationship. The press club systems create social networking, which influences the news dissemination or gathering process with informal or unofficial communication beyond official news releases or formal interviews. Journalists in Korea mostly depend on informational resources from public relations practitioners through the institutionalised human network. They enjoy the implicit context of informal

relations to get a unique scoop from informally communicated messages. Public relations practitioners also appreciate the convenience of disseminating news through the press club system. They often provide background information through word of mouth in the interpersonal relationship. Their informational exchange generally occurs in informal settings, such as informal meetings over dinner or drinks, activities for friendship including golf/climbing etc.

Since relational or social orientation through the press club system is critical in SE Asian media relations, public relations practitioners who plan to design and implement media relations practice in Korea and elsewhere in SE Asia need to understand informal relations with

journalists as influential and ethical in their news disseminating or gathering process to some degree. They also should be

accustomed to the patterns for interacting with journalists in the media systems. References

1. Westley, B. H. and MacLean M. S. (1957) ‘A conceptual model of communications research’, Journalism Quarterly, Vol. 34, No. 1, pp. 31–38. 2. Giber, W. and Johnson, W. (1961) ‘The city hall beat:

A study of reporter and source roles’, Journalism Quarterly, Vol. 38, No. 2, pp. 289–297.

3. Cutlip, S. M., Center, A. H. and Broom, G. M. (1994) ‘Effective public relations’, 7th ed., Prentice-Hall, Inc., Englewood Cliffs, NJ.

4. Cameron, G. T., Sallot, L. M. and Curtin, P. A. (1997) ‘Public relations and the production of news: Critical review and theoretical framework’, Communication Year Book, Vol. 20, pp. 111–115. 5. Gandy, O. H., Jr. (1982) ‘Beyond agenda setting:

Information subsidies and public policy’, Ablex, Norwood, NJ.

6. Schoemaker, P. and Reese, S. (1991) ‘Mediating the messages: Theories of influence on mass media content’, Longman, New York.

7. Berkowitz, D. (1993) ‘Work rules and news selection in local TV: Examining the business-journalism dialectic’, Journal of Broadcasting and Electronic Media, Vol. 37, pp. 67–81.

8. Cutlip, S. M. (1962) ‘The third of newspapers’ content PR-inspired’, Editor & Publisher, Vol. 26, p. 68. 9. Schabacker, W. (1963) ‘Public relations and the news

media: A study of the relation and utilization of representative Milwaukee news media of materials

emanating from public relations sources’, unpublished master’s thesis, University of Wisconsin.

10. Aronoff, C. E. (1976) ‘Predictors of success in placing news releases in newspapers’, Public Relations Review, Vol. 2, No. 4, pp. 43–57.

11. Curtin, P. A. and Rhodenbough, E. (2001) ‘Building the news media agenda on the environment: A comparison of public relations and journalistic sources’, Public Relations Review, Vol. 27, No. 2, pp. 179–190.

12. Lee, M. A. and Solomon, N. (1990) ‘Unreliable Sources’, Carol, New York.

13. Sachsman, D. B. (1976) ‘Public relations influence on coverage of environment in San Francisco area’, Journalism Quarterly, Vol. 53, No. 1, pp. 54–60. 14. Sallot, L. M. (1990) ‘Public relations and mass media:

How professionals in the fields in Miami and New York view public relations effects on the mass media, themselves, and each other’, paper presented at the annual meeting of the Association for Education in Journalism and Mass Communication, Minneapolis. 15. Baxter, B. L. (1981) ‘The news release: An idea whose

time has gone?’, Public Relations Review, Vol. 7, No. 1, pp. 27–31.

16. Turk, J. V. (1985) ‘Information subsidies and influence’, Public Relations Review, Vol. 11, No. 3, pp. 10–25.

17. Cameron et al. (1997) op. cit.

18. Kim, I. C. (1973) ‘Communication systems in Korean society’, Chunyaewon, Seoul.

19. Gang, M. G. (1991) ‘Practices of a press club in Korea’, Journalism Review, Vol. 6, pp. 30–41. 20. Kang, J. M. (1991) ‘Control systems of the press in

Korea’, Nare, Seoul.

21. Shin, H. C. (1994) ‘A thought of media relations in Korean corporations’, Journal of Korean Advertising Research, Vol. 23, pp. 142–145.

22. Kim (1973) op. cit. 23. Gang (1991) op. cit. 24. Kang (1991) op. cit. 25. Shin (1994) op. cit. 26. Cameron et al. (1997) op. cit.

27. Aronoff, C. E. (1975) ‘Credibility of public relations for journalists’, Public Relations Review, Vol. 1, No. 1, pp. 45–56.

28. Jeffers, D. W. (1977) ‘Performance expectations as a measure of relative status of news and PR people’, Journalism Quarterly, Vol. 54, No. 2, pp. 299–306. 29. Belz, A., Talbott, A. D. and Starck, K. (1989) ‘Using

role theory to study cross perceptions of journalists and public relations practitioners, in Grunig, J. E. and Grunig, L. A. (eds) ‘Public Relations Research Annual’, Vol. 1, pp. 125–139.

30. Ryan, M. and Martinson, D. L. (1984) ‘Ethical values, the flow of journalistic information and public relations persons’, Journalism Quarterly, Vol. 61, No. 1, pp. 27–34.

31. Kopenhaver, L. L. (1985) ‘Aligning values of practitioners and journalists’, Public Relations Review, Vol. 11, No. 2, pp. 34–42.

32. Stegall, S. K. and Sanders, K. P. (1986) ‘Co-orientation of PR practitioners and news personnel in

education news’, Journalism Quarterly, Vol. 63, No. 2, pp. 341–347.

33. Swartz, J. E. (1983) ‘On the margin: Between journalist and publicist’, Public Relations Review, Vol. 9, No. 3, pp. 11–23.

34. Brody, E. W. (1984) ‘Antipathy exaggerated between journalism and public relations’, Public Relations Review, Vol. 10, No. 4, pp. 11–15.

35. Sallot, L. M., Steinfatt, T. M. and Salwen, M. B. (1998) ‘Journalists’ and public relations practitioners’ news values: Perceptions and cross-perceptions’, Journalism and Mass Communication Quarterly, Vol. 75, No. 2, pp. 366–377.

36. Cline, C. (1982) ‘The image of public relations in mass communication texts’, Public Relations Review, Vol. 8, No. 3, pp. 63–72.

37. Turk, J. V. (1988) ‘Public relations’ influence on the news’, in Hiebert, R. E. (ed.) ‘Precision public relations’, New York: Longman, pp. 224–239. 38. Pincus, J. D., Rimmer, T., Rayfield, R. E. and

Cropp, F. (1993) ‘Newspaper editors’ perceptions of public relations: How business, news and sports editors differ’, Journal of Public Relations Research, Vol. 5, No. 1, pp. 27–45.

39. Ryan, M. and Martinson, D. L. (1988) ‘Journalists and public relations practitioners: Why the antagonism?’, Journalism Quarterly, Vol. 65, No. 1, pp. 131–140. 40. Ryan, M. and Martinson, D. L. (1991) ‘How

journalists and public relations practitioners define lying’, paper presented at the annual meeting of the Association for Education in Journalism and Mass Communication, Boston.

41. Spicer, C. H. (1993) ‘Images of public relations in the print media’, Journal of Public Relations Research, Vol. 5, No. 1, pp. 47–61.

42. Pratt, C. B. (1991) ‘An empirical research on practitioner ethics’, Journal of Business Ethics, Vol. 10, pp. 229–236.

43. Saunders, M. D. (1989) ‘Ethical dilemmas in public relations: Perceptions of Florida practitioners’, Florida Communication Journal, Vol. 17, No. 2, pp. 23–27. 44. Pearson, R. (1989) ‘Beyond ethical relativism in public

relations: Co-orientation, rules, and the idea of communication symmetry’, in Grunig, L. A. and Grunig, J. E. (eds) ‘Pubic Relations Research Annual’,

Vol. 1, pp. 67–87.

45. Cameron, G. T. (1997) ‘The contingency theory of conflict management in public relations’, proceedings of the Norwegian Information Service, Oslo, Norway.

46. Cameron, G. T., Cropp, F. and Reber, B. H. (2001) ‘Getting past platitudes: Factors limiting

accommodation in public relations’, Journal of Communication Management, Vol. 5, No. 3, pp. 242– 261.

47. Cancel, A. E., Cameron, G. T., Sallot, L. M. and Mitrook, M. A. (1997) ‘It depends: A contingency theory of accommodation in public relations’, Journal of Public Relations Research, Vol. 9, No. 1, pp. 31–63. 48. Cancel, A. E., Mitrook, M. A. and Cameron, G. T.

(1999) ‘Testing the contingency theory of accommodation in public relations’, Public Relations Review, Vol. 25, No. 2, pp. 171–197.

49. Sriramesh, K. (1992) ‘Social culture and public relations: Ethnographic evidence from India’, Public Relations Review, Vol. 18, No. 2, pp. 201–212. 50. Sriramesh, K., Kim, Y. W. and Takasaki, M. (1999)

‘Public relations in three Asian cultures: an analysis’, Journal of Public Relations Research, Vol. 11, No. 4, pp. 271–292.

51. Sriramesh, K. and Takasaki, M. (1998) ‘The impact of culture on Japanese public relations’, Journal of Communication Management, Vol. 3, No. 4, pp. 337–352. 52. Shin, J. H. and Cameron, G. T. (2002) ‘A

cross-cultural view of conflict in media relations: The conflict management typology of media relations in Korea and in the U.S.’, paper submitted at the annual meeting of the Association for Education in Journalism and Mass Communication, Miami, p. 4.

53. Ibid., p. 9.

54. McLeod, J. M. and Chaffee, S. H. (1973) ‘Interpersonal approaches to communication research’, American Behavioral Scientist, Vol. 16, pp. 469–99.

55. Newcomb, T. M. (1953) ‘An approach to the study of communicative arts’, Psychological Review, Vol. 60, pp. 393–404.

56. Cameron et al. (1997) op. cit. 57. Sriramesh (1992) op. cit. 58. Sriramesh et al. (1998) op. cit. 59. Sriramesh et al. (1999) op. cit.

웹페이지와 트위터 메시지에 나타난

이미지 회복 전략 비교연구:

제주 해군기지 건설 사례를 중심으로

남성주*1) 부산대 신문방송학과 석사과정 황성욱**2) 부산대 신문방송학과 부교수 이 연구는 제주 해군기지 건설을 둘러싸고 발생한 위기상황에서 해군이 사용한 이미지 회복 전략을 베노이트의 이론을 적용하여 내용 분석을 실시한 것이다. 특히 웹페이지와 트위터라는 매체적 특성이 이미지 회복 전략에 어떠한 차이를 나타내는지 살펴보았다. 트위터와 웹페이지의 메시지를 비교 분석한 결과 해군은 공식 웹페이지를 통해 부인전 략, 책임성의 회피와 같은 조직옹호적 전략 그리고 공격성의 감소 전략을 주로 이용했으 며 트위터에서는 공격성의 감소 전략을 주로 사용해 상대적으로 웹페이지에 비해 공중 에 순응적인 전략을 나타내는 차이점을 관찰했다. 소구유형에서도 웹페이지는 이성적 소구를 주로 사용한 반면 트위터는 감성적 소구에 주로 의존하는 차이를 나타냈다. 이미 지 회복 전략별 소구유형을 살펴보면 두 매체 모두 대체적으로 각 이미지 회복 전략별로 감성보다 이성적 소구를 선호했으나 트위터의 경우 공격성의 감소 전략을 사용할 때 상 대적으로 이성보다 감성적 소구를 더 많이 이용했다. 이러한 연구 결과는 매체의 유형과 성격에 따라 적합한 이미지 회복 전략과 소구유형이 다를 수 있으므로 매체의 유형에 맞 는 차별화된 위기 커뮤니케이션 메시지 전략이 필요함을 암시하였다. ▪주제어: 이미지 회복 전략, 위기관리, 해군기지, 트위터, 웹페이지, 소구 유형, 내용 분석 * smartsom@nate.com ** hsw110@pusan.ac.kr, 교신저자6 _방송과 커뮤니케이션 2013년 제14권 2호

1. 문제 제기

현대 사회에 많은 조직은 다양한 이해관계자와 특정 이슈에 직면하여 상이

한 공중관계를 형성한다

. 이슈는 위험으로 발전하고, 위험은 다시 공중에

인지되어 위기로 부각되며 많은 다양한 조직은 조직을 둘러싼 위기를 어떻게

효율적으로 극복할 것인지에 대해 현실적이고 전략적인 고민을 한다

. 학계에

서도 조직의 위기관리와 관련해 그동안 무수하게 많은 연구들이 진행되어

왔다

. 특히 조직의 위기관리에서 어떤 반응적 메시지 전략을 이용했는지

어떻게 메시지 전략을 사용하는 것이 바람직한지 등의 유관주제는 위기관리

연구의 중요한 한 영역을 차지하였다

(Ham, Hwang, & Cameron, 2011).

위기관리 커뮤니케이션에서 동시대의 매체 환경에 대해 많은 사람은 그것

이 매우 복잡다단하여 재앙적인 환경이 아닌가 염려하기도 한다

. 즉, 많은

매체의 출현과 사용의 폭발적인 증가로 인해

PR실무자가 고려해야 할 채널이

증가하였기 때문이다

. 그러나 쌍방향 커뮤니케이션과 메시지 전달의 즉시성

이 극대화된 매체 환경을 전략적으로 활용할 경우 오히려 좀 더 긍정적인

소통과 반향을 불러일으킬 수 있다는 전환적인 평가와 기대도 상존한다

.

주지하다시피 기존의 많은 위기관리 메시지 전략 연구들

(김영욱, 2006b;

김영욱

·박송희·오현정, 2002; 나재훈·윤영민, 2008; 이철한, 2007)은 하나의

조직

, 하나의 사례, 동일 유형의 매체라는 틀 속에서 어떤 위기 극복 메시지

전략들이 조직에 의해 채택

, 전달되어졌는가를 분석하는 데 많은 노력을

경주하였다

. 이러한 연구들이 다양한 조직과 사례들을 통해 마치 데이터베이

스화되듯이 축적되는 것은 좀 더 실용적이고 바람직한 위기 커뮤니케이션

메시지 전략에 대한 논의를 풍성하게 한다는 점에서 분명한 의미가 있으나

계속해서 단편적인 시각에 머무른다는 점에서는 다소 한계가 있다고 볼 수

있다

.

이 점을 염두에 두면서 이 연구는 서로 다른 매체 간의 차이와 특성에

따라 조직이 적절히 이용할 수 있는 위기극복 메시지 전략도 상이하지 않을까

하는 의문점에서 출발하였다

. 마샬 맥루한(Marshall McLuhan)이 ‘미디어는

메시지다

’라는 말로 매체에 따라 메시지가 달라진다고 주장했듯이 갈등적

상황을 해결하기 위해서는 메시지 자체도 중요하지만 매체의 특성을 이해하

고 그에 맞는 메시지 유형을 게재 및 전송하는 것도 매우 중요하기 때문이다

.

위기관리 메시지 전략 내용 분석 연구의 흐름을 이해하고 소셜미디어로

진화한 동시대의 온라인 매체 환경을 인지하면서 이 연구는 조직이 기존의

대표적인 온라인 매체인 웹페이지와 쌍방향 커뮤니케이션이 극대화된

SNS매

체상에서 위기극복 메시지 전략 및 메시지 소구유형을 사용하는 데 어떠한

차이점을 보여주는지 조사하고자 한다

. 이를 통해 관찰되는 차이점을 매체의

특성에 비추어 해석하며 바람직한 위기 극복 메시지 전략의 매체별 방향을

진단하고 제시하는 데 그 목적을 둔다

.

그 연구 목적에 적합한 사례를 선정하기 위해 이 연구는 다음의 세 가지를

고려하였다

. 즉, 이 연구가 매체의 특성에 따른 위기 커뮤니케이션의 차이를

본다는 점

, 웹사이트와 트위터를 함께 이용하는 비교적 최근의 위기 커뮤니케

이션을 조명한다는 점

, 그리고 많은 공중이 인지하는 노출도 높은 조직 위기

관리 사례를 주목한다는 점이다

. 상기 조건을 동시에 만족시키는 최근 사례로

서 이 연구는 널리 알려진 행정조직의 갈등 사례인 제주 해군기지 건설 관련

위기 커뮤니케이션 사례를 주목하고 이를 분석하였다

.

기존의 이미지 회복 이론연구들이 간과한 다매체를 통한 위기 커뮤니케이

션을 주목하고 또한 이미지 회복 전략 유형만이 아닌 광고학 분야에서 소구전

략으로 주로 연구되어 온 이성적

·감성적 소구를 함께 분석함으로써 이 연구

는 기존 연구들의 이미지 회복 전략 중심의 단면적 해석에서 나아가 웹사이트

와 트위터상에서의 광고학 분야 및

PR학 분야의 주요 메시지 전략 간의

관계성이라는 입체적인 지식을 새롭게 보탠다

. 이러한 점에서 본 연구의

중요성을 찾아볼 수 있다

.

8 _방송과 커뮤니케이션 2013년 제14권 2호

2. 문헌연구

이 연구의 문헌연구는 다음과 같은 세부 주제로 구성된다

. 먼저, 조직의

온라인

PR커뮤니케이션 연구들을 웹페이지와 트위터 위주로 정리하고자 한

다

. 다음으로 이 연구의 중심 이론인 베노이트의 이미지 회복 전략과 관련한

연구들을 요약한다

. 또한 이미지 회복 전략의 메시지 유형과 더불어 이 연구

가 주목하는 메시지 소구유형인 이성적 소구와 감성적 소구에 대한 기존의

논의를 살펴보고 연구자들이 사례로 선정한 제주해군기지 관련 위기사례의

맥락을 요약하여 독자의 이해를 돕고자 한다

.

1) 온라인을 통한 조직의 PR커뮤니케이션

다양한 온라인 매체의 등장으로 조직

PR을 위해 PR실무자가 관리해야 할

영역이 확장되었다

. 과거의 PR은 신문, 방송과 같은 전통매체에 대한 접근과

활용에 초점이 맞추어져 있었다면

, 오늘날에는 조직 스스로가 공중을 상대로

직접적인 커뮤니케이션을 수행하는 환경이 조성되었기 때문에 전통매체 만

큼이나 온라인

PR활동의 중요성 역시 강조되고 있다(배미경, 2003).

(1) 웹페이지PR웹페이지는 인터넷의 등장과 함께 조직이 가장 일반적으로 사용하는 커뮤

니케이션 수단이다

. 인터넷을 통한 시간과 공간의 확장은 조직의 온라인PR

도구로서 웹페이지가 자사에 대한 정보와 입장을 공중에게 효과적으로 전달

하고

, 조직이나 제품에 대한 긍정적 태도를 유도하며, 공중과의 우호적인

관계를 형성하는 중요한 도구가 될 수 있음을 의미한다

(홍종필, 2006).

기존의 전통매체와 비교하여 인터넷 웹페이지가 갖는 장점을 양성관

·이현

우

·김형석(2002)은 크게 여섯 가지로 분류하였다. 첫 번째는 정보의 여과

과정

(gate-keeping)을 거치지 않기 때문에 조직이 원하는 정보를 직접적으로

제공할 수 있다는 점이다

. 전통매체는 편집자를 거쳐 메시지가 통제됨으로

인해 조직의 입장에서 반드시 유리한 정보만 유통되는 것은 아니었다

. 따라서

조직이 정보의 제공자이자 유통자가 된다는 것은 수용자에게 의도한 효과를

발휘하는 데 긍정적으로 작용할 수 있을 것이다

. 두 번째는 상호작용성의

강화이다

. 인터넷 게시판을 통해 이용자의 불만이나 문의사항을 즉각적으로

대응할 수 있기 때문에 커뮤니케이션의 효율성이 증대된다고 볼 수 있다

.

세 번째로는 이용자에 대한 분석이다

. 인터넷은 이용자들의 정확한 분석을

통해 커뮤니케이션 경로나 이용 동기 등을 파악하기 유리하다

. 따라서 이용자

개개인 맞춤형 정보 제공이 가능해진다

. 네 번째로는 시간과 공간의 확장성을

들 수 있다

. 인터넷을 통해 언제 어디서나 접속이 가능하기 때문에 특정

시간이나 공간에 구애받지 않고 접속할 수 있다

. 다섯 번째로는 자료의 업데

이트가 쉽다는 점이다

. 자료의 신속한 업데이트와 정보의 수정 및 보완은

상황에 맞는 정보를 지속적으로 제공할 수 있게 한다

. 마지막으로 정보 중심

의 메시지 제공이 가능하다는 점인데 자발적이고 능동적인 인터넷 이용자들

에게 정보를 제공함으로써 합리적이고 이성적인 의사결정을 하는 데 적합하

다는 장점이 있다

(양성관·이현우·김형석, 2002).

이상경과 성민정

(2010)의 연구도 공중이 온라인 커뮤니티와 기업 웹페이

지에 대해 긍정적인 태도를 형성하고 있음을 밝혀 조직

PR커뮤니케이션에

있어서 웹페이지의 장점을 재강조하였다

. 특히 웹페이지는 메시지를 통제하

기 힘든 온라인 커뮤니티 다음으로 이용자의 신뢰도와 호감도 형성에 긍정적

역할을 하는 것으로 나타났다

. 따라서 조직은 신뢰도 및 제품 구매 의도를

높이기 위해 온라인 매체를 적절히 활용하는 것이 권장된다

. 또한 웹페이지에

전달되는 정보들을 통해 공중은 조직에 대한 만족도를 높이며

, 조직은 공중과

의 돈독한 관계를 형성하고 유지하며 지속적으로 커뮤니케이션할 수 있는

기반을 마련한다

(안대천·김상훈, 2008)라는 점에서 그 순기능을 찾아볼 수

10 _방송과 커뮤니케이션 2013년 제14권 2호